Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) play a key role in a country’s GDP growth. However, several factors obstruct their access to formal financial services. This video highlights how start-ups under the FI lab have been trying to solve these challenges through alternate data sources and technology, and democratizing finance for the MSME segment.

Bridge2Capital: Breaking the patterns of the erstwhile normal

This blog looks at Bridge2Capital, a startup that was part of the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which receives support from some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world—Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

The journey so far

Back in 2017, Bridge2Capital began with a simple idea—to provide working capital support to retail merchants in India, including local mom-and-pop stores called kiranas in a timely and easy manner. Our earlier blog narrated Bridge2Capital’s journey as it adopted an uncommon, yet robust, strategy of Goods and Service Tax (GST) based invoice discounting. Instead of paying to its borrower, Bridge2Capital directly paid to the supplier to ensure the end-use of funds. Under this process, retailers got timely access to working capital to run and grow their businesses and serve more customers. As retailers earn over a period, they pay back the capital in evenly distributed installments over a few weeks or months.

Bridge2Capital has on-boarded more than 1,200 shopkeepers on its digital platform till now. The startup has grown its network from about 300 retailers in 3-4 cities when it joined us in the first and second cohort to explore new geographies and increase its footprint. Bridge2Capital has now started to increase its digital footprint and enhance the overall business of shopkeepers by adding various new products.

How did COVID-19 change Bridge2capital’s strategy?

The government imposed nationwide lockdowns in March, 2020 to flatten the curve of infection and prepare the country to handle the crisis of COVID-19. The pandemic slowed down the economy and brought financial hardships for kirana retailers. Curfews and the strict lockdown had a severe impact on the livelihood of retailers who borrowed from Bridge2Capital.

To provide relief to these retailers, RBI announced a moratorium on loan repayments. Many borrowers of Bridge2Capital found it difficult to pay back their installments and opted for the moratorium. Yet unlike many other startups that succumbed to the pressures of the pandemic, Bridge2Capital found an opportunity in the adverse time to re-think, re-plan, and re-emerge with a holistic strategy. It focused on three key pillars to redefine and adapt its business to a new normal.

- Human capital: Despite tough times, the management did not lay off a single team member. Instead, it found ways to keep them employed gainfully. With the focus on customer care, Bridge2Capital redefined the KRAs of its staff. It cross-skilled its staff to play multiple roles, based on ever-evolving needs during the pandemic and encouraged and supported them to further the company’s vision.

- Product development: With changing needs of their customers in these times, Bridge2Capital realized the opportunity to introduce relevant products. As the pandemic struck, the demand for savings and insurance products shot up due to the prevailing uncertainty, and the resultant risk to health and future earnings.

Using a human-centered design approach, Bridge2Capital has been building a full-stack financial solution for its shopkeepers that supports their varied financial needs. To arrive at the right solution, the startup interviewed existing and potential customers and brainstormed with the frontline sales team that deals with retailers, UI/UX specialists, and tech teams.

Based on these discussions, Bridge2Capital worked on solutions, such as gold-based savings, digital insurance products, and pension services for its existing network of shopkeepers to build their financial well-being. The startup also introduced a digital ledger to help its shopkeeper borrowers to manage their finances easily. This feature helps the borrowers engage more with customers and also generates additional data sets for the company.

3. Digital expansion: As COVID-19 restricted the scope to reach customers physically, Bridge2Capital decided to go fully digital. With a focus on digital marketing, the startup hired skilled resources—even in these difficult times—to set up a plan to grow the business.

Before the pandemic, the process of financing invoices was fully digital, but on-boarding and customer support were highly human-centric and manual processes. Bridge2Capital changed some of those manual processes like replacing physical- with remote- (video) KYC, moving from physical support to onboarding customers with telephone-assisted processes, among others.

To spruce up its digital communication, the startup focused on targeted social media campaigns for brand building, customer acquisition, and cross-selling. These efforts paid off and helped Bridge2Capital expand rapidly while reducing the costs of customer acquisition.

The FI Lab supported Bridge2Capital in building a holistic strategy

- As the pandemic was making everyone learn new skills and new ways to work, the Lab also used remote assistance tools to help Bridge2Capital to create a structured plan to fulfill its objectives. The Lab ran a customized strategic business planning (SBP) workshop for founders and senior team members. This helped condense their ideas by understanding the competition, building on their objectives, and thus prioritizing the company’s goals and resources for the next three years. The SBP also helped the management analyze strengths and weaknesses and build agility in business operations.

- Considering the constraints imposed by the pandemic, the Lab worked with Bridge2Capital to create a digital marketing roadmap to engage various stakeholders. This included assistance to create brand awareness, loyalty programs, and digital on-boarding for customers. In particular, the Lab helped Bridge2Capital to focus its marketing efforts on the targeted low-middle-income (LMI) sub-segment of kirana store owners. With its nuanced approach, the roadmap created an impactful market strategy to increase conversions, build trust, and enhance Bridge2Capital’s brand value for this sub-segment and provide a strong mechanism to resolve grievances to refine the overall experience of its customers.

Way forward: The future is digital

COVID-19 has triggered a complete digital transformation. Accordingly, Bridge2Capital will focus on going 100% digital in the next six months. Goal-based campaigns, referral bonuses, and influencer marketing will continue to drive conversion and engagement. For effective outreach, the startup will focus on understanding the needs, habits, preferences, and behavioral triggers of the customer segment. The insights will help deliver relevant products and create effective communication and strengthen customer relationships.

Bridge2Capital has also been in talks with leading organizations for strategic partnerships. It also intends to continually explore new geographies as it goes 100% digital, to create a nationwide presence. While Bridge2Capital improves its business and marketing strategy, it will continue to focus on strengthening the financial profile of small shopkeepers and their empowerment through unique financial solutions that suit their needs.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that have been making a difference to underserved communities. These startups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat

Credochain: Lending solutions for a new India

This blog is about a startup under the Financial Inclusion (FI) Lab accelerator program’s third and fourth cohorts, which receive support from some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world—the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

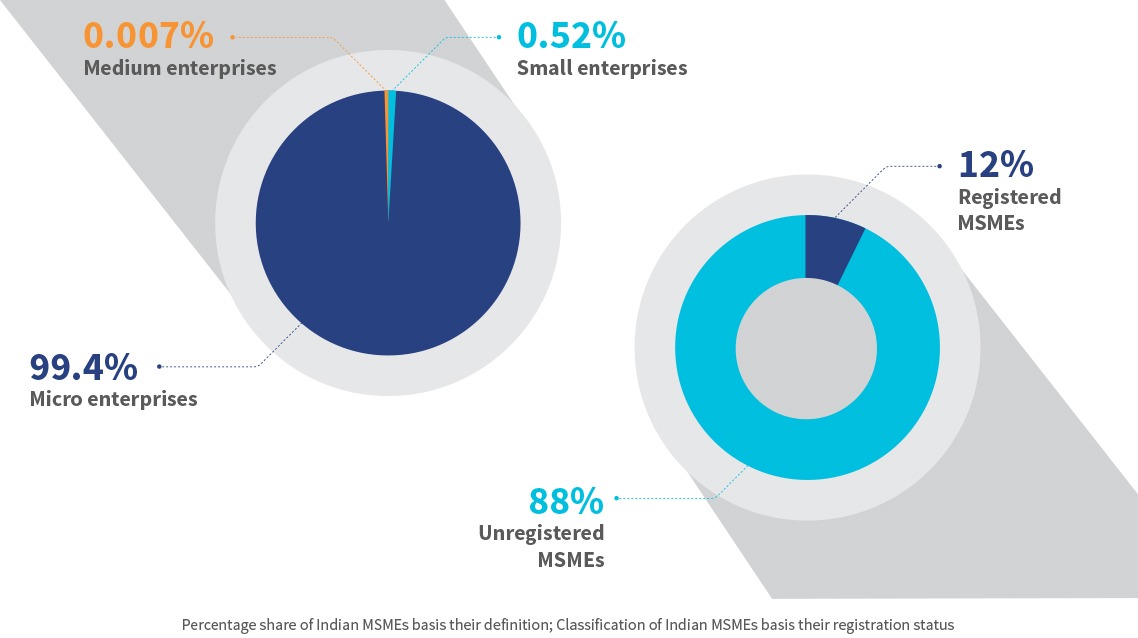

According to the latest report from the Government of India’s MSME Ministry, the MSME sector comprises 63.8 million units, of which 99.4% are micro-enterprises. However, only 9 million of these are formally registered.

Banks find it difficult to underwrite loans to MSMEs since 88% of them are unregistered and lack reliable financial footprints. The MSMEs that can provide some collaterals and supportive documents, approach non-banking financial companies (NBFC), whose rate of interest is 5%-8% more than what banks offer. The rest of the MSMEs are compelled to pursue other sources and generally end up taking loans from informal sources, such as moneylenders, who exploit them.

During the nationwide lockdowns due to the COVID-19 outbreak in India, MSMEs curtailed their production activities and their revenues suffered. To support this segment, the Government of India launched several initiatives, such as the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS) for unsecured lending, a relief package worth USD 60.4 billion, and other loan waiver or moratorium programs. However, several studies showed that most MSMEs are unaware of these programs and those who approach lenders to inquire about these schemes face heavy scrutiny from lenders. Since 2020, lenders have become risk-averse. Now, the quality and proper documentation of portfolios are of utmost priority to prevent credit defaults. While non-performing assets (NPAs) for most lenders are under control, for now, RBI predicts an increase in the gross NPA ratio for the rest of the financial year.

These factors have created a significant gap in the market and an opportunity for new-age FinTech lenders. One such startup is Credochain, which uses alternative data and proxies to support underserved businesses. It extends its application programming interfaces (APIs) to commercial banks, which in turn leverage it to offer relevant products and services to the underserved MSMEs. Credochain seeks to add value to the Indian business ecosystem by serving micro and nano enterprises with addressable credit requirements.

a) The light-bulb moment

Vaibhav Anand conceived the idea of Credochain while working as a consultant in the FinTech vertical for Deloitte, India. During his stint there, he realized that more than 80% of Indian small businesses sought working capital support but incumbent financial institutions denied them. He felt that since small businesses largely lack proper documentation and credit history, lenders either deny loans or at best offer smaller loan amounts. This gap in credit supply held immense opportunities for FinTechs that can facilitate credit to non-formal and semi-formal businesses. Credochain’s vision was strengthened further when Vaibhav’s wife Shivani Sharma, an ex-private equity professional, joined hands to pursue this opportunity.

They initially started with the idea of analyzing e-way bills to shape a credit facilitation business model but it did not gain much traction in the market. After some rethinking, pivoting, and effort, the two finally zeroed in on a unique business problem to solve—cluster-based lending to small enterprises.

India accounts for around 20 million manufacturing MSMEs spread across 5,500 clusters. Several traditional institutions have tried to underwrite credit to the cluster-based businesses but failed, mainly due to the absence of credible data of these clusters. Generally, MSMEs fail to adequately document information around inventory cycle, payments, lending, borrowing, and bookkeeping. This makes it difficult for potential lenders to establish the worth of the business and its ability to repay. To solve the issue of assessing creditworthiness, Credochain has worked to build cluster-specific credit underwriting APIs.

b) The unique pitch

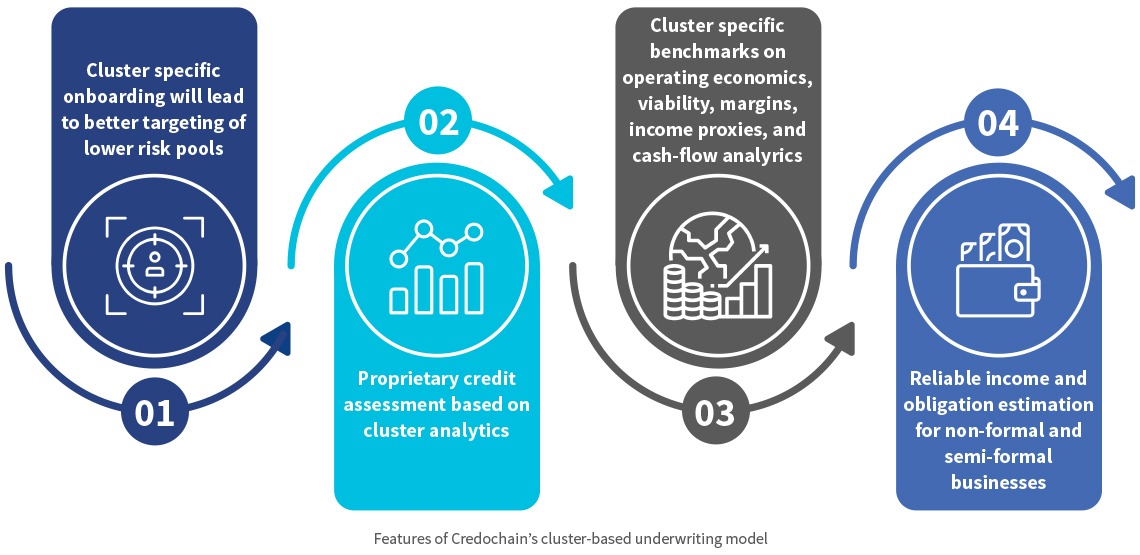

Credochain is committed to building market linkages between commercial lenders and semi-formal and non-formal enterprises that lack proper documentation. Credochain intends to analyze the cluster businesses at the atomic level by taking each cluster independently. They understand that a “one-size-fits-all” assessment model cannot cater to the different clusters or geographies in India. Hence Credochain built a customized assessment approach for each cluster depending on the cluster business.

Credochain follows a top-down approach to generate alternative cluster-specific data to shortlist semi-formal and non-formal businesses and build low-risk lending pipelines for commercial lenders. It uses cash-flow data, inventory data, bill of materials, and operating economics, among other possible proxies at a granular level to identify the business potential of these enterprises. To collect these data points, it relies on a “phygital” (combination of physical and digital) model, where a business is onboarded via assisted digital modes but is validated physically—by a Credochain officer who visits the business as a part of the follow-up process. Credochain will tweak this model and optimize it to assess semi-formal and non-formal businesses in different clusters and digitalize the processes to the extent possible.

c) Impact on LMI segments

In 2021, Credochain onboarded 600+ micro-businesses on its platform for loan pre-qualification and is set to disburse INR 5 crore (USD 684K) later in the year. Extending working capital at the right time can help businesses address their operational needs and manage their finances better, pay laborers on time, and grow sustainably. In the long run, this will help improve the lives of all the LMI families that are associated with these businesses.

d) COVID-19 along with several ecosystem-related roadblocks made the path ahead seem much longer

Cluster analysis is cumbersome as it requires extensive on-field analysis to understand the cluster map. Accordingly, Credochain aligned its model to physically assess business inventory and capture its production capabilities and other relevant indicators, before assigning a credit-like assessment score to the business. Due to the pandemic, Credochain’s physical operations and assessments were delayed significantly and it was forced to carry most of its assessment digitally.

Credochain initially ran into difficulties as it tried to establish business relationships with commercial lenders—even those with a successful model. Closing business-to-business (B2B) deals in the FinTech ecosystem is a challenging and time-consuming process. Moreover, considering the pandemic situation, commercial lenders have been more risk-averse in lending to prevent loan impairments. This limits Credochain’s focus to data-rich prospects.

Despite these challenges, Credochain has onboarded a few banks on its platform and has also been in active discussions to partner with more lenders.

e) Support provided by the Financial Inclusion (FI) Lab

In collaboration with MSC, CIIE.CO organized boot camps, diagnostic sessions, mentoring support, and technical assistance (TA) to build robust strategies and identify the challenges for Credochain. We also carried out a competitor analysis for Credochain against other digital lenders to enhance its operational model, identify gaps in solutions provided in the market today, and recommend implementable strategies.

MSC developed cluster maps for the Agra and Ludhiana-based clusters that are into footwear, hosiery, and cloth manufacturing. The analysis helped Credochain identify its target segments, gauge the addressable market size, and build a sustainable business model. We also designed a credit assessment framework that can use the bill-of-materials data of non-formal and semi-formal businesses, among other inputs. It enabled Credochain to focus on businesses that lack proper documentation and records to support their revenue statements. The tool helps scale up Credochain’s business model.

The way forward

Credochain intends to onboard 28,000+ semi-formal and non-formal businesses spread across different manufacturing clusters in Ludhiana, Jaipur, and Agra while also looking to expand to a few clusters across Panipat. Credochain’s vision is to originate INR 50 crore (USD 7 million) by 2022 and help small enterprises build their businesses based on a lower cost of capital.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that are making a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll #BuildingForBharat

Fundfina: A journey to tap a hidden multi-million MSME market in India

This blog talks about Fundfina, a startup that is part of the Financial Inclusion Lab. The Lab is an accelerator program supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

“I will never come out of this vicious cycle”, says Rajan Lal, 36, who runs a small kirana shop in Bihar’s Mithapur area. On average, Rajan sees 20-30 customers visit his shop and buy goods worth around INR 3,000 (USD 41) each day. While setting up his business, Rajan did not even consider seeking credit from a formal financial institution because he had always heard that formal institutions only finance bigger businesses. Moreover, since Rajan’s business was new, he lacked sufficient documentation for proving the business’s eligibility for a bank loan. Thus, approaching a bank was out of the question.

Rajan used up all his savings and liquidated the land he inherited to meet the initial cost of setting up his business. During festive seasons, he makes brisk sales and rotates the inventory well. Faster rotation of money and a decent profit help Rajan repay supplier credit in time. However, sales and profit drop during the lean season. This forces Rajan to borrow money to replenish the working capital to keep his business afloat.

To borrow for working capital, Rajan reaches out to friends and informal moneylenders during the lean season. The money lenders charge usurious rates of interest and often demand untimely repayments. Many a time, he is forced to clear off the debt and harassment from one moneylender by taking on a fresh informal loan from another lender. Thus, the cycle of borrowing continues.

The burning question is: Can Rajan come out of this vicious cycle of borrowing?

Dismal access to credit

Rajan’s credit problem is, unfortunately, a norm rather than an exception. India is home to 64 million micro and small enterprises (MSEs) run by people like him. Although MSEs contribute significantly to the economy and employment, several factors obstruct their access to formal financial services. Most MSEs lack any formal or documented financial history. This affects their ability to borrow from formal lending sources or institutions. Moreover, such institutions hesitate to serve this segment due to the high cost of acquisition (CAC) and high operational costs.

Despite the government’s concentrated efforts to increase the number of financing options for MSEs in recent years, the addressable credit gap in the MSE sector is estimated to be INR 30 trillion (USD 401 billion).

Fundfina’s eureka moment

Before founding Fundfina, the five co-founders had known each other for more than a decade—either since their kindergarten days or as a result of working together. But what triggered them to join forces and found Fundfina?

Rahul, one of the co-founders, started a small business and like most of India’s MSE owners, faced an issue with availing formal credit. Intensive documentation, long turnaround time (TAT) in processing and decision making, and the hassle of in-person visits made his entrepreneurial journey tedious and his dreams frustratingly distant. Rahul wanted to overcome such barriers not only for his enterprise but for other MSEs as well and got into discussions with the other co-founders. They saw this as an opportunity to have a positive impact on the lives of millions of such entrepreneurs. And thus, Fundfina was born.

Bringing in the change

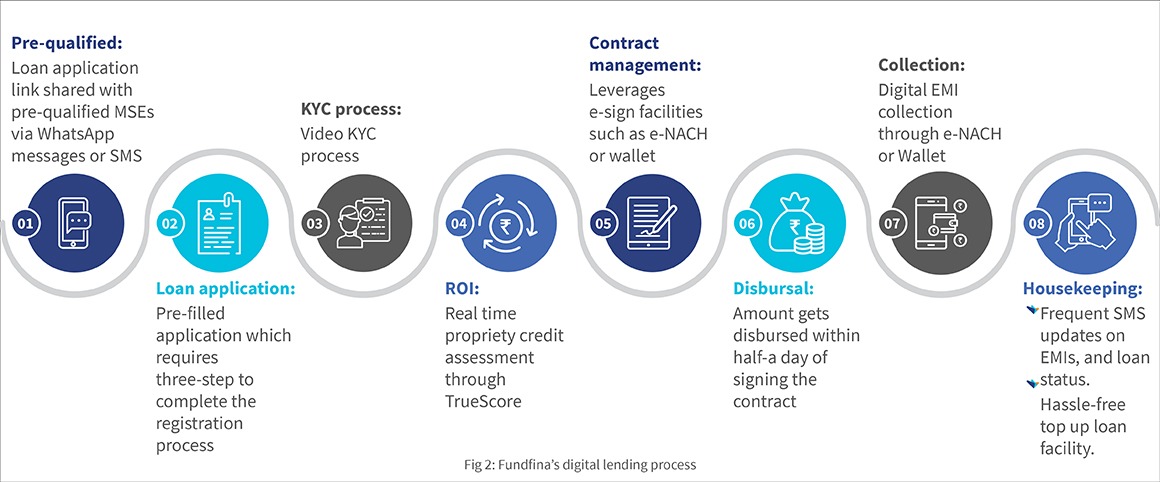

Founded in 2017, Fundfina is a digital lending platform focused on economical MSE financing that rides on alternate data and deep technology employing artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML). The entire process is digital, starting from loan origination to disbursal. It addresses the unmet credit needs of the MSE segment by providing easy, cost-efficient, and technology-driven financing solutions.

Fundfina’s lending model is built on the pillars of accessibility, affordability, and appropriateness.

Accessibility

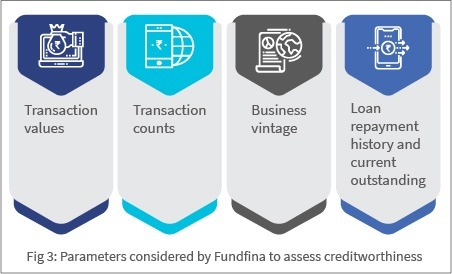

Formal institutions demand several documents, such as income tax returns, GST registration of the business, and previous transaction history, to assess the creditworthiness of MSEs. In contrast, Fundfina uses alternate data through its proprietary tool, TrueScore, to assess MSEs using an additional set of parameters (shown in the figure below).

Affordability

The loan amount and interest rate for each borrower are decided based on their TrueScore assessment score which takes into account the MSE’s repayment capacity. Partner microfinance institutions disburse the loan into the borrower’s mobile wallet or bank account within 12 hours of approval.

Appropriateness

Fundfina understands that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for different MSEs. Hence, it offers a range of customized unsecured financing products, including short-term working capital and long-term financing with a flexible repayment schedule, for each MSE segment. Fundfina understands the volatility involved in running small businesses and, therefore, offers cash-flow-based lending.

TrueScore assesses the amount of credit for which an MSE is eligible based on the business’s repayment capacity. This mitigates delinquency and default rates and enables the borrower to build a strong credit history. The startup also supports MSEs during financial adversities by offering payment holidays and offline agent support through its partner microfinance institutions.

The impact made on the LMI segment

Ninety percent of Fundfina’s customers are small enterprises. The borrowers are from suburban towns and villages, and 80% are sole proprietors typically running unregistered businesses.

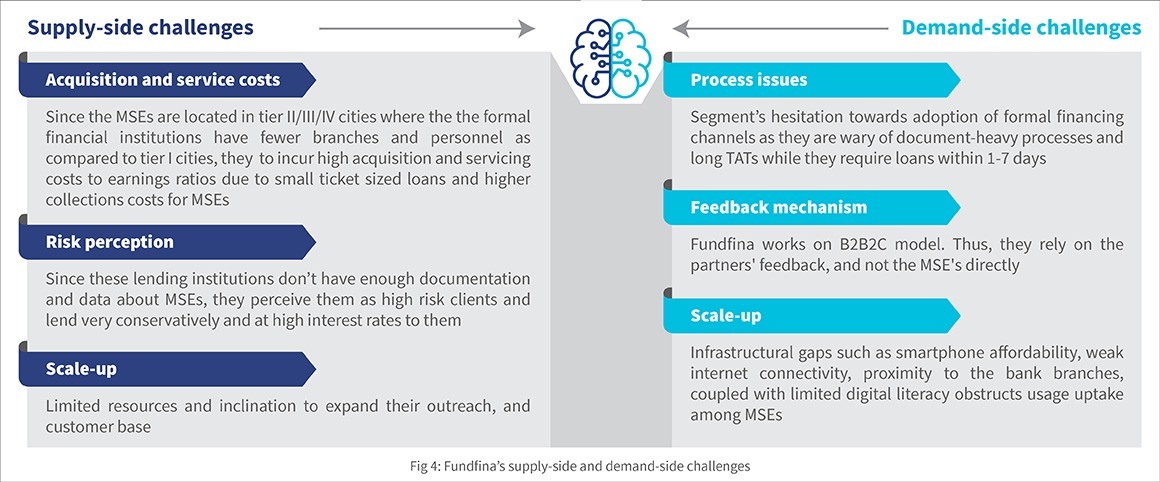

The roadblocks: Fundfina’s path to success has not been easy

Fundfina addresses these challenges as described below:

Addressing supply-side challenges:

- Reduced CAC through partnerships with hyperlocal players: Fundfina has been partnering with several MFIs and on-ground institutions. Under this B2B2C model, the onus to collect repayment is on the partner MFI, which reduces the overall cost of acquisition and serving the customers.

- Risk Mitigation: Fundfina does not lend on their loan books. The partnership-based model helps to mitigate the delinquency risk from the borrowers, and thus reduce operational costs.

- Revenue stream: Besides their supplier lending partners, the startup also commercializes its proprietary tool “TrueScore” by sharing application programming interfaces (APIs) that can be used by other FinTechs. Their “Lending-as-a-service” APIs help FinTechs and other lending enterprises to offer quick and flexible credit to MSEs. The stack automates the entire lending process from application submission to credit disbursement. This provides a convenient yet robust lending tool for their partner institutions and generates additional revenue for the Fundfina team.

Addressing demand-side challenges:

- Handholding support: Fundfina leverages the knowledge and market intelligence of its partners’ field staff to add new-to-credit customers to its list and to get feedback from the end-client MSEs on the current offerings. The phygital approach ensures adequate handholding support is extended to

- Curated lending products: Fundfina offers need-based customized financial products. This helps MSEs understand and appreciate the convenience that formal financing offers, and simultaneously spreads positive word of mouth for the startup. With this, the startup continues to actively explore new avenues to boost its business, even as it keeps existing customer segments engaged.

Support from the FI Lab

Fundfina’s passion to serve the MSE segment inspired them to seek a nuanced understanding of the MSEs’ pain points and expectations, and to continue building customized and impactful solutions for them.

To fulfill this objective, the FI Lab through CIIE.CO and MSC provided mentoring support, and boot camp sessions on relevant business topics. MSC, leveraging its Market Insights for Innovations and Design (MI4ID) approach, gathered insights around the perspective of MSEs on Fundfina’s current financial product offerings and also identified tweaks to make the offerings relevant. The support also helped Fundfina to understand the segment-specific behavior, biases towards digital financial products, and their readiness to adopt them.

The road ahead: Scaling responsibly

Over the next five years, Fundfina plans to reach 10 million micro-merchants and a portfolio of USD 1 billion. Fundfina aspires to become a one-stop-shop for micro-merchants that goes beyond credit and offers a suite of financial and tech-based products in insurance, current and savings accounts, expense management, and inventory tracking, among others. The road ahead for the Fundfina team may be long, winding, and occasionally treacherous but the team is ready for the ride! This will surely help millions of Rajans and their MSEs to continue to plug the gaps in India’s growth story.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that make a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat

Reimagining the way we examine women-run businesses

In collaboration with L-IFT, MSC has been running the Corner Shop Diaries Project, which involves research using the Financial Diaries methodology. Based on an analysis of six months of global diaries data through a gender lens, this slide deck explains significant differences between men-run and women-run enterprises. It further discusses the role of social norms and what is needed to reimagine how we examine women-run businesses.

Why should salaries be monthly when expenses are daily? Welcome, FlexiSalary!

This blog is about a startup under the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world – Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

Startups are rarely known to follow conventional wisdom. They believe in turning any traditional business model on its head. Shantanu Singh and Eral Ravi also did something similar when they decided to transform their childhood friendship into an entrepreneurial partnership. Both come with 18+ years of consulting and practice experience human resources and have a strong understanding of the market forces in this domain. The third co-founder, Aashutosh Chaudhary joined them as a developer when they were building their first startup, Unnati Online—a recruitment technology company—and ultimately rose to become a co-founder and CTO at Flexi Salary.

When it all began

The genesis of Flexi Salary is rooted in Unnati Online. Shantanu and Ravi launched 30 “Rozgar Kendras” during their stint at Unnati – a tech-enabled employment exchange for hiring informal sector and entry-level workers – in Gurgaon. Nearly 20,000 blue-collar workers registered at these Rozgar Kendras within two to three months. This stint gave the founders a chance to observe a large number of workers closely and interact with them. They noticed that nearly all workers were visibly strapped for cash and relied extensively on social borrowing, especially after the 15th of the month.

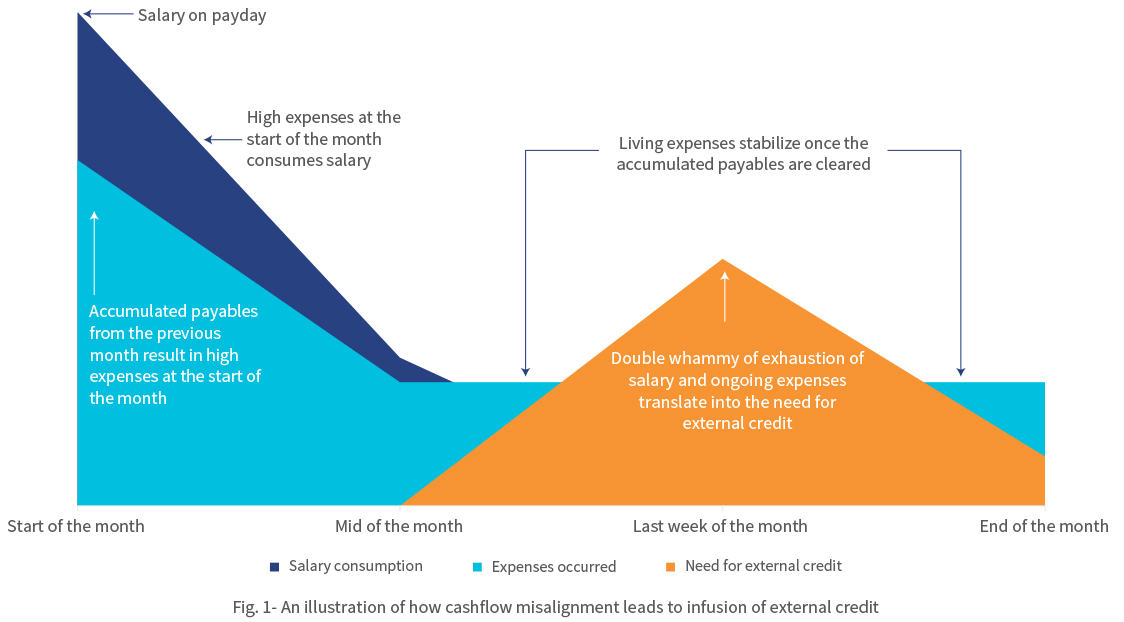

Although “living paycheck-to-paycheck” and “waiting for salary day” have become an accepted way of life for millions of Indians, the founders recognized that these are symptoms of a deep-routed misalignment in cash flow. They believed that FinTechs that provide credit access acted as temporary pain-relievers, as they merely addressed a symptom (an immediate cash crunch) rather than solving the underlying problem (cashflow misalignment). The following graphic illustrates how cash misalignment comes into being.

The figure above represents the cash-flow pattern of a salaried employee from the low- and middle-income (LMI) segment across a month. Expenses peak at the beginning of the month due to recurrent liabilities, such as outstanding bills, rent charges, and so on. Often these overdue bills are pushed to the next payday, which can be any of the first seven days of the next month. Once the employee clears the post-dated bills at the beginning of the month, the expenses decrease but not significantly since the living expenses remain consistent. The steady decline in funds as the month progresses creates a need for external credit. The cycle repeats when the next payday arrives and the bills for the previous month are overdue. This leads to a dreadful phenomenon of living paycheck to paycheck.

Flexi Salary understood that the “monthly salary” system, that is, the mindset of “wait till month end to get paid” generates a cash flow mismatch that causes financial distress for LMI households in India every month. The disruptive question was in front of them—“When expenses are daily, why not income?”

The founders envisioned a new salary system to solve this problem, which would give workers instant access to the money as and when they earned it. The founders understood that this mismatch was an overwhelming problem faced by millions of Indians and therefore was an opportunity to build a company to cater to this large market demand. And so, Flexi Salary was born.

No more monthly salaries

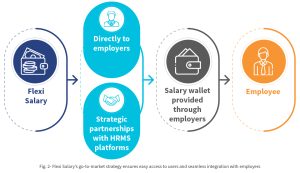

Flexi Salary is a new “instant salary” system in which employees are paid immediately for every workday. Every workday, the day’s salary is loaded into each employee’s salary wallet. As employees work through the month, their earned salary accumulates in their salary wallet. Instead of waiting until the month’s end, employees can withdraw their earnings from their wallets any time they need money. This is done by real-time on-tap liquidity provided by Flexi Salary and their partner NBFCs, which offers timely access to salary for employees. The employees can thereafter repay the withdrawn amount when they get paid the full salary by their employers at the end of the month.

Unlike other FinTechs in this space, Flexi Salary not a loan app. It is not an app that users can use to take credit in a piecemeal manner to meet their liquidity needs. Instead, it provides the customers with continuous access to funds that they have already earned. Flexi Salary stays true to its mission by offering its product to employees through their employers alone. The startup partners with companies that enable the Flexi Salary system for their employees. Once an employer introduces the wallet in the workplace and the employees choose this option, they do not have to wait for the payday or seek additional approval from their employer to withdraw their daily salaries—Flexi Salary’s app handles these aspects.

Flexi Salary has partnered with lenders that provide liquidity flexibly to the users at any time of the month. When the user receives their wages at the end of the month, they can repay the availed amount to Flexi Salary. Neither the employer nor the payroll teams need to get involved. The payroll team and their usual operations can continue as per the established monthly cycle, while Flexi Salary’s wallet powers each employee with the convenience of flexible salary.

Besides being a workplace perk, the facility to avail salary flexibly ensures that the employees are well-funded, which minimizes the chances of having to look elsewhere to make ends meet, thereby falling into a potential debt trap. Flexi Salary has also partnered with leading human resource management system (HRMS) players in the industry, including Quess Corp, Adetto HR, and Hono HR. Powered by such partnerships, a company that uses any of these HRMS solutions can implement Flexi Salary easily within their workplace in a plug-and-play mode.

Battles to win:

The founders believe in validating the product—and what better way to do this than by engaging HR leaders and other decision-makers in trials before rolling it out to the employees. While Flexi Salary has had significant early traction in its journey, generating trials for such leaders has been an uphill task. Moreover, the uncertainty in the business environment posed by COVID-19 has prolonged some of the business discussions indefinitely.

Adhering to the same spirit with which they set out to solve the problem of cash flow misalignment, Flexi Salary took these roadblocks head-on with grit and commitment. The team has used the personal networks of founders and connections from investors. One of the advantages of Flexi Salary has been Shantanu’s alumni network at Xavier Labor Relations Institute- XLRI, which has one of the best human resources MBA programs in the country. The team has accessed the alumni network to tap into HR leadership in various firms in India. Not letting the crisis go to waste, Flexi Salary has been focusing on improving its product through continuous product development and pilots. These refinements will ensure that the product is scalable. As soon as the second wave recedes, the team can hit the ground running to realize their dream of enabling flexible salaries for everyone in India.

Support from the FI Lab

Through CIIE.CO and MSC, the Lab has been helping their business in two phases, besides making the right connections.

In the first phase, the Lab helped Flexi Salary to identify the appropriate product positioning of its app, based on ground-level research with white-collar as well as blue and grey collar employees to identify their problems and needs. Using a human-centered design framework on the salary wallet model and expense allowance model, MSC helped Flexi Salary to strike a balance with blue-collar as well as entry-level white-collar workers.

In the ongoing second phase of the TA, the Lab has been helping Flexi Salary in its scale-up by identifying companies that can act as aggregation points through strategic partnerships. Identification of such strategic partnerships can unlock access to many employers and thus, employees. We have also supported Flexi Salary in developing its business development strategy and implementation of the same to ensure that the team can scale up faster.

Collectively, the advisory support of the Lab will ensure that Flexi Salary finds the right product-market fit at an early stage in its journey. Once this is achieved, Flexi Salary would scale up efficiently through bootstrapping and minimal external funding.

Way forward:

The founders want to establish the concept of flexible salaries across industries. In the short term, the founders hope to popularize Flexi Salary as the “employee-friendly” way of paying salaries to employees. They hope to partner with companies in a diverse range of industries to enable Flexi Salary for their employees making the product industry-agnostic. Over the next five years, they hope to replace the concept of “monthly salary” with flexible salary and establish it as the preferred salary payment system across India Inc.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that are making a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat