COVID-19 has affected millions of lives and livelihoods across the globe. India’s experience with the pandemic has been particularly painful. MSC conducted a three-phase study to understand and assess the impact of the pandemic on the FinTech ecosystem. Our initial report presented the impact of COVID-19 on Indian FinTechs and various strategies that helped them survive and recover. This report shines a light on how the FinTech ecosystem has progressed and adapted to the new normal.

Impact of COVID-19 on Fintech: Bangladesh

Bangladesh managed to contain COVID-19 swiftly. Consequently, the pandemic barely affected some FinTechs while others, such as e-commerce, online essential item delivery firms, and payment wallets, even thrived because of it. However, early-stage start-ups struggled as they depend heavily on access to banks and investors for funding, which has been scarce during these times.

This report presents the impact of the pandemic on the operations, revenue, and coping strategies of FinTechs in Bangladesh. It also explores the investor sentiment and impact of government policies on the development of FinTechs. The report further provides recommendations for relevant stakeholders to help affected FinTechs recover.

The Helix Institute at MSC Masterclass with Esselina Macome, CEO, FSD Mozambique.

Esselina Macome, CEO of FSD Mozambique addresses our Master Class today. She speaks at length about her professional journey, key achievements, challenges, and lessons learnt. In this conversation, she delves deeper on:

The medium- to long-term impact of COVID-19 on the inclusive finance sector;

How financial markets can address the financial constraints of low- and moderate-income populations effectively;

The need for a renewed focus on financial inclusion, considering COVID-19 has undone years of progress in inclusive finance initiatives; and

Recommendations for the financial sector, development community, and multilateral organizations to future-proof against such crises.

Click here to watch more of our master classes.

Vietnam’s changing digital landscape: The transformation of FinTechs to super apps in the time of COVID-19

Twenty-eight-year-old Van from Ho Chi Minh city was used to handpicking fish, meat, green vegetables, and other food items at local markets and supermarkets. However, when the government announced a social distancing policy in March 2020 due to COVID-19, she had to gradually limit her purchases to essential food items on the mobile app of a food-delivery FinTech.

Van is a typical Vietnamese millennial who has almost stopped visiting shops since the social distancing measures were introduced in Vietnam. This behavioral change by customers like her resulted in a rapid increase in traffic in online shopping and digital payment platforms. The total number of transactions of the first quarter of 2021 through the electronic clearing and financial switching system of the Vietnam National Settlement Joint Stock Company (Napas) increased by 103% compared to the same period last year.

Meanwhile, the adoption of e-wallets increased in the country, driven by several factors. These include: 1. an increase in peer-to-peer (P2P) money transfers, bill payments and payment-to-merchant (P2M payments) services for essential items owing to the lockdown; 2. social distancing measures; and 3. an aversion to exchanging physical cash for fear of infection. MoMo, for instance, reached 20 million users as of September, 2020, which represents nearly 100% growth in a year. ZaloPay also recorded a strong growth of 300% from January to August, 2020 through digital money transfers and payments.

While Vietnam managed to contain the COVID-19 pandemic early on, several sectors were hit hard—particularly airlines, tourism, hospitality, and transportation. In addition, early-stage startups have struggled as they depend heavily on access to banks and investors for funding, which has been scarce during these times.

Curiously, some sectors saw minimal impact from the pandemic or even thrived because of it. These included e-commerce, online food delivery firms, payments wallets, and payments applications. Digital payments and online shopping are expected to shape the “new normal” in the post-COVID era due to restricted mobility and aversion to cash transactions, as mentioned above.

The impact of COVID-19 on products and business strategies

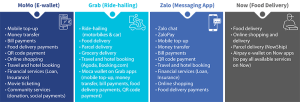

- The demand for digital payment solutions, such as mobile payment, QR code payment, and card payment has increased. It has pushed e-wallet players, such as MoMo, VNPay, Moca (on Grab), ViettelPay, and ZaloPay to widen their QR code presence at merchants, both online and offline, to increase user convenience. For example, in the first quarter of 2021, there were 395 million transactions carried out via mobile phones—an increase of 78% compared to the same period in the previous year.

- Online shopping services are now offered not only by supermarkets or e-commerce sites but also by mobile apps, such as MoMo, Grab, Now, and ZaloPay as people isolate themselves at home.

- Mobile wallet apps, such as ViettelPay, ZaloPay, and MoMo have started pivoting or extending their offerings beyond payment facilities by adding more financial services, such as loan applications and non-life insurance products on their platform. They now also offer many appealing promotions to new users, such as discount vouchers and cash-back offers when they make bill payments including utility, internet, and television services.

- Many FinTech players said that COVID-19 has galvanized the speed of collaboration among them and traditional insurance companies to launch microinsurance products to the market. PVI and MoMo, for instance, launched the Corona++ nano insurance product to serve vulnerable LMI clients.

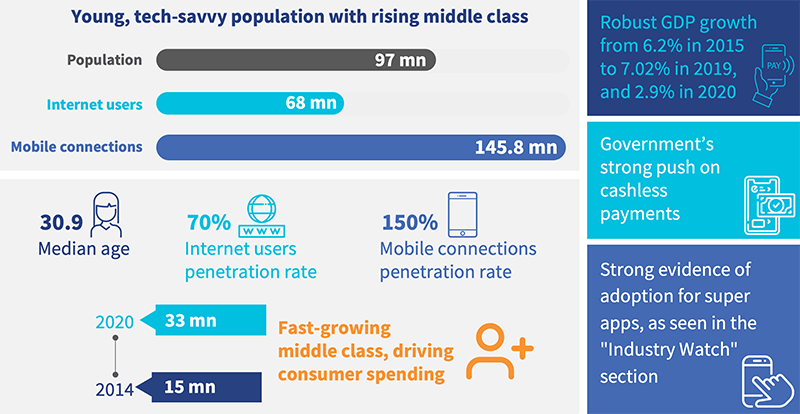

Why is Vietnam an ideal nurturing ground for the development of super apps?

How have the big guys fared? (Industry watch section)

MoMo was officially licensed in 2015 and raised USD 100 million in its Series C funding round from Warburg Pincus in January, 2019. MoMo is the most popular mobile wallet in Vietnam with a fast-growing number of users: from 10 million in 2019 to 20 million in the third quarter of 2020. Recently, MoMo was awarded the “Most-used financial application of 2020” (2020 Vietnam Top 10 Finance Applications by MAU). MoMo’s wide network of 100,000 payment acceptance points and 20,000 partners continues to be a solid foundation for its path to becoming the top super app in Vietnam.

Grab, at a valuation of USD 14 billion, has plans to focus on the Vietnamese and Malaysian markets to grow as a super app. This will be one of Grab’s initial steps to dominate the Asian market. Grab accounted for 73% of the market share for ride-share trips completed in the first half of 2019 and has maintained its dominance in Vietnam since then. It expects that 50% of Vietnamese will use Grab by the end of 2020, compared to 25% in 2019. During the ongoing pandemic, Grab has introduced the GrabMart service on its app to enable people to shop essential goods and groceries online. By committing to invest up to USD 500 million in the Vietnam market over the next five years, Grab is definitely the strongest player in the competition.

Zalo, the most popular messaging app in Vietnam with 100 million users, has built an e-wallet ZaloPay. For the past three years, with capital support from the only unicorn of Vietnam, VNG Corporation, Zalo plans to follow in the footsteps of its Chinese counterpart, WeChat, and build a super app by riding on the huge user base of its messaging app. The number of transactions on ZaloPay recorded an increase of 300 percent in the first eight months of 2020 after they launched a new feature called “Chatting is Transferring.” This feature allows Zalo users to transfer money via ZaloPay when they are chatting with just a few taps on their mobile phone.

Zalo, the most popular messaging app in Vietnam with 100 million users, has built an e-wallet ZaloPay. For the past three years, with capital support from the only unicorn of Vietnam, VNG Corporation, Zalo plans to follow in the footsteps of its Chinese counterpart, WeChat, and build a super app by riding on the huge user base of its messaging app. The number of transactions on ZaloPay recorded an increase of 300 percent in the first eight months of 2020 after they launched a new feature called “Chatting is Transferring.” This feature allows Zalo users to transfer money via ZaloPay when they are chatting with just a few taps on their mobile phone.

Now is the most popular food delivery service in Vietnam. With approximately 200,000 merchants and partners on their platform Now is one of the most popular delivery applications in Vietnam. The brand is owned by the leading culinary media and restaurant platform in Vietnam, Foody. It received an investment worth USD 64 million from the Singapore-based consumer Internet group Sea, formerly known as Garena, in 2017. The investment intended to help Sea expand its payment platform AirPay (ShopeePay) which launched in Vietnam in 2014.

Now is the most popular food delivery service in Vietnam. With approximately 200,000 merchants and partners on their platform Now is one of the most popular delivery applications in Vietnam. The brand is owned by the leading culinary media and restaurant platform in Vietnam, Foody. It received an investment worth USD 64 million from the Singapore-based consumer Internet group Sea, formerly known as Garena, in 2017. The investment intended to help Sea expand its payment platform AirPay (ShopeePay) which launched in Vietnam in 2014.

Now will benefit greatly from the development of the digital ecosystem under the Sea group across other consumer touchpoints, including gaming (Garena), and Shopee—Vietnam’s most popular e-commerce platform. For instance in 2020 Now was integrated to Shopee application to take advantage of 38 million visits per month from Shopee.

The top-four super apps in Vietnam with their most popular services

Vietnam is an attractive market for development of super apps due to high internet penetration and high smartphone ownership. Digital payments and online shopping services provided by the super apps are shaping the new normal in the post-COVID era due to restricted mobility and concerns over the exchange of physical currency. The regulatory sandbox for FinTechs which will be released by the end of this year will foster the development and launching of new services such as digital credit, digital savings, InsurTechs and WealthTechs by super apps.

Impact of COVID-19 on FinTechs: Vietnam

While the pandemic barely affected some FinTechs in Vietnam, such as e-commerce and online food delivery firms, others were hit hard. Early-stage start-ups struggled as funding from banks and investors dried up.

This report highlights the impact of COVID-19 on the operations, revenue, and coping strategies of FinTechs in Vietnam. It explores investor sentiments and the impact of government policies on the development of FinTechs in the country. The report further provides recommendations for relevant stakeholders to help affected FinTechs recover.

Vaccine hesitancy—an impending barrier to India’s COVID-19 vaccination program

Background

Vaccine hesitancy can jeopardize India’s plan to defeat COVID-19 as it scrambles to vaccinate its population in the wake of the second wave of the disease. While the second wave seems to be receding, the possibility of an intense third wave looms large. The fear of a third wave is real because the rate of vaccination has been slow, the possibility of more virulent strains of the virus emerging is high, and the need to reopen economic activity is critical—though it may lead to people adopting COVID-inappropriate behavior, as seen from our studies in the past.

In this situation, the best possible solution to mitigate the risk of a third wave is to quickly vaccinate as many people as possible to break the chain of transmission and reduce fatalities. Enforcing COVID-appropriate behavior and building the capacity of the health system has to continue in parallel.

Currently, progress in vaccination has been slow because of an imbalance in supply and demand. However, as per the plans released by the Government of India, vaccine supply should normalize by July-Aug 2021. The plan is to have more than 2 billion vaccine doses by Dec, 2021, which is enough to vaccinate the eligible population. The availability of vaccines has to be complemented with a massive ramping up of the supply chain, vaccination centers, and healthcare staff to distribute and administer the vaccine. Even if availability, distribution, and administration of the vaccines are sorted, achieving complete vaccination of the eligible population by Dec, 2021 is a daunting task. And the reluctance of people to get a shot in their arms, or vaccine hesitancy, remains a key factor that can jeopardize the plan.

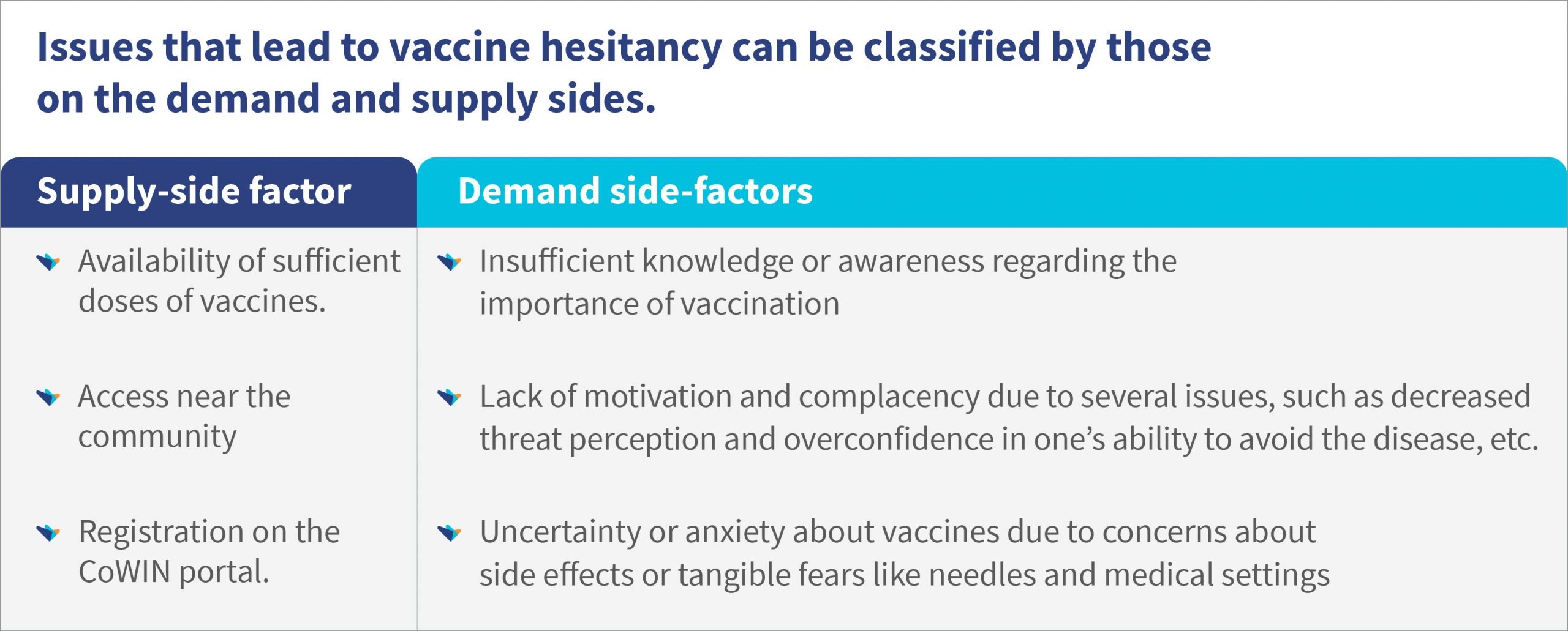

According to the World Health Organisation, vaccination hesitancy refers to the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccine services. It is influenced by factors, such as complacency, convenience, and confidence. Issues of vaccine hesitancy have already started cropping up in different parts of the country and across the world. These need to be tackled on a priority basis as misinformation and complacency can spread quickly.

For example, in the USA, the seven-day trailing average of vaccination has dropped from the peak of 3.7 million a day in mid-April to less than a million per day toward the beginning of June, 2021. About 41% of the population is fully vaccinated and 51% have received at least one dose—a large part of the population remains unvaccinated. This is primarily due to vaccine hesitancy and it is almost certain that India will face this issue as the availability increases.

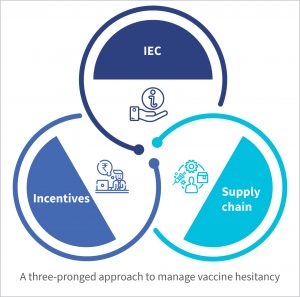

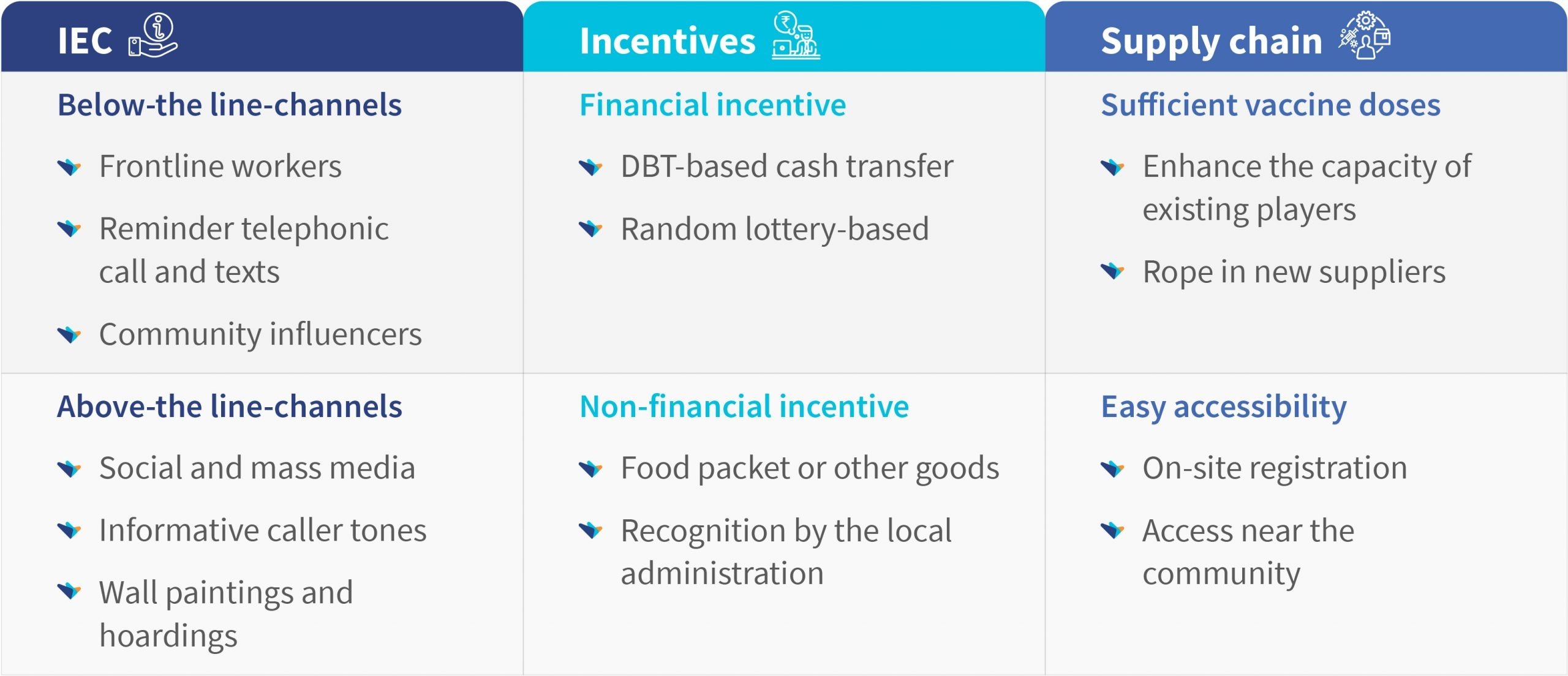

A three-pronged approach that combines interventions from both demand and supply sides is needed to manage vaccine hesitancy. Information, Education and Communication (IEC) is the most important “prong” in the approach to reduce vaccine hesitancy. It can be even more effective if coupled with the other prongs of incentives and an efficient supply chain. The following table provides a list of ideas across these three elements to manage vaccine hesitancy.

The following table provides a list of ideas across these three elements to manage vaccine hesitancy.

Information, Education and Communication (IEC)

IEC can be through below-the-line (BTL) or above-the-line (ATL) channels. The key is to ensure that all IEC campaigns are carefully planned, executed and monitored with active feedback loops to ensure that messages are adjusted and misinformation is addressed rapidly. MSC’s work on the effective communication of government to people (G2P) benefit payments provides important insights for this.

Below-the-line IEC channels

- Frontline workers: People-to-people awareness campaigns can be launched that utilize frontline workers like ASHAs, Anganwadi workers (AWWs), and auxiliary nursing midwives (ANMs). The frontline workers can either reach the eligible candidates or specific target groups directly to motivate and track them. Mechanisms for supportive supervision and monitoring may be set up.

- Last-mile service delivery points: Campaigns can also be launched through the vast networks of citizen-facing outlets developed to deliver products and services to the rural population, such as Citizen Services Centres (CSCs), Public Distribution System (PDS) dealers, fertilizer dealers, and self-help groups, among others. MGNREGA work sites can also be used for this purpose.

- Through reminders and telephone calls: Health personnel like Community Health Officers (CHOs), Block Community Process Managers (BCPMs), and ANMs may be deployed to speak to hesitant clients through phone calls to motivate and convince them to get vaccinated.

- Through community influencers: Community influences like religious and community leaders, gram pradhans, panch, and ward members, among others, may be identified and engaged with. They can play a critical role in influencing the vaccine-hesitant group.

Above-the-line IEC channels

- Regular activities that explain the importance of vaccination, its safety, efficacy, and possible side effects need to be initiated and increased. Such activities, including social media campaigns, mass media campaigns, informative caller tones particularly voiced or fronted by a famous non-controversial celebrity like sports personality or film stars, wall paintings, and hoardings could prove vital in dealing with misinformation and influencing the decisions of people to get vaccinated. A lot of action is already happening through ATL channels but it needs to increase as we vaccinate early adopters and start to target hesitant population.

Incentives

Incentives can play a key role in motivating people to take vaccines. These may be in the form of financial incentives or non-financial incentives.

- Financial incentives: One form of financial incentive can be DBT cash transfers to the households if all the eligible members get vaccinated. It can generate healthy competition among the residents of an area or community to take up vaccination.

A lottery system could also be tried where every vaccinated person is eligible for a lucky draw once that area, block, or district reaches a certain threshold of vaccination. A few big prizes can be announced to motivate people to participate in it. FLWs could also be incentivized to get their eligible catchment population vaccinated. Gram panchayats could also be incentivized to motivate people in their jurisdiction to get vaccinated.

- Non-financial incentives- Food packets or other goods can be provided if all members of a house are vaccinated. This may be a top-up to the already sanctioned quantity of ration through PDS. Another way could be by recognizing those households as “Adarsh” (ideal) houses, where all the eligible members are vaccinated. These households can be felicitated by the local administration with a certificate, sticker, badge, or similar token.

Mandatory vaccination status for non-essential events that attract attention can also be tried as positive reinforcement for vaccination. Such events include entering famous places of worship, unrestricted air/train/road travel, entry in sport stadiums, gyms, swimming pools, conducting functions like weddings, and holding political gatherings only when organizers are vaccinated, among others.

Supply chain

The availability of vaccine doses and its easy accessibility play a critical role in influencing the issues related to complacency and convenience, and in turn affect vaccine hesitancy.

Ensure sufficient doses of vaccines

As per the National Health Authority, the demand-supply gap in COVID-19 vaccines stood at 6.5:1 at the time of writing, falling from an earlier gap of 11:1. While a lot of work needs to be done to bridge this gap, a strong pipeline of potential vaccine candidates and enhanced vaccine production in the country suggest the gap is set to reduce further.

Access near the community

The government may utilize the existing Universal Immunization Programme (UIP), where ANMs conduct regular vaccination sessions at pre-designated places in the community, such as health sub-centers, Anganwadi centers, and Panchayat Bhawans. In addition, the newly developed health and wellness centers along with their staff could be utilized to augment the vaccination drive. Drive-through vaccination centers may be considered to improve access and visibility.

Registration on the CoWIN portal

People in the age group of 18-45 years have found it difficult to get registered on the CoWIN portal primarily due to two reasons—the limited availability of slots and the limited number of individuals who use phones. As per the TRAI’s press release for May, 2021, the overall teledensity of India was 85.78%, while the rural teledensity was 59.28%. The teledensity numbers for states like Bihar and UP are in stark contrast to more urbanized states like Delhi. Even those who have phones may not necessarily have smartphones and are often unfamiliar with technology. This puts a considerable proportion of the population directly at a disadvantage. Network issues also act as a deterrent. The problem of slots will be resolved once the availability of vaccine doses improves.

To give equal opportunity to all for registration, the government may consider allowing on-site registration for eligible populations. Stakeholders can also utilize alternate channels like self-help groups, PDS shops, fertilizer dealers, and common service centers apart from routine healthcare frontline workers like ASHAs, ANMs, and AWWS, among others.