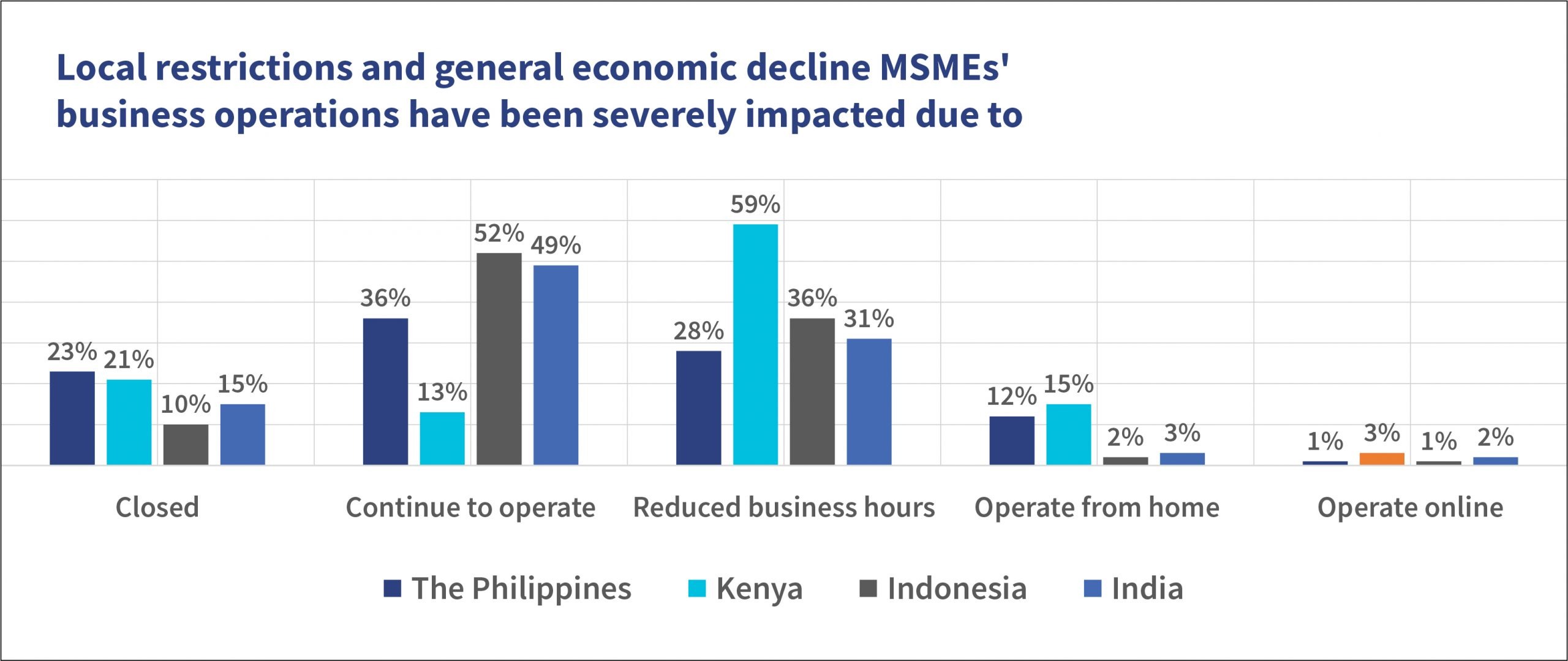

About 17% of businesses surveyed by MSC in India, Indonesia, Kenya, and the Philippines have closed due to local restrictions and low demand for goods and services. Meanwhile, micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in the informal sector fared worse. MSMEs, which have been the pillar for many economies, have been struggling to survive in the post-COVID-19 world.

According to the World Bank, SMEs contribute about 90% of businesses and 50% of employment worldwide. Formal SMEs contribute around 40% to the national GDP in emerging economies. MSMEs have an even higher share in the economy if we include informal enterprises. COVID-19 created a challenging environment for MSMEs and only agile businesses have a better chance to survive the crisis. Yet only a few enterprises have realized that digitization may bring agility and resilience to the operations and expand their reach. In a survey conducted by MSC in India, Indonesia, Kenya, and the Philippines, only 38% of respondents have reported that they either increased the use of digital payments or started using digital modes of payment for transactions.

Digitization brings ample opportunities to MSMEs

Digitization of MSMEs offers them the chance to differentiate themselves from the competition. The 2019 APEC SME Ministerial Statement noted that e-commerce platforms allow SMEs to gain greater access to diverse global markets and can mitigate risk within supply chains. Digitization enables enterprises to implement digital technology to:

- Expand geographical reach and acquire new customers: With the growth of digital platforms, the rising prominence of e-commerce, and the low barriers to entry, MSMEs can expand their market and overcome the limitations of physical location. E-commerce has also paved the way for MSMEs to serve rural and remote customers, ultimately adding to their customer base. In Africa, 82% of the enterprises engaged solely in cross-border e-commerce are micro and small enterprises. E-commerce also offers easy access to the international markets for women-owned enterprises.

- Better customer engagement: MSMEs that operate digitally can manage their customer base effectively by using social media to ensure higher engagement levels. As per a survey of US consumers, in March, 2020, online spending increased by 30%. As customers have radically altered their buying patterns, digitization has become essential to run a business.

- Cost-effective business operations: MSMEs that used the Internet lowered their costs by about 22% to source raw materials, manage inventory, and achieve higher productivity.

- Increased business profitability: MSMEs that spent more than 30% of their budget on Internet technologies raised revenue nine times as fast as MSMEs that spent less than 10%. Digitization can help MSMEs enhance revenue by 26%. In India, MSMEs that adopted e-commerce have reported 27% higher revenue growth than their offline counterparts.

- Higher and better access to finance: As MSMEs increase their digital footprint, they become more visible to banks and lenders. MSMEs can easily access credit as financial institutions can utilize digital data to assess credit risk more accurately.

- Efficient customer credit management: With digitization, MSMEs can track customer credit and also can set a limit of credit for customers. It can act as a risk mitigation measure and keep a check on the credit loss and help maintain an efficient cash flow in the business.

Opportunity comes with challenges

Nonetheless, MSMEs that wish to embrace digitization face various challenges.

- Lack of understanding of how technology helps: MSMEs lack awareness of the benefits of technology. Most MSMEs have doubts about the return on investment from adopting technology. The lack of awareness and skepticism around the benefits lead to low uptake. Furthermore, MSMEs lack the skills to understand and participate in the digital economy, which contributes to the limited adoption.

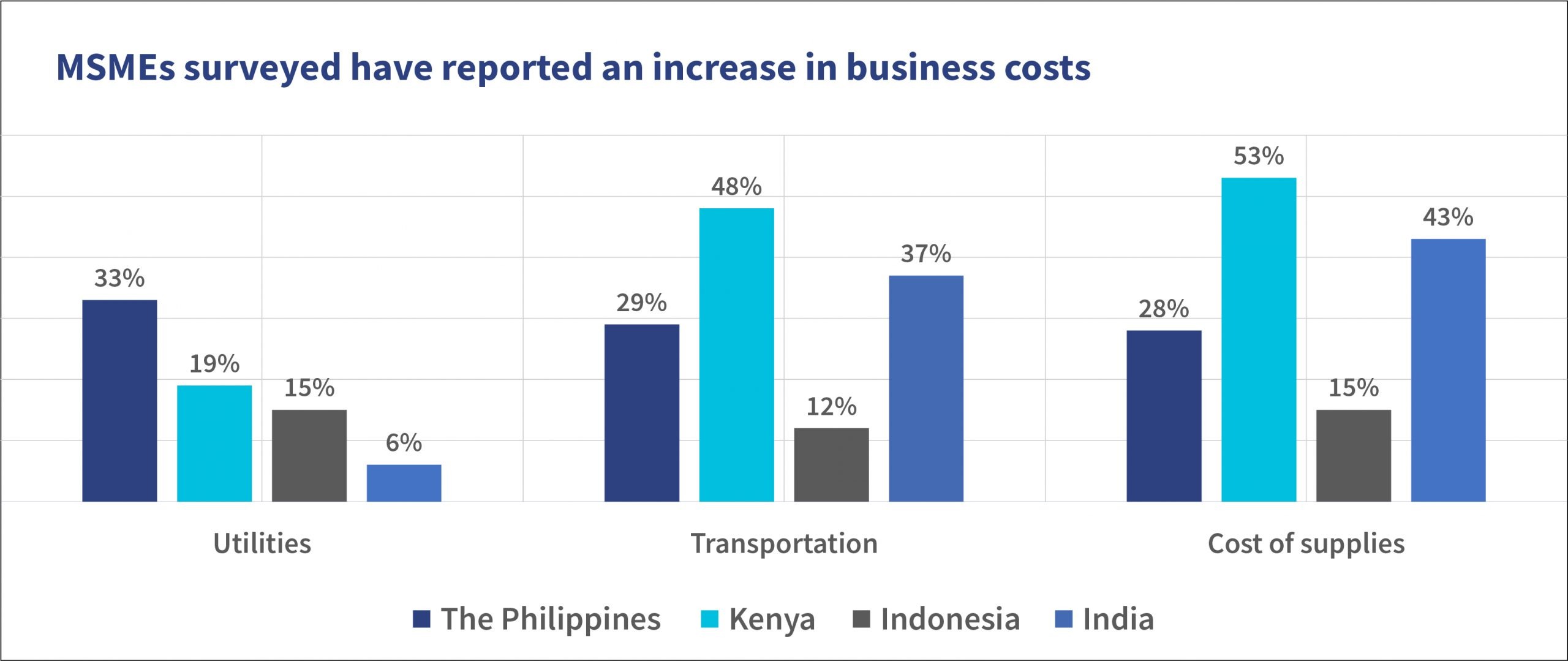

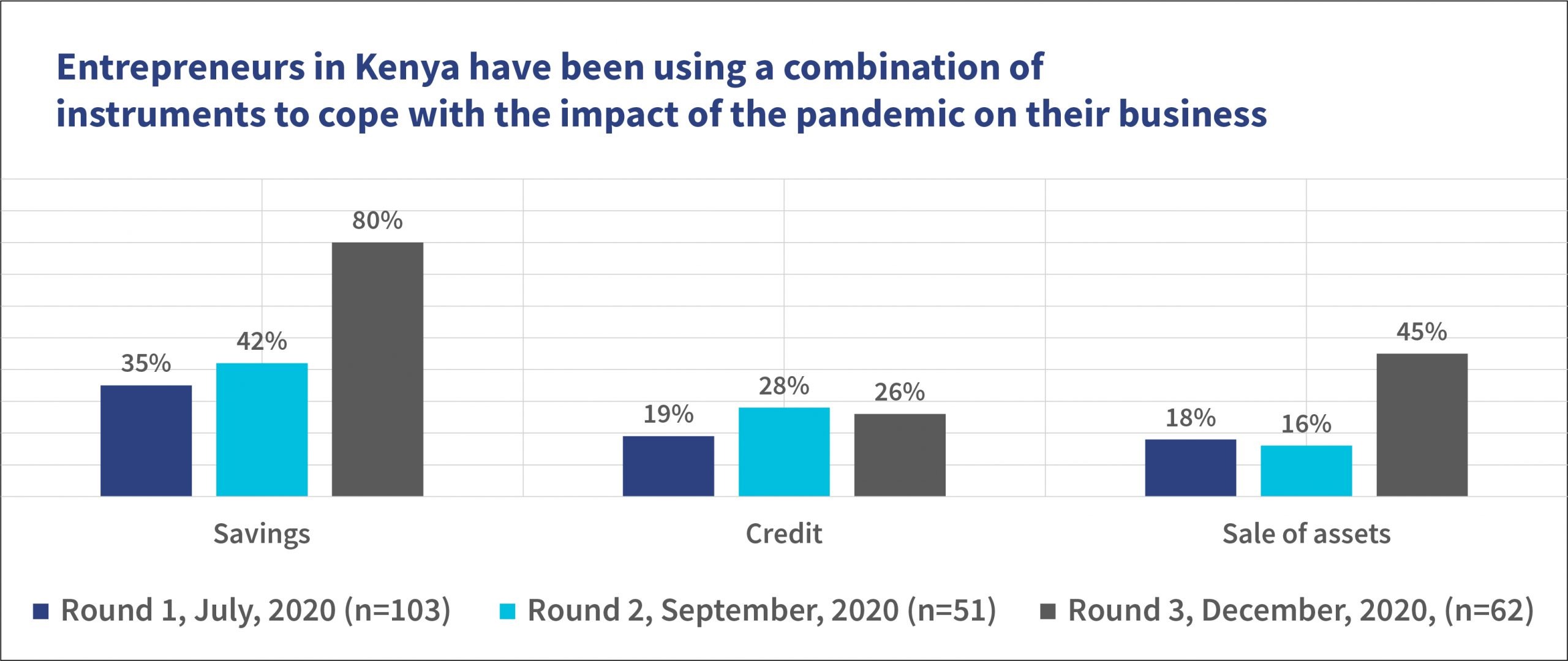

- Cost of technology adoption: A lack of disposable funds to acquire technology for the business limits the ability of MSMEs to benefit from digital technologies. The vast majority of MSMEs have been decapitalized by the pandemic—they have run down stocks, depleted savings, and had to borrow from informal sources just to stay afloat. So, enterprises will need access to credit to resume business and adopt technology and digitize their operations. 19% of enterprises in Africa find the high commissions taken by e-commerce platforms as a major bottleneck. For these businesses, securing loans from traditional banks and financial institutions is a time-taking and tiresome process. The Government of India and the Reserve Bank of India (the central bank in India) have implemented PSB loans in 59 minutes to respond to this challenge. The initiative has digitized the lending process so that a borrower can access a loan within 59 minutes. Such programs that digitize and automate access to finance for MSMEs through a marketplace platform will help entrepreneurs access credit with greater ease.

- Concerns around data privacy and exposure to digital fraud: Cybersecurity firm McAfee estimated the impact of cybercrime on the global economy at nearly USD 600 billion pre-COVID. Post-COVID, the value at risk due to cybercrimes may increase even further as the adoption of digital tools for procurement, payment, inventory management, etc. has risen significantly. While large businesses and government-owned enterprises can track and protect themselves against cyber threats, the associated costs and lack of awareness about these threats make the management of cybercrimes difficult for MSMEs.

What is needed to catalyze the digitization of MSMEs?

MSMEs need better access to e-platforms, better payment and delivery services, streamlined customs procedures, a robust data privacy system, and targeted skill-building to ensure they can benefit from e-commerce.

The first step to digitize MSMEs’ operations is to build the digital capacities of entrepreneurs

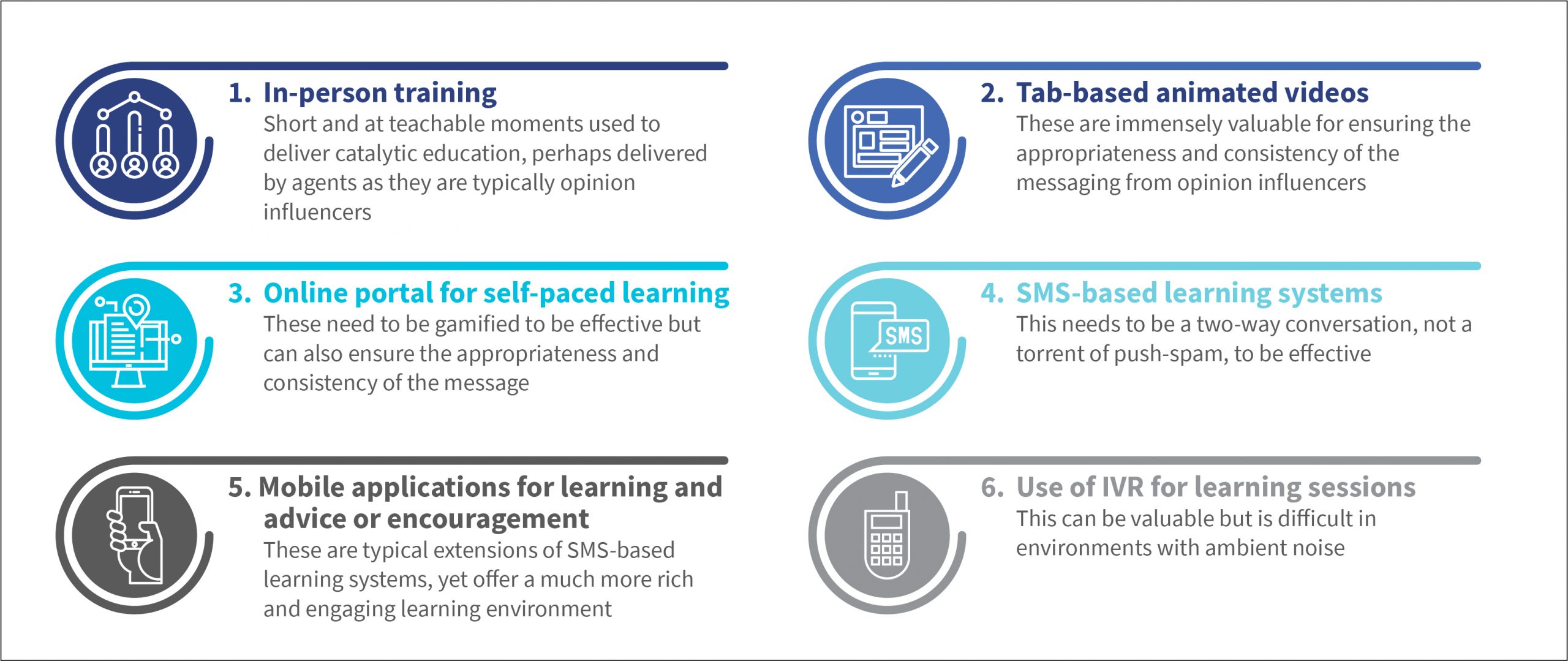

Many MSME entrepreneurs cannot intuitively appreciate the benefits or value proposition of the use of digital technologies. They struggle to trust, navigate, and use technology to market their products and services, receive payments, and access digital financial services. Carefully designed and delivered digital skilling programs based on an understanding of their mental models can enable MSMEs to use digital technology to grow their businesses. While building the digital capability of MSMEs, a mix of the following works best:

Supporting the journey of digitization for MSMEs during the pandemic requires an innovative approach that will allow them to reap its benefits while overcoming challenges. Entrepreneurs need support at all stages of their digital journey, as they start as beginners, move to intermediate level, and acquire experienced status.

- At the beginner level, entrepreneurs are new to the digital world. Influenced by their peer group and family, they start with the use of various social media applications, mostly to communicate and acquire knowledge. At this stage, they need support to enable digital payments for their business, participate in various basic social media and e-commerce platforms, and access credit using digital platforms.

- Once they reach the intermediate level, entrepreneurs become comfortable with using digital tools for functions they have learnt at the beginner level. At this stage, they may need help in using digital tools for intermediate functions, such as customer service and credit management, branding and marketing, participating in value chains and supply chains, and taxation.

- At the experienced level, entrepreneurs are comfortable with digital applications and can navigate applications that support the business. At this stage, they expect assistance on tools on product standardization, copyright, and trademark registration, use of advanced digital marketing including search engine optimizations (SEO), Google Ads, and other marketing tools.

As MSMEs build their skills and embrace technology, policymakers may take steps to support their digital transformation in the following ways:

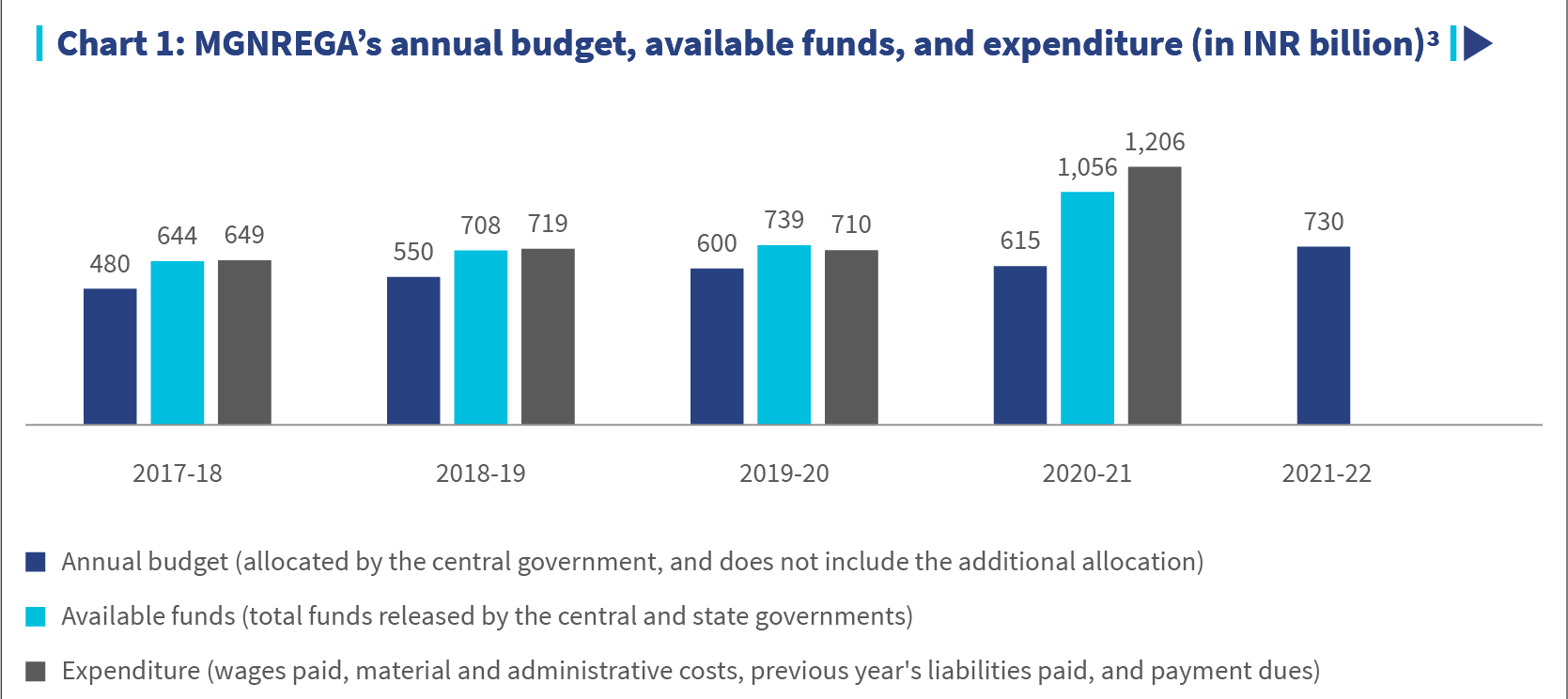

- MSMEs still have significantly low adoption of technology, such as the use of social media and other online channels for business communication. The government may incentivize the use of digital channels by MSMEs and provide access to subsidized credit for MSMEs to digitize. The government may also develop appropriate digital infrastructure to make the digitization of MSMEs possible. For example, the Government of India has recently launched the Digital Saksham Initiative in collaboration with MasterCard to strengthen the ability of MSMEs to market products better through greater know-how and digital payment acceptance.

- Digital literacy will play a role to catalyze the uptake of digital technologies and address skill gaps. Public and private agencies must join hands to promote digital literacy and enhance trust in digital solutions. The government can promote this as a part of the academic and vocational curriculum in colleges and training institutes. In India, the government, EdTech start-ups, and tech businesses have joined hands to help MSMEs to grow their business online.

- Make mobile money and digital credit more accessible and affordable. To promote mobile money in the country, policymakers and think tanks can mandate lower transaction fees. During the pandemic, Kenya and other countries took this step to promote online payment. In Kenya, more than one-fourth of the adult population uses digital credit and most of them use it to meet their needs of working capital. The government may push for the expansion of digital credit beyond consumer finance to cater to the financial needs of MSMEs by nudging or mandating providers to focus on enterprise finance.

- Enable policies to protect users against digital fraud and cybercrime. The government and policymakers can develop suitable policies to ensure that the average user is safeguarded against the risk of digital fraud and cybercrime. The government could also develop and deliver awareness campaigns for users to inform them of key issues and ways to mitigate the risk of fraud.

Although digitization is an ongoing process, the COVID-19 pandemic has compelled MSMEs to transform their businesses through digital means. The digitization of MSMEs will add more revenue to the entire economy. The CISCO 2020 APAC SMB Digital Maturity Study found that a shift of 50% of MSMEs to the digital challenger stage (the enterprises where all core processes are automated and productivity rates are increasing) could add between USD 2.6 and 3.1 trillion to Asia Pacific’s GDP by 2024.

In Africa, MSMEs currently provide more than 50% of GDP. We envisage that as MSMEs digitize, their contribution to the national economies will increase significantly. With the said potential, the time is ripe now to focus on the digitization of MSMEs. Using digital means, the MSMEs can utilize e-commerce, social commerce, and digital payments to support their recovery after their pandemic, while reviving their businesses and building greater resilience to survive similar crises.