The increase in internet accessibility through human-to-human (voice, text chats), human-to-machine (internet searches), and machine-to-machine (Internet of Things or IoT) interactions has led to an explosive proliferation of digital data, with 33 zettabytes of data produced in 2018 alone – a number predicted to increase to 175 zettabytes by 2025 (1 zettabyte is 1 trillion gigabytes). And despite the fact that our digital footprints have increased vigorously, and various data-focused organizations have stepped in to map them, according to this 2016 Mckinsey article only 1% of the enormous amount of data that exists has been analyzed.

Meanwhile, the advent of machine learning and IoT has changed the way we look at this information. Companies are increasingly adopting data analytics to draw insights for their businesses. The analyzed information has helped upend customer expectations, while enabling businesses to optimize operations to unprecedented levels.

This explosion in data and analytics technologies can provide a decisive competitive edge to fintech companies. Below, we’ll explore how they can leverage these tools to their benefit – and the benefit of their customers.

Why should fintechs value data ?

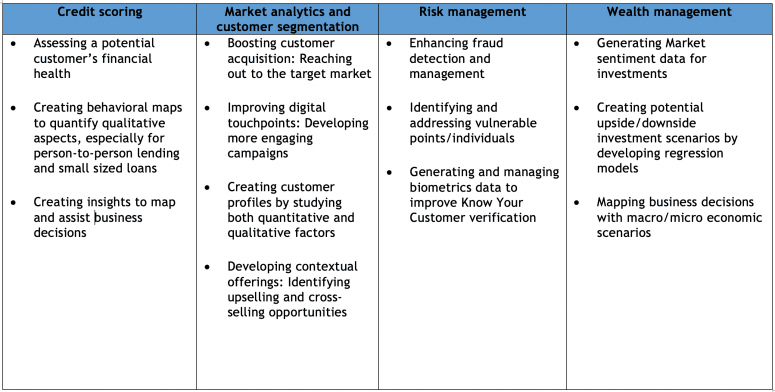

Data and analytics can allow fintechs to combine innovative business models and technology to enhance financial services. Fintechs, owing to the highly digital nature of their work and the burgeoning mobile access of their customers, can access large pools of customer information as valuable data points. Their ability to harness these data points to gain insights and drive business decisions can help them outrun their competitors. To that end, data analysis applications can be used to generate insights for diverse elements of fintech business models. Here are a few areas in which data analytics can play a critical role.

Some early adopters among fintechs have already made use of their organizational data to gain a competitive edge. Zest AI, a U.S.-based technology firm, uses machine learning to accurately predict a borrower’s ability to repay. Microcred (rebranded as Baobab) offers financial services to unbanked people in Africa by doing consumer analysis locally using cloud business intelligence. And Coverfox, an Indian fintech, uses insights derived from AI algorithms to allow users to compare and choose from a range of plans across top insurance companies.

MSC, as a partner of IIM Ahmedabad’s CIIE.CO’s Financial Inclusion Lab, has helped fintechs grow their businesses through capacity building and technical assistance. Our data domain has been working alongside partnering fintechs to build their data strategies, and to integrate analytics in their business decision processes. Based on our experiences so far, we see that many fintechs fail to fully embrace the vast potential of data. The prevailing wisdom is to keep heads down, maintain the status quo and rely on a gut feeling about the market – often driven by qualitative data and anecdotal information – in order to dedicate maximum time to managing the growth of the business. However, while this strategy may yield limited results and generate short-term tactical gains, it is inherently conservative and rarely leads to significant and sustainable growth.

The three stages of a coherent data strategy

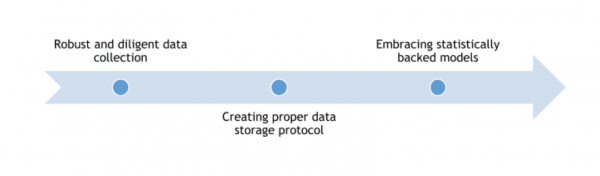

Our experience working with fintechs indicates that they need to take a bolder approach, embarking upon a journey of adopting data-driven ways of doing business. We can divide the journey into three different stages.

These three stages to creating a coherent data strategy consist of:

Robust and diligent data collection: For fintechs to leverage their organizational data, the first step is stringent data collection. This requires robust processes and quality checks to screen for missing or false information.

Creating proper data storage protocol: Once data collection has started, fintechs must implement effective standard operating practices regarding data storage. Maintaining a central database of all existing organizational data helps to ensure data privacy, and also allows fintechs to easily “slice and dice” the data for use in different business objectives.

Embracing statistically backed models: The end objective of this entire exercise is to use data to assist in business decision making. Hence, it is imperative that organizations use robust and accurate data modelling methods to help develop actionable insights.

Incorporating these three stages into a workable data strategy can be easier said than done. Quite a few fintechs use data primarily to monitor operations and track growth. The idea of converting data into insights to inform strategic business decisions is not clear to them. Similarly, fintechs with low understanding of data quality and completeness also suffer from under-utilization of data. This lack of understanding often leads them to collect and store data in non-analyzable formats, or to fail to integrate their different datasets to drive maximum potential. And even fintechs with a well-developed data strategy often struggle to move beyond descriptive analysis and delve into predictive or prescriptive analytics to guide their broader business strategy.

MSC’s work with our fintech clients has illustrated both the challenges these companies face in this journey, and the benefits they can obtain. For instance, we helped one fintech revise their credit scoring methodology by removing 75% of their parameters (which were redundant) to zero in on just 13 of them, while adding some important ones that they had overlooked. This made their credit scoring model robust, and reduced the overall cost of data collection and customer acquisition.

Another client was providing a blockchain platform for chit funds, and they wanted to use data to examine their customer retention. Though this fintech had a data strategy in place, the team was not integrating the different datasets to draw meaningful conclusions about their business processes. After a deep-dive diagnosis, MSC used unsupervised learning methods to develop a robust customer segmentation model for them. We also worked on integrating their data from segregated systems, including customer and chit fund payment details, to conduct this analysis for them.

Some fintechs are data-savvy and understand the value of their data, but lack the organizational prowess to leverage it to drive business decisions. MSC worked with one such fintech, which provides last-mile delivery to rural customers. We developed a decision tree model to identify determinants for high performance among its staff, to bolster its recruitment strategy. We also performed market basket analysis on their sales data to identify product combinations for cross-selling, thus strengthening their sales strategy.

These experiences have generated three key realizations:

- Data as a key driver of competitive advantage in business is here to stay, and the sooner players adopt it, the better they can run their businesses.

- Data can support all business-related decisions, ranging from customer acquisition to risk assessment and employee recruitment.

- Fintechs need to assess their current data practices, identify any shortcomings, and build a holistic data strategy to support their business growth.

The potential of data cannot be ignored in today’s world. Organizations that quickly adapt to this new reality will not only ensure their survival, they will flourish and continue to grow. Hence, it is imperative that fintechs understand the value of data collection, storage and analysis, to enable them to leverage this invaluable tool in the near future.

This blog was also published on Next Billion on 16 December 2020.

The role of social networks and digital payments within the microenterprise environment has been changing rapidly across the globe. The ongoing shift to digital consumerism has had a significant impact on the way micro-enterprises operate, forcing them to find new and better ways to engage with their customers and cater to their demands. Microenterprises no longer consider digital payments purely transactional. They are now necessary to improve customer engagement, meet consumers’ expectations, and reduce operating costs.

The role of social networks and digital payments within the microenterprise environment has been changing rapidly across the globe. The ongoing shift to digital consumerism has had a significant impact on the way micro-enterprises operate, forcing them to find new and better ways to engage with their customers and cater to their demands. Microenterprises no longer consider digital payments purely transactional. They are now necessary to improve customer engagement, meet consumers’ expectations, and reduce operating costs. The outreach of social media and the convenience of digital payments helped Huong ensure business continuity in times of crisis.

The outreach of social media and the convenience of digital payments helped Huong ensure business continuity in times of crisis.

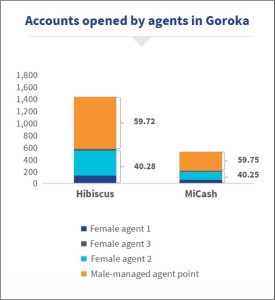

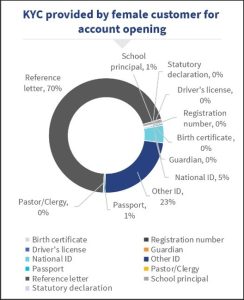

Other than the strategic decision to launch the Hibiscus account to target women customers, MiBank made two critical changes to its product offerings in Goroka. These changes affected women more than men:

Other than the strategic decision to launch the Hibiscus account to target women customers, MiBank made two critical changes to its product offerings in Goroka. These changes affected women more than men: