India’s journey of financial inclusion has been remarkable. In just a decade, more than 571 million Jan Dhan accounts have been opened, and digital public infrastructure, from UPI to Aadhaar, has reshaped how households access money, insurance, and government benefits. For millions of low-income families, women, and migrant workers, the formal financial system is finally within reach.

Yet beneath this progress lies a quieter, persistent challenge. Financial inclusion does not end with access alone; it also depends on protection, trust, and timely support when things go wrong. For many consumers, especially in rural India, grievance redress remains difficult, confusing, and unreliable. Take Rani, a daily wage worker from Uttar Pradesh, who learned this the hard way. When a failed PI transaction deducted money from her account, she made repeated visits to her bank branch. Each visit cost her a day’s wages, only to be asked for new documents every time. “I do not know if anyone will solve my problem,” she lamented. Her experience reflects the reality of millions who struggle to reach equitable financial services. While they have access, the system fails to solve their problems.

India’s vision of financial inclusion acknowledges this gap. The National Strategy for Financial Inclusion (NSFI 2025-30) emphasizes that inclusion can only be sustained when consumers have access to simple, responsive, and technology-enabled grievance and redress mechanisms. However, inclusivity remains a distant dream for many low-income users today.

What MSC’s research uncovered

MSC conducted a study across nine states to understand how low- and moderate-income (LMI) consumers navigate grievance and redress mechanisms. We used a stratified sampling approach that covered 443 LMI respondents who had registered a grievance with a regulated financial entity. Through this study, we examined their awareness, registration behavior, follow-up patterns, and resolution experiences. Our study revealed important patterns and persistent gaps that form the evidence base for the insights shared in this blog. The following section outlines key insights. Discover the detailed methodology and findings in our full study here.

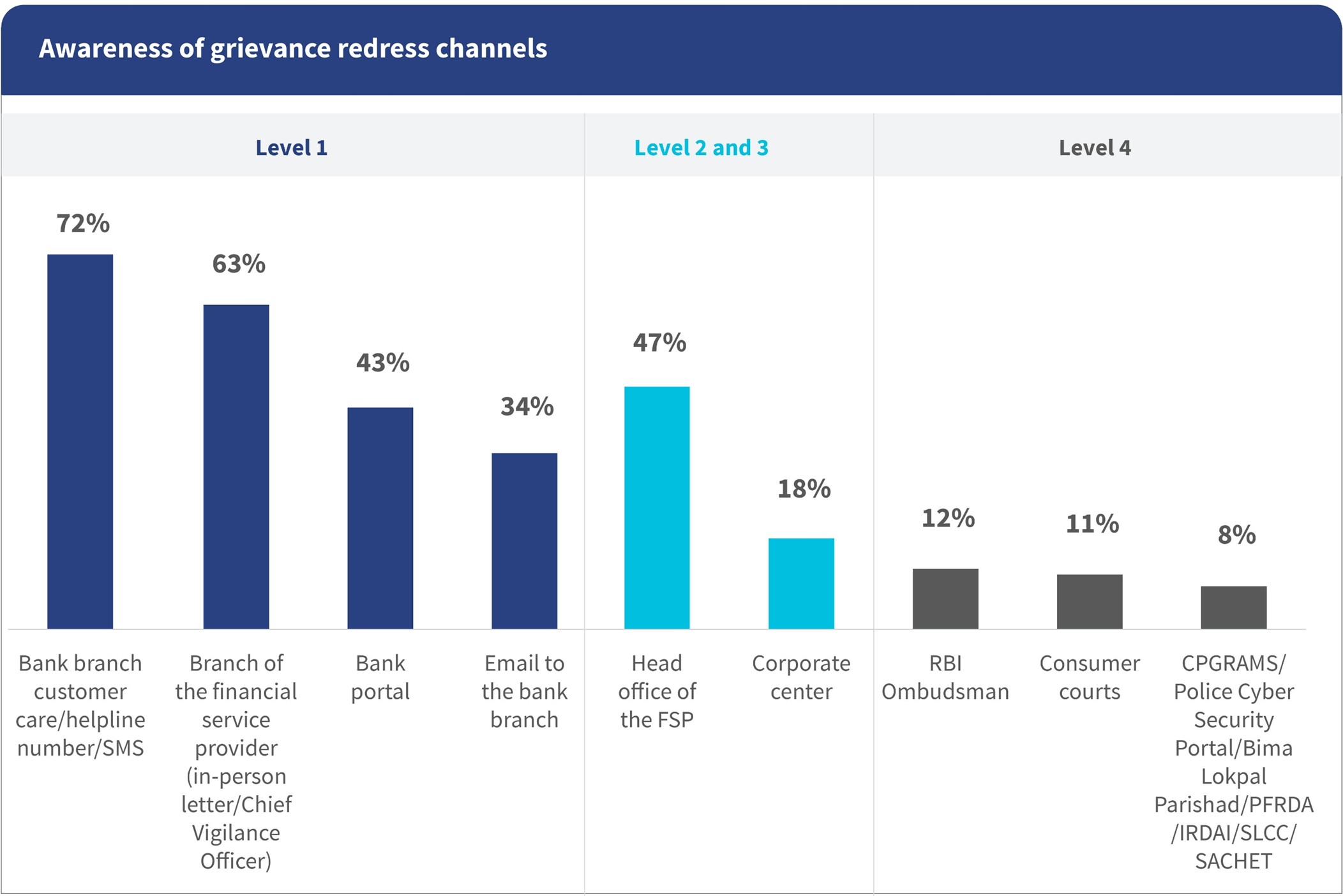

Awareness remains uneven and heavily dependent on informal channels

Most respondents knew about basic grievance channels. 73% of them were aware of helpline numbers, and 63% knew they could approach their local bank branch. However, awareness of digital or formal channels lagged significantly. Only 43% of respondents knew of online grievance portals, and just 34% were aware of email-based channels. Although financial service providers (FSPs) are expected to educate consumers, only one out of five respondents reported that they had learned about grievance and redress mechanisms from the institution itself. In contrast, 69% of respondents reported word of mouth, 55% reported internet search, and 53% reported social media as the primary sources of information. This leaves consumers vulnerable to misinformation and unsure about how to escalate their complaints effectively.

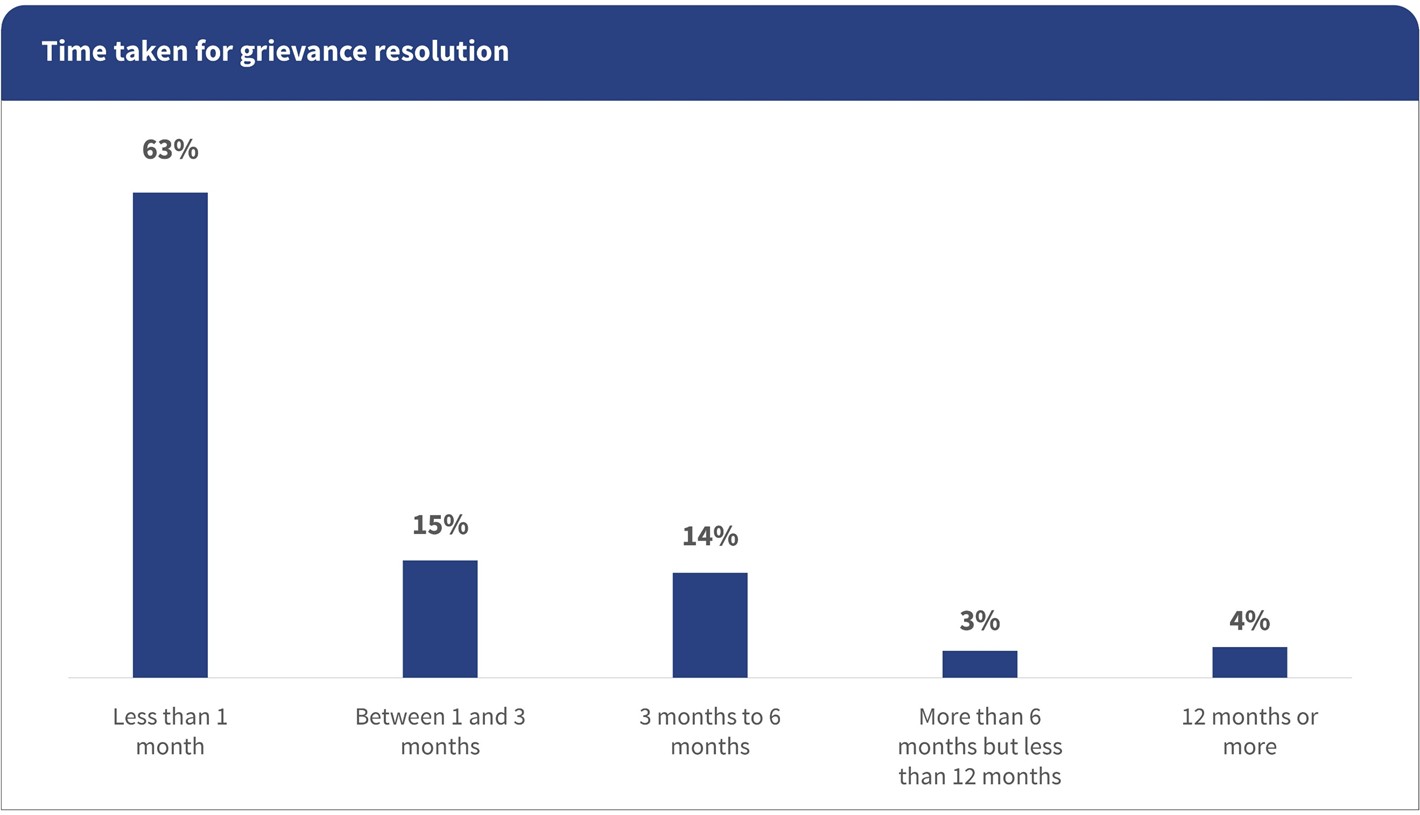

Resolution is slow, inconsistent, and often incomplete

Among all registered grievances, only 59% were fully resolved. Another 25% were partially resolved, while 16% remained unresolved, often for months. For many, delays were significant. 37% of cases took longer than a month to resolve. A farmer in Maharashtra described a harrowing experience with a pending crop insurance claim. He said, “I kept calling the helpline, but each time they asked me to wait for 15 days. It has been months now.” Such delays erode trust and force consumers to engage in repeated follow-ups.

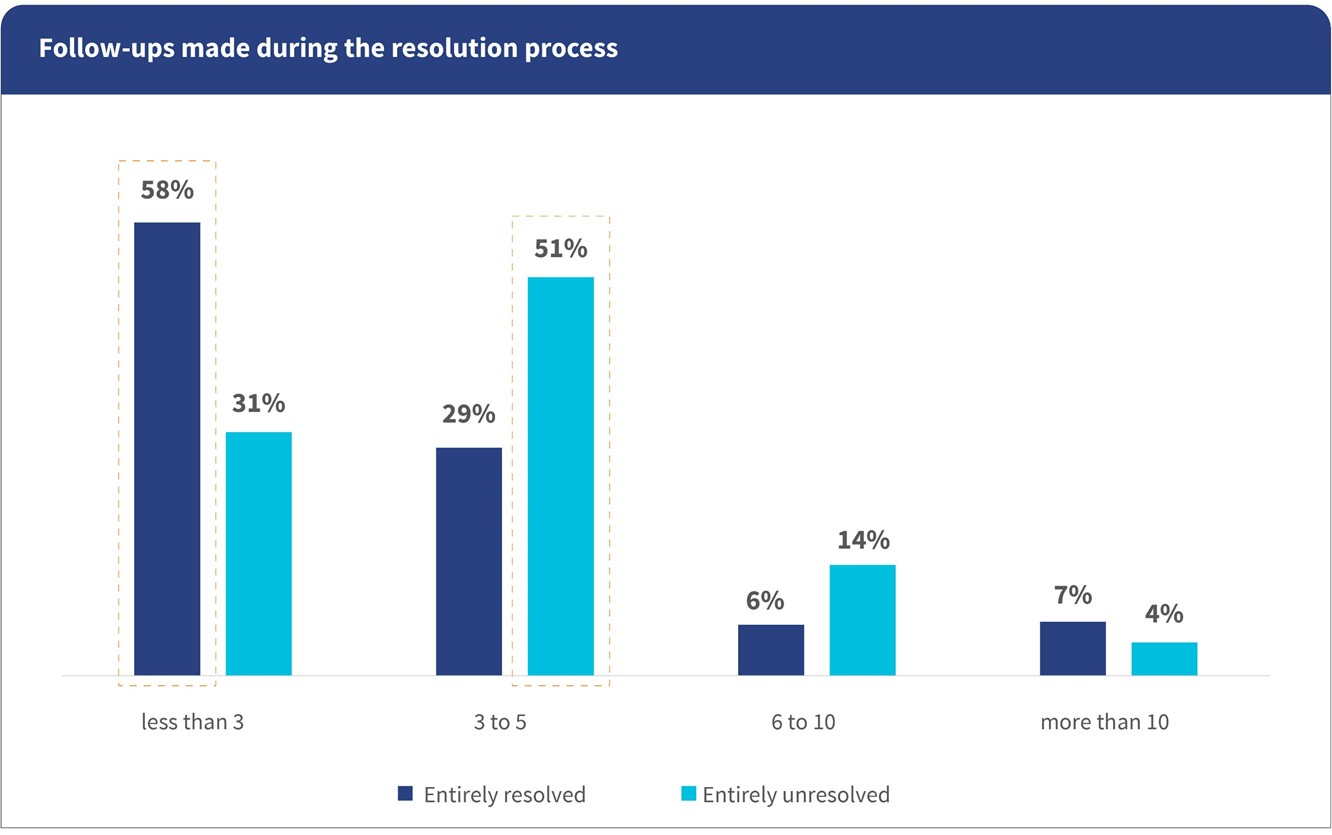

Persistence, not system efficiency, drives outcomes

Consumers’ grievances move forward largely because they continue to follow up consistently. Nearly 40% had to follow up three to five times, while 14% followed up more than six times.

The process often depends on individuals rather than institutional systems. More than half of respondents credited branch managers or staff to help them resolve their issue, while 49% said customer care agents played a major role. The system’s design does not work proactively. Resolution depends on whether a sympathetic employee chooses to support the customer. This makes outcomes arbitrary and inequitable.

Women face layered, gender-specific barriers

Women face layered, gender-specific barriers

– Women experience greater hesitation and lower confidence when they navigate grievance and redress mechanisms.

– 22% of women were afraid to interact with officials, compared to 18% of men.

– Only 57% of women’s grievances were resolved within a month, compared to 71% for men.

– Only 7% of women respondents were aware of channels, such as the RBI Ombudsman, for grievance and redress.

As a result, women often accept partial resolutions just to end the exhausting, time-consuming process. “In the end, I had to accept whatever help they offered. It was taking too long,” shared a woman from Odisha. These stories reveal a concerning pattern. They highlight a system where grievance redress relies on individual persistence, personal favors, and local goodwill, rather than structured and efficient mechanisms.

Why does this matter?

Financial inclusion cannot thrive without trust. When problems go unresolved, or grievance and redress mechanisms feel slow, confusing, or intimidating, consumers withdraw from digital channels, mobile banking, and sometimes from formal finance altogether. This disengagement harms consumers, reduces usage for providers, increases reputational and operational risks, and signals systemic weaknesses to regulators. A strong, transparent, and timely grievance and redress mechanism is therefore not a mere service feature. It is essential infrastructure that protects users, sustains confidence, and strengthens the integrity of India’s financial ecosystem.

What needs to change?

MSC’s study reveals that nearly 20% of LMI users experience fraud or attempted fraud within their networks. This has a severely negative impact on usage. of the respondents moderately reduced their digital usage, 11% sharply reduced it, and 8% stopped using digital services altogether.

This erosion of trust mirrors the concerns highlighted in the NSFI 2025–30, which underscores that sustained financial inclusion depends on strong, technology-enabled, and user-centric grievance and redress mechanisms. Such mechanisms protect consumers and reinforce confidence in digital finance. It also highlights the need for stakeholders to take systematic actions across different categories to strengthen grievance and redress mechanisms.

Category 1: Strengthen grievance access and user inclusivity

- Integrate GRM access through Unified Mobile Application for New-age Governance (UMANG), DigiSaathi, Jan Suraksha0; enable business correspondents (BCs) or customer service centres (CSCs) or self-help groups (SHGs) to help users file complaints into the RBI’s Complaint Management System (CMS) or Centralised Public Grievance Redress and Monitoring System;

- Expand IVR, WhatsApp, or USSD grievance flows;

- Build guided DFS grievance flows on DigiSaathi and ;

- Pre-fill fraud complaints through the Digital Payments Intelligence Platforms (DPIP)

- Integrate UPI, OTP, or KYC error codes into complaint workflows.

Category 2: Improve data standardization and integration

- Create a national unified grievance taxonomy;

- Enable API-based real-time data flows;

- Create a national GRM intelligence layer that will integrate the CPGRAMS, CMS, the DPIP, the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), and the State Level Bankers’ Committee (SLBC) dashboards.

Category 3: Enhance grievance resolution efficiency and timeliness

- Enable digital workflows with CMS or CPGRAMS; automate updates and publish monthly TAT dashboards;

- Deploy a SupTech early warning engine that will combine DPIP alerts, CPGRAMS data, CMS data (capturing grievance pendency and time elapsed since registration), and outage feeds.

Category 4: Strengthen last-mile facilitation and coordination

- Provide BC or CSC grievance apps linked to UMANG or CMS;

- Train BC agents to capture issues related to the DPIP and incentivize capture;

- Establish state GRM hubs that will integrate the SLBC, CPGRAMS, DPIP, and CMS, supported by quarterly audits.

Category 5: Build awareness, trust, and consumer protection literacy

- Integrate awareness into Jan Suraksha0, PMJDY, and SHG or CSC programs through multilingual outreach campaigns;

- Push DPIP alerts through WhatsApp or SMS;

- Embed safety nudges and create local fraud-watch cells.

A path forward that can build trust

Grievance resolution must become a frontline service, not a back-office burden. When a customer like Rani receives timely, fair support, it reinforces confidence in the system not just for her, but for her entire community.

However, our study reveals that today only , which reveals significant gaps in service experience and accountability.

Effective grievance and redress mechanisms strengthen financial inclusion as they ensure that every user is treated fairly, problems are solved transparently, and complaints are not dismissed or lost. When redress systems work, customers feel respected, protected, and empowered to remain active participants in formal finance.

Research shows that grievance redress or effective dispute resolution significantly increases users’ “continuance intention” to use mobile wallets and digital payments. Globally, studies by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) find that strong dispute-resolution systems boost consumer loyalty, reduce churn, and increase repeat transactions. For India, a strong, transparent, and accessible redressal system is not a luxury- it is foundational infrastructure. As India advances toward the NSFI 2025–30 vision, strengthening grievance redressal becomes central to deepening usage, enabling safer digital adoption, and ensuring that every financial consumer feels protected within the system. By ensuring that user grievances are fairly and promptly addressed, we not only protect consumers but also sustain long-term engagement, deepen financial inclusion, and build a resilient, trustworthy digital finance ecosystem.

Every eligible grievance should be recorded, and once registered, it must be resolved as per regulatory guidelines. With the right systems and accountability, we can ensure that every person who enters the formal financial system feels protected, respected, and empowered to stay.