The vulnerable blue-collar worker segment in the country desperately needs advocates

The blue-collar industry in India has seen rising demand, especially with the advent of the digital economy and the subsequent increase in demand for at-home services. Companies in the delivery space have shown little respect to their delivery partners by introducing gigs like 10-minute delivery services, which puts their lives at risk as they are pushed to race through traffic to complete assignments on time. Could there be a better time when we need advocates for this vulnerable employee segment of our country?

Fresh graduates in India lack employability skills in the tertiary sector, while agricultural employment continues to plummet. As a result, many continue to join India’s sizeable blue- and grey-collar workforce.

Fresh graduates in India lack employability skills in the tertiary sector, while agricultural employment continues to plummet. As a result, many continue to join India’s sizeable blue- and grey-collar workforce.

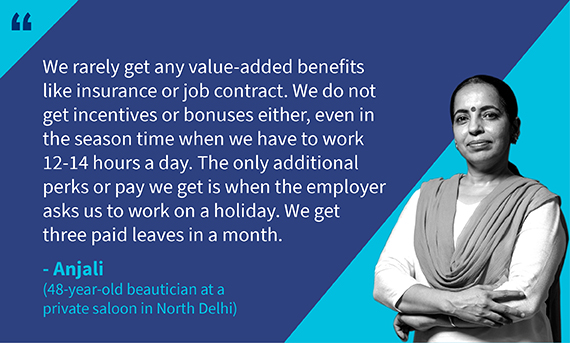

India currently has more than 250 million blue-collar workers like Anjali who earn less than INR 15,000 (USD 194) per month and likely lack fair working conditions or secure employment. Furthermore, most employers do not give them even essential benefits, such as medical insurance and pension, which are crucial to their health and security. Studies suggest that providing these benefits also improves performance and cuts down attrition rates.

Anjali’s cousin Megha, who works as a receptionist at a hotel chain in Delhi, gets value-added benefits like medical insurance. When Megha was hospitalized in a road accident, the insurance company paid all the expenses. Megha’s savings were not affected, nor did she have to take a loan to pay her hospital bills. Now, Anjali also wants to work for an employer that offers such essential benefits.

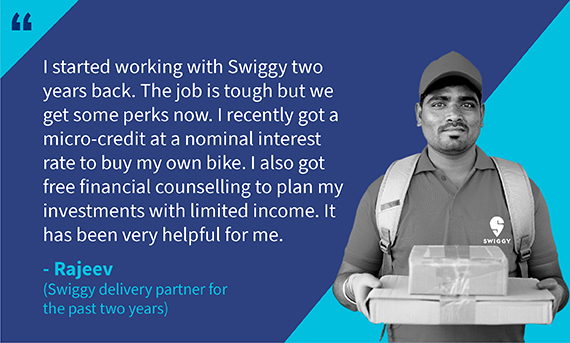

The FinTech Entitled recognized such needs of people like Anjali early on. Our previous blog charts how the founders work to make a difference in the lives of the fast emerging blue-collar and gig worker segment. With innovative product bundles, Entitled has reached out to about 300,000 users and served their wellness needs through its bouquet of products and services to improve customers’ financial health.

A complex problem needs a strong vision

Empathy, passion, and business acumen drove founders Anshul, Krishna, and Arpan to set up Entitled to address the challenges in the daily lives of blue-collared workers. The startup now provides financial wellness solutions for the segment—a critical but often missing piece in the puzzle of employees’ personal and financial health. It handholds its employee beneficiaries by providing financial consultation alongside other benefits from its product suite. Entitled happily responds to more than 20,000 inquiries for different financial service availability each month.

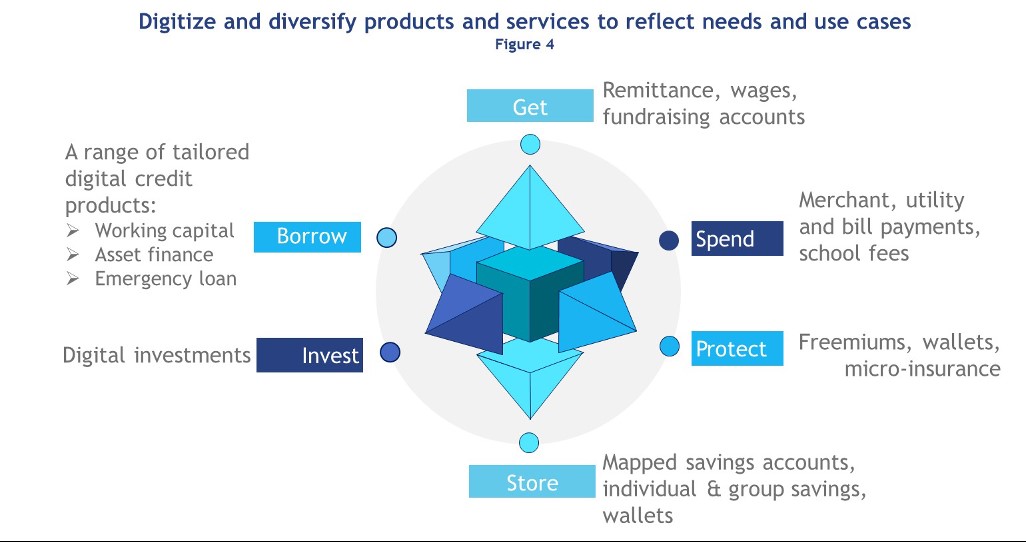

Further, the startup fulfills the recurring loan needs of 30% of its users who need more than one loan a year. The founders believe that credit alone will not build the financial resilience of low-and-middle-income (LMI) households. Savings and insurance are also essential to help these households absorb financial shocks. As Anshul remarks, “We look beyond credit as it alone cannot pull these households out of the poverty trap. It is time the blue-collar segment also receives white-collar benefits to enable their financial well-being.”

It is not about credit; it is about financial health

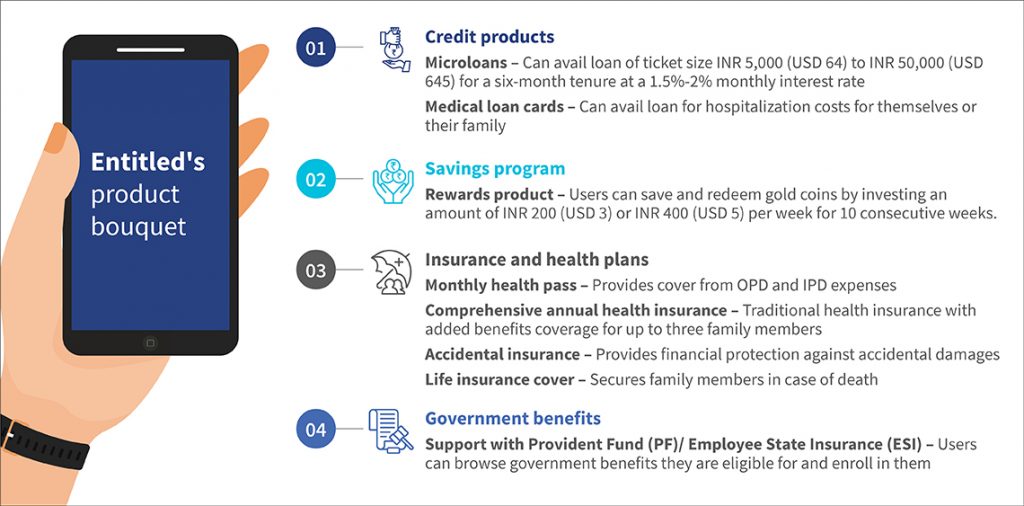

Entitled expands the horizons of employee engagement by stitching together diversified products and services, including government benefits, into a wellness suite. 25% of the Entitled users avail of insurance and health schemes, while the startup helped 10% of users enroll for relevant government schemes. This is a stepping stone in the startup journey to empower financial wellness for users by building on risk mitigation products. Further, Entitled has built a comprehensive product that combines access to health financing, teleconsultations, and discount on outpatient expenses across the primary healthcare network. The Entitled user base has hugely subscribed to the bundled financing product. While more than 80% of customers usually avail of health loans, 95% sought home loans during COVID-19 as a coping mechanism. Entitled now wants to evolve into a platform where workers can avail all these services. It is designing alternate channels where users can effectively learn about the services.

Entitled offers a wide bouquet of services for the blue-collar worker segment. After a consultation call, it provides the services at nominal charges to interested beneficiaries. Entitled’s employer partners often offer a few selected services to their employees at a subsidized cost as a part of their contract. After an employee is onboarded onto the Entitled platform, they can navigate through Entitled’s services and avail literacy and counselling sessions they may need.

Entitled also plans to launch a rewards and recognition program for workers, customized to the requirements of its partners.

A safe space for the blue-collar worker segment to achieve financial wellness

Entitled sees itself as a one-stop solution for its user’s problems. Its mantra is, “where there is a problem to be solved for blue-collar workers, we ideate.” The startup wants to deliver innovative solutions in an accessible manner. Entitled relies on user data to strengthen its understanding of the demand gaps for blue-collar workers and intends to reach five million beneficiaries by 2025.

Since its inception, Entitled has directly provided benefits like medical consultancy, insurance, and credit to about 100,000 active users through employer partners. Around 40% of Entitled’s customers currently use financial services for the first time. This narrates the responsibility of startups like Entitled in giving their customers an informed first-time user experience. The startup intends to enhance its channel delivery to onboard another 5 million beneficiaries through the existing B2B2C model and further innovate the B2C customer acquisition model. The founders are building effective communication and service delivery channels to this effect.

Channel enhancement for improved user experience

Entitled acknowledges it is essential to reach workers through their employers and an interface they can trust. At present, Entitled communicates with its beneficiaries using a WhatsApp chatbot. MSC is helping the startup explore and evaluate different interfaces for service distribution channels to make the experience convenient for users. Entitled understands its customers well and has been working on assembling the pieces of the wellness puzzle.

Entitled acknowledges it is essential to reach workers through their employers and an interface they can trust. At present, Entitled communicates with its beneficiaries using a WhatsApp chatbot. MSC is helping the startup explore and evaluate different interfaces for service distribution channels to make the experience convenient for users. Entitled understands its customers well and has been working on assembling the pieces of the wellness puzzle.

Employers also increasingly recognize the need to make their employees financially healthy since it directly impacts their business. Now, Entitled’s founders seek to reshape the startup into a holistic benefits platform that can ease the complex and multifaceted struggles of India’s numerous blue- and gray-collar employees.

FLYK was Apratim’s second startup. He had met Prafful while developing his first app. Prafful was drawn to startups that worked to make a social difference. Apratim and Prafful decided to build the platform together to enable meaningful change for rural customers through loan services.

FLYK was Apratim’s second startup. He had met Prafful while developing his first app. Prafful was drawn to startups that worked to make a social difference. Apratim and Prafful decided to build the platform together to enable meaningful change for rural customers through loan services.

With 8,000+ successful downloads, FLYK is taking its first steps toward success. The startup has processed about 1,508 loans until April 2022 and envisions expanding rapidly. Out of 635 users, FLYK has an 86% retention rate on its platform.

With 8,000+ successful downloads, FLYK is taking its first steps toward success. The startup has processed about 1,508 loans until April 2022 and envisions expanding rapidly. Out of 635 users, FLYK has an 86% retention rate on its platform.

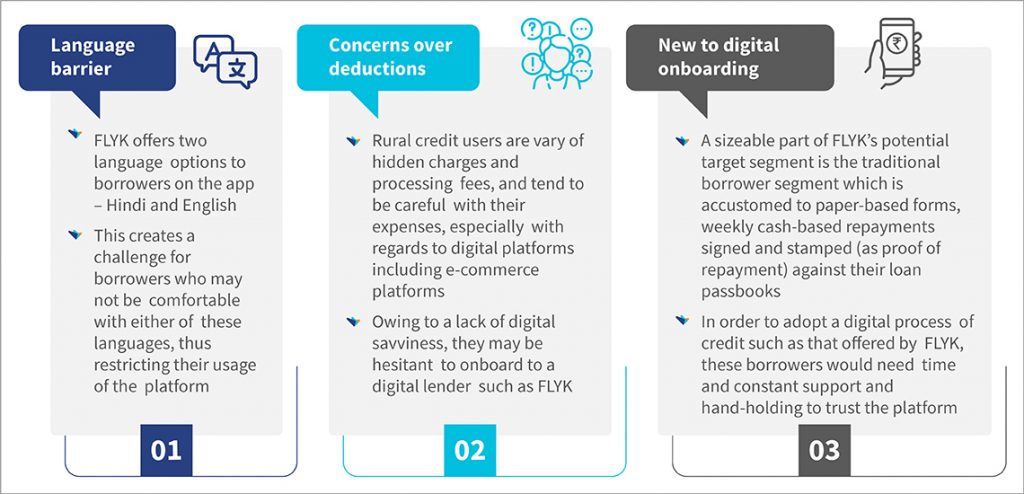

Customer challenges to adopting FLYK

Customer challenges to adopting FLYK