India announced a nationwide lockdown on 24th March, 2020 to deal with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The initial days after the lockdown were disruptive for tech-based delivery platforms, as the government instructed these platforms to restrict their deliveries to essential goods and services alone. These platforms became increasingly flooded with orders as government directives restricted the movement of citizens. A rushed decision and lack of clarity on the implementation guidelines resulted in on-ground confusion, causing frustrating delays in the delivery of goods.

With customers unwilling and in many places unable to go out and shop, the opportunity for tech platforms was there for the taking. Eager not to miss out, some agile tech platforms quickly formed innovative partnerships to ensure deliveries and minimize the impact of the lockdown on their businesses. BigBasket, a grocery delivery platform, which is classified as an essential service, forged a partnership with Uber to complement its delivery fleet. Uber entered the arrangement as cabs were deemed a non-essential service, and therefore had an idle fleet available to deploy. Similarly, the grocery delivery platform Grofers hired 2,500 people to continue delivering services from affiliated industries and partner companies that had to shut down.

The effect of COVID-19 on platform-based gig work

The gig workers across tech platforms who offer rideshare, personal and home care, and delivery services have not been so lucky. Initially, the possibility of no work and therefore no income during the lockdown forced many of them to travel back to their villages. Many such workers and their families have had to walk hundreds of kilometers to do so. The ones who continued to work faced the occasional wrath of the police and local authorities.

The driver-partners of ride-share platforms Uber and Ola have been hit the worst. Even as they face mounting losses in income, they are under pressure to repay their car loan installments. Meanwhile, the need for strict hygiene and safety measures meant that food delivery continued to operate at lower than normal levels. Researchers Simiran Lalvani and Bhavani Seetharaman report from their self-administered survey of food delivery workers that the proportion of delivery partners who would earlier receive 16-20 orders per day went down from 30.9% to 7.2% post the lockdown.

Platforms support to the gig-workers

Urban Company, a tech platform for home-based services, extended interest-free loans, health insurance of up to INR 25,000 (~USD 325), and income protection to its partners if diagnosed with COVID-19. Similarly, Ola has been offering interest-free microloans of up to INR 3,600 (~USD 50) and has waived lease rentals for driver-partners. It has also offered health insurance of up to INR 30,000 (USD 390) for all driver-partners and their spouses.

Despite the usual gaps between promises and actual implementation, the measures that these platforms have put in place are steps in the right direction as they consider the health and economic security of the gig-workers. However, one may wonder why the platforms hesitated to implement such measures before the COVID-19 outbreak. Gig workers have continued to face challenges around the lack of transparency in remuneration structure and payout, absence of safety nets, and long working hours, all of which have had an impact on their health and economic security.

These problems are not new and definitely cannot be attributed to COVID-19. These issues have been talked about for some time now. The COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing crisis should lead to more concrete action to develop a social security program for gig workers.

Designing a social security program for gig workers for the future

In India, 72% of the labor force or around 303 million people work in the informal sector and lack income protection or other safety nets in times of crisis. The country has around 275 million people who live under USD 1.25 per day and another 300 million people who cannot withstand a sudden shock like the COVID-19 crisis. The pandemic and the ensuing lockdown have resulted in the labor force participation rate (LPR) contracting from 43% in late 2019 to 36% by 5th April 2020. The LPR declined by 3% between 29th March and 5th April alone, which hints at the enormous impact of the pandemic on the economy.

Given the size of the informal workforce and their vulnerability, particularly in times of crisis, designing social security programs for gig workers who comprise an emerging subset of the informal workforce could be a good starting point.

The role of technology and the formal financial system in creating a social security net

Tech platform-based gig workers are better equipped than others are in the informal sector in terms of their access to technology and the use of formal financial services. They receive their payments in bank accounts and know how to use smartphones. However, like other informal workers, their incomes vary according to the total time worked, availability of orders on the platforms, and seasonality of demand and migration patterns. Gig workers also alternate between one or two service providers to take advantage of any differential incentives on offer.

These attributes suggest that gig workers need a model of social security distinct from the ones prevalent for formal sector workers, such as the Employment Provident Fund Organization, or the Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maan-Dhan (PMSYM), which targets informal workers in general. The variability, temporary nature, and seasonality of demand for gig work require careful design of the model to ensure wider adoption.

With the advancement of technology, the sharing and portability of social security accounts across multiple platforms no longer pose as barriers. Improvements in payments technologies enable low-value transactions at low costs like the Unified Payments Interface, while a million-strong physical cash-in cash-out network can help the design of scalable social security systems for gig workers.

The role of the government

In their book In Service of the Republic, Ajay Shah and Vijay Kelkar point to the limited capacity of the Indian state and caution against expecting too much from the government. The government has diminished capacity to design and implement large-scale social security programs for gig workers. This will be truer still in the aftermath of this crisis.

Shah and Kelkar suggest that the ideal role of the government should be on the “regulatory” and “financing” aspects of the system. One of the criticisms of the several social security programs that the Indian government runs is that these are fragmented and limited in their coverage of informal workers. Therefore, the government should focus on creating a universal social security system with the participation of the private sector to include all informal workers.

The government, therefore, should frame rules to implement the program and provide a platform for dialog among stakeholders—including private sector players and labor unions. It should also determine the size and scale of the subsidy. This entails committing its contribution to social security programs to maintain a minimum social security floor and complement the contribution from individuals or employers, or both.

In conclusion, as the lockdown lifts slowly across India, the immediate focus will be to kick-start the economy and push the participation rates of the labor force up to pre-COVID-19 levels. State and national governments will continue to remain stretched from the emergency spending during the crisis. Therefore, the role of the platform economy will be crucial to provide economic opportunities for informal workers.

This crisis offers tremendous opportunities to derive valuable lessons. The absence of a well-functioning social security system has aggravated the sheer scale and impact of the crisis on the livelihoods of the bottom 40% of the population. Not only is gig work likely to be a key component of India’s economy moving forward, but it also provides unique opportunities to provide embedded social safety nets. India could, and indeed should, pioneer this.

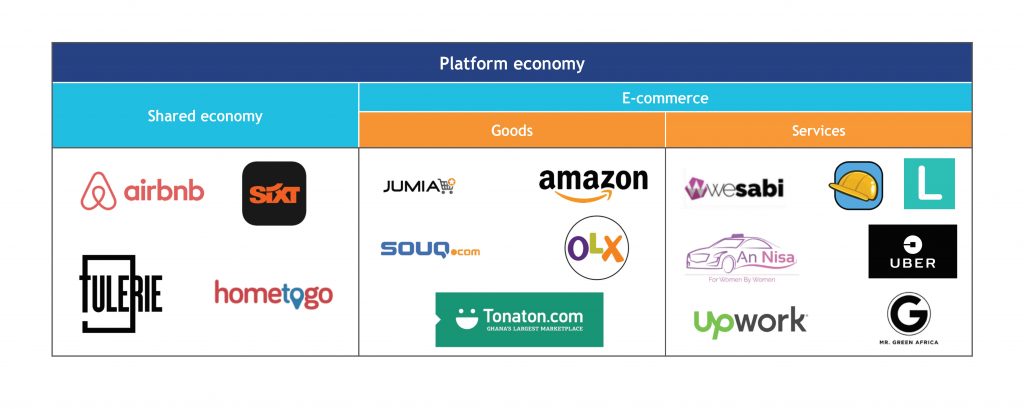

Platform economy across the globe

Platform economy across the globe