The early part of 2020 has been a nightmare for India. The rising cases of COVID-19, countrywide lockdowns, and fear of contracting the virus have taken a toll on the physical, mental, and economic well-being of the people. Until the COVID-19 struck, the Indian FinTech industry was growing rapidly. It was rolling out the products and services based on gaps in the existing financial services and attracted private capital at an unprecedented pace. In this report, we will assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the FinTech ecosystem of India.

Blog

Analysis of India’s payment system indicators in Q2 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has acted as a second wave of behavioral shift after the demonetization in 2016, which has pushed many users to adopt digital payments as they seek convenience and adhere to safety precautions. We see an opportunity to go digital during these unprecedented times.

MSC’s analysis of select payments system indicators in India during Q2 2020 indicates that the payment systems on the country are dependable and durable and continue to command a high level of confidence from the mass market. The study covers five categories of payment system indicators—currency with the public (cash), contactless payments (UPI, BBPS, BAP), Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS), card-based payments and transactions (debit cards, credit cards, RuPay debit cards), and remittances and money transfers (RTGS, NEFT, IMPS, APBS).

The study highlights that despite the lockdowns, the demand for cash as a “safe asset” continues to rise, particularly among low- and moderate-income communities as they prepare to weather difficult days ahead. Contactless payments, such as the UPI, BBPS, and BAP, have made a near v-shaped recovery in Q2 2020 and are back to pre-COVID-19 levels. Payments systems, such as AePS and BBPS, have been stress tested with double their historical average. Read more here.

Philippines: Impact of COVID-19 on Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)

The COVID-19 pandemic and consequent restrictions to curb its spread have taken a toll on MSMEs in the Philippines. This report highlights the nature and extent of the impact of COVID-19 on the cash-flows, business operations, and supply chains of these MSMEs. It delves deeper into the coping strategies they adopted to mitigate the effects of this disruption. The report also provides recommendations for policymakers and financial service providers to help accelerate the recovery of the MSME sector.

Impact of COVID-19 on FinTechs: Indonesia report

FinTechs have been key to Indonesia’s booming digital economy, which is estimated to be worth USD 133 billion by the end of 2025. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has turned out to be a mixed bag for the FinTech community in Indonesia. While the pandemic has been a blessing in disguise for few FinTechs, most early-stage FinTech start-ups have been pushed to the brink as they scramble to extend their runways.

This report takes a closer look at the impact of the pandemic on the operations, revenues, and coping strategy of FinTechs in Indonesia. The report also explores the sentiments of investors and the impact of government policies on the development of the FinTech sector in the country. We also provide recommendations for the concerned stakeholders to help the FinTech community recover from the current crisis.

Revitalizing Agriculture market systems

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed our unpreparedness to deal with food supply in the event of a global pandemic. With fragmented supply chains, weak market linkages, and high post-harvest losses characterizing agriculture supply chains in most developing countries, the pandemic has further strained the agri-market systems. On one hand, the public expenditure in the form of subsidies and agri-market stabilization funds is showing sub-optimal results on strengthening the agri-market systems, the producers, especially smallholder farmers are suffering losses due to inability to access agriculture inputs and a reliable market for their produce. While governments have responded with short-term measures to deal with the crisis, it calls for a systemic assessment coupled with policy and regulatory support to address the situation having a longer-term perspective to revitalize agriculture market systems. The short video highlights the need for market systems’ readiness assessment and how it can be implemented.

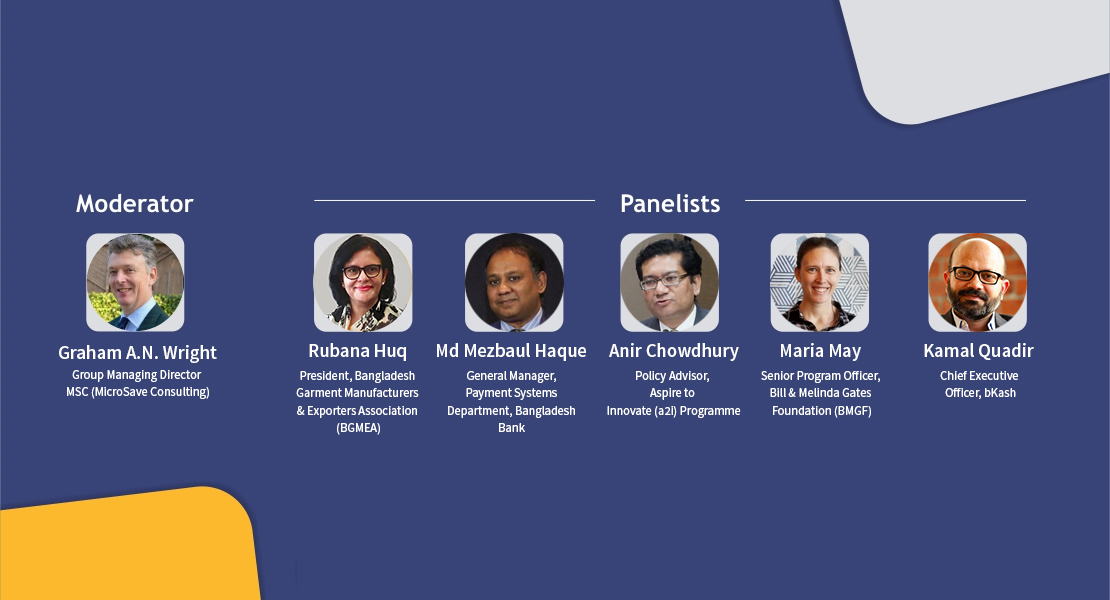

Highlights of I2L webinar Episode 2 on “Successful cash support payments to the most vulnerable: Lessons from Bangladesh”

In this webinar, a power-packed panel discussed Bangladesh’s journey to enable this scale of financial inclusion, the challenges in designing and operationalizing the payment infrastructure, and the lessons from on-ground implementation. The key themes for discussion were:

- Role of digital financial infrastructure in situations such as COVID-19 pandemic

- Establishing Bangladesh’s digital financial services infrastructure

- Practical insights from rolling out the cash support transfers, covering both CICO agents and local governance infrastructure

- What might other countries learn from Bangladesh?

* 0:00 – 1:33 – Graham Wright presents the welcome note, introduces the panelists and the agenda, and speaks about the role of digital financial infrastructure in situations like COVID-19 and beyond

* 1:34 – 4:40 – Graham Wright highlights Bangladesh’s achievements in its digital financial infrastructure. He states four recent achievements, namely the readymade garments sector, Social Safety Net, Cash Assistance, Union Digital Center. He introduces the first topic of the day: The role of digital financial infrastructure in situations like the COVID-19 pandemic

* 5:18 – 9:51 – Anir Chowdhury, Policy Advisor of the A2I program responds to Question 1 – a2i has pioneered the process of digitization of public services in Bangladesh. He tackles two questions: How would you rate the adoption and comfort of the poor who use digital services? Do you feel the digital divide is closing or are there still miles to go?

* 10:27 – 14:30– Mezbaul Haque, GM, Bangladesh Bank responds to the second question: Customer onboarding and verification has been a major challenge in markets like Bangladesh. What has Bangladesh done to ensure simplified onboarding while at the same time protecting the privacy of the customer?

* 15:41 – 23:48 – Kamal Quadir, CEO bKash, responds to Question 3: Bangladesh’s MFS ecosystem rides on partnerships with telecommunications companies. How do the telecom partners view MFS today compared to when you had started? Can any steps or initiatives further strengthen the coalition?

* 25:13 – 31:00 – Rubana Huq, President BGMEA, responds to Question 4: The Government of Bangladesh announced the requirement for readymade garments workers to receive wages through MFS on 4th April. Creating 2.5 million formal financial accounts through MFS in less than 30 days is in itself a humongous task. How would you prepare to ensure the workers adopt digital payments in such a short time? How did factories manage customer protection norms, and ensure the right worker received the right amount right on time?

* 32:09 – 37:42 – Maria May, Senior Program Officer, The BMGF, responds to Question 5: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s support in the journey of digital Bangladesh so far has been invaluable. How ready are people in Bangladesh, especially the vulnerable communities, to embrace digital financial services? What special measures need to be in place to enable women to use them?

* 37:51 – 38:32 – Graham Wright presents highlights from the G2P programs, Education allowance (PESP), SSN, and Cash Assistance programs, among others, bringing in similar examples from India and Kenya. He introduces the second topic: Insights from G2P program

* 38:57 – 47:25 – Anir Chowdhury responds to Question 6: Under your leadership, a2i was involved with one of the largest cash assistance programs ever in Bangladesh using MFS channels. How did you manage the complex issues of beneficiary selection, enrollment, disbursement, and fraud management?

* 48:26 – 53:40 – Kamal Quadir responds to Question 7: bKash has been a major partner in enabling G2P payments in Bangladesh—starting from various education stipends to the cash assistance programs. It is complex to make such mass payouts a success. How did you balance the priorities like ensuring network and tech support, agent support, customer onboarding, while managing liquidity during this pandemic?

* 54:35 – 58:39 – Rubana Huq responds to Question 8: RMG industry is not new to digital payments. Many initiatives have been to foster the adoption of digital payments in the garments industry. What hinders this adoption? What can be done to further accelerate the use of digital financial services by the industry and its workers?

* 59:24 – 1:02:01 – Mezbaul Haque responds to Question 9: Creating the right regulatory environment is essential for any major G2P programs to succeed. What is Bangladesh Bank’s approach to engaging all types of players in the ecosystem? What is the central bank’s vision for synchronizing efforts of agent banking and MFS?

* 1:02:34 – 1:08:14 – Maria May responds to Question 10: For emergency cash support transfers, which you have seen in other countries as well. What are the lessons or best practices that governments could learn? In particular, how can governments extend these payments into rural areas?

* 1:08:28 – 1:08:44 – Graham Wright shares updates that make Bangladesh an inspiration to many countries in the world and make its strides towards digital financial inclusion remarkable. He introduces topic 3: Learning from Bangladesh

* 1:08:55 – 1:09:56 – Anir Chowdhury responds to Question 11: The pandemic has driven many countries in the world to consider digitizing G2P payments. What can those countries learn from the experience of Bangladesh?

* 1:10:12 – 1:10:38 – Mezbaul Haque responds to Question 12: What would be your advice to policymakers and central bankers wanting to expand digital payments?

* 1:11:10 – 1:13:01 – Kamal Quadir responds to Question 13: bKash is synonymous with MFS in Bangladesh and is an inspiration to many aspiring DFS players around the world. One of the major strengths of bKash is its rollout and management of the largest agent network in the world. What were the major challenges in expanding to the last mile? If you had started today, would you have taken the same approach to network expansion?

* 1:13:15 – 1:14:47 – Maria May responds to Question14: You have seen and interacted with governments of various developing countries. How would you compare Bangladesh’s journey with others? What are the key lessons that countries with similar demography may take away?

* 1:14:48 – 1:15:12 – Graham Wright requests Anir Chowdhury to sum up today’s lessons for the audience and shares a note of appreciation to a2i in co-hosting the webinar

* 1:15:14 – 1:19:51 – Anir Chowdhury responds on request by Graham Wright to provide a summary to the webinar: 1. Bangladesh’s journey in G2P and way forward 2. Contribution of the digital infrastructure and ways to utilize technology 3. What Bangladesh is right and where it needs to learn more

* 1:19:54 – 1:31:52 – The panelists respond to some tricky audience questions

Question 1) Is digital capability essential to realize the full potential of digital finance service in Bangladesh?

Question 2) What do we need to do to encourage Microfinance clients to use digital payment?

Question 3) What are the changes necessary to encourage digital credit offerings in Bangladesh?

* 1:31:53 – 1:32:47 –Graham Wright presents the concluding remarks.