The Government of India (GOI) launched the(Digital India Land Records ModernisationProgramme (DILRMP) in August 2008. DILRMP aimed to develop a modern, comprehensive, and transparent land records management system, which would provide conclusive title guarantee to landowners.

Blog

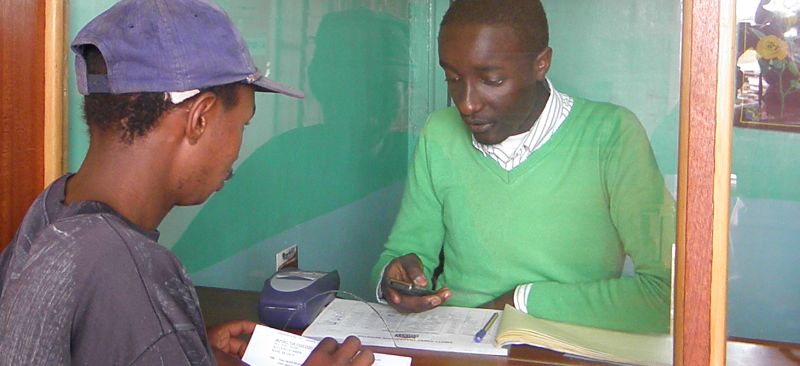

A first look at Indonesia’s emerging agent network

Digital Financial Services (DFS) emerged in Indonesia in 2007, with e-money services targeted at the middle income and affluent segments rather than the unbanked and underbanked masses. In 2014, regulators allowed banks and e-money providers[1] to use individual agents, paving the way for the emergence of agent networks. Since then, financial inclusion has become an important development goal of the Indonesian government, with DFS delivered through agents being its key driver.

MicroSave/The Helix Institute of Digital Finance conducted the first round of Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Indonesia research in 2014 when the branchless banking regulations had just been rolled out. Based on qualitative agent interviews, the research highlighted nascent attempts by providers to develop agent networks and issues related to agent selection/training and monitoring systems. In 2017, MicroSave completed the second round of research, which was a large-scale, nationally representative quantitative survey of 1,300 DFS agents. The study aimed to inform relevant DFS stakeholders on the progress and challenges of agent network development. It would also inform stakeholders on the opportunities to further expand and improve efficiency and quality of service delivery via this channel for digital financial inclusion in the country. This blog summarises the key findings of the ANA survey.

Two Service Providers Dominate the Market Presence

In three years, Indonesia has seen a rapid expansion of DFS agent networks. According to OJK data, over 400,000 DFS agents are serving over 10 million DFS accounts in the country. Despite such high growth rates, agent and customer dormancy remains high. MicroSave estimates more than 30% of DFS agents and 30%–55% of DFS accounts are dormant.[2] The agent network in the country is relatively young – 75% of agents have been in the DFS business for less than two years. Indonesia also happens to be the only ANA research country in Asia where women agents outnumber their male counterparts – 59% of DFS agents are women.

While more than 20 DFS providers currently offer DFS services, two banks – Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) and Bank BTPN account for 80% of Indonesia’s DFS agent population. With a staggering 63% market presence, BRI is more dominant in Jabodetabek (Greater Jakarta) and rural areas but has a more modest presence (44%) in urban areas outside Jabodetabek.

Agent Network is Exclusive and Non-dedicated

In line with the existing regulations, virtually all (97%) of Indonesian agents are exclusive, serving only one service provider. However, one-third (33%) of exclusive agents expressed interest in serving more than one service provider. A common motivation for mandating exclusivity is to give the regulator clarity on who is responsible for agent training and monitoring, customer grievance mechanisms, and consumer protection. This appears to be the case in Indonesia. Nearly all agents (96%) are non-dedicated, meaning DFS is an add-on to their existing line of business. Non-dedicated agents are significantly more profitable compared to their dedicated counterparts. Only one-third (38%) of dedicated agents can break even or make profits

from their DFS activity, compared to 80% of non-dedicated agents. This is understandable given that the DFS market is nascent, transaction volumes are low, and regulations mandate exclusivity.

Service Offerings are Diverse, but Account Opening is Deprioritised

Although expanding access to a bank accounts is the cornerstone of the national financial inclusion strategy, at the moment, only 28% of agents offer account registrations. A cumbersome account opening process, ineffective incentive systems, and a lack of customer DFS awareness hinder wider registration offering. Similar to markets like Pakistan and Bangladesh, Indonesia is largely an Over-The-Counter (OTC) market, where money transfer and bill payment transactions dominate. Low average cash-in values (USD 8), as opposed to money transfer (USD 30), indicate that providers have yet to devise use-cases that would compel Indonesians to keep and use the money in their digital wallets/accounts.

Transaction Levels and Profitability is the Lowest Among all ANA Countries

Indonesian agents conduct a median of four transactions per day, the lowest amongst all ANA research countries. Agents in other OTC markets, such as Pakistan (15), Bangladesh (30), and Senegal (35) transact more. Exclusivity requirements combined with the nascence of the DFS market largely explain the low transaction volumes. However, agents in the Jabodetabek area are the busiest, conducting a median of 10 daily transactions, which is a figure comparable to agents’ transaction volumes for a single provider in Pakistan. This pattern is hardly surprising since the early adopters of DFS usually live in big cities. The agents in rural and non-Jabodetabek urban areas conduct five and three median daily transactions, respectively. The low transaction volumes result in low agent profitability. The median monthly profits from the DFS business is USD 6, significantly lower than in Senegal (USD 120), Kenya (USD 77), Bangladesh (USD 57), and Pakistan (USD 43). Surprisingly, despite low profitability, half of the agents are satisfied with their earnings from the DFS business, while 91% want to remain in the business for another year.

Internal Teams from the Providers Manage the Agents

Since regulations currently prohibit partnerships with third-party agent network managers, most service providers use in-house teams to recruit, train, monitor, and supervise agents. Strategies for agents monitoring and supervision varies: larger banks with deep rural presence manage agent networks through regular bank branch staff, while other providers have appointed dedicated teams to manage their agent networks. Despite providers’ efforts, most agents reported that they are only “somewhat” satisfied with provider support services.

Three-quarters of agents reported being trained within the first three months and virtually all the agents are trained by service provider staff. Agents in the Jabodetabek areas are less likely to receive training compared to their rural and non-Jabodetabek urban counterparts. The majority of agents (67%) depend on support staff to address grievances. Only around a third of agents use WhatsApp and call centres for support. Agents receive infrequent and ad-hoc support visits from the provider staff. Nearly half of agents (43%) do not receive visits at all, which translates into low product awareness, low compliance, and inconsistent customer service. As agent networks evolve and continue to grow, the processes of recruitment, monitoring, training and liquidity management challenges will likely intensify. Allowing service providers to partner with Agent Network Managers (ANMs)/Aggregators will help to scale agent networks effectively and avoid overburdening bank staff or bloating agent network servicing teams.

What’s Next?

Agent networks in Indonesia are nascent but evolving. The recent government push to digitise payments (G2P) can propel agent networks and drive the demand for customer registrations and consequently transactions. The DFS community can complement government efforts by investing more in consumer awareness drives to further boost the uptake and usage of DFS services. The next blog in this series will highlight measures that service providers and regulators can take to stimulate the DFS market along with best-practice from more mature markets.

[1] In Indonesia, the DFS offering fits in two broad categories: ‘Laku Pandai’ basic savings accounts, only offered by the banks and ‘Layanan Keuangan Digital’ (LKD) e-money services, offered by both banks and non-bank.

[2] Agent dormancy estimates are based on the mapping exercise during data collection. While there is no publicly available data on customer dormancy in DFS, based on internal MicroSave analysis, it is estimated that customer dormancy in DFS ranges anywhere between 30%–55%

Agent Network Accelerator Research: Nigeria Country Report 2017

In 2014, MicroSave / the Helix Institute of Digital Finance, with the financial support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), launched the findings from the first wave of the Agent Network Accelerator Survey (ANA) Nigeria Country study. This report focused mainly on operational determinants of success in agent network management specifically agent network structure, agent viability, quality of provider support, provider compliance & risk.

This research is part of the Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) a four-year research project implemented in eleven focus countries, managed and conducted by the Helix Institute of Digital Finance. It is the largest research initiative in the world on mobile money agent networks, designed to determine their success and scale. Nigeria is among the eleven African and Asian countries participating in this research project.

The second wave of the ANA Nigeria study is focused on identifying strategic gaps and opportunities for scaling-up Digital Financial Services, with highlights on the implementation progress following the Helix Institute’s recommendations in the ANA Nigeria research conducted in 2014. Click the download button to read the full report.

Agent Network Accelerator Research: Indonesia Country Report 2017

The Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) is a four-year research project implemented in eleven focus countries, managed and conducted by MicroSave and the Helix Institute of Digital Finance. It is the largest research initiative in the world on mobile money agent networks, designed to determine their success and scale. Indonesia is among the eleven African and Asian countries participating in this research project, selected for its contribution to the development of digital financial services globally.

The second wave of the ANA survey in Indonesia builds on the findings of the qualitative assessments of Indonesian agent networks completed in 2014. The survey is based on a sample of 1300 DFS agent interviews that were conducted across 15 provinces in Indonesia during the months of July-September, 2017. The survey is designed to provide valuable insights on the digital financial services sector in Indonesia and provides recommendations for developing sustainable agent networks in the country. This report highlights the key findings of the research.

Business correspondent models in Bihar -Constraints and way forward

The study on Business Correspondent Models in Bihar- Constraints and Way Forward was commissioned by DFID’s PSIG Programme and SIDBI to improve the current body of knowledge around the status of the BC model in Bihar, to provide recommendations to improve the effectiveness of the model and to offer inputs to policymakers.

Key New Year Resolutions for the Success of Digital Financial Services

First of all, let me reaffirm my belief that digital financial services (DFS) really do have the potential to provide financial inclusion for many (but perhaps not all) of the 2 billion un-banked. Its potential to reduce the costs of providing a range of financial services is an exciting prospect for those of us who have long critiqued the monoculture of microcredit. And the potential of DFS is already being hinted at in recent studies – most recent, “The Long-run Poverty and Gender Impacts of Mobile Money” by Tavneet Suri and William Jack, is particularly encouraging:

“We estimate that access to the Kenyan mobile money system M-PESA increased per capita consumption levels and lifted 194,000 households, or 2% of Kenyan households, out of poverty. The impacts, which are more pronounced for female-headed households, appear to be driven by changes in financial behavior—in particular, increased financial resilience and saving—and labor market outcomes, such as occupational choice, especially for women, who moved out of agriculture and into business.” – Tavneet Suri and William Jack

However, DFS is currently facing two big challenges that have the potential to undermine all the progress made to date:

1. Digital Credit

Access to small amounts of credit with a few key strokes can be immensely important and valuable for people facing short-term cash-flow problems or emergencies. So digital credit meets important demand – as the enormous uptake of such products in East Africa have demonstrated. But it does carry important risks for consumers and the industry as a whole.

With a few honourable exceptions, notably Equitel’s Eazzy Plus loan (which draws on Equity Bank’s customer transaction data) and the KCB-M-PESA loan, most digital credit products currently on offer bear all the hallmarks of consumer or pay-day lending. Their annualised percentage interest rates contain high risk premiums. This is understandable in that, for all the hype, low-income people leave very shallow digital footprints because of their limited use of mobiles – for calls, messages, or sending money. But few digital credit providers reduce interest rates for those customers who do build up deep digital footprints through high levels of activity on the network and/or regular on-time payment their loans. Instead, they are rewarded with offers of higher loan amounts at the same, risk premium-inflated, interest rates.

For the leading players at least, these interest rates do compare (sometimes even favourably) with the 10% per month interest rates typically charged by the informal sector lenders in East Africa. But I am not sure that this is the right benchmark to which we should aspire.

CGAP and others have also been raising important questions around customer protection measures as well as the opaque terms and conditions surrounding digital credit. The Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) has taken important steps to ensure that: (1) borrowers are presented with key elements of the terms and conditions as part of the process of accessing their loan on their mobiles; and (2) lenders provide both negative and positive reports to the reference bureaus active in the country.

Nonetheless, the growing numbers of clients blacklisted for outstanding loans of >90 days on the credit bureaus is a matter for profound concern. After alarming newspaper articles on this, MicroSave called the leading credit bureau in Kenya and was told that the reports were correct. The bureau has about 10.6 million listings for digital credit borrowers, out of which about 2.7 million are negative. We do not have the full data set to corroborate these numbers, but there seems little reason to doubt them, given their source.

This would suggest that digital credit has already resulted in the effective financial exclusion of 2.7 million people in Kenya. And that, if this trend persists, providers of digital credit will soon run out of borrowers.

It is intriguing to speculate as to why so many people should fail to repay their typically small digital credit loans. Part of the problem may lie in borrowers’ lack of ability to pay, and part in lack of understanding (despite the efforts to clarify terms and conditions and use of SMS reminders to encourage people to repay on time) … but I would suggest that an important part lies in the ease of accessing these loans. And that some digital credit providers actually push these loans at potential borrowers.

I wonder if providers (or CAK) need to encourage user-defined friction to address these latter problems, in an attempt to avoid the ill-considered, non-essential loans that are taken out, particularly in bars on Friday and Saturday evenings. Users could, as part of the initial registration process, define additional criteria such as the credit being only available after a day’s cooling off period (during which the application could be cancelled). To provide for emergencies, when the one-day cooling off period could present a real problem, a user-defined, second PIN could be added to override this provision. To be effective, this type of product engineering must be developed through careful research into consumers’ needs, perceptions, aspirations and behaviour – as outlined in The Helix’s training on Product Innovation and Development.

We need to understand the consumer experience and what behavioural levers might be used to nudge them towards better self-protection much better than we currently do. In addition, as AFI and CGAP have already flagged, additional regulation and oversight is needed, given the burgeoning of digital credit and the challenges it presents to regulators. It was, therefore, excellent to see the ITU working group on Consumer Protection in DFS make such a robust set of recommendations.

2. The Trust Deficit

DFS depend on customers’ trust in the systems and agents used to deliver the service even more than in traditional financial services. Protecting the customer and minimising the risks as he/she uses the service is essential to build and maintain that trust. And yet, in most of the 20 markets where MicroSave has worked on DFS, a combination of service/system downtime, agent illiquidity and churn, complex USSD/SMS-based user interfaces, and poor customer recourse means that there is limited trust in DFS. As a result, many users prefer to perform over-the-counter (OTC) transactions rather than take the risk of keeping money in their wallets or sending it to the wrong recipient. We often hear that financial education or marketing will overcome these barriers – but I suspect that this belief is over-optimistic.

Many of these issues require providers to invest more in their platforms and agent networks in order to build a comprehensive and thus profitable digital ecosystem, beyond an OTC-based and payments-dominated one. This is a “hygiene factor” pre-requisite for transforming DFS into real financial inclusion and rolling out a range of services.

Smart phones may provide the key to realising the full potential of DFS ecosystems. Smart phones allow us to build interfaces that are much more intuitive for the end-user, and to reflect the mental models that poor people use to manage their money.

Zooming out to see the big picture

Ultimately we need an over-arching strategy to address the two inter-related challenges of trust and digital credit. We need to encourage low-income people to maintain and use digital liquidity, thus deepening their digital footprints and allowing digital credit providers to reduce their interest rates. G2P and other bulk payments will be key to creating digital liquidity – some important work is underway on this already. Digitising a wide variety of value chains and procurement/distribution platforms as well as retail merchant acceptance ecosystems will also be essential to keeping money digital and circulating it.

But the success of these efforts will depend on addressing the hygiene factors that currently undermine trust in digital financial services. Only this will lead to a trusted, convenient and efficient digital ecosystem, with increased volumes, reduced costs, increased providers’ profitability and, ultimately, deeper digital footprints to inform digital lending operations.