Bangladesh reduces poverty and vulnerability through its Social Safety Net (SSN) programs using cash assistance. These programs support the elderly, widows, persons with disabilities, women, and men of working age with temporary employment. The programs also support young mothers and children. Before digitizing the SSN payments, most beneficiaries had to wait long queues and travel long distances to receive the payments. During COVID-19, many were worried about how they would receive their payments. Then, in the fiscal year 2020-2021, the Bangladesh government introduced a digital intervention through MFS, which supported 25 million beneficiaries. This initiative also ensured that the beneficiaries had financial freedom and easy access in rural areas of Bangladesh.

Blog

How has the pandemic changed the way LMI people in Vietnam save?

The digital savings and payments channels carry the immense potential to increase access to basic banking services. The changes in the payments landscape due to the pandemic have altered people’s outlook in Vietnam. Digital payments solutions, such as mobile, QR, and card payments, saw an upward trend in Vietnam as people preferred the convenience of saving and paying digitally.

The “Innovate, Implement, Impact” or “i3” program, supported by the MetLife Foundation, uses digital technology to provide better opportunities for people to plan, save, borrow, and spend safely. Further, the video explores the digital journey of Vietnam during the pandemic.

Is access to smartphones essential to bridge the digital divide?

Usage of smartphones appears to increase household income and consumption. Both quality (relatively) cheap smartphones and 3G+ coverage are increasingly available throughout Africa. But the majority of households have very limited disposable income both to buy a smartphone, but in particular to purchase data. The prohibitive cost of data stops many using the internet/apps and those that do “sip” rather than “surf”. The result is a significant and persistent usage gap, even as the coverage gap reduces. Orality and lack of digital capability mean that icon- and IVR-driven interfaces will be essential to build self-initiated usage. But much of the shift to internet/app usage must be assisted and mentored by agents. Agents offer a range of real advantages but also a wide variety of risks/consumer protection concerns which will require attention.

The resilience of bank agents in Bangladesh through the COVID-19 pandemic

Bangladesh sanctioned and launched agent banking in 2013 to provide alternative and accessible banking services to its underserved and underprivileged population. As of 2021, 13,591 banking agents opened 11 million bank accounts through 18,314 banking outlets. However, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, Bangladesh imposed lockdowns and stay-at-home orders that prevented businesses, including banking agents, from generating income. Despite the hard barriers, like many other agents, 60% of Bank Asia agents did not stop operating even when the commercial branches were closed. They borrowed money from friends and family members to continue their banking operation and supported the government by disbursing assistance funds to vulnerable people.

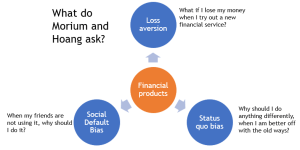

Different yet similar—the behavioral biases of low- and moderate-income segments in Bangladesh and Vietnam

The biases of the LMI segment and product development lessons for providers

Our previous blog showed that Bangladesh and Vietnam have some macroeconomic similarities yet differences. This blog examines the similarities, and even differences, in biases through the lives of two low-and moderate-income LMI segment protagonists, Morium from Bangladesh and Hoang from Vietnam.

Our work suggests three distinct behavioral biases drive people’s decision-making from the LMI segments while using digital financial services (DFS)—loss aversion, status quo bias, and social default bias. There are several other biases, but financial service providers (FSP) seeking to serve LMI people with DFS will always face these three key ones.

What do they face?

Morium works in a readymade garment (RMG) factory on the outskirts of Dhaka. During the pandemic, she received her salary in her mobile financial services (MFS) wallet but still primarily uses cash for day-to-day transactions. Hoang hails from the north-central coastal district of Quỳnh Lưu in Vietnam. She has been running a grocery store for the past five years and is relatively tech-savvy.

How should FSPs factor in these biases when designing products for the LMI segment? Understanding and responding to these biases is key to effective product design.

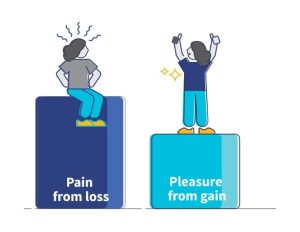

Loss aversion

Loss aversion is best encapsulated by “losses loom larger than gains.” Morium lives on a salary that is just about sufficient to make her ends meet. Hence, she wants to make low-risk choices and avoid losses from incorrect financial decisions. She wishes to save money cautiously for the future. She, therefore, invests in the Deposit Pension Scheme (DPS), a formal recurring deposit instrument used by millions of LMI people. On the other hand, Hoang does not trust banks and chooses savings options that she believes carry a lower risk. She prefers to keep cash at home and with informal associations and clubs comprising people she knows and trusts.

When she sends money home through mobile money, Morium depends on agent-assisted transactions, as she fears sending money to the wrong account.

Status quo bias

Status quo bias is seen in people who persist with their current practices and resist any new behavior. People tend to continue with the old system unless they find a strong enough reason to change.

After COVID-19 hit, the Government of Bangladesh mandated all RMG factories to transfer salaries to workers’ MFS wallets. Morium received her salary in her bKash wallet for the first time. Prior to this, she has always used cash to buy her daily needs from grocers and merchants. Due to this status quo behavior, even now, she withdraws her salary (at an MFS agent point) and spends in cash rather than using her MFS wallet to pay digitally for her purchases. Morium exhibits status quo bias because had she not withdrawn money in cash, she would have saved on the 1.85% cash-out fee she has to pay the agent – about BDT 185 (USD 2.15) for her BDT 10,000 (USD 116) salary. bKash P2P charges are BDT 5 (USD 0.058) for transactions of less than BDT 25,000 (USD 290) (for that month), so she would have to do 37 of these before cashing out became a rational economic decision. Status quo behavior can be expensive!

Hoang wants to borrow formally but hesitates to visit banks due to the hassles of providing collaterals and navigating complex documentation requirements. She is more comfortable maintaining the status quo by borrowing from informal sources. Even though she knows of the risks, she shuns buying insurance cover. She perceives it as an expensive product for the rich. She maintains status quo bias by depending on informal support groups. The idea of saving now and reaping benefits later does not appeal to them.

Social default bias

Individuals exhibit this bias when they can or do not make informed decisions and copy others’ choices. Morium tends to follow the “leaders” in her factory who influence major financial decisions. Despite owning a mobile phone and an MFS wallet, Morium follows her friends and exhibits social default bias by making P2P transfers with the help of an agent. Stories of DFS-related fraud, instances of siphoning value out from wallets, sending money to the wrong customers, and cautionary media news weighs heavily on her mind and pushes her to display this bias. Even when it comes to savings, Morium saves in DPS, just like her friends.

Address bias through smart product design

FSPs can create a strategy that takes these biases into account by scrutinizing the requirement of customers using the eight Ps of the marketing framework—product, price, place, promotion, people, process, physical evidence, and positioning. Doing so will help them overcome the barriers that often prevent LMI people from accessing DFS.

Product:

- Morium and Hoang are attached to their current ways of managing their finances. People will buy your product only if it offers an easier experience than their current one. Break status quo bias with product features such as zero savings balance, high liquidity and easy access, quicker turnaround times, and no penalties.

- Stop trying to attract customers with high return rates alone. A combination of liquidity, safety and return (in that order of priority) may address loss aversion better.

- Mimicking the features of informal financial systems familiar to LMI users helps overcome status quo bias. For example, MSC supported the FinTech Kosh to mimic microfinance digitally.

- Use the power data to offer need-based products. MSC supported the FinTechs Finarkein and Numer8 to optimize the power of data for product design.

Price:

- Hoang worries about the high price of products. Keeping costs low and affordable for LMI people, who often run on a tight budget, can help address loss aversion and social default bias. Many FinTechs offer affordable savings using this principle.

- Help them to start small and build habits. Fintech Lakshya helps people save as low as INR 5 (USD 0.07) and build a habit.

- Build sachet products (like insurance). MSC helped one provider in Vietnam to roll out a small premium product to insure against COVID-19.

- Allow flexible loan repayment installments (amount and frequency), flexible savings installments, flexible premiums to care of the triple whammy faced by LMI segments—uncertain income, small amounts, and irregular income.

- Ensure that pricing is clear and transparent—build trust to undermine status quo bias and, eventually, enable social default bias in favor of your product.

Place:

- Morium fears stepping into banks to access financial products. Offer her products in surroundings familiar and comfortable to her. FSPs can partner with aggregators, mom and pop stores, agent outlets, post office outlets, and community centers. MSC is working with several FSPs in Bangladesh to offer financial products through some of these outlets.

- If you build digital marketplaces or platforms, make sure they are in a local language, with colloquial terms, are easy to navigate, and have less clutter. And remember that many people are oral, so intuitive interfaces are key.

Promotion:

- Build marketing strategies that appeal to the needs of LMI people using local language and cultural context. MSC has helped many FinTechs build this in India—Bridge2Capital, myPaisa, Navana tech.

- Communicate the benefits of products straightforwardly using words that people from the LMI segments use. Train your staff and cut the jargon!

- Many LMIs use WhatsApp and YouTube for entertainment, use these wherever possible for promotion, education, and marketing.

People:

- Ensure that human customer touchpoints are easy to reach, knowledgeable about the product, and sensitive to the needs of LMI customers. This comfort breaks the status quo behavior of the likes of Morium. Learn from Bangladesh’s microfinance!

- Enable and support agents to build trust. Remember that the bank security guard is probably the preferred touchpoint for LMI people coming to your bank branches.

- Partner with influencers and local entities. This helps use social default bias to your advantage. Frontiers Markets in India uses SHG leaders for social commerce.

Process:

- Shorten forms, reduce paperwork, and limit data fields. This allows people to sign-up quickly and try something new by reducing status quo bias.

- Think of ways to mimic the features of informal financial systems familiar to LMI users. These have great simplicity. Hoang is comfortable with informal clubs; can your financial product give her the same comfort and ease?

- Use a combination of technology and in-person support to break status quo bias. BRAC Bank in Bangladesh banks on technology and agents through its bKash network to reach the last mile.

- LMI people employ coping mechanisms, such as animating money, income shaping, and liquidity farming extensively in their lives. Keep this in mind, and use these design principles.

Physical evidence:

- The status quo springs from a fear of the unknown. Create a physical environment that is welcoming, familiar, and helpful with clear and concise signage in the customers’ language. When MSC first worked with Equity Bank, we saw farmers leaving their shoes at the door of the bank’s polished marble branches.

Positioning:

- FSPs should build customer protection in their solutions. Toll-free phone numbers that work, empathetic agents, responsive and supportive grievance redress systems will build customer trust.

- If you feel that building a brand will take time, partner with a known brand to which LMI people can relate to address the status quo and social default bias. Customers value the safety and security of products—so use this to address loss aversion bias. Fintechs that offer savings and investment products partner with well-known banks and mutual fund houses.

- Focus on emotional appeals that resonate with LMI customers. Our i3 program partner in Bangladesh, Apon Wellbeing, stresses “workers wellbeing” in its pitch. It stresses the importance of health, hygiene, and nutrition in its product offering, which helps people shun the status quo bias.

Conclusion

Biases are not specific to LMI segments. These are inherent human behaviors and are challenging to overcome. But what FSPs can definitely do is create products that appeal to this population and nudge these users into using these products. Thinking about the 8 Ps should at least help them offer an antidote to some biases. However, it will be a trial and error path with no successes guaranteed.

How have nano and micro-entrepreneurs transformed during and after the most extensive lockdown in Vietnam?

Microenterprises in Vietnam account for more than 98% of the business, 40% of the GDP, and 50% of the total employment. The COVID-19-induced lockdown restrictions prompted many merchants to go digital by selling foods and drinks online through super apps. The “Innovate, Implement, Impact” or i3 Program, supported by the MetLife Foundation, creates opportunities for nano and microenterprises to go digital and “cashless.”

Watch our video for more updates on the i3 program in Vietnam.