GreyMatter is a startup under the Financial Inclusion (FI) Lab accelerator program’s fifth cohort. The Lab is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations worldwide—the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network. MSC is a partner to the FI Lab, part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative.

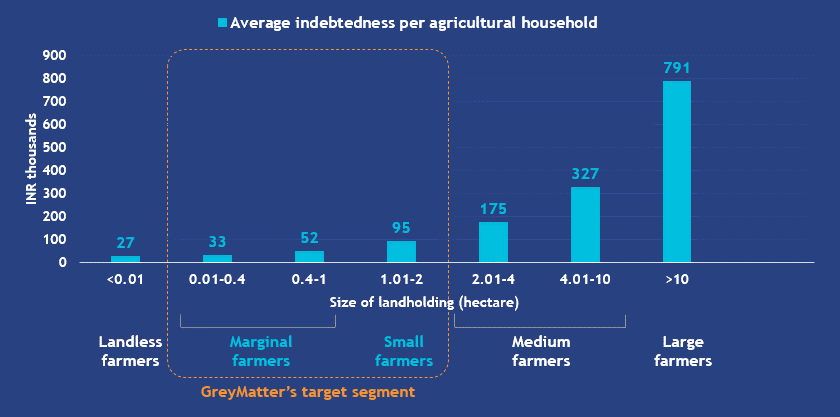

As per the National Statistical Office’s (NSO) latest report, 31%[1] (93.09 million) of Indian households depend on agriculture as their primary source of income. Around 82% of these households are small or marginal, of which almost 70% of households spend more than they earn to meet their basic needs. This pushes them into a vicious cycle of debt—even for basic needs, let alone an emergency. The NSO report further warns that more than 50% of agricultural households are indebted, and the numbers continue to rise. Alarmingly, farm debt has increased by 58% in the last five years. The average outstanding loan per household stands at INR 74,121 (~USD 988) in 2018, compared to INR 47,000 (~USD 627) in 2013.

Figure 1: Average indebtedness per agricultural household in India

NSO’s report states that medium and large farmers took 69.6% of outstanding agriculture loans from institutional sources like banks, cooperative societies, and government agencies. A limited number of small and marginal farmers (SMFs) availed of such loans. The remaining SMFs borrowed money from informal sources like local moneylenders or friends and family. Respondents cited several reasons for availing of loans from informal sources—the farmer-applicants were unqualified to borrow from formal institutions, the processes were too lengthy, and interest rates against MFI-based loans were too high.

What does GreyMatter wish to solve?

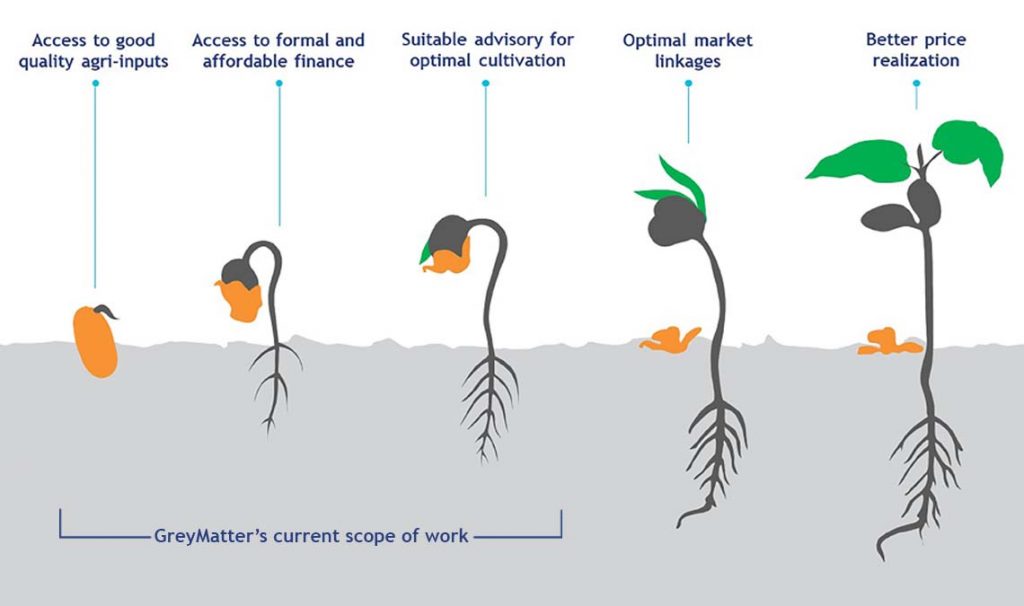

Every day, SMFs in India battle multiple challenges—access to finance is just one among many issues. GreyMatter currently provides them access to finance and quality agri inputs, and is working towards helping them with other phases of the value chain.

GreyMatter’s current work focuses mainly on solving issues farmers grapple with during the initial phase of every crop season, as shown in the figure below.

Figure 2: Areas that smallholder farmers need assistance with

Upaz—from an idea on paper to its implementation as a unique product

These challenges compelled IIM Indore alumnus and Chartered Financial Analyst Neetesh to take matters into his own hands. He had been in the industry for more than 11 years and was associated with the OneAcre Fund before starting GreyMatter.

These challenges compelled IIM Indore alumnus and Chartered Financial Analyst Neetesh to take matters into his own hands. He had been in the industry for more than 11 years and was associated with the OneAcre Fund before starting GreyMatter.

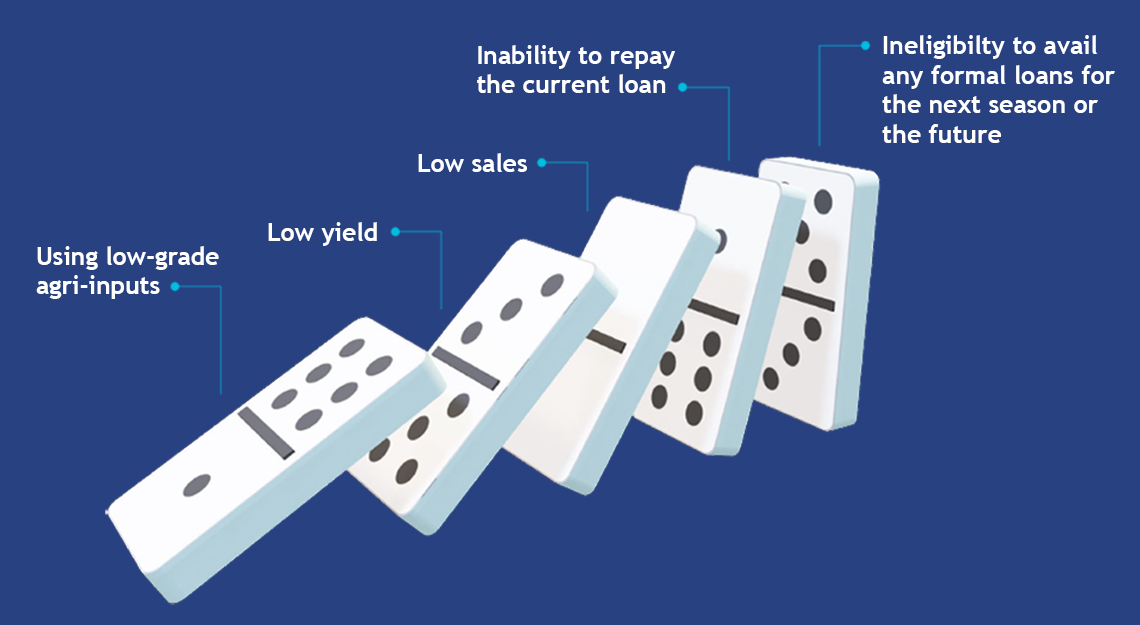

The industry largely believes smallholder farmers struggle the most with inadequate access to affordable formal finance, which hinders their growth. However, this statement is only partially true. Even if farmers get their hands on formal credit, they often fall prey to local agri-input traders who trick them into buying low-grade agri-inputs for a higher profit margin. If the farmers protest, the traders refuse to supply agri-inputs. Here, the farmers have almost no bargaining power and accept whichever agri-inputs the trader sells them.

Moreover, farmers lack suitable guidance and struggle to grow healthy crops. Unhealthy crops lead to a lower-than-estimated yield, further lowering their income from selling the produce. Since the farmers earn less, they find it difficult to pay their loan installments in full, which pulls them into a—largely informal—debt trap. This is a textbook example of the “domino effect,” as represented in figure 3.

Figure 3: The “domino effect” in smallholder farming, which leads to accumulated debt

This segment specifically needs effective interventions throughout the entire value chain. As shown in figure 2, these farmers need help with access to formal finance and access to quality agri-inputs alike, up until they sell their produce. A bid to solve this problem spurred Neetesh to create Upaz. The product is based on the buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) model, enabling smallholder farmers to access quality agriculture inputs at the best possible prices through affordable financing.

It was important for GreyMatter to ensure that the farmers use the funds only to generate income through farming and do not divert them for personal consumption. The NSO report notes another disturbing feature that only 57.5% of the total loans that respondents availed during the survey were explicitly used for agricultural purposes. This moved GreyMatter to provide in-kind credit to farmers in the form of agri-inputs instead of cash. The total loan amount is divided into six-month EMIs, which the farmers repay during the same crop season. The startup’s offering makes it convenient and affordable for farmers to purchase good-quality agri-inputs using a formal loan process that creates a credit score for them in the background.

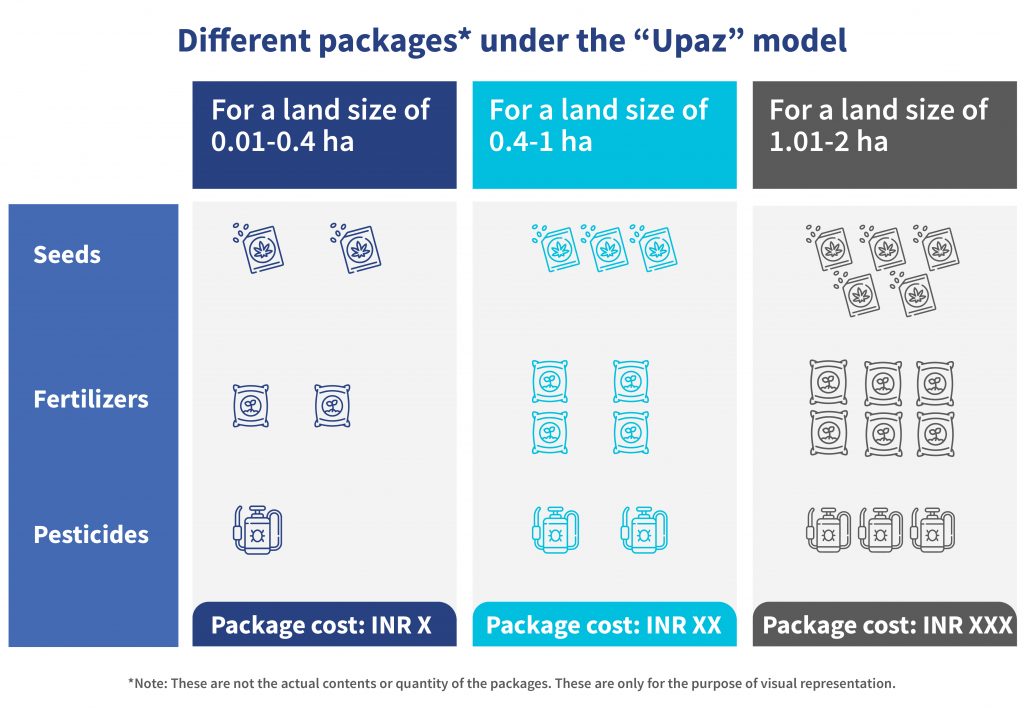

GreyMatter employs an engine that recommends the right amount of agri-inputs for its users based on their land size and the crop type. Under the Upaz model, farmers can choose from an array of land size-based packages that apply to them, curated specially for a particular land size, which considers the region, soil types, and other factors that would determine different types or quantities of agri-inputs. Moreover, these packages are customized to fit both the crop seasons—Kharif and Rabi.

Figure 4: Example of different packages offered to smallholder farmers under Upaz

First, the farmers select a suitable package. Then a field officer places a collective order for agri-inputs on behalf of all the farmers in a particular panchayat or village. Within a few days, the company delivers the order at a pre-decided location in the village, which all the farmers can access. GreyMatter’s field officers then distribute the agri inputs equitably among farmers based on their orders.

Currently, GreyMatter procures its agri-inputs from national and state-level distributors. As it adds a substantially higher number of farmers to its network, it plans to procure products directly from manufacturers, as it could then place higher volumes of orders. This will lead to a further reduction in the unit prices of different agri-inputs.

What sets GreyMatter apart from other agri-commerce players out there?

Figure 5: Factors that differentiate GreyMatter from other service providers in the agricultural sector

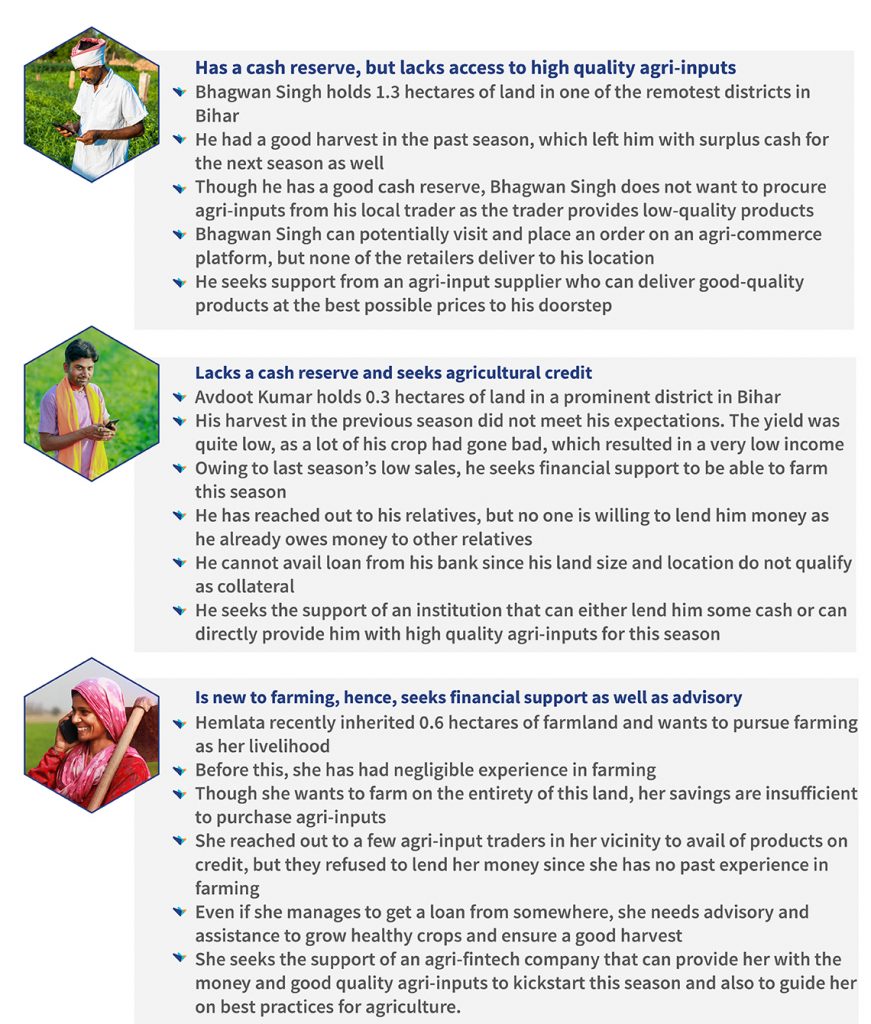

Upaz can cater to different types of farmers who may have varying needs

Figure 6: Three use-cases where GreyMatter can add value to farmers

Support from the FI Lab

The Lab has offered a holistic support package to GreyMatter, ranging from mentor hours and grant capital to field studies led by financial inclusion experts in consumer and market insights. The support helped GreyMatter understand its users and their scope of usage better to build a more resilient, robust, and impactful solution.

The impact made till now and its vision for the future

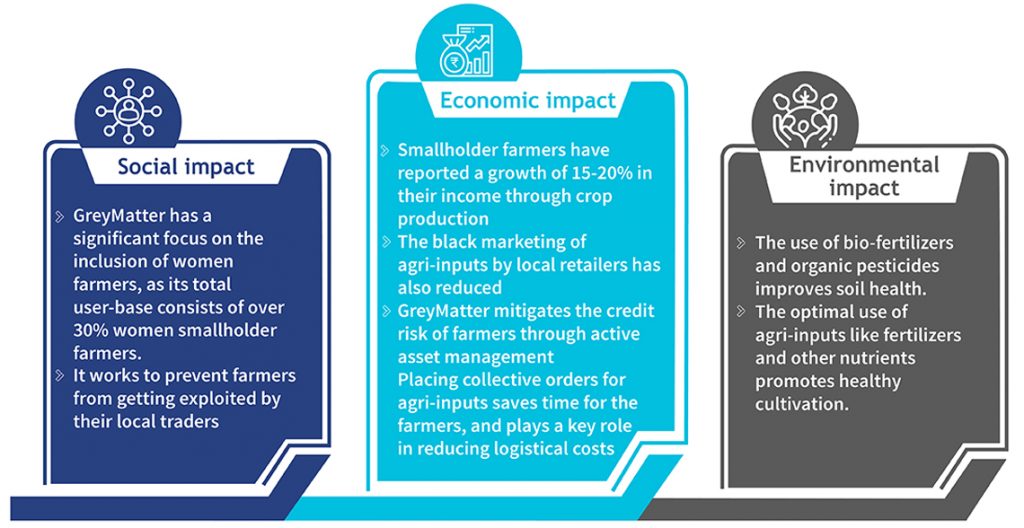

GreyMatter has been operational since October, 2021. Currently, the service is live in the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, with a direct impact on the livelihoods of more than 2,500 active users in its service network. However, the impact can be categorized further into the following:

Figure 7: Classification of the impact made by GreyMatter

Currently, GreyMatter is on track to expand to more than 240 villages in India, engaging a total user base of 10,000-plus smallholder farmers. While the startup is currently powered by only one financing partner, it will onboard a few more banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) as financial partners. By 2024, GreyMatter intends to extend its services to 700,000-plus farmers like Bhagwan Singh, Avdoot Kumar, and Hemlata in India.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs making a difference for underserved communities. These startups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll #BuildingForBharat

[1] Population of India, as of 2020 – 1.38 billion; Average size of a rural Indian household, as of 2012 – 4.6 persons

Fresh graduates in India lack employability skills in the tertiary sector, while agricultural employment continues to plummet. As a result, many continue to join India’s sizeable blue- and grey-collar workforce.

Fresh graduates in India lack employability skills in the tertiary sector, while agricultural employment continues to plummet. As a result, many continue to join India’s sizeable blue- and grey-collar workforce.

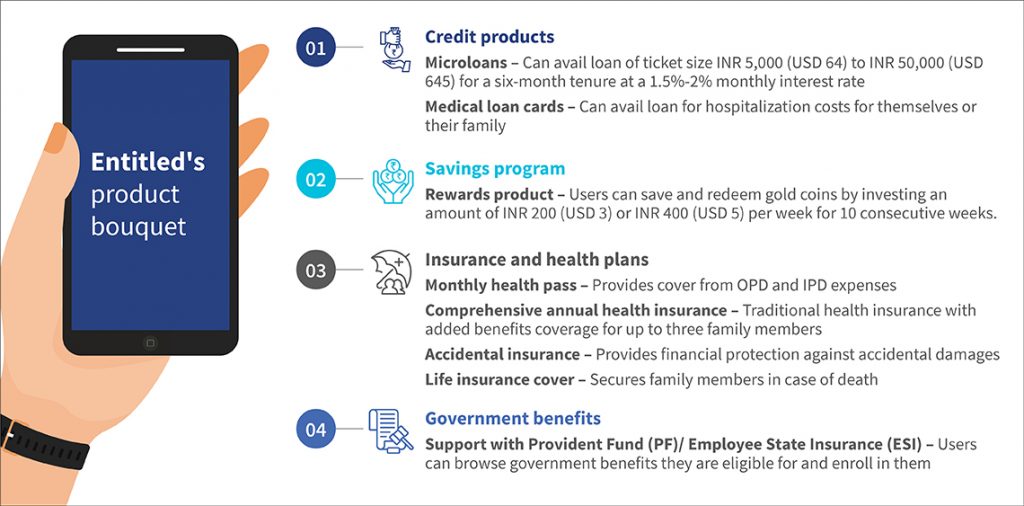

Entitled acknowledges it is essential to reach workers through their employers and an interface they can trust. At present, Entitled communicates with its beneficiaries using a WhatsApp chatbot.

Entitled acknowledges it is essential to reach workers through their employers and an interface they can trust. At present, Entitled communicates with its beneficiaries using a WhatsApp chatbot.

FLYK was Apratim’s second startup. He had met Prafful while developing his first app. Prafful was drawn to startups that worked to make a social difference. Apratim and Prafful decided to build the platform together to enable meaningful change for rural customers through loan services.

FLYK was Apratim’s second startup. He had met Prafful while developing his first app. Prafful was drawn to startups that worked to make a social difference. Apratim and Prafful decided to build the platform together to enable meaningful change for rural customers through loan services.

With 8,000+ successful downloads, FLYK is taking its first steps toward success. The startup has processed about 1,508 loans until April 2022 and envisions expanding rapidly. Out of 635 users, FLYK has an 86% retention rate on its platform.

With 8,000+ successful downloads, FLYK is taking its first steps toward success. The startup has processed about 1,508 loans until April 2022 and envisions expanding rapidly. Out of 635 users, FLYK has an 86% retention rate on its platform.

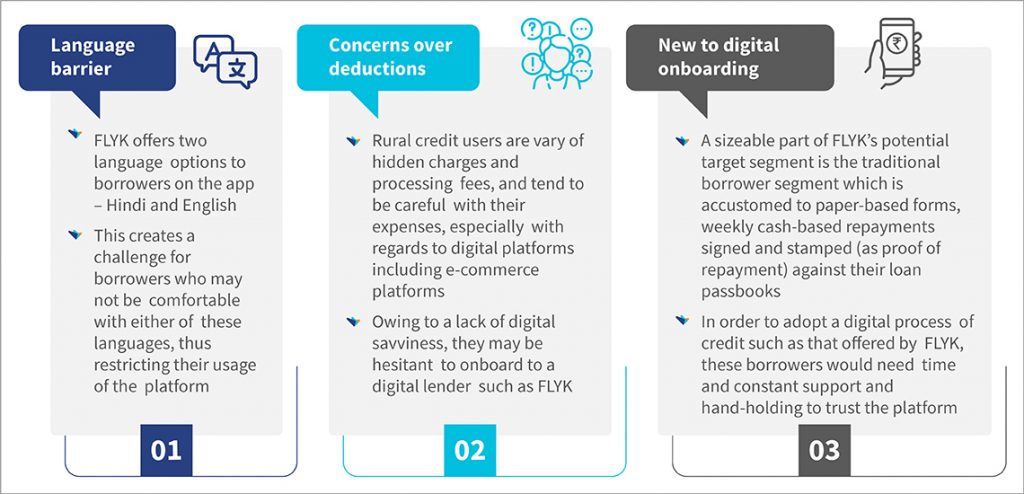

Customer challenges to adopting FLYK

Customer challenges to adopting FLYK