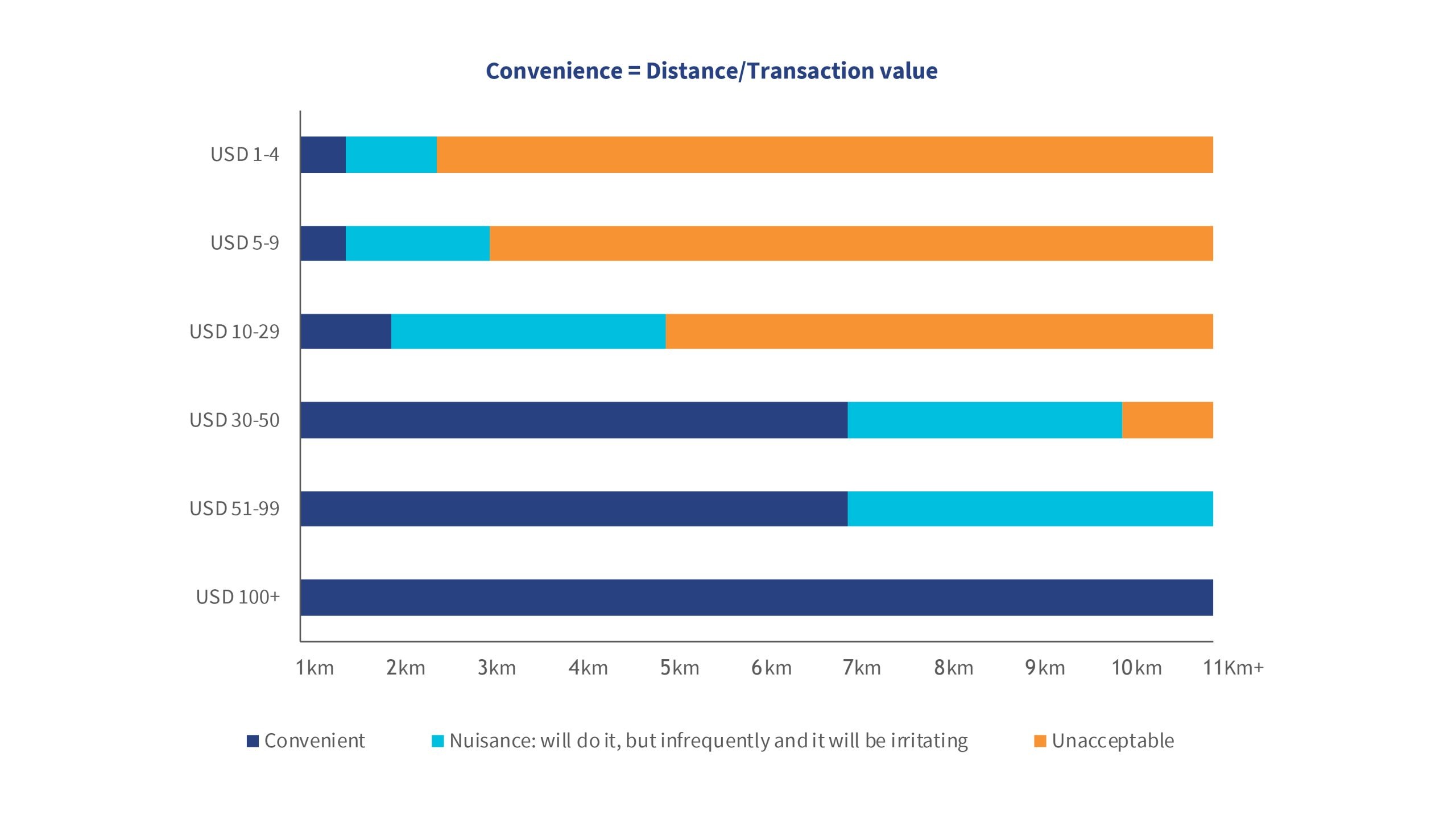

The digital financial services (DFS) landscape of Bangladesh evolved multifold in 2019. This can be traced to the efforts of the government, the banking regulator, and policymakers in Bangladesh. As of December 2019, the country had 971,000 MFS agents who, on average, conducted 7.33 million daily transactions worth USD 156 million. Bangladesh has a total of11,320 agent banking outlets that serve 5.26 million customers. At present, 16 companies offer mobile financial services and 21 banks offer agent banking services. In addition, nearly 92% of the population now live within 5km of a financial sector access point.

TIGHTENED MONITORING: In 2019, two providers had to close their mobile financial services (MFS) operations-IFIC and Exim Bank. The providers did not have a substantial market share and were on the verge of being instructed to surrender their MFS licenses by the regulator due to their long-term dormancy in the market as MFS players. This move propagated a clear message-the regulator has tightened its grip on MFS and every player is expected to perform.

THE LAUNCH OF EKYC: Bangladesh Bank (BB), with approval from the Election Commission, initiated a pilot on e-KYC in September, 2019 with 15 commercial banks and two MFS providers. The list of participating commercial banks included state-owned commercial banks and agent banking providers, while bKash and Rocket were the two MFS players. The ICT Division of the government launched a gateway for easier and faster verification of national identity cards (NIDs). The “Porichoy” portal, which is connected to the Election Commission (EC) database, enables public and private organizations to provide services by verifying the NID cards of their customers. Electronic Know Your Customer or e-KYC mechanism, is a convenient process for the customers and helps reduce cost and time during enrollments.

INCREASED MFS TRANSACTION LIMITS: Bangladesh Bank raised the transaction ceiling for MFS in May, 2019. This had been a consistent demand from various industry players and policymakers. The increased limits affected multiple payment services that the MFS providers offered, such as inward remittances, e-commerce payments, business payments for micro and small enterprises, and payroll disbursements across the country.

PSP LICENCE AND E-MONEY GUIDELINES: BB issued guidelines for e-money service (EMS) in February, 2019 to highlight the transaction limits for e-wallets and to identify who can issue e-money. In July, the central bank increased the limit of transactions for e-wallets and clarified that only providers with a payment service provider (PSP) license can offer e-wallet services. At present, Bangladesh Bank has licensed iPay and Dmoney as payment service providers. This was a proactive move from the regulator to clearly state that FinTechs can operate in Bangladesh with a PSP license. Further, with the increased transaction limits, it sought to gain the acceptance of customers to FinTech services.

A major reason behind the success of various initiatives by the Bangladesh Bank is its support for the notion that innovations around use-cases are needed to drive transaction volumes and values. Guidelines such as widening the transaction limits and allowing non-bank entities to offer ATM services are critical to foster innovation and boost competition in the industry.

The future outlook for 2020

One aspect that we wished to include in our developments is the commitment of the regulator to drive the agenda for the financial inclusion of women. Bangladesh Bank has supported taking women agents on board and has made toolkits available for the industry players to develop financial products for women. The toolkit was a result of MSC’s study commissioned by IFC. BB also incentivizes banks to support the provision of credit to women entrepreneurs. Further, DFS providers target women workers in readymade garment factories with tailor-made products such as different cash-in and cash-out charges. Though these innovations drive gender inclusion in a way, we are yet to see these extended to the larger women population. MSC believes bridging the gender divide will be a top priority for Bangladesh Bank in 2020.

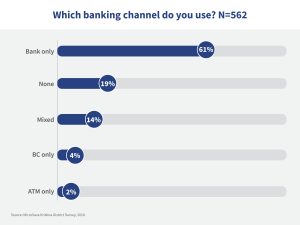

We also believe that the regulator will need to encourage agent banking service providers. Agent banking in Bangladesh has had organic growth until now. The country had 5.26 million agent banking customers, as of December 2019. The agent banking setup is complex and these agents have to invest around BDT 150,000-200,000 (~USD 2000) to start an agent banking outlet. However, we believe the providers may have been conservative in their outreach strategy. In countries such as India and Kenya, banks have been able to penetrate even the most distant areas through agents.

Another area, or rather, organisation that will demand the focus of Bangladesh Bank in 2020 is Nagad, the digital financial service of Bangladesh Post Office (BPO).The MFS service has already picked a significant market share by registering more than 10 million wallets and 130,000 agents across the country within the first nine months of its commercial operation. BB may want to work with BPO to ensure that the MFS players and Nagad remain competitive within a level playing field of market operations.

Finally, the initiative of Bangladesh Bank that allows non-bank entities to set up “White Label ATMs (WLAs)”and point-of-sale (POS) terminals is worth mentioning. As per the World Bank data from 2017, with 8.07 ATMs per 100,000 people, Bangladesh ranked the lowest in terms of the density of ATMs against the size of the adult population. This is in contrast to China, India, and Pakistan with 81.45, 22.07, and 10.44 ATMs per 100,000 people, respectively. These entities will operate under the payment system operator (PSO) license, as of September, 2019. At present, only three PSOs are operational in Bangladesh, as per a report from Bangladesh Bank. We believe this move will encourage the participation of the private sector in the financial services market.

Given that around 50 percent of its population remain unbanked, Bangladesh will need to take policy decisions to push the service providers further in 2020. MSC believes that the key focus areas for Bangladesh Bank shall be to push for technological disruption, expand its work in e-KYC, tailor the design of products and services for women, and utilize the potential of agent banking.

The blog was also published on The Financial Express on 13th of March, 2020

Only about

Only about