Meet Neha and Sarita, rural women based in Alwar, Rajasthan. Neha is a confident business correspondent (BC) agent who uses her smartphone effortlessly for many things, such as e-commerce. In contrast, her neighbor Sarita uses a shared household smartphone her husband owns, which she hesitates to use for e-commerce. Then, one day, Sarita’s fate changed when she tapped into her community and reached Neha, who inspired her to master e-commerce platforms.

This blog charts a journey from uncertainty to confidence through a community of practice (CoP) in the era of the digital divide.

(Learn more about MSC’s work on CoP). In this internet age, e-commerce enables entrepreneurs to access larger markets and diversify their income streams. It also helps users, especially women, reduce their dependency on traditional and often less accessible market channels. Thus, it increases their economic independence.

Community of practices: A step closer to bridge the gender divide

As per the Findex data 2021, about 80 million customers aged above 18 years made their first digital merchant payment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Almost 95% of all Indian districts have access to e-commerce platforms. Yet, disparities persist between the urban and rural areas. As per GSMA’s “The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity 2023” report, 10% of Indian smartphone users do not use the Internet, while 37% of the rural population is unaware of the Internet, and 15% do not know how to use it on a mobile phone.

Gender inequalities continue to plague the digital world. Women lack regular access to technology and digital products. As per GSMA’s “Mobile Gender Gap Report 2023,” women are 40% less likely to own a smartphone and use mobile Internet than men. Women’s usage of smartphones and the Internet in India for digital payments is 17% less than that of men, as per the Global Findex Database 2021. Their digital proficiency with smartphones and the Internet is limited to calling, short message service (SMS), and social media, such as WhatsApp and YouTube.

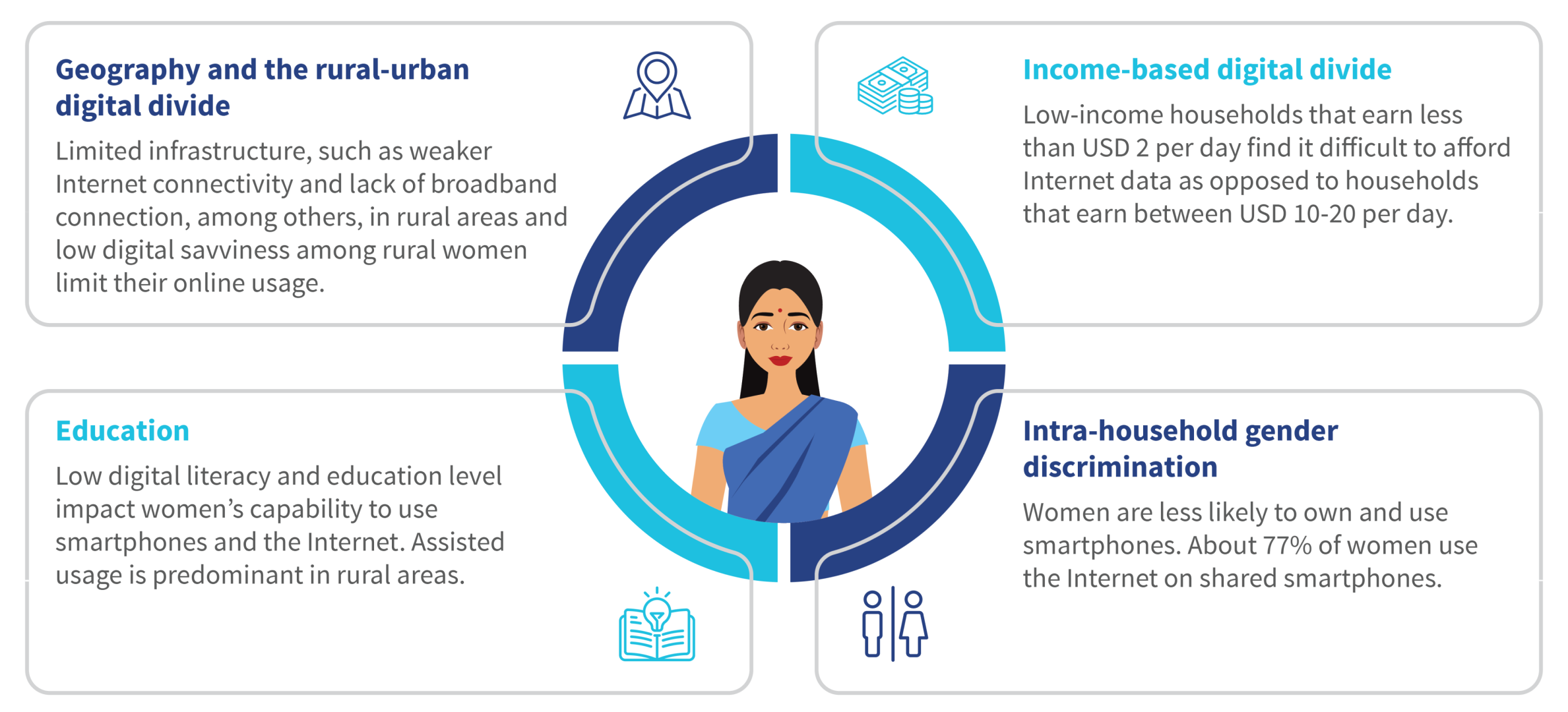

Primarily, four factors contribute to the digital gender divide:

We can significantly enhance women’s proficiency in e-commerce if we actively build their capacities. While this is easier said than done, MSC’s ground-level work with Frontier Markets provides a ray of hope as it builds and sustains a localized community of practice (CoP).

Driving women’s participation through CoP: Offline and online channels

A CoP is a “collaborative network where individuals bond over a shared interest or field and engage in collective learning and expertise development.” A CoP can play a key role to drive initiatives on the ground through peer-to-peer (P2P) learning and encourage more women to use e-commerce on the demand side as customers and the supply side as entrepreneurs. For instance, a field visit with Frontier Markets in Rajasthan revealed that women were eager to develop their capacities, diversify their income, and strengthen their financial resilience through e-commerce.

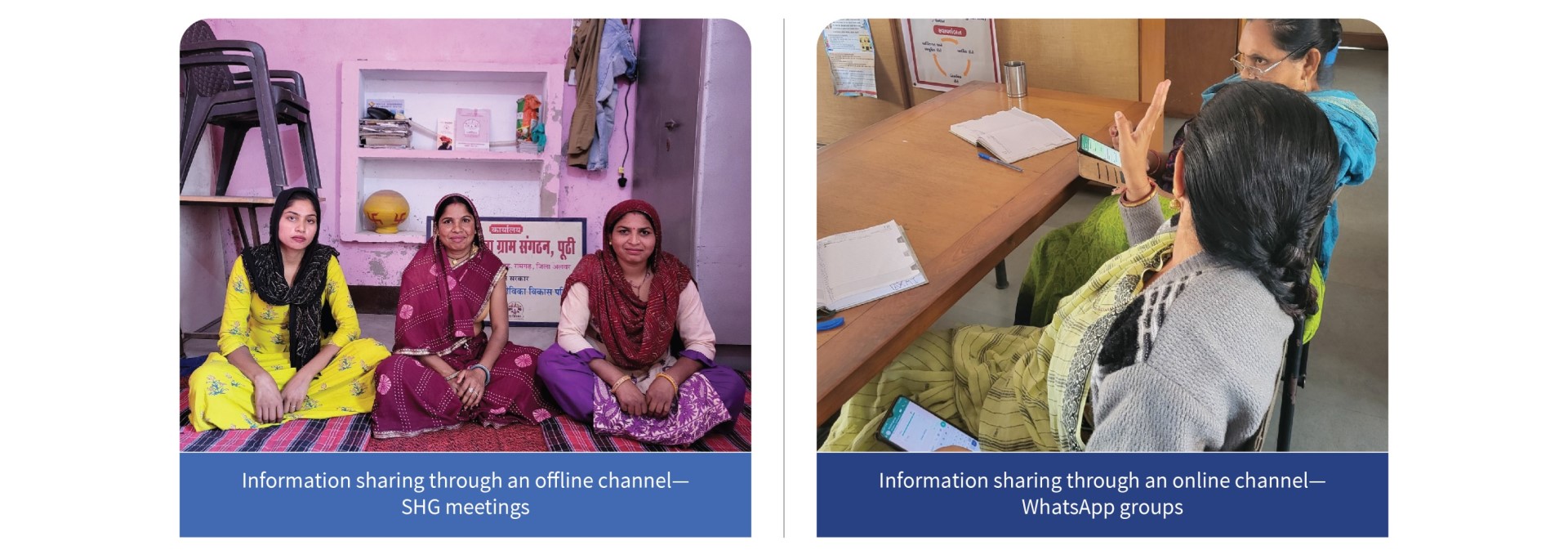

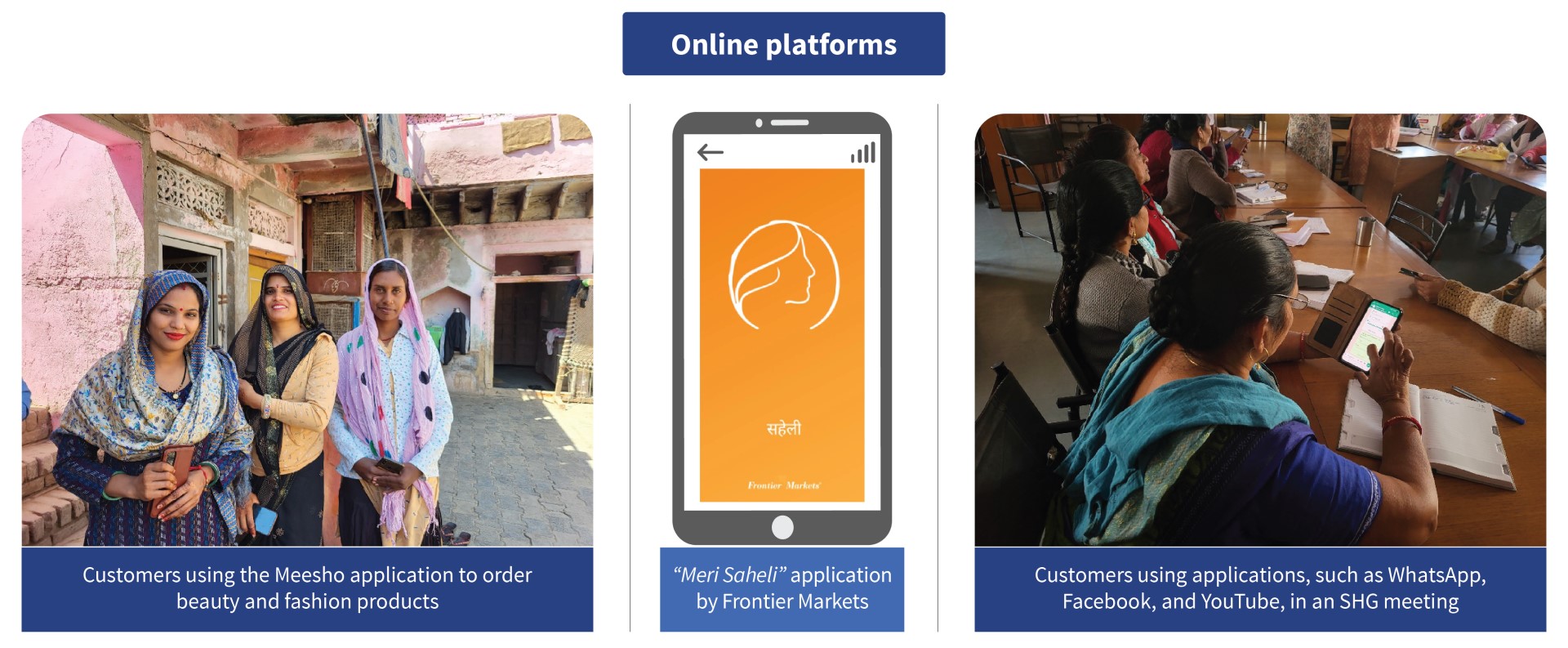

Stakeholders can build CoP initiatives through both offline and online channels. Offline channels include SHGs, while online channels include platforms, such as WhatsApp, Facebook (Meta), YouTube, Meesho, and Frontier Markets’ “Meri Saheli” application. CoPs can empower rural women to use the Internet and smartphones for e-commerce.

Offline channel: SHGs (self-help groups)

Several women entrepreneurs are part of SHGs. They come together and discuss group members’ financial needs, aspirations, and challenges, share expertise around their primary occupations, and organize skill-building activities to support each other. This creates a collaborative environment where women learn and grow. These existing institutions, therefore, serve as launch pads for the women entrepreneurs to build localized CoPs, upskill, and scale their businesses. These women also share their success stories and help other women in their community use technology to benefit their businesses.

For instance, during MSC’s fieldwork with Frontier Markets in Rajasthan, we observed that female BC agents actively promote digital transactions on e-commerce platforms and at BC agent points.

Additionally, SHGs provide a platform for financially and digitally proficient women to build their peers’ capacities and offer guidance. For example, Frontier Markets has a strong network of Sahelis in rural Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, which builds rural women’s capacities to place orders on e-commerce platforms and conduct person-to-person (P2P) and person-to-merchant (P2M) digital payments. These women entrepreneurs’ efforts catalyze the businesses of other women entrepreneurs through technology-driven tools and platforms.

The use of community spaces for offline channels

Although CoPs are a stepping stone where women entrepreneurs share lessons with each other, social constraints deter women from gathering in common places. However, women can overcome social constraints and engage in SHG activities when they generate income for the household, provide access to financial services in the community closer to home, and build their identity. Community gatherings in the panchayat office, the primary health center, and schools, among others, can emerge as a channel through which women teach each other how to use e-commerce platforms and conduct digital payments.

Online channels: A potent option to drive CoP

CoP thrives on knowledge sharing and peer learning. Besides SHGs, where women share information in person, digital platforms also provide women with a channel to share information and learn from each other.

Many rural women often use digital applications, such as WhatsApp, YouTube, SMS, and phone calls. A few also use e-commerce or social commerce platforms, such as Amazon, Flipkart, Meesho, and the “Meri Saheli” platform, to buy products independently or with Saheli’s assistance. These self-initiated and assisted transactions clearly demonstrate the use of technology and the key role technology plays to grow their business and build awareness in their community. The following section outlines some platforms we see in action on the ground.

Virtual groups, channels, and chatbots on WhatsApp encourage knowledge sharing and absorption. Geography-specific WhatsApp groups and channels at the SHG or CLF (cluster level federation) level create a platform for women who want to learn how to conduct digital payments and buy and sell products on e-commerce to exchange information regularly. For instance, Frontier Markets encourages engagement among Sahelis and rural women through WhatsApp groups, where they learn about digital payments and advanced agricultural inputs, such as climate-resilient seeds, liquid fertilizers, and animal nutrition.

Platforms, such as Facebook, Meta, and YouTube, equip rural women with diverse skills, such as digital payments, vocational education, and farming. This strengthens their employability and income-generating potential. Moreover, platforms, such as Meesho and the “Meri Saheli” application, enable rural women to access essential household products conveniently. Through these platforms, rural women gain familiarity with digital payment modes, such as UPI (Unified Payments Interface) and QR (quick response) code-based systems (PhonePe, Paytm, and Google Pay). This streamlines their experience to conduct digital financial transactions and build their digital footprints.

The way ahead

CoP initiatives through offline and online channels can help rural women like Sarita develop their financial and digital proficiency and bridge the digital divide. Tapping into the local leadership’s potential and skill sets of financially and digitally proficient women can develop rural women’s capacity to use e-commerce. With an active CoP and willing service provider, many women like Sarita can access larger markets, diversify their income streams, become economically empowered, and enhance their financial and digital literacy.