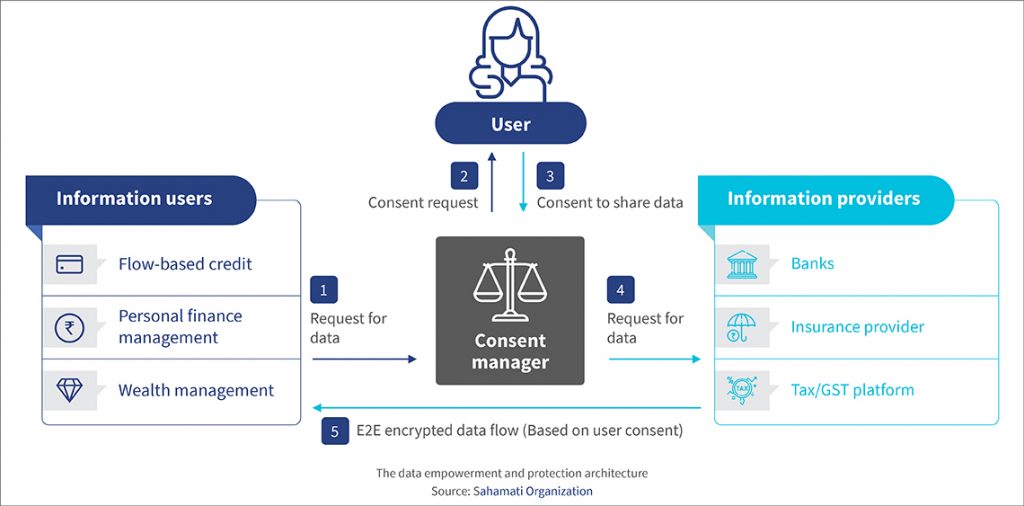

Our previous blog examined how the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) and account aggregators (AAs) could disrupt India’s banking and financial ecosystem. DEPA and AAs can also empower people from the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segment by enabling them to use their data and access better financial services. DEPA intends to democratize individuals’ data using a consent-based framework and allow the movement of trusted data between service providers with customer consent.

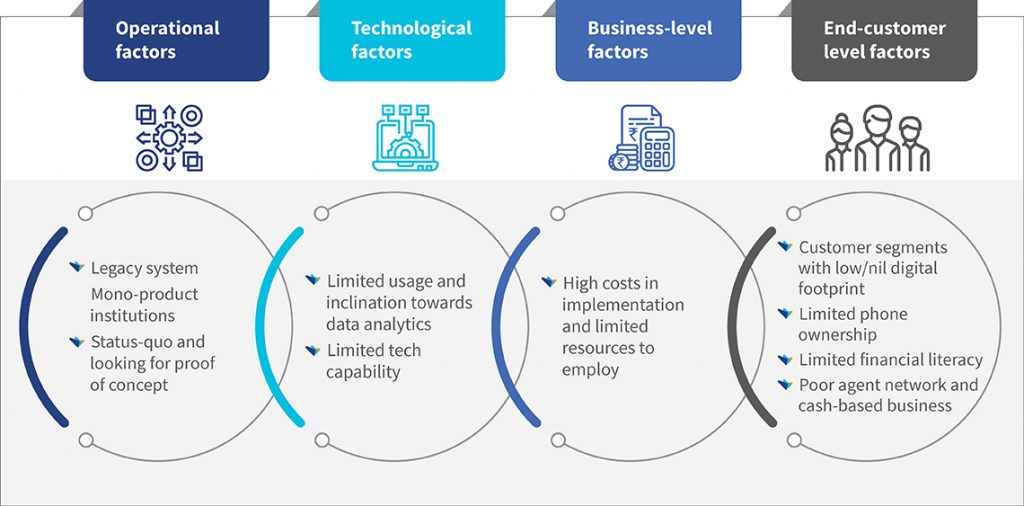

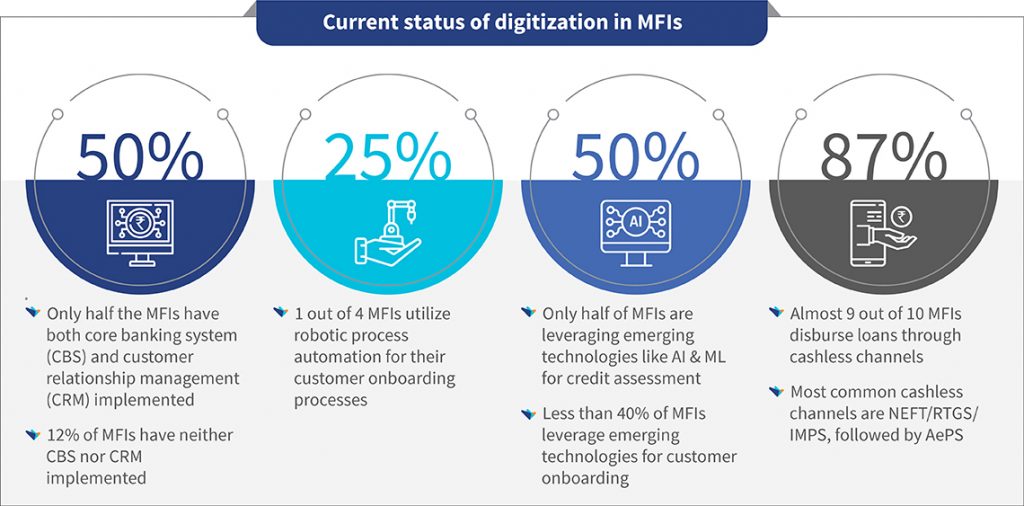

While DEPA is set to revolutionize the Indian financial ecosystem, financial institutions like MFIs may not find onboarding this framework “appealing” or “easy.” Our previous blog discussed the challenges microfinance institutions (MFIs) face while adopting DEPA. A recap of our previous blog:

Key factors hindering DEPA adoption by microfinance-based lending institutions

Some of the critical challenges above may take some more time to resolve. These include the uniform regulation of all forms of MFIs and the increased digital footprint of customers. With the increasing digitization of payments in India, more people will join the digital ecosystem.

MFIs will need to find ways to overcome the remaining challenges and subsequently adopt the DEPA framework.

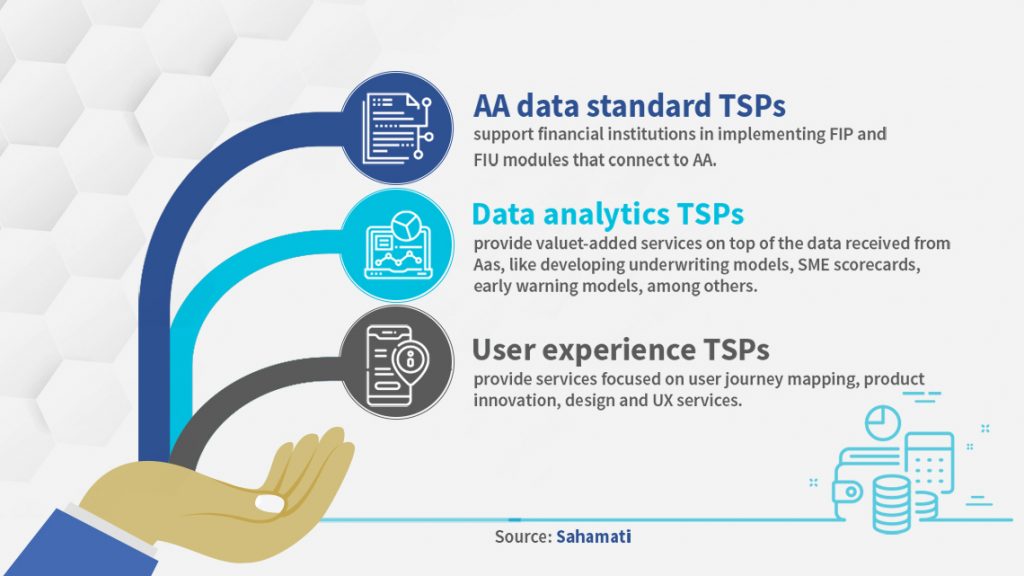

The role of emerging FinTech players is critical. The AA ecosystem brings together technology service providers (TSPs) that support financial information providers (FIPs) and financial information users (FIUs) to use the AA ecosystem through their tech infrastructure and data analytics capabilities.

A critical link in the DEPA framework is the nonprofit Sahamati, a collective of account aggregators that drives open banking in India. It allows individuals and small businesses to share their data with a third party, acting as a common platform to capture customer financial details in one place.

Sahamati has classified TSPs into three different categories based on their offerings:

As shown above, “AA data standard” TSPs can help MFIs initiate and implement the FIP and FIU modules. Whereas “data analytics” and “user experience” TSPs can provide value-added services to the institutions. These TSPs can help MFIs gradually embrace the available customer data and use it efficiently.

For any MFI, how do these TSPs score higher than any regular data analytics company?

A regular data analytics company focuses on the “data processing” part of the value chain, which means the MFI remains responsible for “data sourcing” and “data consumption.” For example, an MFI collects the customer data like bank statements from borrowers through documents or images and stores it in its system from which the data analytics company reads the data. After analysis, the results are stored in a database where the MFI can view or use them for further processing. Moreover, most data analytics companies offer generic analytics platforms. This means that MFIs must engage with these companies actively to decide the analytics they must carry out on the data. Many MFIs do not know this. Companies with niche analytics solutions often do not offer the flexibility of matching MFI needs, which differ significantly from other lenders.

MSC is the technical partner alongside CIIE.CO in the FI Lab of Bharat Inclusion Initiative. Finarkein is a promising TSP FinTech in this cohort.

MSC is the technical partner alongside CIIE.CO in the FI Lab of Bharat Inclusion Initiative. Finarkein is a promising TSP FinTech in this cohort.

How does Finarkein, a TSP in the AA ecosystem offer solutions for MFIs through its Flux platform?

Finarkein offers an end-to-end solution that has the flexibility of customization based on MFIs’ needs. The solution offers incremental change in the MFI business model instead of causing a wider disruption. For example, most MFIs today lack technological processes and rely on manual work for customer interaction, application, fulfillment, and post-servicing. Their workforce is familiar with documents. To support them, Finarkein has built a solution called “Flux” that fetches data from AA, processes it, and converts it into an easy-to-understand PDF file that the MFI workforce can use to act upon. It is curated primarily for technologically laggard NBFCs to encourage them to adopt the AA ecosystem. Flux allows Finarkein to integrate the MFIs with new technology while guiding them toward wider digital transformation.

Source: Sahamati—shows an increasing list of TSPs that help financial institutions embrace the AA framework

Onboarding as an FIU does not require MFIs to make any technological changes as Finarkein provides the technology. The only support needed from the MFI is to help the customer approve consent requests via calls or in-person engagement—Finarkein sends the customer an SMS containing the consent link. If a customer does not have a smart device, then consent can be taken on the MFI agent’s device too. In the future, consent approval can be done on WhatsApp or through phone calls too.

Finarkein can share output reports over email, which MFIs can use for underwriting. In this journey, the MFI does not build any new technical capability. Finarkein offers an end-to-end working solution that helps the MFI become an FIU and source data. Finarkein has also been working on a portal through which MFI agents can share the consent link with customers, further eliminating the need for technical integration. The company has structured it as a flexible pay-per-use model from a commercial perspective.

With the benefits that TSPs like Finarkein provide, an MFI can stop worrying about daunting technological integrations and focus more on its business.

How do TSP services further support the MFIs to build decisions based on data?

Building an early warning signal system through data analytics

Delinquency costs remain a significant pain point for MFIs. TSPs can help traditional MFI lenders manage their delinquency better with data analytics. Emerging FinTechs in the lending space use data analytics extensively to understand their portfolios and draw deep customer insights. TSPs can help traditional MFIs enhance operational efficiency by reducing customer monitoring costs, customer acquisition costs, and NPAs.

Early warning engine for debt collections using alternate data

Most MFIs’ lending portfolio is unsecured. While MFIs follow regimental processes, they lack clear insights into the borrower’s loan repayment intent. Once MFIs are onboarded onto the AA framework as an FIU, TSPs can enhance the prediction engine by importing additional customer data from other sources. Hence, integrating with AA platforms will facilitate building effective risk management solutions for MFIs.

Bounce alert reports using alternate data

The customer signs up for electronic loan repayment through the National Automated Clearing House (eNACH) for repayments. The bounce alerts system will flag if the customer has any pending dues. TSPs can help MFIs implement AI/ML-based models to study customers’ payment patterns of their loan products.

Reducing operational costs and increasing efficiency through better visualization

This is an area where TSPs can play a crucial role through their data visualization expertise. TSPs can support MFIs by analyzing customers’ pre-existing data and presenting it succinctly. They can support MFIs by building dashboards on internal and external data.

Dynamic collection scores using alternate data from other institutions and CRM data

This feature can automate and optimize the repayment collections management process, which would improve collection efficiency, minimize the risk of NPAs, minimize write-offs, and improve customer relationships, among others. Dynamic collection scores will also help reduce loan repayment collection costs due to the automated process.

AI/ML-driven personalization for customers

TSPs can provide MFIs with an AI/ML-powered platform to facilitate hassle-free and remote customer onboarding, customer screening, additional customer benefits through different interest rates, and other benefits. Moreover, it can offer the MFI better product management tools within a secure environment. MFIs can use natural language processing (NLP) through this platform to address the language barrier between new-age technology and their customers. TSPs can help develop a voice-assisted user interface for the MFIs’ application to ensure hassle-free usage by their LMI customers.

Cross-selling and upselling of credit-based products

MFIs can use TSPs to help upsell or cross-sell other credit-based products to existing or new clients. Backed by extensive data and behavioral analytics, TSPs can suggest that MFIs target specific customers to cross-sell or upsell third-party products like buy-now-pay-later facilities and credit cards.

MFIs need to examine the benefit that the DEPA ecosystem can offer. India Stack’s consent layer can potentially reduce costs and enhance the customer value proposition. It is time for MFIs to adopt data-intrinsic approaches to function efficiently in the digital age and drive financial inclusion. This is where the TSPs can come in handy.

Linking this back to where it started—we return to the story of lighting homes with electricity way back in 1882. After electricity entered homes and factories, many other inventions revolutionized the way we live, such as the induction motor, which transformed industries and further led to the power washing machine (1907), vacuum cleaners (1908), and household refrigerators (1912). These inventions led to the greater adoption and demand for electricity. The account aggregator framework will likely follow a similar path where financial service providers will be more interested in adopting it with evolving use-cases. Till then, entities like TSPs will continue to simplify the onboarding of FSPs onto the AA framework.

Support from the

Support from the

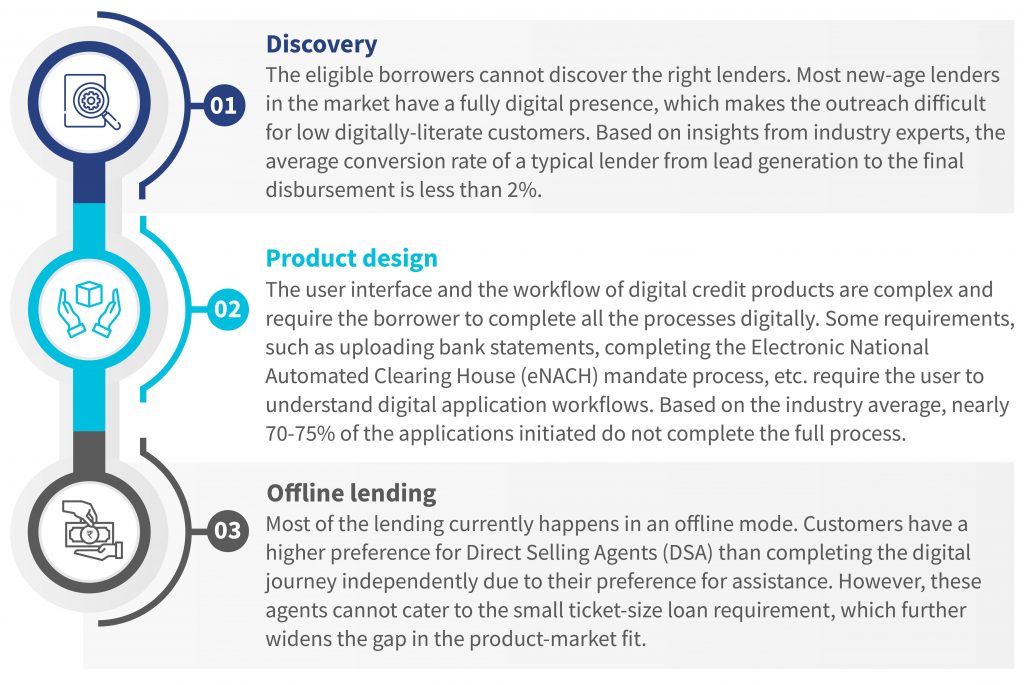

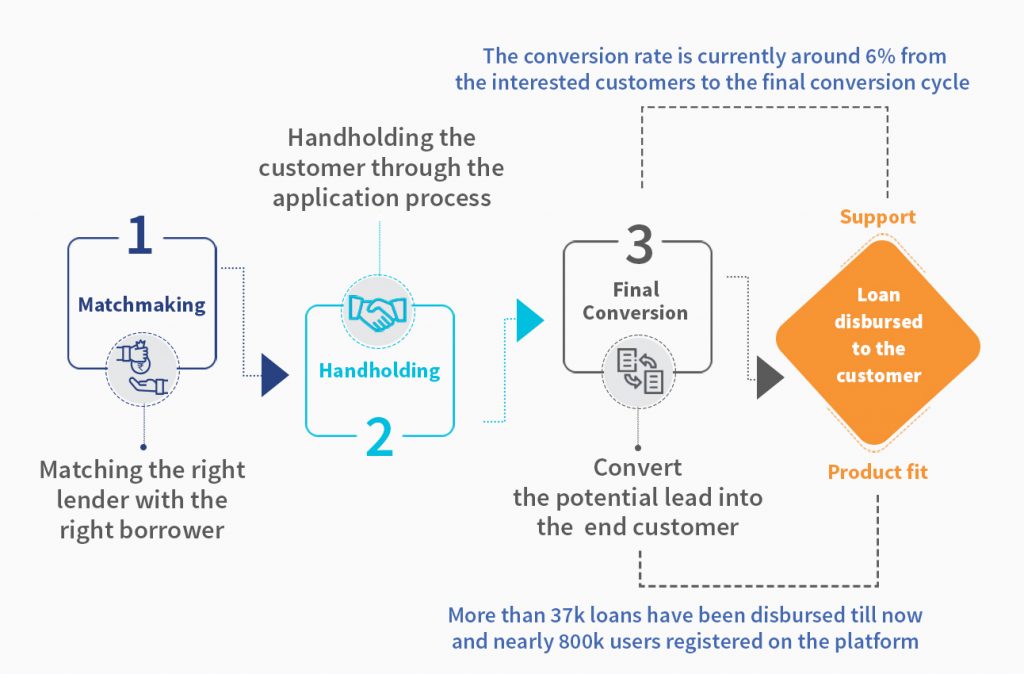

These challenges compelled IIM Indore alumnus and Chartered Financial Analyst

These challenges compelled IIM Indore alumnus and Chartered Financial Analyst