Digital transformation continues to change how customers in Indonesia interact with companies and authorities and how they experience business relationships. Yet, it has also led to a wide range of frauds. A recent article highlights that in 2021, authorities have shut down more than 1,800 unlicensed online FinTech lenders and social media applications. The government has blocked 4,875 illegal loan accounts since 2018.

Customers are often the ones to initiate the push to use digital channels. Interestingly, they have changed their habits and expectations considerably. Customers are also now more likely to voice their complaints, and rightly so. The Indonesian Consumers Foundation (ICF) in 2020 revealed a 50% jump in consumer complaints from the previous year. ICF also revealed the major categories of consumer complaints in 2020 have remained constant for five years—complaints against financial service products consistently comprised 34% of all complaints. The complaints across other sectors included e-commerce at 12.70%, telecommunications at 8.30%, electricity at 8.20%, and housing at 5.70%.

As digitization and the use of social media increases, the risks consumers face and the channels they use to air grievances have increased. Similarly, financial institutions also face several new risks due to the extensive use of innovative technologies and operational models. These include risks related to data privacy, cybersecurity, agent, and channel. Regulators are therefore required to enhance and strengthen consumer protection and market conduct supervision. Regulators have now adopted different supervisory technology (SupTech) solutions to supervise the sector and mitigate these risks. Various countries have used tech-enabled regulatory reporting, automated consumer grievance resolution, and non-traditional approaches like social media monitoring and consumer sentiment analysis.

Supervision in a constantly changing digital world

Indonesia is the world’s fourth-most populous country with 274 million people, a relatively young population, and a median age of 28.7 years. Internet penetration in the island nation stands at 67%, which offers fertile land for digital transformation and offers FinTechs the chance to grow. According to a new report produced by FinTech News Singapore, Indonesia is home to 322 FinTech companies, besides 125 registered but unlicensed online lenders. The sector is expected to continue to grow. Besides new players, incumbents are also attempting to digitize their processes and benefit from technology.

Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK), Indonesia’s financial services authority, wants to explore novel approaches to supervise the digitized delivery of financial services, especially for consumer protection. OJK supervises more than 2,500 financial institutions, including banks, multi-finance companies, insurance companies, FinTechs, pension funds, and capital market players. With such a wide range of institutions under its supervision and the rapid growth in digital financial services, OJK seeks to transform its systems. The transformation would allow OJK to get a more holistic picture of all consumer complaints and gauge the effectiveness of internal dispute resolution procedures implemented by the service providers.

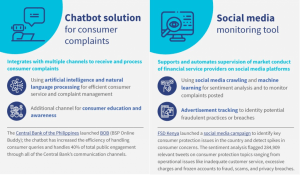

Some countries with a high penetration of digital finance technology have also experimented and implemented RegTech and SupTech solutions. The Central Bank of the Philippines has implemented a chatbot solution for customer complaints. It enables the central bank in the Philippines, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), to address queries and complaints automatically, manage the structure and flow of conversations based on sector expertise and historical data, and use data and insights gathered from the chatbot for oversight and policy formulation. The chatbot has been increasing the efficiency of handling consumer queries in banking, financial services, and insurance.

In 2016, the Central Bank of Nepal (NRB) designed a web portal to act as a single data point for submitting reports from FSPs. The portal would also support the varied technical abilities of the country’s FSPs. Digitizing its regulatory reporting infrastructure has streamlined what data NRB can collect and make available and how, allowing NRB to share more raw data and reports publicly. Digitization offers many benefits in Nepal, including market intelligence for FSPs and overall intelligence on the state of financial stability, financial inclusion, and market conduct.

What dynamic solutions are in store for Indonesia?

OJK realized the potential of emerging technologies and started an initiative to upgrade its consumer protection practices. OJK’s consumer handling unit shows that OJK received 82,718 complaints in 2018, which increased to 117,099 complaints in 2019, a significant increase of around 40%. OJK developed a chatbot called Kontak 157 and a consumer protection portal, the Aplikasi Portal Perlindungan Konsumen (APPK) platform. Both enabled quick and automated registrations to handle and process these complaints more efficiently. The chatbot platform has already seen uptake among consumers. The chatbot channel and email response system received on average 51,000 complaints monthly.

OJK wants to explore opportunities to use modern technologies to analyze data in real-time and thus identify potential market misconduct or growing risks to financial stability efficiently and accurately. This entails using big data analytics, machine learning, text mining, and other technologies to supervise consumer complaints and provider conduct proactively. The graphic below outlines solutions in the pipeline to be prototyped.

(Links: BOB, FSD Kenya’s social media campaign )

- Automated chatbot for the OJK website for consumer education and inquiries or complaints: The chatbot will be used primarily for:

- Customer service and complaint management: The chatbot will address customer queries or complaints related to interactions with financial institutions and complaints about services or products of a specific service provider or financial institution. The chatbot will use AI and NLP to enhance customer experience and improve the overall resolution process.

- Customer education and awareness: The chatbot will assist users (through FAQs or the chat function) with consumer rights regarding financial services adoption, usage, grievance resolution, protection of data, code of conduct, or fair practices code. It will also have standard information on financial products and services—do’s and don’ts, pricing criteria, product features, and benefits.

- Social media monitoring tools using social media crawling and machine learning for sentiment analysis and advertisement tracking would identify potential fraudulent practices or deviations from OJK guidelines. This solution will automate supervision by monitoring complaints posted on social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. It would also automatically monitor advertisements that financial institutions post on social media, newspapers, and electronic media.

Through the adoption of these solutions, OJK’s clear objective is better regulatory oversight. Some of the critical outcomes that OJK intends to have through these solutions are:

- Reduced turnaround time for resolving issues through proper prioritization and categorization, after which authorities and officials can take necessary measures;

- Effective identification, tracking, and reporting of any deviations from regulations and collection of relevant evidence;

- Detection of fraud and misinformation.

Key performance indicators (KPIs) will be captured during the prototyping phase by OJK and MSC to provide some measurable outcomes for adopting these solutions. Some of the metrics will be around the user engagement rates, turnaround times, and accuracy of complaint resolutions.

Getting the ball rolling

Over the next few months, OJK and MSC will work with the selected vendors to develop and prototype the solutions. The prototyping phase for the sentiment analysis will cover one key sub-sector. The chatbot will be tested with a limited audience. Still, it will ensure all integrations and channels for consumers are functioning smoothly. This testing phase is expected to last for six months and help us customize the solutions to the specific requirements for OJK as a regulator. The prototyping will include adding appropriate context, adjusting to ensure the correct terminologies and nomenclatures, and calibrating for other biases.

During this phase, MSC will document and share lessons from the steps of implementation, the impact and progress against our set KPIs, and the key takeaways for others looking to implement similar solutions. Stay tuned as we publish these updates.

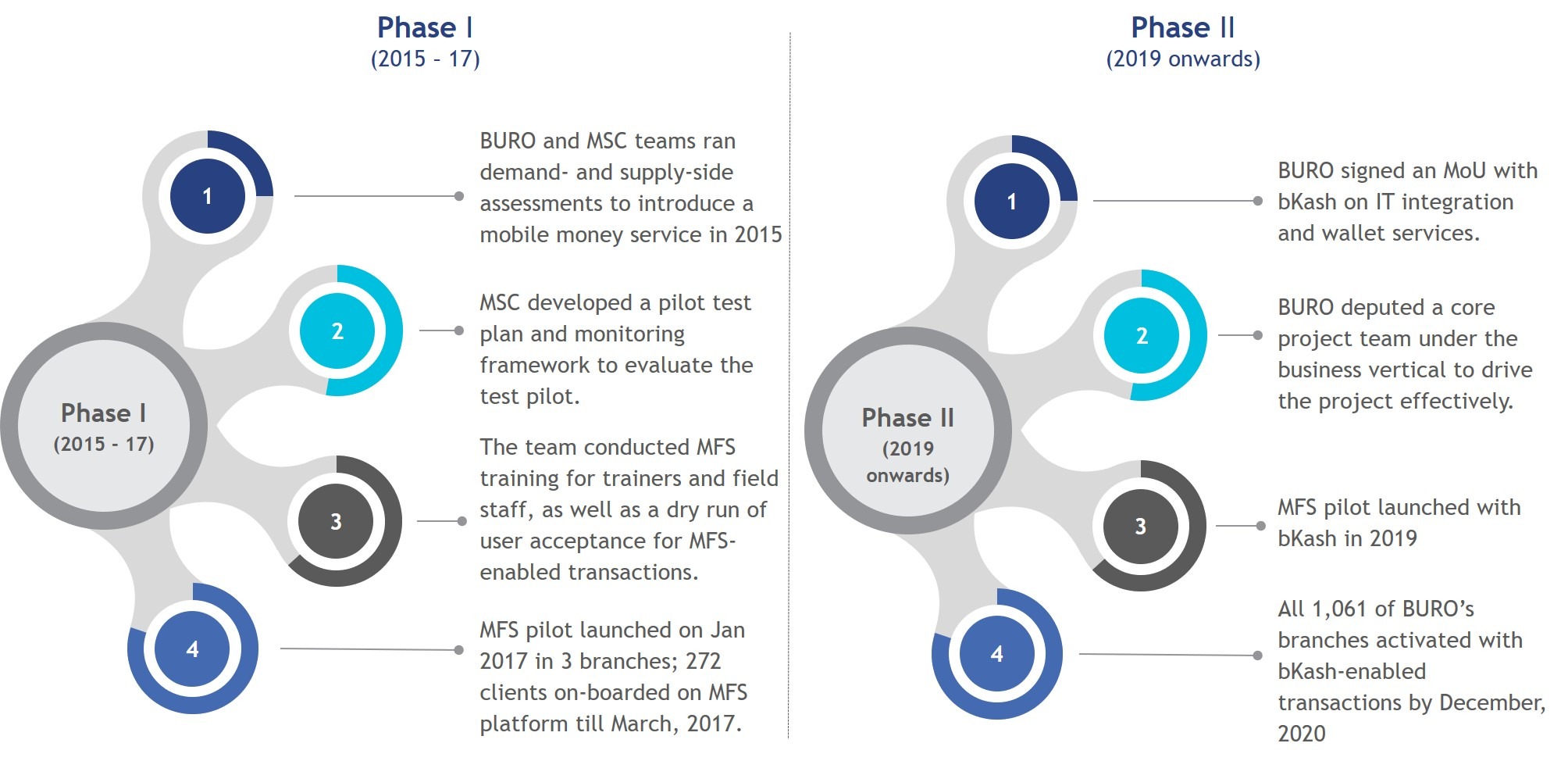

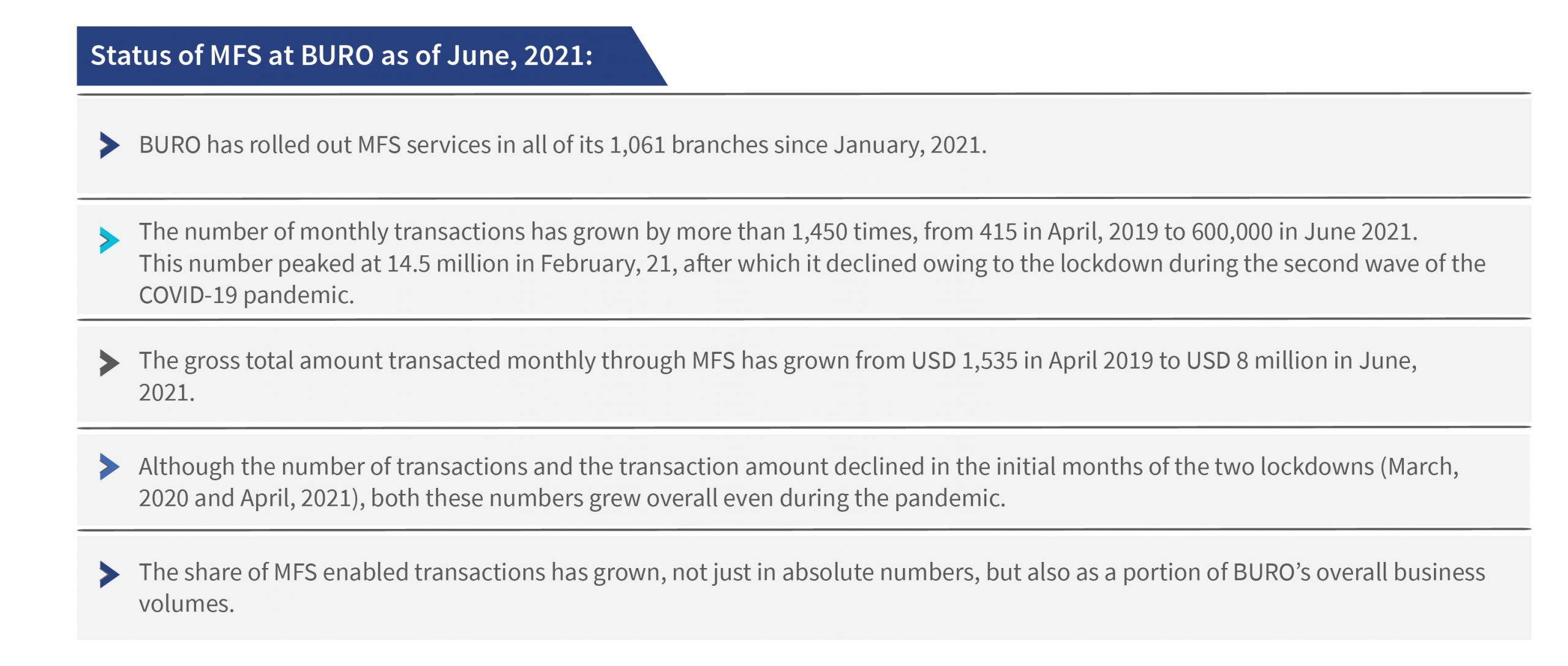

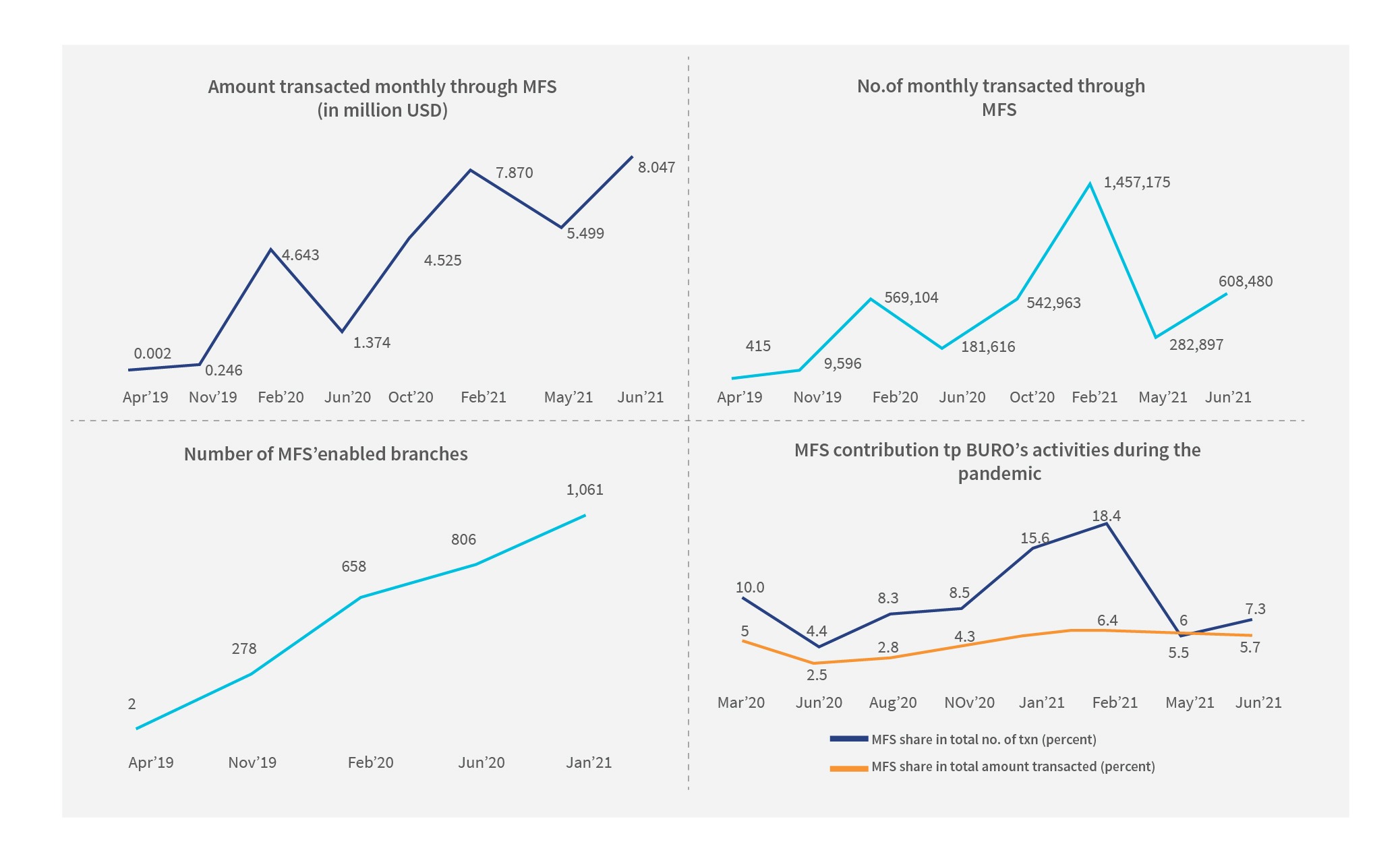

Small shop-owner Ruksana Begum has been a member of BURO for seven years. She used to repay her loans and save in cash at the weekly center meeting. Ruksana had to shut her shop to attend the meeting. So when BURO introduced the option of paying using mobile financial services (MFS), she switched immediately. Ruksana believes that besides saving time, using MFS protected her during the pandemic. Through MFS, she could avoid physical interactions to repay her dues and receive remittances from her husband, who works in Qatar.

Small shop-owner Ruksana Begum has been a member of BURO for seven years. She used to repay her loans and save in cash at the weekly center meeting. Ruksana had to shut her shop to attend the meeting. So when BURO introduced the option of paying using mobile financial services (MFS), she switched immediately. Ruksana believes that besides saving time, using MFS protected her during the pandemic. Through MFS, she could avoid physical interactions to repay her dues and receive remittances from her husband, who works in Qatar.

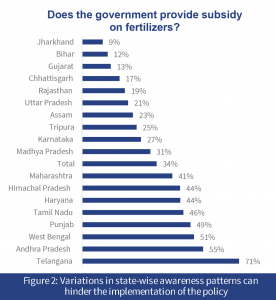

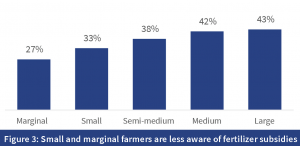

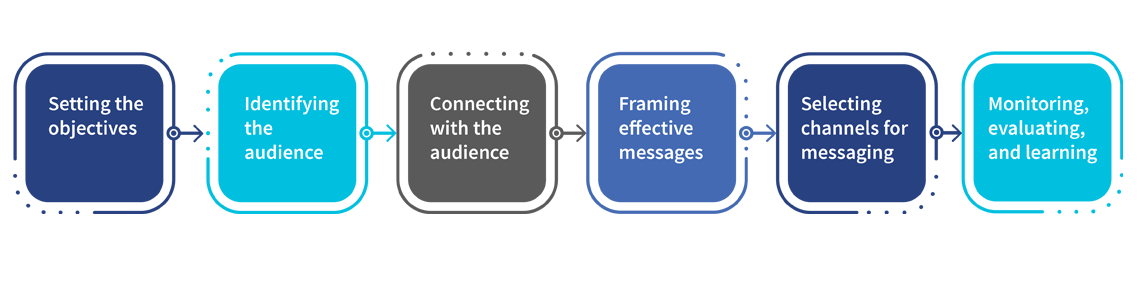

Before the government implements a shift in policy, it must consult stakeholders, communicate with them effectively during implementation, and address their concerns.

Before the government implements a shift in policy, it must consult stakeholders, communicate with them effectively during implementation, and address their concerns.