This blog is about a FinTech startup from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which receives support from some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world—the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

Ravi Varma, an auto-rickshaw (tuk-tuk) driver from Bengaluru, could not save regularly. However, since the COVID-19 lockdown, he discovered that regular savings could compensate for the volatility of his income. This pool of savings could also take care of his family in an emergency. Since June 2020, Ravi started saving up to INR 100 (~USD 1.35) daily with Lakshya and accumulated more than INR 10,000 (~USD 135) by March 2021 for medical emergencies. He had set himself a goal of INR 15,000 (~USD 202) for an emergency. Regular savings helped him to achieve his goal within few months. Auto drivers like Ravi Varma lack regular savings habits and fall prey to loan sharks to meet their daily expenditures.

Ravi Varma, an auto-rickshaw (tuk-tuk) driver from Bengaluru, could not save regularly. However, since the COVID-19 lockdown, he discovered that regular savings could compensate for the volatility of his income. This pool of savings could also take care of his family in an emergency. Since June 2020, Ravi started saving up to INR 100 (~USD 1.35) daily with Lakshya and accumulated more than INR 10,000 (~USD 135) by March 2021 for medical emergencies. He had set himself a goal of INR 15,000 (~USD 202) for an emergency. Regular savings helped him to achieve his goal within few months. Auto drivers like Ravi Varma lack regular savings habits and fall prey to loan sharks to meet their daily expenditures.

The frequent reliance on informal credit for small expenses pushes this segment into debt traps. They need access to flexible and customized savings products to save as per their cash flows.

The light-bulb moment

Lakshya started with a mission to improve the financial health of the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segment by using digital platforms to deliver financial products and literacy to build traction.

Founder Nishant Kumar, a development sector professional who has also worked at MSC, has seen the silent revolution in financial inclusion for a decade. He observed that formal financial services, especially savings, have remained low despite a massive macro-economic push for financial inclusion in India. Financial providers neither emphasized nor innovated around savings due to the lower margins and challenges in digital distribution to the target segments. In January 2020, Sonal Agrawal joined the Lakshya team bringing her rich experience in financial inclusion from her stints at MSC, the World Bank, and the Indian government’s National Rural Livelihoods Mission.

Founder Nishant Kumar, a development sector professional who has also worked at MSC, has seen the silent revolution in financial inclusion for a decade. He observed that formal financial services, especially savings, have remained low despite a massive macro-economic push for financial inclusion in India. Financial providers neither emphasized nor innovated around savings due to the lower margins and challenges in digital distribution to the target segments. In January 2020, Sonal Agrawal joined the Lakshya team bringing her rich experience in financial inclusion from her stints at MSC, the World Bank, and the Indian government’s National Rural Livelihoods Mission.

Lakshya began its operations on 15th August 2020. Around 80% of India’s working population is engaged in the informal sector in micro or small enterprises or works independently. Only a handful of FinTechs has worked directly with them due to the high cost of aggregation and trust-building. Nishant identified this as an opportunity to drive impact by improving the financial inclusion metrics beyond access. While initially, Lakshya dealt with savings, it progressed to include insurance and credit over time.

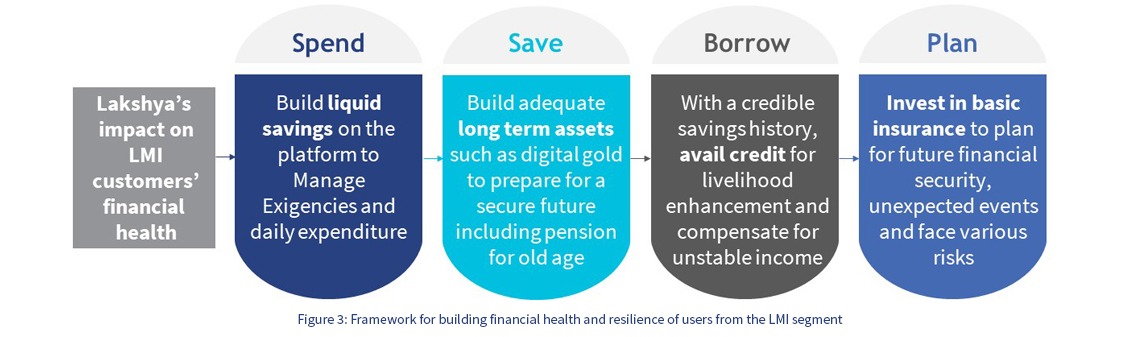

Lakshya has built a framework (Figure 3) with the following five pillars to focus on improving financial health:

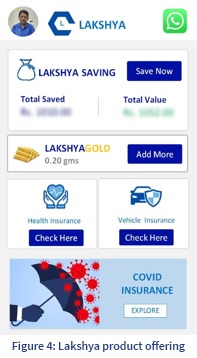

Additionally, Lakshya also nudges customers to enroll in suitable government schemes like Jan Suraksha Yojana (Figure 4). It supports them to complete income tax returns and thus builds the income history necessary to access credit from formal institutions. To begin with, it started by focusing on the first two pillars—manage expenses and build savings.

Initially, Lakshya identified auto-rickshaw drivers in Bengaluru as their target segment because:

- They form a large group with nearly 400,000 drivers

- They are the primary financial decision-maker of the family

- Most of them own smartphones and are familiar with digital payments

- They have a bank account that helps them sign up for channels like UPI

- They are aggregated at digital platforms or unions, therefore easily accessible to Lakshya and can provide “word of mouth” referrals

After understanding this segment’s financial need of providing credible sources of savings, Lakshya developed a solution that would meet their need for customized financial products. Lakshya plans to build on this initial work to transform it into a ubiquitous platform for other segments.

After understanding this segment’s financial need of providing credible sources of savings, Lakshya developed a solution that would meet their need for customized financial products. Lakshya plans to build on this initial work to transform it into a ubiquitous platform for other segments.

Lakshya has since onboarded semi-organized artisans, weavers, and gig workers on its platform. By May 2021, despite two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the LMI segment saved more than INR 4 million (~USD 53,880) and bought more than 500 health insurance policies on the platform.

Lakshya’s unique pitch

Lakshya offers its users relevant and flexible savings products on a digital platform. It allows users to make small-ticket savings, as low as INR 5 (~USD 0.07) a day, to help build a daily savings habit. Regular savings coupled with basic insurance reduce dependence on informal credit and the risk of debt for medical exigency and household expenditures.

Lakshya’s team designed the platform with a straightforward user interface (UI) to ensure users unfamiliar with digital payments find the platform user-friendly. It harnessed existing technologies, such as UPI, wallets, and mobile banking to reach its target segment. To plan for external shocks and build assets, Lakshya partnered with financial institutions, such as ICICI Bank and Dvara SmartGold.

Lakshya works with local aggregators – associations, unions, and social enterprises, to onboard their target segments. These partners typically have a local presence and work with the community, for example, artisans and drivers. By aggregating them on a common platform, Lakshya builds large homogeneous communities to serve similar financial needs and reducing onboarding costs. Large groups will also allow Lakshya to curate products addressing the specific needs of a particular segment, such as health insurance, working capital credit.

The impact on LMI segments

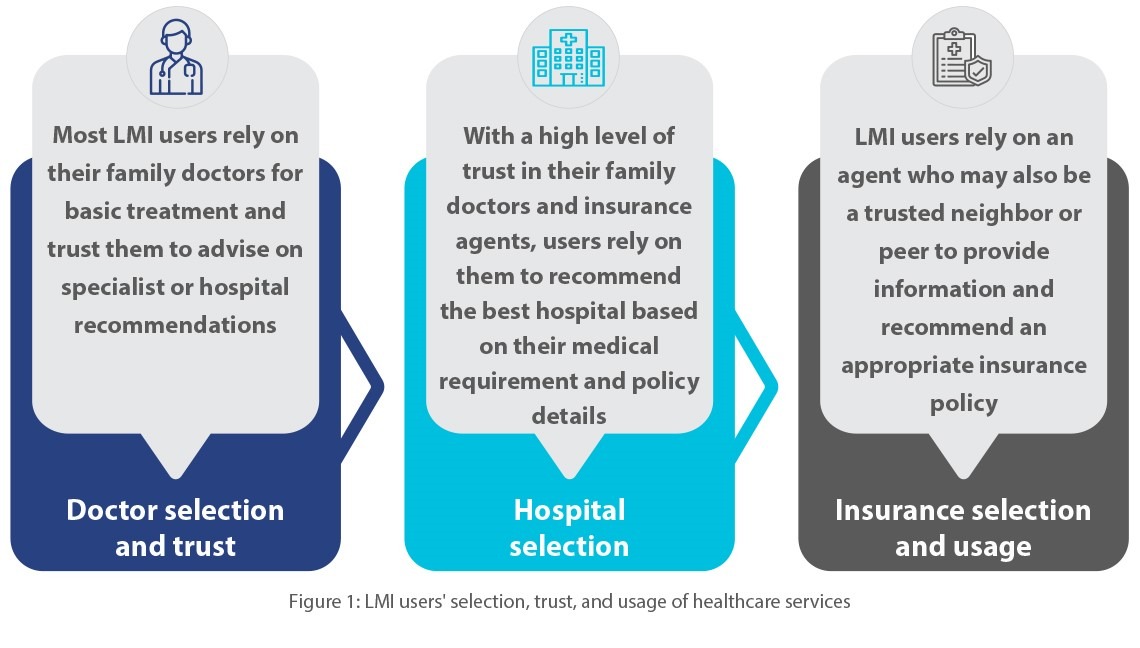

Many of Lakshya’s customers have had bank accounts for years, but they remain dormant. With Lakshya, customers can develop a habit to save or insure, which will help build a credible savings history that allows them access to formal credit products in the future. Lakshya reinforces and normalizes savings behavior within the LMI community, as they rely on “word of mouth” for credible information on financial management.

The roadblocks

All of Lakshya’s customers are not confident smartphone users. Lakshya makes it easier for such customers to use its services by offering transaction assistance at their office and over the phone and sharing app-tutorial videos on YouTube. In Bengaluru, users from LMI segments receive support from their associations or Lakshya staff while conducting initial UPI transactions.

Previous instances with fraud and complicated insurance terms and conditions have eroded trust among many users. Lakshya simplifies the product’s key features and shares them with users in the local language to improve uptake and usage.

The FI Lab support

The Centre for Innovation Incubation and Entrepreneurship (CIIE) and MSC (MicroSave Consulting) conducted boot camps and diagnostic sessions with Lakshya.

Nudging consumers toward savings is challenging, especially with the prevalence of easy-to-access informal credit. Auto drivers frequently rely on credit to pay mandatory vehicle insurance. However, Lakshya wanted to challenge this existing practice and provide an alternative recurring deposit option to build that corpus. MSC supported Lakshya in the journey to nudge their clients towards regular savings.

MSC segmented users into different personas based on extensive analysis of Lakshya’s user data and in-depth qualitative field research. This will help Lakshya work with them based on their different financial habits and journey with various financial products that build their economic well-being. MSC also uncovered the impact that Lakshya has created on the financial health of the households of their 3,500 unique users. Previously, Lakshya’s users relied on informal credit to manage their daily household expenses. With Lakshya, they can create a savings pool to manage expenses and emergencies.

Creating opportunities amid the COVID-19 crisis

Despite fintech financial products taking a hit during the pandemic, Lakshya reactivated and instilled savings behavior among its dormant clients. Lakshya nudged them to save in small denominations regularly during the first wave of the pandemic. In addition, during the nationwide lockdown from March 2020 to June 2020, Lakshya onboarded 800 new customers by working with partners such as gig platforms and artisan aggregators.

During the disastrous second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, users who built a corpus could better manage their loss of income. They could maintain their financial health since they had planned, accessed, and used suitable financial products.

The path ahead

Lakshya will continue to target homogenous segments — drivers, security guards, and gig workers. Building on its vision of improving financial health for the LMI segments, Lakshya will focus on digital communication to impart product literacy to empower users.

In the future, Lakshya intends to provide services, such as financial advice, insurance, and small-ticket credit products, to become the one-stop shop for financial health.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that make a difference to underserved communities. These startups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat

Devleena Bhattacharjee, the founder and CEO of Numer8, has a background in data science. A serial entrepreneur who used to develop data solutions primarily for urban customers, Devleena was keen to use her skills to address more significant global issues, such as climate change, disaster recovery, and livelihood resilience.

Devleena Bhattacharjee, the founder and CEO of Numer8, has a background in data science. A serial entrepreneur who used to develop data solutions primarily for urban customers, Devleena was keen to use her skills to address more significant global issues, such as climate change, disaster recovery, and livelihood resilience.