Youth unemployment in Africa is a present issue in the continent owing to the rapid population growth and lack of matching sufficient job opportunities. The gig economy has the potential to decrease unemployment rates amongst youth, through providing an avenue to meaningful engagement with the formal economy

Blog

Resolving challenges for digital credit with segment-specific vulnerabilities

Stanley is a 35-year-old trader who sells second-hand shoes in one of the largest open-air markets in Nairobi. He makes good profit during peak hours and often reinvests the amount into his business. At times when the profits drop and become irregular, Stanley often requires a line of credit to stay afloat. On average, he borrows USD 300 per month from digital lenders to replenish his stock. He repays the loans on time to avoid a reduction of his loan limit and being negatively listed.

Stanley is a 35-year-old trader who sells second-hand shoes in one of the largest open-air markets in Nairobi. He makes good profit during peak hours and often reinvests the amount into his business. At times when the profits drop and become irregular, Stanley often requires a line of credit to stay afloat. On average, he borrows USD 300 per month from digital lenders to replenish his stock. He repays the loans on time to avoid a reduction of his loan limit and being negatively listed.

Stanley is just one among the many digital borrowers who have improved their livelihoods successfully through digital credit. Seven years since digital credit emerged, almost 6 million Kenyans either have used the service or continue to use it. Yet the question remains—is the reach of digital credit wide enough to help all Kenyans who need instant credit? To answer this question, we interviewed a sample of 50 digital borrowers. We used our Market Insights for Innovation and Design (MI4ID) approach to gather insights on the use of digital credit, segment-specific behaviors, adequacy of customer protection, and product awareness.

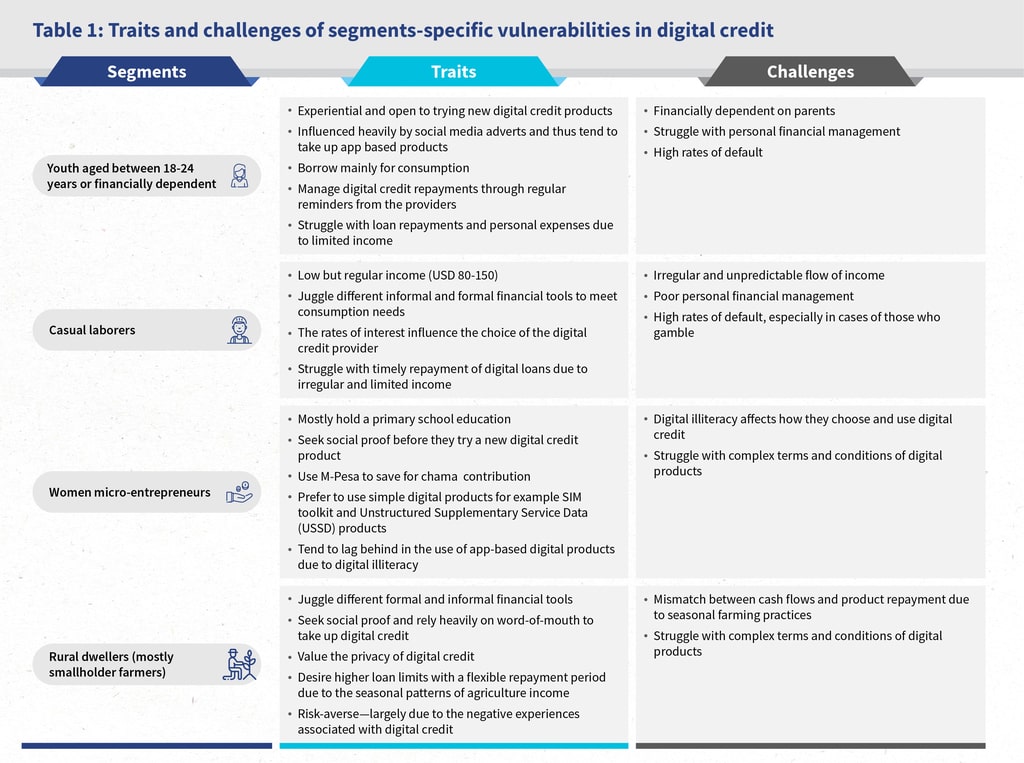

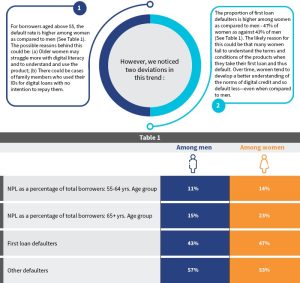

Our research focused on the neglected segments as elaborated in this report “Digital credit in Kenya: evidence from demand-side surveys”. In Table 1, we explore some of the traits and challenges of these segments that have resulted in low to moderate rates of uptake. These segments use nearly half of the total amount borrowed for consumption.

For digital credit to serve the marginalized segments, the lenders may address a few of the options, as listed below:

Appropriate product design

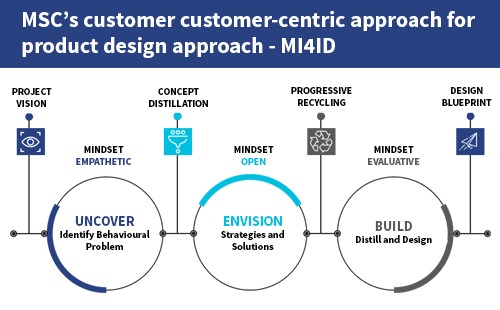

Adopt a customer-centric approach (see figure 1) to develop digital credit products that serve a majority of the segments. This would help avoid further exclusion for segments like farmers and women micro-entrepreneurs. Our MI4ID approach works on the premise that product development goes beyond the traditional process. The approach incorporates the principles of behavioral economics and human-centered design. At MSC, we believe that product development must be a two-pronged process—the generation of market insights, followed by innovation and design.

Figure 1: MSC’s customer-centric approach for product design—MI4ID

Suppliers who already operate at scale should work on more granular customer segmentation and tweak their product products and services appropriately. However, some niche players who are committed to this goal deserve better support, such as DigiFarm, Apollo Agriculture, and AfriKash

Box 1: The case of DigiFarm

In 2017, DigiFarm, an agricultural solution developed by Safaricom, partnered with FarmDrive to develop and launch a loan product. The product had flexible repayment terms that range from 30 to 120 days. As of May 2019, DigiFarm had registered over 1 million smallholder farmers on its platform who have access to digital input credit and harvest cash loans.

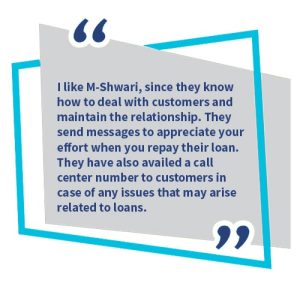

Use of cost-effective digital channels to communicate with the vulnerable segments

When it comes to customer engagement, specific segments, such as the rural people, do not find social media channels to be intuitive. This is because they prefer human interaction. Providers should include at least one channel that features a relatively higher “touch”. For instance, a customer care number introduces a human element that could be used for marketing and collection of loan repayments.

Product marketing as a tool to educate digital borrowers

Nearly all of the digital lenders send emotive marketing messages to potential customers to persuade them to takeloans, as shown in the figure below :

However, the level of financial capacity is inadequate in some segments, such as the youth and casual laborers. They are easily influenced to take up digital loans. To encourage the responsible uptake of digital loans and higher rates of repayment, providers can introduce educational content into their product marketing strategies

Box 2: Case of Pezesha

Pezesha is a peer-to-peer digital marketplace that targets low-income borrowers in Kenya. Its customers have a data wallet that enables them to build and store their digital profile that they can use to access credit from formal lenders. Pezesha also focuses on financial education to promote and encourage responsible financial practices and credit uptake among digital borrowers. Through its solution, Patascore, the company offers financial education content that covers a variety of areas, such as savings and investment, effective debt management, ways to improve one’s credit score, and Credit Reference Bureaus (CRBs) and their role. In the event where a borrower is denied a loan, they receive tips on how to improve their scores and advice to re-apply later.

In just seven years since the advent of digital credit in Kenya, it has displayed a great potential to serve the marginalized segments. The development of more suitable products by the suppliers can prove to be a tremendous step towards the financial inclusion of these segments.

Our report based on our study of the digital credit landscape in Kenya (2019), discusses the changes in the digital credit landscape. It highlights the core challenges, emerging concerns and also goes further to formulate recommendations for both regulators and suppliers to make the delivery of digital credit more responsible and customer-centric. Read it here.

[1] Chama is a Swahili word for group savings

Launch of the digital credit report in Kenya- First English webinar in our series

Speakers from SPTF, MSC and the Smart Campaign discuss the key insights from the analysis of digital credit in Kenya and the recommendations from the newly launched report ‘ Making Digital Credit Truly Responsible’ at the first webinar series on 25th Sept 2019.

DBT and FI in India

Financial inclusion in India received a huge boost, thanks to the PMJDY program, Aadhaar, and the expansion of mobile connectivity throughout the country; but the real catalyst is the country’s digital benefits transfer program.

Where are the women in the digital credit bandwagon? Lessons from Kenya

Seven years since the launch of digital credit in Kenya, women are still disproportionately under-represented among borrowers. Yet they offer immense potential—for providers with the right focus. Just as in many developing markets, the economic participation of women in Kenya is largely concentrated in the informal sector, where women participate in small businesses, farm on small landholdings, and work as laborers, among other professions. The digital avatar of credit is particularly well suited for this segment, as it can address some of the biggest challenges that women entrepreneurs face.

Access to credit is an important tool since economically empowered women are better equipped to achieve their goals. They are able to provide for their families, contribute to society, and advance their own rights. The instant, uncollateralized, and relatively hassle-free nature of availing digital credit makes it an effective tool for women to manage or smooth over emergencies related to income. It has the potential to play a direct role to advance Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE) and further the Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5) of gender equality.

We are excited by the significant opportunity that digital credit offers in the current age, which is characterized by a rapid increase in access to mobile phones. At present, Kenyan women comprise just 37% of the digital credit user base, which amounts to a gender gap of 26%1. The participation of women in the digital credit market is even lower when we consider loan volumes—women borrow only 31% of the total value of digital credit loans1. This presents a significant opportunity for players in the digital credit ecosystem to expand their customer base. Yet gender inclusivity is one area that needs more work.

MSC’s recent study2 on “How to make digital credit truly responsible and transformative” highlights three key insights to make digital credit in Kenya more gender-inclusive.

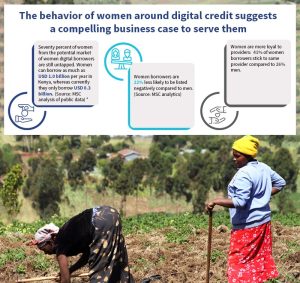

1. Evidence suggests that women are more reliable and loyal borrowers and hence form a strong business case for providers to employ a gender lens.

Our research reveals two interesting behavioural traits of women borrowers:

Figure 1

a) On average, women are less likely to be negatively listed as compared to men (See Figure 1). Women are more anxious about defaults and their consequences. They are also generally more risk-averse in nature. These reasons probably drive them to be extra cautious to repay on time.

b) They are more loyal to a specific brand and prefer to stick to one provider instead of experimenting with different ones3.

Men are more experimental and tend to use a number of digital credit providers while women stick to preferred providers. This indicates a need to tap into this tendency to be loyal to ensure a prolonged business relationship. Among those with multiple digital loans, 41% of women borrowers stick to the same provider, as compared to 26% of men.

The unmet market potential of women, their lower rates of default, and greater loyalty establish a strong business case for providers to onboard more female customers. Variation in reasons for taking digital loans among women indicates the heterogeneity in the segment. Providers have an important opportunity to recognize this heterogeneity of women as a segment and build a strategy focused on them. This strategy may include the design of segment-specific products and intuitive women-friendly digital interfaces along with gender-centric communication, among others. Providers that already operate on a large scale have a great opportunity to offer differentiated services for women.

Niche players who are committed to this goal also deserve greater support from the investors and regulators.

2. The organization of cost-effective digital communication campaigns with a human face is the key to attract more women customers

The study on “Digital Credit in Kenya: Evidence from demand-side surveys” indicates that women are 35% more likely to cite fear as a reason to not borrow compared to men. Periodic digital communication campaigns enable women to become better informed and may help overcome this fear. On-the-ground communication campaigns through influencers and opinion leaders are important to develop a loyal base of women customers who prefer, choose, and use digital credit.

Women are generally more cautious to adopt technology. Social proof is a key determinant of how low-income women adopt and use digital credit. Hence, incentives that align with peer recommendations can be an effective way for providers to reward women who help enroll other women.

3. A robust grievance resolution system with a human touch will help providers serve their women clients better

The current grievance resolution mechanisms (GRM) rely largely on the use of SMS, call-centers, and emails. These mechanisms are “low-touch4” in nature and mostly unused by the customers. Our research indicates the need for various levels of “touch” depending on the customer segment. Women customers who fear digital loans and are extra cautious prefer high-touch communication channels, particularly when they try out a new product or seek to resolve their grievances. Adding a proactive human face to the GRM to provide quick, hands-on solutions for issues faced by customers is essential to gain their trust and serve them better.

Studies have established the importance of digital credit to help households meet their expenses. However, due to negative shocks, the difference in its impact based on gender is not clearly established. While we lack hard data, the presence of anecdotal evidence is sufficient to get us started on further exploration and research. The business case is evident and providers should not hesitate, as the early movers will likely reap significant benefits.

Our report based on our study of the digital credit landscape in Kenya (2019), discusses the changes in the digital credit landscape. It highlights the core challenges, emerging concerns and also goes further to formulate recommendations for both regulators and suppliers to make the delivery of digital credit more responsible and customer-centric. Read it here.

[1] MSC analytics

[2] Supported by SPTF and Accion Smart Campaign

*Estimated based on population, target age group, mobile phone availability, number of digital loans per year and an average value of each loan

[3] MSC demand-side research and analytics

[4] Lower level of human involvement in the GRM process from the provider’s side

Is there room for optimism in the Kenyan digital credit sector?

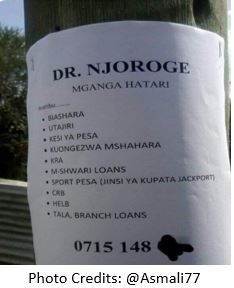

“Come and solve your problems related to M-Shwari, Branch, and Tala loans,” reads an advert from a local native doctor. These days, such adverts are a common sight across downtown Nairobi. While most Kenyans react to such “miracle cures” with disbelief, the prevalence of such posters is a reaction to the real struggle that Kenyan digital borrowers continue to face. A typical Kenyan digital borrower juggles three loans and struggles to repay on time, despite the fact that these are relatively small loans.

“Come and solve your problems related to M-Shwari, Branch, and Tala loans,” reads an advert from a local native doctor. These days, such adverts are a common sight across downtown Nairobi. While most Kenyans react to such “miracle cures” with disbelief, the prevalence of such posters is a reaction to the real struggle that Kenyan digital borrowers continue to face. A typical Kenyan digital borrower juggles three loans and struggles to repay on time, despite the fact that these are relatively small loans.

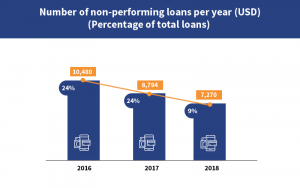

Among borrowers in Kenya, 2.2 million individuals have non-performing loans for digital loans taken between 2016 and 2018. About half (49%) of the digital borrowers with non-performing loans have outstanding balances of less than USD 10 . This narrative of over-indebtedness has also been a mainstay in the media, with a number of news articles highlighting disturbing trends and statistics from the sector.

This begs the question: Can we attribute any positive outcomes to the evolution of digital credit products and the growth of the sector in the past seven years? In a recently published study on the digital credit market in Kenya, MSC analyzed supply-side data from 2016 to 2018. The study findings indicate some positive and encouraging signs for the sector. In this blog, we look at these signs in detail.

[1] MSC analysis of supply-side data from 2016 to 2018

What is the good news?

1. Digital credit has broadened access to credit, particularly for those previously left out

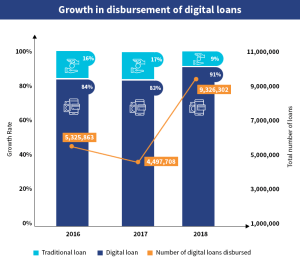

The digital credit sector has experienced significant growth. Our analysis shows that in the past three years, the number of digital loans disbursed has approximately doubled. In the same period, most of the loans (91%) were digital in nature. A key implication of this is also a broadening of financial inclusion in general. The latest FinAccess Household Survey is a testament to this, showing an increase in financial inclusion in the country from 75% in 2013 to 89% in 2019. This has largely received a boost from the ubiquitous nature of mobile financial services in the country.

2. The data reveals an improvement in loan quality

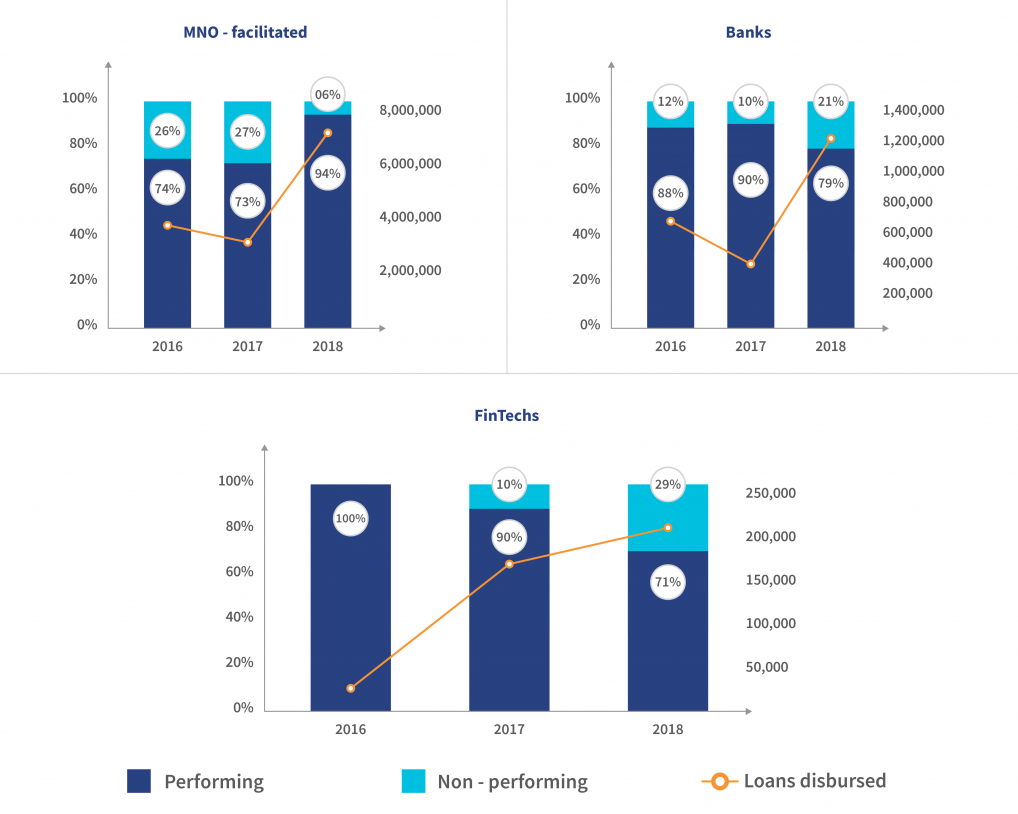

Almost a quarter of all digital loans issued in 2016 were non-performing. However, this figure had dropped to 9% for loans issued in 2018 by the end of that year , showing a 15% improvement in NPLs as a percentage of the total digital loans. In particular, MNO-facilitated lenders have managed to improve their loan quality compared to fintechs and banks. This is indeed remarkable.

Loan disbursements and book quality per provider

[2] This figure reflects loan performance as captured by supply-side data as of end-2018. It rose to 11.75% as of August, 2019.

Further analysis of disbursement and loan quality

All suppliers have generally increased their loan volumes from 2016 to 2018. With an increase in portfolio, we can expect an increase in NPLs. However, the key MNO-linked suppliers have managed to increase both quantity and quality of loans, as seen from the data in 2018.

We think that this is largely due to a number of reasons. First, these suppliers enjoyed a first-mover advantage, which has provided them with robust customer data—both from mobile money historical payment transactions and from a longer digital credit history to underpin their credit assessment. In particular, Safaricom has data of millions of loyal customers who use their wide range of services. Second, this first-mover advantage has also allowed time for continuous improvement of their algorithms for credit assessment. Safaricom has since started selling the credit scorecard for its customers to other providers in the market. However, it still enjoys the prerogative of deciding which suppliers can access this data.

What could be leading to better loan repayment?

Increased awareness of the consequences of loan default

In our qualitative interviews with 50 digital borrowers, we found that they are increasingly aware of the impact of defaulting digital loans. They know that they risk being negatively listed in the credit bureaus, which would lower their credit score and limit them from accessing formal credit. Further, most clients are willing to repay the loans mainly because of their innate nature or due to their need to retain and increase their loan limits and maintain access to the loan.

Improvement in credit scoring

Our engagement with the lenders revealed that their loan assessment algorithm has been getting better over time. The accuracy of credit scoring continues to improve with usage. The lenders have adopted a test-and-learn approach where they use the initial stages of the product to learn the financial behaviors of their customers, which include saving, borrowing, repayment, and defaulting. The inputs improve the accuracy of predictive analytics through machine learning. For example, M-Shwari piloted their product for 18 months. This allowed sufficient time to collect data that would support in predicting the performance of future borrowers.

Now that players in the industry have gained experience and showed positive trends, what would we like to see in the future?

• Improvement of the products offered to ensure that they are customer-centric: Nearly all the products from lenders have similar features. Their tenure is mostly one month and the monthly interest rate is around 7.5%. On the contrary, the needs of customers are diverse and thus require differentiated products. A handful of lenders have been focusing on the underserved segments. FarmDrive is an example of a fintech that lends to small-scale farmers with products that are designed specifically for the market segment. In addition, products like AfriKash, which focuses on informal women traders, offers flexibility in repayment that rewards those that repay early.

• Regulation of the sector: The regulatory architecture that governs digital credit requires a coordinated effort to be reformed. Largely, we may consider the sector to be regulated. This is because MNO-facilitated lenders and banks, which enjoy the biggest market share, are fully governed. However, fintechs remain largely under-regulated. They have recently formed their own association with 11 members, dubbed the Digital Lenders Association of Kenya (DLAK). The DLAK aims to strengthen the sector with best practices and consumer protection. The introduction of data-protection draft bills for legislation in July 2018 and the reform of credit data reporting templates are steps in the right direction. However, much more can be done.

Our report based on our study of the digital credit landscape in Kenya (2019), discusses the changes in the digital credit landscape. It highlights the core challenges, emerging concerns and also goes further to formulate recommendations for both regulators and suppliers to make the delivery of digital credit more responsible and customer-centric. Read it here.