Shumi and Sajia—two entrepreneurs of a similar profile but with very different stories

Shumi Akhter, 38, runs a dairy business in rural Munshiganj. About five years ago, she came across a YouTube video on dairy farming that caught her attention. She was so intrigued that she started researching online and reached out to her local markets to explore the potential of a dairy business in her area. She spoke to prospective customers, such as local sweetmeat shops and dairy cooperatives. Once she had finalized a few in-principle deals with them, she invested BDT 400,000 (USD 3,928) from the monthly remittances her husband sends from Singapore, where he works as an electrical mechanic. She started the business with three milch cows.

Sajia Akhter, 40, owns a beauty parlor in Dhaka, which she started around 12 years ago. Her motivation to start the business was to establish a source of income for her family, as her husband lacked secure employment or a well-established business. Her capital to start the business was around BDT 150,000 (USD 1,473), out of which she borrowed BDT 100,000 (USD 982) from her sister and used the remaining amount from her savings. She achieved limited success, but her business did not grow significantly, and she operates the finances and management of the enterprise on her own. Her only help is her daughter, who learned beauty skills from her mother and assisted her during work hours. Sajia does not have big ambitions for the business—she wants to be able to repay her loans and have enough money left to run the parlor.

Shumi and Sajia are among the ~600,000 women-run cottage or micro, small, and medium enterprises (CMSMEs) in Bangladesh. Sajia’s story represents the perils of women-run businesses, and Shumi’s story is a beacon of hope. But what is the real problem? What is holding up a seasoned entrepreneur like Sajia, and what enabled Shumi to grow her business so fast? The most commonly prescribed “silver bullets” are access to finance and skills development. But we must understand other essential factors affecting WMSEs to understand the whole picture.

A 360-degree view of the women business owners’ lives

Little evidence is available on how women-owned businesses are run. The impact of social norms restricting women’s agency is also unclear. Hypotheses, such as men making business decisions for WMSEs and women preferring different types of businesses compared to men, are emerging only now due to research on microenterprises. In this context, coupled with the motivation to reduce access to finance barriers for women entrepreneurs, MSC has started a Women business diaries-based action research in Bangladesh, with support from the Gates Foundation. We will track all financial and nonfinancial transactions of ~500 women entrepreneurs.

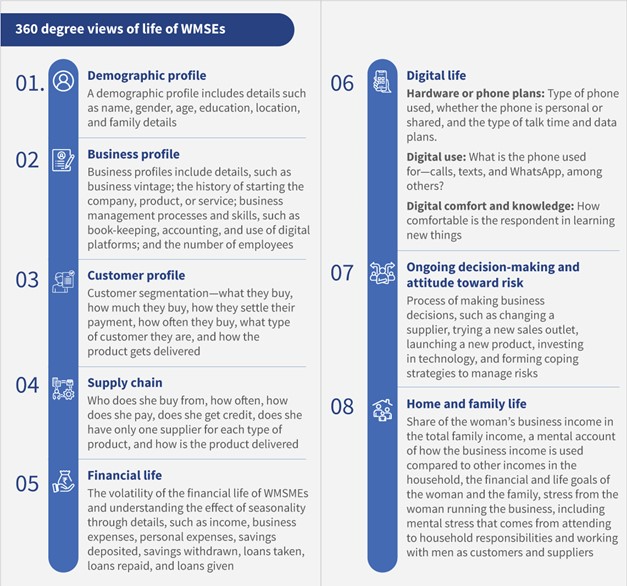

MSC will take a comprehensive view of the lives of women business owners, including their financial life, business management, digital life, and personal life. Figure 1 summarizes the different dimensions of women entrepreneurs’ life that we will capture in this research. We will collaborate with financial institutions to use insights from this action research to develop gender-centric financial products to help WMSEs in Bangladesh.

We have a variety of women-run businesses in our sample, including apparel businesses, grocery shops, eateries, artisans, tailors, beauty parlor owners, and agriculture and livestock-related businesses. We use MSC’s DatIn app to track these WMSEs’ daily financial transactions, such as income, expenses, savings, and credit. Further, we use digital technologies to analyze the collected data. We also conduct regular in-depth interviews and IVR-based surveys to understand the reasons behind their financial decisions and different aspects of their lives.

What is in store?

We have completed profiling the diarists, and the diarists have started to record their daily financial transactions. Over time, a fuller picture of the lives of WMSEs will emerge as the data starts pouring in. We will share the insights through a series of knowledge pieces called “The big smalls of Bangladesh—Insights on women-owned enterprises in Bangladesh.” The different editions of this series will provide insights into the lives of women entrepreneurs. These insights will further help start a conversation on the need for a contextualized multidimensional strategy to help WMSEs.

Watch this space as we dive deeper into the lives of these WMSEs.

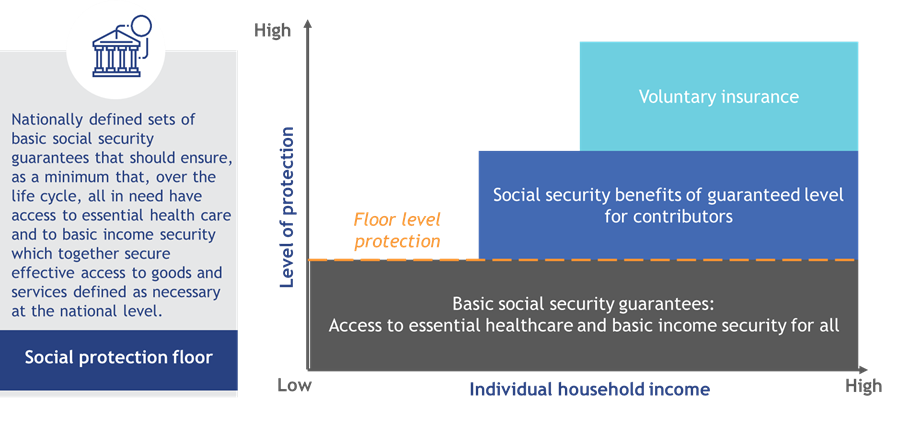

National social safety nets should consider women’s lifetime loss of earnings due to their role as primary caregivers and accordingly design differentiated gender-equitable social security programs.

National social safety nets should consider women’s lifetime loss of earnings due to their role as primary caregivers and accordingly design differentiated gender-equitable social security programs.