In recent years, India has moved to a leading position in digital payments and developed an ecosystem that enables the uptake and usage of digital payments. Many countries now seek to replicate India’s payments systems, particularly the Unified Payments Interface (UPI). This blog highlights the evolution of India’s payments landscape and looks into issues and ideas that contributed to this evolution. It briefly discusses the controversial waiver of the merchant discount rate (MDR) to increase the number of use cases in the person-to-merchant (P2M) category.

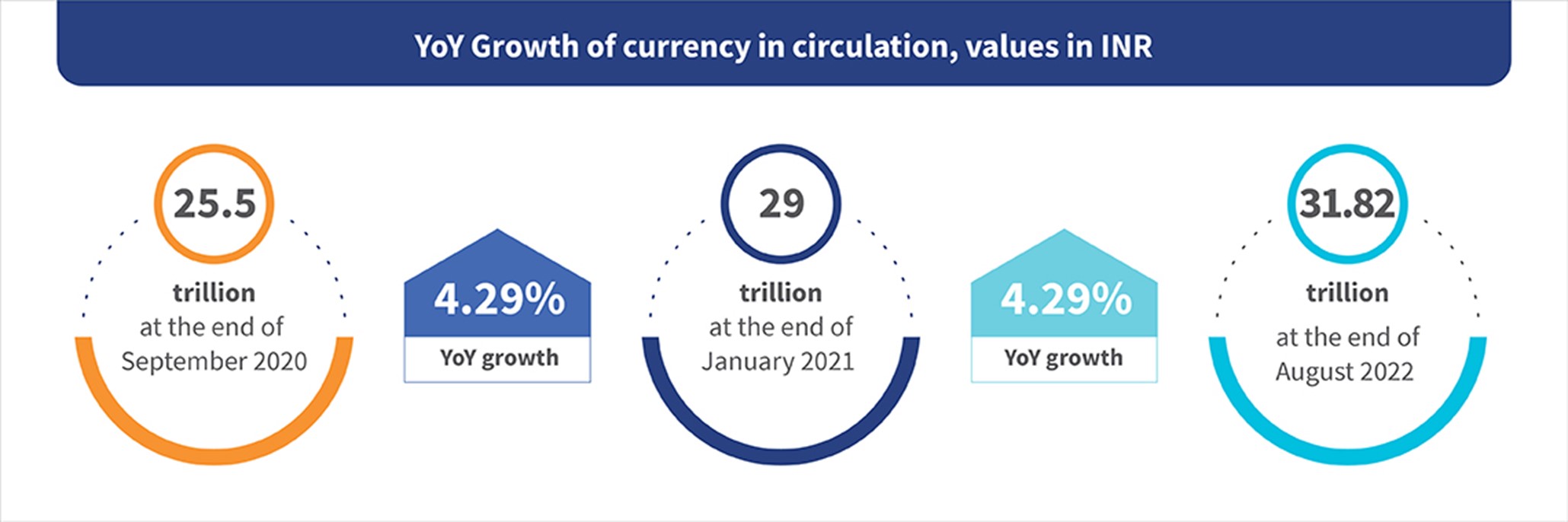

Digital payments in India have grown rapidly. Transactions increased from 23.4 billion in 2019 to 46.7 billion in July 2022, aided by several digital payment products, such as UPI and Aadhaar-enabled Payment Systems (AePS). The number of first-time digital payment users increased with these payments products, coupled with growing apprehensions about handling cash during the COVID-19 pandemic. Improvements in payments infrastructure, disruptions in information and communications technology, a responsive regulatory framework, a conducive policy environment, and a greater focus on customer-centricity have transformed India’s payments ecosystem.

Market offering or share of leading players—evolution over time

The major digital payment products available in India are Aadhaar-based payments such as Aadhaar Enabled Payments System (AePS) and BHIM Aadhaar Pay (BAP), contactless payments such as Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and Bharat Bill Payments System (BBPS), and card-based payments such as RuPay and debit card:

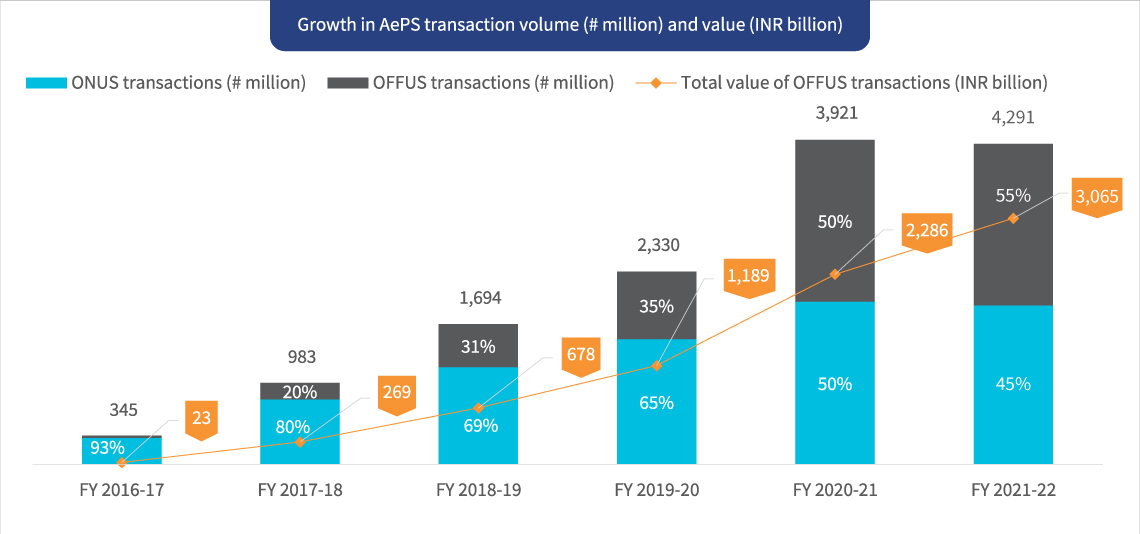

- AePS transactions increased by 290 million from 113.8 million in 2018 to 404.45 million as of July 2022 as people withdrew more money, thanks to increased domestic remittances and governments’ emergency cash transfer programs. AePS has boosted DBT payments in rural geographies with 407 million average monthly transactions. More DBT payments have led to the inclusion of users who do not own smartphones and need assisted services.

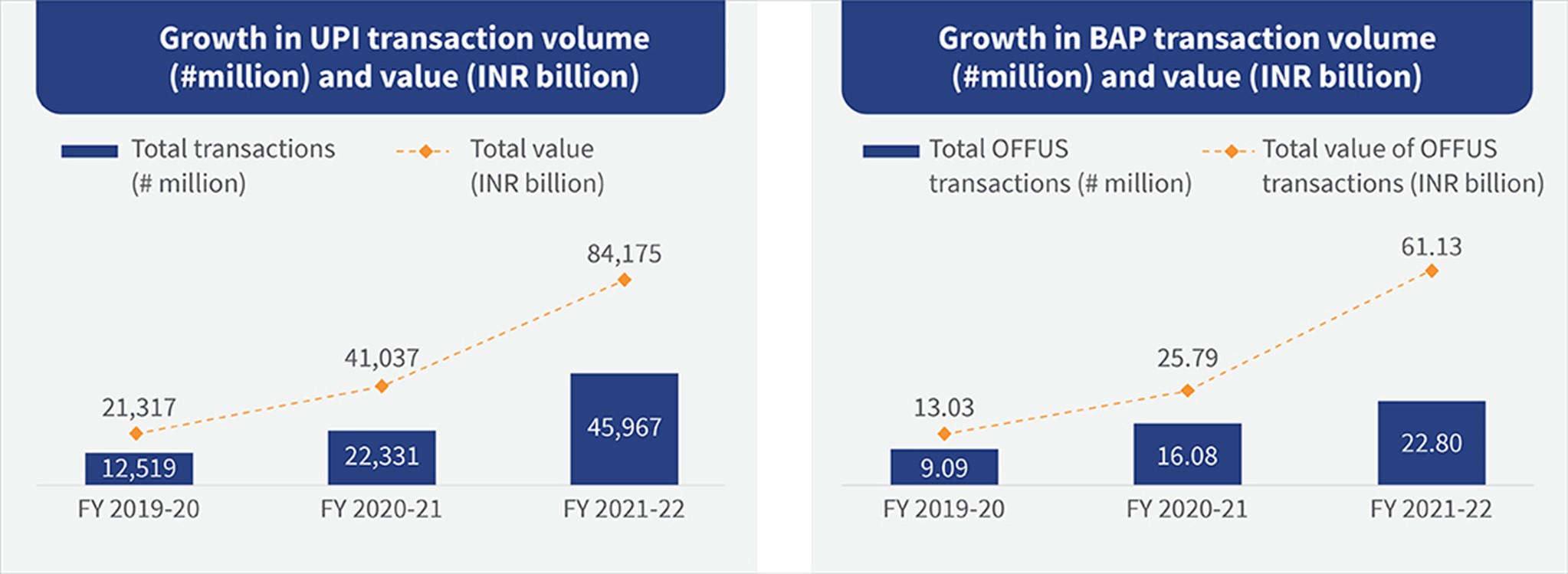

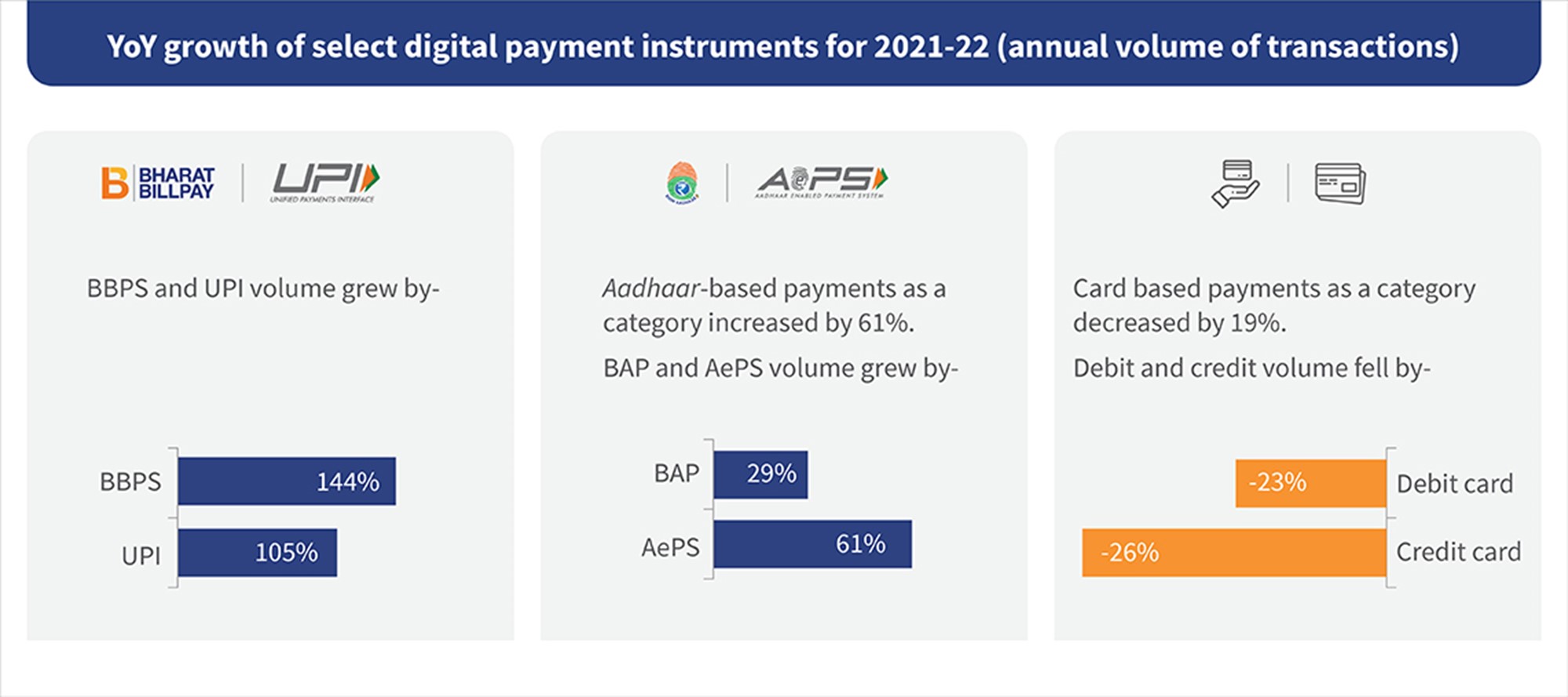

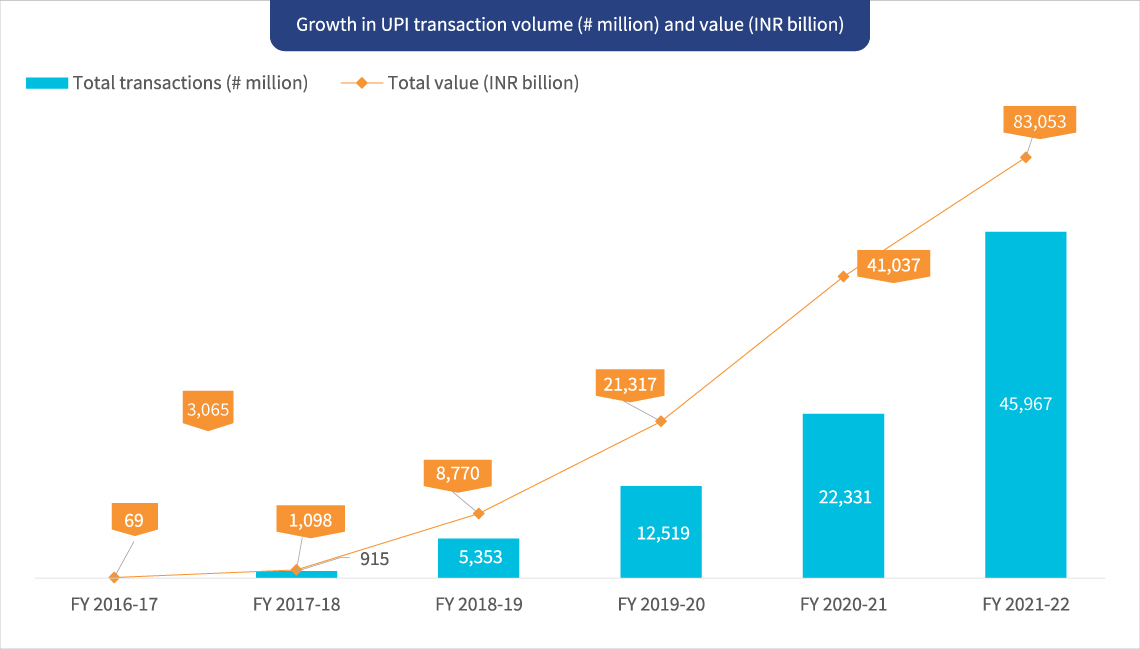

- UPI transactions grew at a CAGR of 119% and 138% by volume and value in the past five years, from FY 2017-18 to FY 2021-22. Today, UPI drives India’s digital payments with 300 million active users and 57 billion average monthly transactions. UPI offered one of the safest payment modes for person-to-person (P2P) and P2M transfers and outstripped all other payment platforms during the pandemic. In 2022, NPCI launched UPI123Pay, allowing feature phone users to use the UPI platform via Interactive Voice Response (IVR). UPI123Pay’s launch points toward the further adoption of digital transactions in the countryside, where most citizens still do not own smartphones.

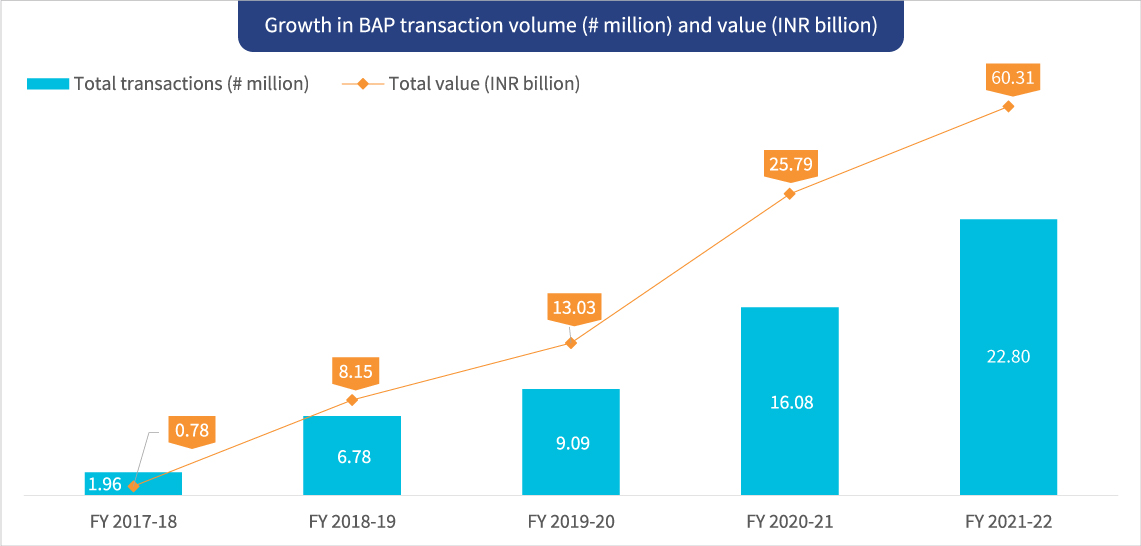

- BHIM Aadhaar Pay (BAP) is the merchant version of AePS. Unlike UPI, it enables merchants to receive digital payments from customers through Aadhaar authentication, whereas UPI requires customers to have a smartphone, UPI ID, and PIN. The transaction volume for BAP increased by 91% in the past five years. The average transaction value has risen steadily from INR 398 (~USD 5.38) in FY 2017-18 to INR 3,189 (~USD 39.92) in FY 2022-22, which indicates people are increasingly using BAP for large ticket-size transactions. The push from the acquiring banks and the cashback rewards available on transactions till December 2019, drove merchants and consumers to adopt BAP widely across semi-urban and rural India.

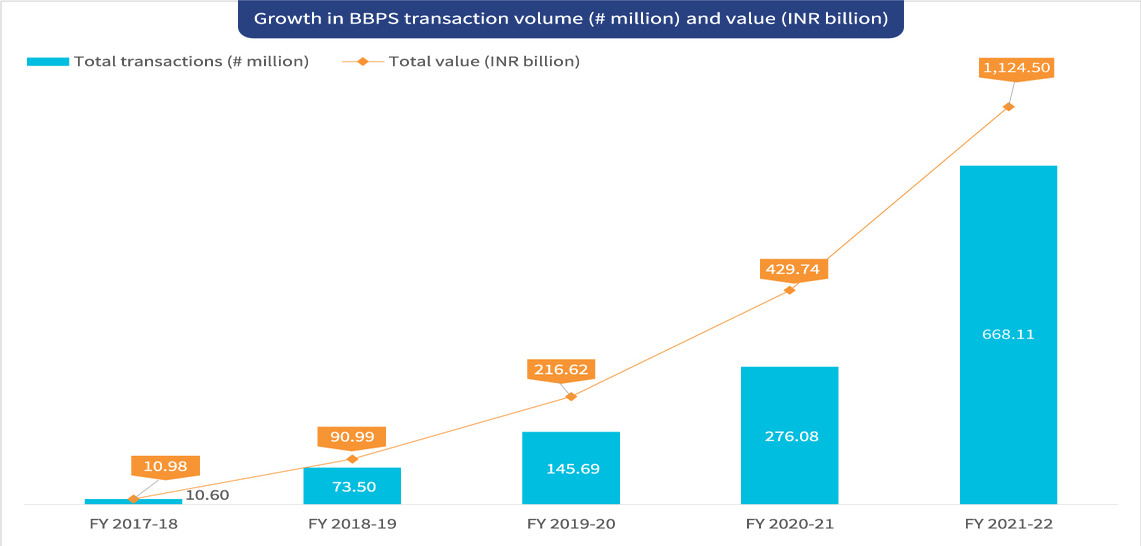

- Bharat Bill Pay System (BBPS) has consolidated India’s recurring bill payments industry under one payment system. It provides the convenience of round-the-clock bill payments to multiple billers from a single platform. Transaction volumes have grown significantly by 62% over the past five years, which indicates more customers now prefer BBPS for bill payments. By integrating recurring payments, BBPS has added 19,500 unique billers across 19 additional categories besides utility bills and airtime top-ups, such as education fees, loan repayments, insurance, fees for cooking gas, municipality taxes, and subscription fees.

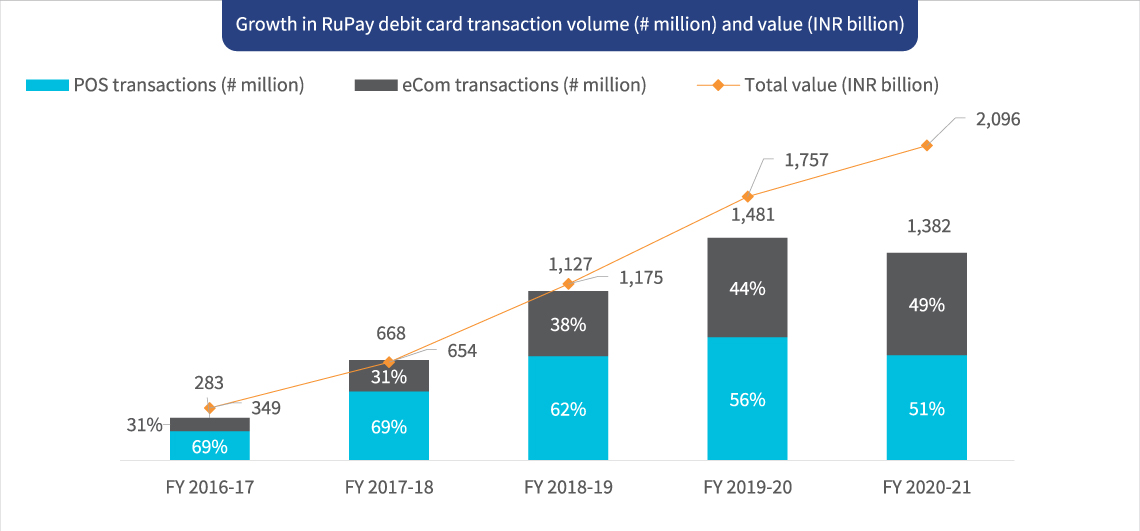

- RuPay is a homegrown card payment network. It offers low processing fees and wide acceptance at ATMs, PoS devices, and e-commerce across India. RuPay’s market share in total debit cards issued increased from 17% in 2017 to 60% in 2020. More than 1,224 banks have issued 94 billion RuPay debit cards. Transaction volume grew by 388% over the past five years. Both offline and online merchant payments remain significant use cases for consumers.

30% cap (of total volume) imposed by NPCI

The NPCI declared a 30% market cap on the total volume of UPI transactions for all third-party app providers (TPAPs) on 5th November 2020. The cap is calculated on a rolling basis per the total volume of UPI transactions during the preceding three months, starting on 1st January 2021. NPCI will inform all TPAPs over email once their total UPI transaction volume reaches 25% to 27%. Players will receive a second alert upon crossing the threshold of 27%.

Once players cross the threshold of 30%, they must stop onboarding new customers immediately. PhonePe, Paytm, and Google Pay continue to dominate the UPI market. They collectively hold 94.8% of the total UPI transactional volumes and 93% of the total value as of March 2022. This new policy on market cap was formulated and implemented to ensure that the UPI infrastructure offers a positive customer experience and discourages a handful of players from monopolizing the digital payments landscape.

QR code-based payments

India has approximately 750 million smartphone users, which is projected to reach 1 billion by 2026. The increasing affordability of smartphones, growth in the number of users in rural India, and government initiatives have grown India’s smartphone user base in recent years. Rural India has propelled this rise in smartphone use with a projected CAGR of 6% from 2021 to 2026. QR code-based payments can potentially create significant growth in digital payments, especially among customer segments with low financial literacy across India. With low infrastructure requirements, two-way transaction flows, secure transactions, and overall simplicity, QR codes offer an easy on-ramp to digital payments.

The COVID-19 pandemic aided the acceptability and uptake of QR code-based payments mainly due to their contactless nature, quick turnaround time, and ease of usage. So far, QR codes offer multiple use cases in both P2P and P2M transactions. Examples include toll tax payments, payments at grocery stores, mobile app downloads, and utility bills. They present a broader opportunity to increase use cases to allow more customers to pay using QR codes across various platforms.

Moreover, the regulatory environment in India is focused on open banking and making all QR code-supporting platforms interoperable. This interoperability enables customers to make payments across different FSPs, wallet players, and other platforms.

MDR

Policy initiatives, such as the waiver of MDR charges for providing financial incentives to promote digital payments, show the government’s intent to further financial inclusion through digital pathways. This initiative was expected to make onboarding merchants easier for businesses and influence more customers to adopt digital payments. However, the zero MDR policy hurt the payments ecosystem as it threatened the survival of several payment gateway entities, hampered innovation efforts, and slowed down India’s expansion of the digital payments infrastructure. This is demonstrated by RuPay’s performance, even though it commands 60% of the Indian debit card market, its monthly average transaction volume was less than 50% as against other debit cards in FY 2021.

Banks now hesitate to invest in improving their technology stack to smoothen the flow of digital payments due to the lack of incentives. The MDR may discourage players in the payments ecosystem from promoting digital payments. Therefore, some reimbursement or reconsideration may be needed to prevent this.

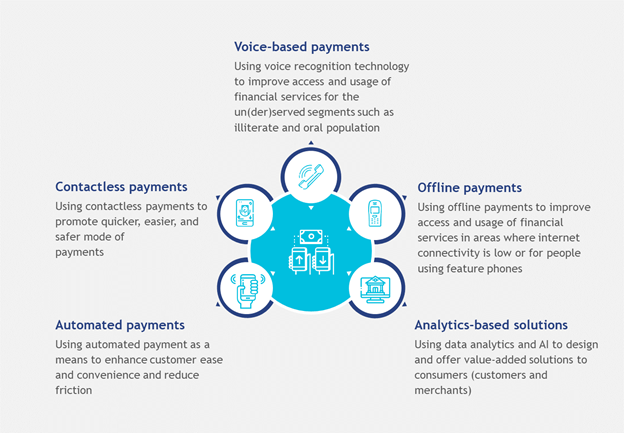

Future opportunities

India’s payments ecosystem is in good health. With the boost that COVID-19 provided, it is poised for further growth. The following blog in this series examines the future and opportunities to further turbo-charge the growth of digital payments in the country.

Awareness:

Awareness: