The economic disruptions from COVID-19 have left MSMEs in Kenya struggling to survive. Our report highlights the impact of the pandemic on the business operations, supply chains, as well as the household income and expenditure of MSMEs. It delves deeper into the coping strategies these enterprises adopted to mitigate the effects of this disruption. The report also provides policy recommendations to boost the income of MSMEs, reduce their burden of expenses, and help them recover once the crisis is over.

Blog

COVID-19: A harbinger of consumer behavior shifts among FinTech users

“Decades of progress on reducing poverty and increasing financial inclusion—all of that is at risk.”

– Michael Schlein, Accion

38% of small startups have already run out of cash in India with more predicted to fall prey to the impact of the pandemic. If this seems ominous, FinTech entrepreneurs should brace for what is likely to redefine the principles of business in India as tailwinds of COVID-19 change consumer behavior. Can FinTechs do anything to manage this shift? The answer, as usual, lies in the power of collective and intelligent use of data.

Shock and awe: Immediate effects of consumer behavior for FinTechs

Based on discussions with a slew of FinTechs, investors, and industry associations, we identified significant impacts on both the lending and saving segments over the past few weeks.

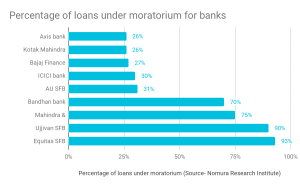

No rest for the lenders: The lockdown came into effect on 24th March 2020 in India, which led to disruptions in supply and a fall in consumption. With consumers opting to spend less on discretionary items and MSMEs reeling under the adverse impact on consumer and supply-chain mobility, banks and digital lenders have pulled back on lending to MSMEs by as much as 5.4%. Even retail credit FinTechs were not immune to the effects of the pandemic. These FinTechs, primarily focus on the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segment, bore the brunt of the lockdown. Around 85% of migrant workers have not earned anything since March 24th while the unemployment rate climbed as high as 23.52%. Not surprisingly, a significant number of existing borrowers opted for a three-month moratorium on loans offered by the Reserve Bank of India, which has now been extended until 31st August 2020. Traditional banks witnessed a sharp rise in delayed repayments. The chart given above highlights a worrying trend where the increase in loans under moratorium is commensurate to the riskiness of the banks’ borrowers, with small finance banks having the highest amount of loans under moratorium.

No rest for the lenders: The lockdown came into effect on 24th March 2020 in India, which led to disruptions in supply and a fall in consumption. With consumers opting to spend less on discretionary items and MSMEs reeling under the adverse impact on consumer and supply-chain mobility, banks and digital lenders have pulled back on lending to MSMEs by as much as 5.4%. Even retail credit FinTechs were not immune to the effects of the pandemic. These FinTechs, primarily focus on the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segment, bore the brunt of the lockdown. Around 85% of migrant workers have not earned anything since March 24th while the unemployment rate climbed as high as 23.52%. Not surprisingly, a significant number of existing borrowers opted for a three-month moratorium on loans offered by the Reserve Bank of India, which has now been extended until 31st August 2020. Traditional banks witnessed a sharp rise in delayed repayments. The chart given above highlights a worrying trend where the increase in loans under moratorium is commensurate to the riskiness of the banks’ borrowers, with small finance banks having the highest amount of loans under moratorium.

We can extrapolate these percentages to digital lenders who generally lend to even riskier borrowers. To add to the misery, digital lending NBFCs are now crippled with a liquidity crunch as banks have not extended the moratorium to them. This proved to be a double whammy for digital lenders, whose repayments have dried up while at the same time, they are forced to repay their loans. A co-founder of a large digital lender quips, “60% of our customers have opted for a moratorium while only around 40% of our lenders have offered us moratorium. The situation is likely to be far worse in smaller FinTechs.”

Fear and shirking in savings: Saving FinTechs or “WealthTechs” in India mostly offer returns higher than banks through market-linked products tailored to an individual’s assessed risk profile. For instance, they may offer ~6% interest in a liquid fund as compared to 4% in a savings bank account. Such demand rides on bullish markets and increasing disposable income. While the Indian stock market saw its worst single-day loss on 23rd March, 2020 as NIFTY50 fell by 12.98%, unemployment and pay cuts continued to drag down disposable income. April saw a 28% month on month (MoM) drop in the number of employed people, with around 27 million youth losing their jobs. Sure enough, the market meltdown and loss of employment resulted in mass redemptions with the mutual fund industry reporting USD 27.6 billion in net outflow. Uncertainty on the COVID-19 vaccine, opening up of the economy, and a volatile market collectively influenced consumers to hoard cash, which is perceived to be a safe haven. WealthTechs, which mostly earn revenue from trail-fee commissions as a percentage of their assets under management (AUM), have been left reeling in the wake of these redemptions and drying up of new investments.

Is there a risk of a deeper malaise?

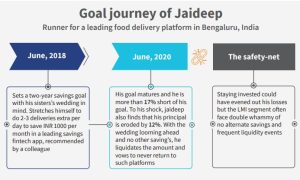

Savings FinTechs, supported by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and bodies such as the Association of Mutual Funds in India (AMFI), have put in more than a decade’s worth of effort to educate the upper-LMI segment on the benefits of capital market investments. The pandemic-induced market meltdown is likely to cut deep into the trust of the “new-to-investments” category. This segment is alien and averse to the idea of principal erosion. The infographic below explores what this means for Jaideep, who has worked as a runner for a leading food-delivery app since 2018.

Unlike savvy investors, most of the LMI segment experience frequent requirements of liquidity. This results in premature withdrawals and hence a realization of losses. For example, in case of a medical emergency, a migrant cab driver in Mumbai is likely to liquidate his investments while his current cash inflows go towards meeting the repayments for his car loan. Without any regard to the present value of his investments, the driver is susceptible to compromising his long-term plans. The wealthy, however, can afford to stay invested and time their exit when returns are at near peak. The current crisis could potentially decimate the newfound trust of people like Jaideep or our hypothetical cab driver in digital savings platforms and keep them out for years to come, thus setting us back by a decade.

Digital lenders, on the other hand, are battling with changes in the repayment behavior of borrowers. Information asymmetry and deteriorating repayment discipline in the face of the announced moratorium are the driving factors behind this shift. Confused borrowers in hinterlands regard the moratorium either as a waiver or repayment holiday with no interest accrual. The ill-effects of farm-loan waivers on the credit culture of farmers are well documented and it is only a matter of time before the credit culture of digital credit borrowers suffers the same fate. Overall, the moratorium could result in an alarming increase in NPAs once it is lifted. We may also see a fall in repayment discipline for new loans, forcing lenders to either increase the interest rates of loans or shy away from the LMI segment altogether.

What can the FinTechs do today?

FinTechs must take advantage of this shift in consumer behavior with the help of the most potent weapons in their arsenal—data and technology. They can use the following four-point actionable tactic in the fight against the effects of this pandemic:

- Digital lenders should approach customer segments differently: Depending on whether they lend to the elite and the affluent or the LMI segments, digital lenders can choose an opt-out or opt-in strategy to provide moratoriums. The lender can make the moratorium applicable on all loans by default, unless the borrowers explicitly opt-out or vice-versa. An opt-out strategy for the LMI segment has two core benefits:

- The LMI section is the most severely affected. An opt-out strategy puts borrowers under moratorium by default without requiring any action. This can help the households improve their long-term financial health and establish the lender’s brand as a preferred source of credit for future needs. However, this would require clear, consistent communication to ensure that borrowers are aware of default and its consequences.

- A double whammy of income loss and information asymmetry within the LMI segment means that borrowers are unlikely to take any action on their own. Hence, unless they explicitly opt-out, cash-strapped borrowers will be under the moratorium, which can save lenders from potential mass NPAs.

- Transparency is an ally for digital lenders: Digital lenders should use high-engagement channels, such as WhatsApp to inform borrowers about the interest accrued if any. They should follow it up with reminder countdowns that lead up to the end of the moratorium. This prevents potential shocks for the borrowers and helps them mentally account for an extended repayment schedule.

- Tailoring to stimuli: Saving FinTechs should triangulate consumer data points and identify consumers with fragile financial health. The FinTechs can then educate these consumers proactively and offer them overnight and money-market mutual funds. On the other hand, consumers from the savvier section with a significant wallet share should be educated on the adoption of an averaging strategy in bearish equity markets.

- A nudge-based approach: Taking a leaf out of Nobel laureate Richard Thaler’s book, FinTechs with goal-based savings should tap into behavioral economics. A few strategies for them could be as follows:

- Loss aversion– FinTechs should quantify and display the potential loss if users withdraw now. FinTechs should also consider displaying the loss-amount as a label of the “withdraw button” in the app; and

- Nudges- FinTechs should map the call to actions on their apps through a choice architecture to nudge the users to the right actions. This would essentially involve layering actionable buttons with decision points that arrest inertia and force the user to stop and evaluate options. A few examples could include moving the “withdraw button” to secondary screens in the app so that users do not see it as a prominent call to action button or route the users through alert windows before committing to withdraw funds. FinTechs should place positive reinforcement texts on primary screen buttons that encourage to value-invest during bearish markets.

While the former should accentuate loss of utility and dissuade the user from liquidating; the latter should encourage the users to stay invested if not invest more funds.

The ecosystem can survive the current pandemic and come out stronger only if all FinTechs engage in cross-company dialogue and share best practices and pitfalls. Investors and accelerators also play a tremendously important role in the dissemination of best practices that go beyond portfolio companies. The potential adverse effects of any shift in consumer behavior are likely to have a whiplash effect as they move through the layers of digital financial services unless the industry collectively moves to arrest them today.

Through holistic research on FinTechs and their ecosystem partners across multiple geographies, MSC will continue to track and assess policy, regulatory, and industry responses, review the investment climate, and determine the coping strategies of FinTechs.

Our objective is to design programmatic interventions to support FinTechs, especially the ones focused on LMI segments, to survive, rebuild, sustain, and grow. We will continue to equip regulators, policymakers, ecosystem partners, and investors with our findings to empower these FinTechs to function effectively and play a positive role during the pandemic.

Stay tuned for more updates on www.microsave.net.

This blog is a part of a COVID-19 research study conducted in the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The lab receives support from some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

The FI lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC.

Indian agriculture during and after the pandemic

Impact of COVID-19 on agriculture

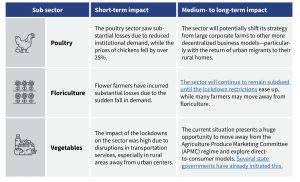

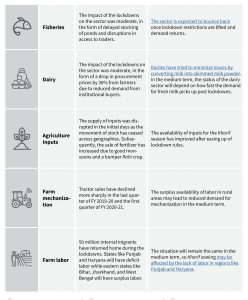

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, agricultural activities related to production and marketing have been deemed “essential services” and were not restricted in any state. However, the lockdowns shut the operations of retail sellers and restricted their movement, constrained the movement of goods severely, closed processing units that consume agricultural commodities, and—despite their essential service tag—shut down some mandis and markets. As the country begins to open up again, we summarize the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the different sub-sectors and look at the ones that are in a position to bounce back and the ones that will continue to struggle.

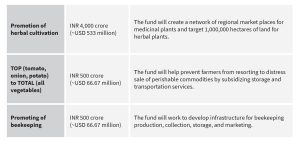

The Government of India (GoI) and many state governments have designed several measures to address the problems that farmers face. The GoI has announced the following measures[1]

The GOI has also taken a few important policy decisions, including:

- Amendments to the Essential Commodities Act to deregulate the stock limits and prices of commodities like cereals, edible oils, pulses, onions, and potato to allow farmers to realize better prices

- Agriculture marketing reforms to remove restrictions and allow farmers to sell to any buyer of their choice in any geography, including through electronic market platforms—thereby diluting the monopoly of the APMCs

However, the payments under the PM Kisan Yojana alone, which reaches about 85 million farmers out of a potential beneficiary base of 140 million, is likely to provide immediate relief and food security. All other measures will only reach or have an impact on the farmers in the medium to long term. One new measure is the INR 1-lakh-crore fund (~USD 13.3 billion) for agricultural infrastructure. The response from the government shows that it is sensitive to the problems in the farm sector but has been unable to define the nature of the complex challenges precisely. It has therefore adopted an approach akin to “a rising tide will lift all boats” in its measures. However, not all vulnerable farmer households have “boats”.

Three key issues that have emerged in the post-COVID-19 era

Agriculture finance

Finance for agriculture from formal financial institutions has been growing steadily year on year for the past 15 years. The ratio of agri-credit outstanding to agri-GDP increased from 13.34% in 2003 to 51.56% in 2017-18. This was largely due to efforts like the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) program.[2] By the end of March, 2020, the outstanding agricultural credit was INR 11.69 lakh crores (~USD 155.9 billion). However, this seemingly large sum constitutes only 12.5% of the gross bank credit in India. The share of bank credit for agriculture continues to remain less than agriculture’s share in the GDP (16.5%). According to the financial inclusion survey carried out in 2015-16 by NABARD (NAFIS), 38% of the farm households surveyed depended on non-formal sources of finance, with 30% relying exclusively on informal sources. Unsurprisingly, small and marginal farms depended more on informal sources of finance.

One of the problems that have emerged recently is credit for the Kharif season. With more than 30 million farmers who have received a moratorium on loans until August, 2020, the prospects for securing Kharif crop loans do not look bright. Banks rarely provide a second loan when an earlier one is outstanding. Once the lockdowns lift, banks will busy recovering loans that come out of moratorium and processing new proposals under the different packages—the loans for Kharif season are unlikely to get priority.

The merger of a large number of public sector banks coupled with the uncertainties regarding staff placements in the branches will add to the problems of a significant number of farmer customers. Stakeholders need to find solutions to these problems and develop simple systems to provide Kharif loans. For example, in Maharashtra, the state government has provided a guarantee[3] for the repayment of outstanding loans of farmers, paving the way for the disbursement of new Kharif loans. Similar initiatives are required in other states to increase and simplify the flow of credit.

Women in agriculture

The Government of India in the Economic Survey (2017-2018) stated that the agricultural sector in India is undergoing feminization. Even though women only own 12% of the total agricultural land, over 73% of rural women workers have found employment in agriculture.[4] In the face of shrinking employment opportunities in agriculture, men have diversified into the rural non-farm sector, while male out-migration has emerged as a major livelihood strategy.

The World Bank estimates that India has more than 140 million internal migrants.[5] With fewer non-farm sector jobs available and reverse migration of men back to villages, more men will be available to take up agriculture. An estimated 50 million inter-state migrant laborers have returned to their villages from cities after the nationwide lockdown. This could affect women’s standing as farmers and risk reversing the gains achieved over the past decade.

With men back in the villages, women may be pushed to undertake the least paid and most menial agricultural tasks. Their wage rates may dip further. As men are now locally present, they may get more involved in the marketing of their produce and thus control the money. Women’s self-help group (SHG) networks and NGOs will have to play a larger role in negotiating space for women. Anecdotal evidence continues to suggest that SHG members have been supporting each other by exchanging labor on the lines of Pragathi Bandhu groups promoted by Shree Krishan Dharmastala Rural Development Project (SKDRDP)[6].

SHG federations and village organizations could also play a larger role in arranging for the supply of inputs and ensure aggregation and marketing of produce. The women FPOs promoted by State Rural Livelihood Missions (SRLMs), such as JEEViKA in Bihar, have also been leading the way in developing farm-to-fork models for women farmers to market commodities. Civil society organizations and governments should organize suitable capacity-building activities to help women retain their space. Work allocation under NREGS should also give adequate representation to women.

Farmers’ Producer Organizations (FPOs)

The dilution of APMC and the ECA opens up exciting market opportunities for FPOs. If all states align their policies with the central government’s ordinance, then this can unshackle the buyers and allow them to purchase from anywhere—which in turn means more choice for farmers. Several large corporates, such as Godrej and ITC have also shown an increasing preference to trade with farmer collectives than the traders on whom they have traditionally had to rely on. The bargaining power of farmers or FPOs will increase as they are not required to sell within a specific geography.

The recent focus on setting up 10,000 FPOs is well-intentioned. How FPOs have responded during the pandemic and lockdown has been a revelation for farmer members as well as for other stakeholders. However, many dormant FPOs exist in the system and the investments made in their formation remain idle. As a first step, it would be useful to examine the operations of the 7,300+ registered FPOs and design interventions and assistance to help dormant and sub-optimal ones realize their full potential.

The increased confidence of corporates in FPOs has enhanced the scope for contract farming and improved corporate tie-ups. However, to ensure that all parties uphold contract terms, it is necessary to frame contracts to incorporate insurance-based safety-net provisions, as well as provisions that allow farmers to share any unexpected gains due to market buoyancy. It is equally important to set-up dispute resolution mechanisms in the form of arbitration bodies at the district or sub-district levels, which are easy and cost-effective for both farmers and contracting entities.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis has bought to the fore some of the persistent problems that Indian agriculture faces. Despite the impressive strides made toward improved access to institutional credit, dependency on informal credit sources remains high, especially among smallholder farmers. The government has to step in to ensure farmers can access fresh credit for the Kharif season. The other important dynamic that policymakers and the wider development community need to look at is preserving the role of women in agriculture. The surplus labor in rural areas can potentially undermine the status of women in agriculture, and push them further into economic exclusion.

The SHG movement that includes SHG federations and women-owned FPOs should be utilized to improve market price realization for women farmers and improve the engagement of women in value-addition activities such as low value processing. The push for market reforms has put the focus on the transformative role of FPOs in agriculture marketing. The dilution of the ECA and APMCs provides a huge opportunity for FPOs to link directly with buyers across the country and also to develop more direct-to-consumer supply chains, and in the process, improve their incomes.

[1] USFDA: COVID-19 in India – GOI’s Economic Package for Self-Reliant India – Food and Agriculture Items

[2] RBI: Report of the internal working group on agriculture credit (2019)

[3] The government has given clear directions to banks to note pending loans as “to be paid by the government” and to not consider farmers as defaulters.

[4] https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1518099

[5] World Bank. 2020. COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens. Migration and Development Brief No. 32;. World Bank, Washington, DC. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33634 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.”

[6] Developed by SKDRDP, “Pragathi Bandhus” are unique models of male-member self-help groups that center around the cultivation of waste and fallow lands through labor sharing. Such groups organize and empower small and marginal farmers and laborers through the transfer of governance to the village level.

Liquidity support for G2P agents in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic

These challenges, coupled with the overall movement restrictions imposed by the government to curb the spread of COVID-19, have severely affected the business of these agents. They need more support than ever to manage liquidity and hence remain operational. Our blog highlights some measures that policymakers and service providers in Indonesia may consider to support the agents in these difficult times.

COVID-19 management by local governments: Is there a mantra to follow?

COVID-19 is yet to reach India’s 112 aspirational districts[1] in full force. The disease appears to be spreading first and most widely in concentrated urban areas. It is not surprising, therefore, that these largely rural districts have seen only 2% (610 cases in total as of early May, 2020) of cases so far, despite lower social development indicators. Yet that does not mean that these areas, home to more than 20% of the country’s population, have not been affected deeply by the global pandemic.

It is not hard to imagine the potentially devastating consequences of a pandemic of this nature for people who live in rural areas. Multiple aspects of economic and social vulnerability characterize their daily lives. To mitigate the repercussions of the pandemic, Aspirational Districts have been pioneering simple yet effective measures to solve the immediate needs of the community during the pandemic, which other districts across the country can use at scale.

So, how can aspirational districts mitigate the consequences of the pandemic while continuing to prepare a response to the potential arrival of more COVID-19 infections—or the future arrival of another pandemic? In our search for answers, we look at the approach taken in the Goalpara district in Assam. Goalpara is picturesque, located a few hours away from the state capital at Guwahati. The West and East Garo Hills districts of Meghalaya surround Goalpara on the south, while the mighty Brahmaputra River runs along the north. The following section identifies some of the bottom-up measures rolled out there thus far and looks at policies centered on engaging with the community, embracing digital channels, and solving immediate needs.

Engaging with the community

Goalpara has been quick to involve civil society, businesses, and the public in its COVID response. The district has organized community members to engage with vulnerable groups, mobilize the production of needed goods, and support the medical community.

Efforts include the launch of “Mission Goalpara Cares,” which has tasked teams of teachers and college students to call elderly residents regularly, inquiring after their physical and mental well-being, and determining if they need assistance from the government. The district has also deployed Nehru Yuva Kendra and Civil Defense volunteers to help manage the disbursement of direct benefit transfers under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana at potentially crowded locations, such as banks and customer service points by maintaining social distancing measures.

Protective equipment, from sanitizer to masks, foot covers, and head covers have been put into production through the work of nearly 150 women who form part of self-help groups under the Assam State Rural/Urban Livelihood

Mission network. The Goalpara district administration expects to procure some 162,000 masks from these collectives in the coming times, which it will then sell or distribute to the police, administrative personnel, and the public to bolster public health measures and local livelihoods.

Mission network. The Goalpara district administration expects to procure some 162,000 masks from these collectives in the coming times, which it will then sell or distribute to the police, administrative personnel, and the public to bolster public health measures and local livelihoods.

Local retailers have been on-boarded to provide new home delivery services for essential goods. The District has also ensured that frontline medical workers receive hotel accommodation, free Wi-Fi service, and personalized “care kits” during their duty period. These medical professionals are involved in the treatment of patients and have been working away from their families. These measures have kept the morale of the medical workforce high during this stressful time. The district administration also ensured life insurance coverage of ASHAs, ANMs, GNMs, and cleaners in the district. The first premium was paid from the contributions from CSR partners and NGOs.

Embracing digital channels

The Goalpara administration has used its social media channels to disseminate information about the outbreak and lockdown restrictions. The pandemic and lockdown measures have also brought with them the need for new or expanded services with digital components, like the home delivery of groceries.

Before COVID-19, home delivery of essential goods was not popular in Goalpara. It became a necessity when the lockdown was imposed in the district. The district administration mobilized developers in Goalpara to design BG – Bazaar of Goalpara, a new app for home delivery of food and essential items during the lockdown. Besides, contact numbers for food shops and vegetable sellers were circulated through social media to facilitate ordering.

Before COVID-19, home delivery of essential goods was not popular in Goalpara. It became a necessity when the lockdown was imposed in the district. The district administration mobilized developers in Goalpara to design BG – Bazaar of Goalpara, a new app for home delivery of food and essential items during the lockdown. Besides, contact numbers for food shops and vegetable sellers were circulated through social media to facilitate ordering.

The district administration took several steps to overcome the initial resistance from shopkeepers. These include meetings, mentoring for the adoption of the new approach, and monetary incentives and vehicles for retailers to help them deliver services in the district.

Goalpara has also encouraged a “Learning from Home” initiative to revamp the ecosystem of public education in Goalpara. At the time of writing, this campaign engaged 1,500 teachers with 60 officials and benefited 10,000+ students. The administration established an official YouTube channel to promote learning where the modular learning videos based on the curriculum are consolidated, reviewed, and uploaded. A plan has been chalked out to make the channel more accessible to students with structured content. To make the digital adoption easier, teachers receive digital pedagogy training, courtesy UNICEF. The training courses includes the development, mapping, and delivery of the content. More than 90 teachers had been oriented on online safety, monitoring, and psychosocial health.

Solve immediate needs

Before community engagement and digital channels can be harnessed effectively for the benefit of the population, people must have their nutritional and health and hygiene needs covered. Here, Goalpara acted early to ensure the availability of food and essential items. Vans were deployed to each ward to sell vegetables, fruit, and milk on alternate days, and agreements were made with stores to make vegetables with longer shelf-life, like potatoes, onions, and ginger available. These measures were accompanied by public communication to ensure that information on the availability of essential goods was widely known and that panic around potential shortages did not arise.

Similarly, the production of sanitizers and protective equipment is not useful without a coordinated effort to deliver them where they are needed and ensure their proper use. To this end, the district has made handwash facilities available at essential service outlets, public areas, and particularly in “containment zones”, where COVID-19 cases have been identified. These are sanitized regularly and social-distancing circles have been marked for those queuing at grocery shops, ATMs, and pharmacies. Finally, the district has mandated that everyone should cover the mouth and nose with masks or gamusa (traditional cloth) in all public places.

Similarly, the production of sanitizers and protective equipment is not useful without a coordinated effort to deliver them where they are needed and ensure their proper use. To this end, the district has made handwash facilities available at essential service outlets, public areas, and particularly in “containment zones”, where COVID-19 cases have been identified. These are sanitized regularly and social-distancing circles have been marked for those queuing at grocery shops, ATMs, and pharmacies. Finally, the district has mandated that everyone should cover the mouth and nose with masks or gamusa (traditional cloth) in all public places.

Uncertainty has been a hallmark of the past weeks and months for many people over the world. Yet as districts like Goalpara act quickly to protect their populations from the worst effects of the pandemic, we have the opportunity to learn something important from their ideas and successes. Preparation for whatever will come can now be based on understanding how these measures have mitigated the effects of COVID-19 and the lockdowns for the most vulnerable. We can now learn how the measures can be further developed and refined to protect them now and in the future.

* MSC District Financial Inclusion Coordinator (DFIC) for PEFI project working in Aspirational District of Goalpara, Assam

[1] Aspirational Districts have been identified as pockets of under-development across the country and the Government of India is implementing a program to ensure their rapid transformation. Anchored by NITI Aayog, the Aspirational District has been instrumental in breaking the vicious cycle of low development and low motivation in the 112 under-developed districts of India.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on CICO agents- Uganda report

MSC conducted qualitative research with cash-in/cash-out (CICO) agents in Uganda to understand their needs, attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. This included the understanding agents had of the pandemic’s impact on their families and businesses. MSC also sought to understand their strategies to minimize threats and maximize business opportunities in these trying times. The research revealed that most agents are aware of the pandemic and take precautions to prevent its spread but fear a negative impact on their businesses. The low volume and value of transactions have managed to significantly reduce their income. As a result, many have begun to use their capital to meet their basic needs. Our report also offers ideas for additional support to these agents and efforts to help them recover and enhance rebuilding efforts once the crisis is over. Read to explore the full impact of COVID-19 on CICO agents in Uganda.