Leveraging the opportunities that technology offers, fintech has proven their potential to disrupt financial services to serve the mass market – including low- and middle-income customers. Increased adoption of smartphones, greater access to the internet, and growing comfort in using technology have given rise to many promising fintech innovations. However, even the most innovative approaches can fail to gain traction in an economy that’s been brought to a standstill by the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s why, as the financial services industry continues to grapple with growing economic uncertainty, fintechs are redrawing their strategy to weather this perfect storm.

In this article, the first of a two-part series, we’ll discuss the challenges and opportunities that the pandemic brings to fintechs—both small and established ones— in emerging markets, and what they can do to survive it. In the second article, we’ll look at seven approaches that stem from our initial studies, which these fintechs have utilized to overcome the challenges brought forth by the crisis.

Challenges are unprecedented, but opportunities exist

With over 5.7 million confirmed cases across 213 countries and territories and no clear sign of decline in many regions, COVID-19 has shocked both demand and supply across the global economy. Governments around the world have implemented aggressive lockdowns and social distancing measures which, though necessary, have disrupted logistics and supply chains, impeded customers’ ability to make purchases, and resulted in a global slowdown in access to capital. The International Labor Organization estimates that the pandemic will increase global unemployment by 305 million in the current quarter (Q2 2020). According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, it will slash global economic output by US $8.5 trillion over next two years and cause 34.3 million people to fall below the extreme poverty line in 2020. And these are just initial estimates.

However, these unprecedented circumstances have led to some unexpected opportunities for fintechs. At a high level, as people minimize personal contact, we foresee a tremendous opportunity for growth around a variety of digital financial services. Some services that could gain traction during the pandemic include peer-to-peer payments, merchant payments, consumer and business lending, and health and life insurance. However, fear, anxiety, and quarantining will also hurt consumer sentiment, leading to overall weak demand. But these obstacles might also present fintechs with an opportunity to develop innovative solutions to help people, businesses, and the government to manage their finances and lives better.

Fintechs can help communities weather COVID-19

At MSC, we believe that every challenge is an opportunity. This view resonates especially with fintechs that have been at the forefront of the revolution of financial services for more than a decade. Our partnership and close, ongoing association with promising fintechs under the Financial Inclusion lab have provided valuable services to more than 1.5 million low- and middle-income (LMI) households in less than two years. This has strengthened our belief that fintechs can play a crucial role in addressing the imminent social and economic challenges that LMI communities face.

Given the extent of the pandemic and its likely impact on fintechs, the sector must be rebuilt once the crisis starts subsiding. To support this process, we must first take a deep dive into the financial, business and operations management of fintechs in emerging markets to understand the impact of the pandemic.

To assess the challenges and opportunities that face fintechs, MSC kick-started a thematic research exercise across six countries in Asia and Africa, covering both smaller startups as well as bigger and more established players. Our research is based on (sometimes referred to as longitudinal data), and will be carried out over three phases spanning nine months—“now,” “intermediate” and “recovery.” All three phases of research will focus on Bangladesh, Côte d’Ivoire, India, Indonesia, Senegal and Vietnam.

The pandemic has challenged the very existence of fintechs

we have interacted with a wide range of fintechs, investors, policymakers and industry associations across these six countries to understand the nature and extent of the early effects of the pandemic. The abruptness and spread of this extraordinary event have caught the fintech ecosystem off-guard. This has challenged the prevalent investment strategies, business models and distribution rails that have fueled the growth of these fintechs so far.

COVID-19 is causing five key challenges for fintechs:

- Weak investment climate: Global funding to fintechs, which until the crisis was at record levels, has started to decline – both in terms of the number of deals and their dollar value – as investors are contemplating new risk mitigation measures. Some of the venture capital and private equity firms in our focus markets are considering which fintechs to continue funding and which to let loose, as they seek safety with a “,” moving capital away from riskier startup investments and towards larger, more established incumbents. Fintechs, which could earlier raise significant capital just on the promise of growth, now need to focus on profitability and positive cash flows to build the confidence of investors.

- Subdued policy and industry response: As funding sources dry up, struggling fintechs may be forced to seek collaboration, investment or acquisition with deal terms expected to swing in favor of the acquirers. While policymakers and industry associations are working on short- to long-term policy responses to enable fintechs to cope with the crisis, they do not have a playbook to guide them. There are still no clear guidelines or stimulus packages from policymakers or industry associations to help fintechs cope with the crisis.

- Falling transactions and dip in revenues: Our focus markets have begun to experience the onset of an economic slowdown due to restricted mobility, weak consumer sentiment and reduced business spending. Fintechs with transaction-and volume-based revenue models are witnessing a decline across all product categories. Minimizing fixed costs, while ensuring that most spend is variable, is the priority for all fintechs. Weak transaction volumes will not justify high customer acquisition costs based on large marketing expenditures and loyalty-based incentives. Fintechs need to revisit their strategies on how to retain existing customers while adding new ones to the pool.

- Limited business operations: Restricted mobility due to lockdowns has halted the field operations for most of the fintechs in our focus markets. It has had an impact on vital business processes, such as in-person verification to acquire and onboard new customers for credit fintechs and insurtechs, cash-in/cash-out transactions and rebalancing liquidity at agent outlets for players that depend on agent networks, and delivery of non-essential goods for established fintechs. Transitioning these processes to the digital mode and retraining staff will require considerable efforts from some of these fintechs.

- Employee retention and management: Many fintechs – especially the smaller, bootstrapped ones – are finding it difficult to retain employees. While some have started to implement softer measures, such as salary cuts, others are exploring stringent options, such as putting employees on furlough or lay-offs. Established fintechs are struggling to redesign internal operations to configure remote working, and to update policies to ensure the safety and health coverage of their staff.

Innovation can help fintechs unlock opportunities

Admirably, fintechs across these emerging markets are gearing up to respond to these challenging times. For instance, they have been adapting their business models and operations by eliminating variable expenses, such as hiring and marketing. They have also been preserving cash flow and runway by lowering fixed expenses, such as office space rentals. Some have been building new tools and services for remote customer acquisition and onboarding, while others are offering existing services with innovative tweaks.

One such example is PayAgri, an Indian agri-fintech that is part of the Financial Inclusion Lab, run jointly by CIIE.CO and MSC. Over the past few weeks, PayAgri’s team has been working around the clock to meet its mission — to offer market and financial linkages to farmers and farmer producer organizations. When most other startups are losing their customers with every passing day, PayAgri’s customer base of farmers needs them more than ever. Since the outbreak of the pandemic in India, the buyers’ payment cycle for agricultural produce has dropped from seven days to zero (cash and carry), and PayAgri has continued with its practice of making upfront payments to farmers at fair market prices upon collection of produce. This is the most critical value-add to the farmers it works with in these unprecedented times. Additionally, unlike many other fintechs that have laid-off their staff or put them on furloughs, PayAgri is planning to hire more people. It looks forward to serving more farmers, coming up with more innovative business ideas and expanding its business in the months and years ahead.

Along with PayAgri, an increasing number of fintechs, both big and small, are thinking and evolving to serve the low- and moderate-income community more meaningfully as the pandemic progresses. However, to stay relevant and build resilience, these fintechs need to dial down their costs, manage the squeeze in working capital, retain employees in a stricter environment, and continue to innovate.

In the second part of this series, we will look at seven specific approaches that fintechs are adopting to overcome the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis.

The blog was also published on Next Billion on 1st of June, 2020

The Internet plays an immense role in Dhanshree’s life. Her active use of the Internet and social media facilitates her ability to multitask. She uses

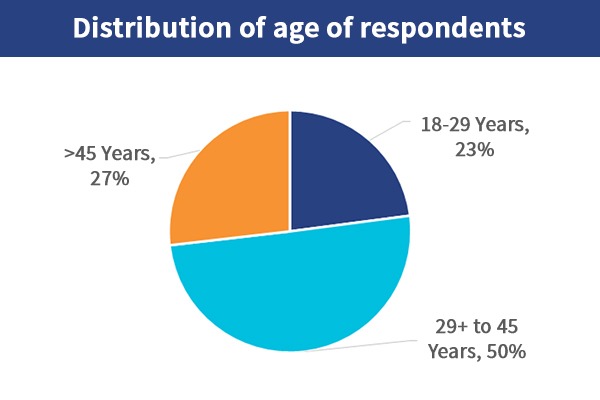

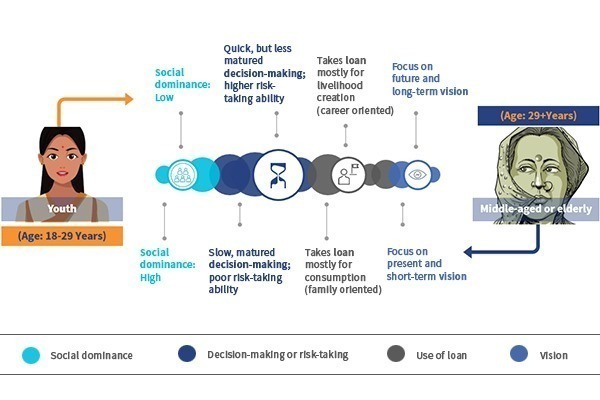

The Internet plays an immense role in Dhanshree’s life. Her active use of the Internet and social media facilitates her ability to multitask. She uses  The respondents from the middle-aged category expressed a limited desire to take calculated risks, start enterprises, or pursue livelihood opportunities owing to their existing responsibilities to grow their families and care for children and the elderly.

The respondents from the middle-aged category expressed a limited desire to take calculated risks, start enterprises, or pursue livelihood opportunities owing to their existing responsibilities to grow their families and care for children and the elderly.

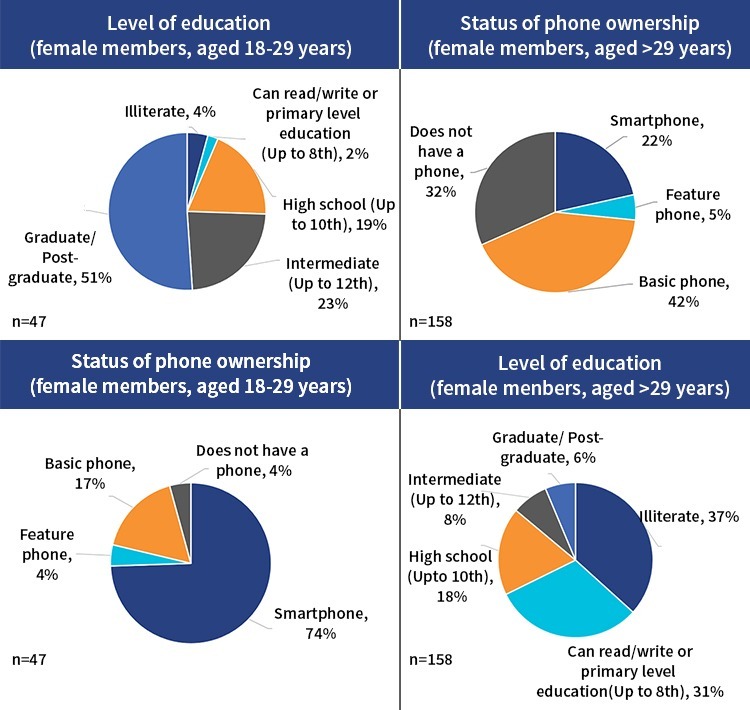

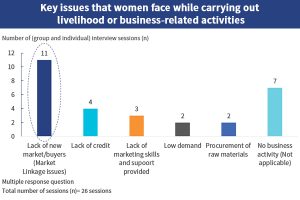

We often see that more than ever before, young rural female SHG members are more engaged in social, financial, and civic issues that affect their communities. During our research, we found that, for the most part, young female SHG members took care of all book-keeping activities and bank-related work for the group. However, when it comes to self-growth, these young members find it difficult to seize opportunities to lead livelihood activities due to a range of complex socioeconomic issues. Our interactions with many of these young female members suggest that in their start-up activities, many lack proper access to markets and human resources, are unable to promote their products, and subsequently face low product demand.

We often see that more than ever before, young rural female SHG members are more engaged in social, financial, and civic issues that affect their communities. During our research, we found that, for the most part, young female SHG members took care of all book-keeping activities and bank-related work for the group. However, when it comes to self-growth, these young members find it difficult to seize opportunities to lead livelihood activities due to a range of complex socioeconomic issues. Our interactions with many of these young female members suggest that in their start-up activities, many lack proper access to markets and human resources, are unable to promote their products, and subsequently face low product demand. Significant improvements in “access to markets” are needed for SHG members to be able to access livelihood opportunities and create sustainable development. Many young SHG members who have started businesses have faced problems and economic losses due to poor access to markets. “Access to finance is not a problem for me but access to markets is. How can I sell and deliver my handmade products in far off places? Why do I have to depend on my brother to sell these items? He can easily roam around day and night on his motorbike but I cannot. It is difficult for young women—we have some limitations,” rued a young SHG member who is running a business selling handmade paper envelopes.

Significant improvements in “access to markets” are needed for SHG members to be able to access livelihood opportunities and create sustainable development. Many young SHG members who have started businesses have faced problems and economic losses due to poor access to markets. “Access to finance is not a problem for me but access to markets is. How can I sell and deliver my handmade products in far off places? Why do I have to depend on my brother to sell these items? He can easily roam around day and night on his motorbike but I cannot. It is difficult for young women—we have some limitations,” rued a young SHG member who is running a business selling handmade paper envelopes.