This video gives market insights from Kenya: The number of people who have borrowed digital loans, the portfolio quality of these loans as well as the number of people negatively listed on the credit reference bureau

Blog

Mobile internet access – the next frontier for ‘Tech’

The ‘tech’ revolution depends on internet access

The tech revolution is being heavily promoted as the answer to many of the development challenges with which we have been struggling for so many years. These advanced tech solutions can potentially address pressing issues related to financial, agricultural, educational, health, and enterprise sectors, among others. The vast majority of these advanced tech solutions, however, require connectivity to realise their full potential. They need both access to 3G+ or internet coverage, which is often limited in rural areas, as well as a phone that has unfettered access to the Internet.

Smartphone penetration has been rising – slowly

The past five years have seen a rapid fall in the prices of smartphones. Some of the best deals in Africa are available in Kenya. Here, the average price of a smartphone has more than halved from the KSH 23,100 (USD 270) in 2013 to KSH 9,700 (USD 95) in 2016. The lowest priced X-Tigi P3 smartphone is being sold on the Jumia e-commerce site for KSH 2,799 (USD 27). In April 2017, The Business Daily reported that “Smartphone penetration in Kenya has grown to more than 60% of the population over the past five years thanks to the influx of affordable phones.” It also noted that “smartphone sales were heavily concentrated in urban areas”, which is hardly surprising given the 3G+ coverage in the country.

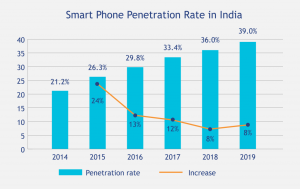

But Kenya is a positive outlier. GSMA predicts that the global mobile internet penetration may only rise from the 2017 level of 43% to 61% by 2025. Unsurprisingly the rates are lower for sub-Saharan Africa, which was at 21% in 2017 and is predicted to rise to 40% by 2025. In India, the rapid rise in smartphone penetration rates are projected to fall quite significantly over the next couple of years – and potentially further beyond (see graph). Once again, the urban areas have now been largely saturated, leaving rural areas with little or no 3+G coverage as the potential market.

Furthermore, there are three critical issues that we should remember in looking at the data:

- Penetration rates typically double-count people with more than two SIM cards – and thus overstate the effective penetration rates. (Although, you may argue that if husbands and wives share a mobile internet connection this would result in an understatement).

- Inevitably, the more affluent segments of society hold the vast majority of these mobile internet connections.

- The data hide significant and troubling gender disparities. In its Mobile Gender Gap 2018 report, the GSMA notes that: “Women in low- and middle-income countries are, on average, 10% less likely to own a mobile phone than men, which translates into 184 million fewer women owning mobile phones. Over 1.2 billion women in low- and middle-income countries do not use mobile internet. Women are, on average, 26% less likely to use mobile internet than men. Even among mobile owners, women are 18% less likely than men to use mobile internet. The gender gap is wider in certain parts of the world. For instance, women in South Asia are 26% less likely to own a mobile than men and 70% less likely to use mobile internet.”

Navigating smartphones is not easy

We should also note that smartphones are not as easy or intuitive for low-income segments, and particularly for the oral – illiterate and innumerate people. In the words of the Digital Skills Observatory, “Without the right skills, smartphones can exacerbate adoption challenges, instead of alleviating them … The environment that people discover through their smartphones is controlled by a few powerful organizations who play a big role in the apps and services people use, and shape the way people communicate with one another. Inexperience with this world disrupts confidence in smartphone use and causes confusion about digital identity and content consumption and creation. As people begin to use and explore their devices, apps pre-installed by manufacturers or operators cause uncertainty. Their origin is unclear, their purpose is mysterious, and their permanence is frustrating.”

Furthermore, the uptake and use of digital financial services require more than just digital skills to navigate this new world. In addition to ability, users also need awareness, access, and, above all, a real need to stimulate uptake and use. The limited use of basic mobile money services highlights this. The GSMA’s State of the Industry Report 2017 notes that of the 690 million registered mobile money accounts across the globe, only 168 million (24%) were 30 day active.

A substantial proportion of growth in penetration will be smart feature phones

But there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that “smart feature phones” (like the X-Tigi P3) will drive a significant proportion of the rises in mobile phone ownership. In its Q1 2018 report, International Data Corporation (IDC) noted that “the smartphone market will continue to grow in Africa … However, sales are unlikely to reach the rates seen a year or two ago now that many urban markets are becoming saturated.”

As Jake Kendall and Arunjay Katakam highlight in their excellent blog ‘Long Live the Feature Phone’, “… the trend is continuing, YoY, the feature phone market was up 11.5%. Feature phones still constitute a significant 62.2% share of the total mobile phone market (from 56% the year before)”.

These smart feature phones like the Jiophone in India (see box) drive growth because they address several pain-points experienced by less affluent customers who have tried low-end smartphones. A recent Mozilla report highlighted that low-end smartphones have limited RAM, which prohibits running many fintech apps. In addition, they also typically have hopelessly short battery lives, screens that shatter easily, and a persistent problem with ‘fat finger error’ that makes them almost unusable. Furthermore, the cost of data needed to make fintech transactions is usually prohibitively expensive. Indeed, in our fieldwork, we have seen some men in Africa proudly carrying prestigious smartphones but using them only to make or receive calls and SMSs.

However, as Jake Kendall and Arunjay Katakam point out “Probably the most critical limitation is that feature phones do not have an open app store like smartphones. This dramatically limits the ability of 3rd party developers to create new apps and features that can be deployed on these phones. At present, the feature phone landscape is quite broad: there are more than 1,348 models available from 76 manufacturers. These phones run on a myriad of operating systems including several proprietary ones making it very difficult to write apps for these phones as each app would have to be recoded and customized for each phone.”

With even Facebook and WhatsApp rolling back efforts to cater to the feature phone market, it is reasonable to assume that “tech” apps will not be to navigate this challenge … and thus smart feature phones will not be able to run these apps.

So what does this mean for “techs”?

This has significant implications for techs that seek to serve the mass market. Limited mobile internet connectivity has left many digital credit providers relying on minimal top-up and mobile money transaction data to make credit decisions. The results have not been pretty.

Tech providers will need to build systems that use only feature phones such as the MasterCard Lab’s 2KUZE which “places the seller and buyer at an open field of interaction, where prices are negotiated, deals sealed and the agent goes to pick the produce, and once it is received, payment is made either in mobile money, cash or bank payment.” This could, of course, create a much deeper digital footprint for farmers who regularly use the platform, thus improving the data for credit decisions.

The alternative is a judicious mix, with the more sophisticated transactions conducted at agents with smartphones or tablets located in hubs where 3G+ is available and the basic service transactions conducted using feature phones. In the context of fintech, for example, for several years now, MicroSave has advocated differentiated agent outlets. Differentiation involves:

- Relatively sophisticated (usually exclusive and dedicated) sales agentsresponsible for selling products, on-boarding customers, and conducting larger value transactions; and

- Basic (usually non-exclusive and non-dedicated) service agentsresponsible for conducting, typically smaller, cash in and cash out (CICO) transactions.

Sales agents would be based usually in higher footfall market towns, with easier access to both 3G+ coverage and bank branches for rebalancing and support – thus allowing them to manage higher value transactions and sales of sophisticated products. To do so they would use either a smartphone or tablet or both. Basic service agents in more remote villages with only 2G services can conduct basic CICO transactions using feature phones.

Similar approaches can be used for agriculture (see The white spaces of the digital divide: 3G+ haves and have-nots), health, education, enterprise, along with a host of other areas.

The white spaces of the digital divide: 3G+ haves and have-nots

In previous blogs, we discussed the seven key drivers of digital exclusion in emerging markets. This one examines the implications of the observation that in most rural villages, the infrastructure to support fintech, agtech, healthtech or any other form of “tech” remains inadequate. This is because these ‘techs’ depend on users being able to access app stores and the Internet – usually through smartphones, which we discuss in ‘Mobile Internet access – the next frontier for ‘Tech’’. Efforts are underway to expand access.

|

The World Economic Forum has developed the ‘Internet for All’ global initiative. It aims “to develop models for large-scale public-private collaboration that accelerate internet access and adoption”. Its initial work targets 75 million Africans in the Northern Corridor countries of Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Uganda.

The initial work was to commission research from Boston Consulting Group, which concluded, among other things, “Infrastructure is a big hurdle for many countries, especially those that are poor or with large rural or remote populations. Many developing markets require massive investment to move up to more advanced mobile technologies.” Where is this investment going to come from?

To date, until (and perhaps even when) companies deploy new technology such as balloons and nano-satellites, infrastructure problems are likely to persist. As a result, a significant proportion of rural populations will remain without access to the Internet and thus most of fintech. This is because 3G technology is more expensive for providers – not least of all because of its higher frequency and thus reduced coverage (see box).

|

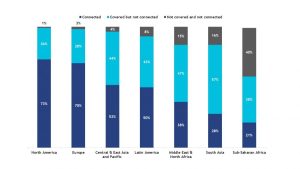

In a compelling illustration of the scale of the problem, this Intelsat graphic from their white paper on Overcoming Barriers to Providing Mobile Coverage Everywhere shows the situation in 2019.

In simple terms 40% of Sub Saharan Africa and 16% of South Asia have no coverage – and in both cases only about a quarter of the population is covered and connected. Beneath this high-level analysis, population-dense areas are served with 3G+ and the relatively rural areas are left with 2G or, more typically, no G. In the words of one Kenyan telecommunications expert, “3G is only available in major towns where providers are able to make more profit and so rural markets will take years before experiencing 3G or 4G technology”.

As a result, we will see an increasing divide between communities that have access to 3G+ technology and those left with 2G or no G. For those privileged to live within the 3G+ corridors, a wide range of emerging techs have the potential to significantly improve their lives – particularly if developers start to focus on serving the needs of the mass market.

In this context, MicroSave has been working on an approach in India to precision farming, which uses data on the following aspects:

- The landholding, tenancy status, and crops cultivated (from digital land records(see also Land record digitisation-Exploring new horizon in digital financial services for farmers. Part 1) or self-reported when procuring subsidies and inputs);

- The nutrient deficiency in soil and recommended fertiliser dosage (from the Government of India’s Soil Health Card scheme);

- The crops being cultivated (through Kisan Credit Card, seed purchases from agro-input stores including Primary Agriculture Cooperative Societies, and satellite or drone images);

- Fertilisers and agrochemicals purchased (through tracking purchases from agro-input stores and the platform managed by the state governments);

- PM Fasal Bima Yojanaor Prime Minister’s crop insurance scheme (tracking weather patterns likely to have an impact on crops through the Automatic Weather Station, satellites and databases);

- Market prices and inflow of commodities (from the e-NAM system);

- Optimising logistics for pick-up or delivery of the harvest and assessing the storage requirements.

This wide range of information will not only allow financial institutions to offer credit, insurance, and savings products based on high-quality insights into the farmers’ behaviour, but also allow tailored packaging of practices for each individual farmer. All farmers would receive carefully timed, personalised SMS reminders on when and what to cultivate and harvest based on weather conditions, availability of water, and recommended dosage and applications of fertiliser and agrochemicals. Specifically tailored AI and chat-bots would send these reminders according to the landholding, soil health, and cropping pattern of the farmers.

In addition, farmers will receive alerts when pests threaten their crops. So for instance, in case of maize borer attack in a district, all farmers that grow maize in the adjoining districts will receive warnings and recommendations based on Integrated Pest Management principles, telling the farmer how to respond. Monitoring compliance with these alerts, or at least purchase of the relevant pesticides and application techniques, will feed into the farmer’s digital locker and thus when the farmer chooses to open their digital locker provide financial institutions with additional information on how the farmer conducts business.

Similar systems will, no doubt, emerge to support education, health, and a range of other livelihoods … only for those that have access to 3G+ and the Internet. But not for those stranded in the world of 2G or no G.

There are, of course, important implications for financial institutions that serve these communities. We have already seen relatively simple algorithm-based systems used to offer credit to those with smartphones. But these will increase in sophistication and their ability to use customer data to make informed lending decisions … and thus reduce both interest rates and waiting time to receive loans. Microfinance institutions and others that lend into rural areas may well see their high-value clients who are often located in 3G+ coverage areas move in part, or in full, to these digital credit providers. They would then be left struggling to serve their remaining lower value clients with traditional analogue, or at best 2G, mobile money-enabled systems.

A solution, in part at least, may lie in seeking to combine the 3G+ and 2G worlds. This would ensure that in the precision agriculture example above, the data is uploaded and managed at the agro-input store, which is likely to be in a 3G+ coverage area and have access to either a smartphone or tablet or both. The farmer would then receive their tailored SMS alerts through 2G coverage in their village. This reflects an approach that MicroSave suggested in The Clear Blue Water on the Other Side of the Digital Divide. Similarly, in the context of financial inclusion, we will need to see a separation of sales and service agents as has been outlined in The Agent Profitability Conundrum in India – Time for Differentiated Agents? This would allow sales agents, who offer a range of products and services – perhaps as diverse as outlined in A Strategic Approach for Next-Generation DFS Agent Networks, to operate in 3G+ areas, and serve agents who conduct basic cash-in and cash-out transactions to operate in more remote coverage 2G areas.

For this, and a variety of reasons highlighted in Can Fintech Really Deliver On Its Promise For Financial Inclusion?, in the words of Jake Kendall, of the DFSLab “… it is safe to say that feature phones are here to stay, and a sizeable proportion of low-income individuals will continue to use feature phones for the foreseeable future.” Amid the excitement of app-based techs, we need to plan for the 2G and no G world if we are to address Sustainable Development Goals for rural populations through technology.

Disruptive Innovations in Fintech can deliver value to Poor

In her address at the 2017 Mastercard Foundation Symposium on Financial Inclusion, Tamara Cook, Head of Digital Innovations at FSD Kenya states that disruptive innovations can respond to the daily financial service needs of the poor people.

Can Disruptive Innovation Respond to the Financial Service Needs of Poor People?

In his address at the 2017 Mastercard Foundation Symposium on Financial Inclusion, Graham Wright, Director, MicroSave asks how fintech providers plan to solve the financial service needs of billions of poor, innumerate and illiterate people across the globe.

A Qualitative Study of Producer Organisations in Select Geographies in India

Different types of farmers and other producer cooperatives or collectives have been in existence in India for years. These collectives are increasingly playing a vital role through advantages of economies of scale and scope. They can be suitable units for interventions to improve incomes and well-being of smallholder farmers, share croppers and landless labourers. Increasingly, there is a sharper focus on nurturing and building robust farmer collectives at scale.

However, very little data or granular insights are available for farmer collectives. MicroSave undertook a short study to fill this information gap. This study covered producer organisations (POs), particularly farmer collectives (FPOs), across seven states in India. The main focus was to assess the current state of these collectives, understand their needs and aspirations and assess the gaps. The report brings out insights on PO forms, organisations, structures, management, governance, operations, business performance, earnings, needs, expectations, maturity levels and several other important aspects regarding farmer collectives.