East Africa has been termed as one of the fastest growing trading blocks in the world. Agriculture plays a key role in this region as it contributes to about 25-40% in each of the Eastern African economy GDP.

Blog

Closing the Gender Gap: Opportunities for the Women’s Mobile Financial Services Market in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s financial sector has undergone rapid growth and has embraced technology solutions to improve the financial inclusion of the general population. However, certain segments remain disproportionately unbanked and financial inclusion for women remains a challenge, with only 26 percent of women owning a bank account (Global Findex 2014). Formal financial institutions have limited reach in rural areas, which restricts the spread of basic financial services among the rural population. Given such constraints and high mobile penetration, mobile financial services (MFS) can be a powerful catalyst in the near future, to bridge the gap between financial institutions (FIs) and those with fewer financial means or access to bank branches. Here, MFS is defined as the use of a mobile phone to access financial services and execute financial transactions. This includes both transactional services (such as funds transfer and payments) and non-transactional services, such as viewing financial information on a user’s mobile phone. This report aims to catalyse the financial inclusion of financially underserved Bangladeshi women through improved MFS adoption. It contains extensive, in-depth research to understand the needs and requirements of women MFS users. The report consists of three distinct divisions:

1. The women MFS market’s potential in Bangladesh. This division provides an extensive set of market data and analysis on overall women’s market potential, and projected growth.

2. Product preferences of female MFS users in Bangladesh. This division identifies MFS product features that will appeal to women, and different segments of women users’ product preferences.

3. Market assessment for female agent acquisition. This division offers a roadmap to help MFS providers build and expand a network of female agents.

This report was originally published by the International Finance Corporation.

Credit Risk Management

Continuous credit risk monitoring remains one of the biggest challenges for many financial institutions. Yet its management is critical to a financial institution’s sustainability

Enhancing education finance: A perspective of the financial journey of low- to medium-cost private primary schools in kenya

The chatter and sounds of students playing in the school ground echoes in the distance. Peter, the school owner, looks at the children through his office window with pride. It seems like just the other day when he resigned from employment as a teacher to establish his own school. To finance the start-up, he used his savings to lease a piece of land and construct semi-permanent structures to serve as classrooms. Five years later, Achievers Academy in Githurai has grown from a student population of 20 to 250 with a stellar performance record.

The future seems bright and Peter has an ambitious vision for the growth of the school. The school management recently acquired a piece of land and has embarked on a project to build classrooms. Additionally, there are plans to acquire assets, such as two school buses and expansion to a new branch in Ruiru. These projects require external financing. Peter is multi-banked but needs a partner that would offer both financial and advisory solutions for his plans.

Peter’s example is typical of low- to medium-cost private primary schools in Kenya. According to a 2014 report by the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development, there are approximately 8,000 private primary schools in the country. These schools have been mushrooming rapidly due to the extraordinary demand fuelled by a need for “quality” education. There is a widespread perception that private primary schools offer better education compared to public primary schools. However, private primary schools face numerous challenges, especially when accessing finance. MicroSave conducted a study to understand how low- to medium-cost schools meet their financing needs. In this blog post, we explore the estimated financing demand, financial journey, challenges, behaviour, current coping mechanisms, and recommendations for financial partners that wish to serve this niche segment in a profitable and sustainable manner.

Peter’s example is typical of low- to medium-cost private primary schools in Kenya. According to a 2014 report by the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development, there are approximately 8,000 private primary schools in the country. These schools have been mushrooming rapidly due to the extraordinary demand fuelled by a need for “quality” education. There is a widespread perception that private primary schools offer better education compared to public primary schools. However, private primary schools face numerous challenges, especially when accessing finance. MicroSave conducted a study to understand how low- to medium-cost schools meet their financing needs. In this blog post, we explore the estimated financing demand, financial journey, challenges, behaviour, current coping mechanisms, and recommendations for financial partners that wish to serve this niche segment in a profitable and sustainable manner.

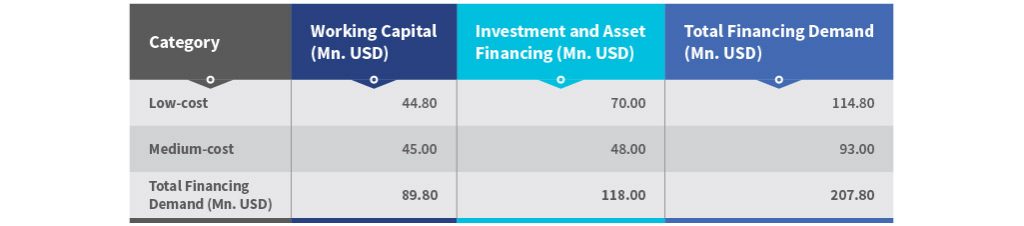

Based on our research, we found that low- and medium-cost primary schools require both working capital, investment, and asset finance. The major difference between the two categories is in the size of the finance needed. According to our analysis and estimation of available data, the current demand for finance for low- and medium-cost schools is approximately USD 207 million. This indicates an opportunity for financial service providers. The table below further illustrates the demand for low- and medium-cost schools:

Financial Journey of Low- to Medium-Cost Private Primary Schools

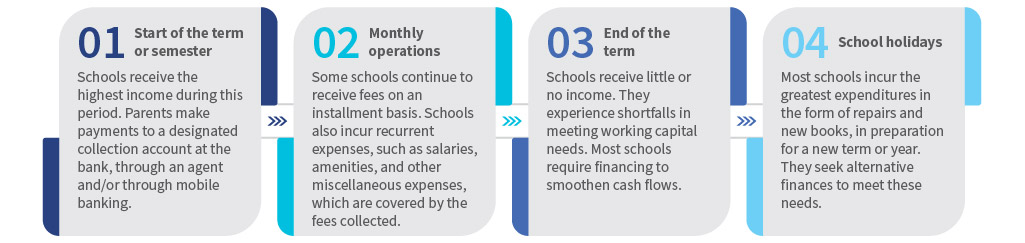

In Kenya, a school year has three terms or semesters. Each term comprises three to four months. Generally, schools manage finances on a term- or semester basis, as depicted below:

As seen in the graphic, as the term ends, low to medium-cost private primary schools struggle with working capital. In addition to term-related operations, these schools have annual plans to develop and expand the school. To finance such long-term projects, most school owners take out personal loans from formal financing sources. The size of these loans is limited by the borrower’s personal income flows and thus hinders the growth of the school.

Financial Challenges of Low- to Medium-cost Private Primary Schools

The financial challenges faced by low- and medium-cost private primary schools in their financial journey include:

- Limited capital for long-term investments: Low- to medium-cost private primary schools collect fees that they largely use to cover recurrent expenses. They, therefore, have limited capital for long-term investments, such as the acquisition of school assets and expansion of infrastructure.

- Inadequate access to formal finance: Formal financial institutions have stringent loan requirements, such as hard collateral and compulsory down-payments for asset financing. These requirements limit the ability of schools to access growth-related finance from formal financial institutions.

- Weak financial management skills: Most low- or medium-cost private school owners are former educationists. They have limited financial management and operational skills to drive their vision into action. This poses various challenges in planning and collection of school fee income and managing school fees’ arrears.

- Weak relationship with financial institutions: Most schools have transactional relationships with financial institutions, which reduce the benefits they may derive from these relationships.

- Weak loan structuring by financial institutions: Most formal financial institutions structure loan repayments on a monthly basis. However, schools receive their incomes on a termly or semester basis. This mismatch in the schools’ cash-flows and repayment schedules leads to difficulties for the schools in serving loan facilities.

Financial Behaviours of Low- to Medium-cost Private Primary Schools

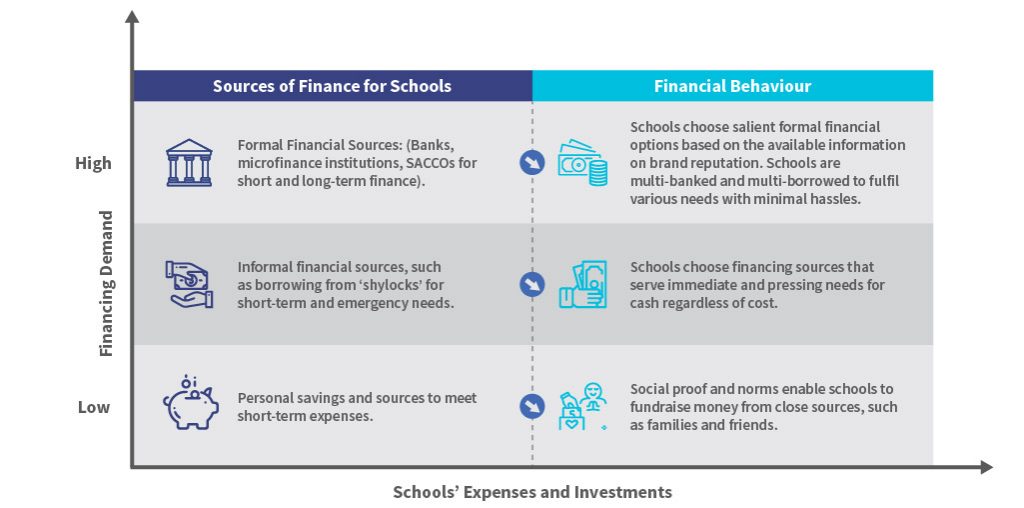

The challenges experienced on the financial journey influences the financing behaviour of these schools. In the adjoining illustration, we depict the financial demand in relation to expenses and investment, and the behaviours that affect the financing choices of the school. As the schools’ demand for financing increases, they seek and use financing from formal financial institutions. However, only a limited number of schools are able to access appropriate financing from these institutions.

As seen in the graph, schools use a combination of both formal and informal financing to fulfil their varying operational and financial needs. The demand for finance to sustain the operations and investment purposes of the schools is high and presents an opportunity for financial institutions to enter the space. However, it is critical that financial institutions understand the financial needs and behaviours of schools to adequately serve them. How can a financial institution profitably partner with low- and medium-cost primary private school owners? We list below the minimum considerations for financial institutions that are interested to serve and meet the financial needs of schools in a sustainable and profitable manner.

a) Dedicated Relationship Management

Low- and medium-cost private primary schools value a long-term relationship with formal financial institutions. This means financial institutions that target such schools may consider building this through relationship managers who are experts in school management. In this way, school owners and management can benefit from both financial and non-financial services.

b) Education Sector-centric Products with Digital Aspects

Financial institutions can develop or refine their existing products to incorporate the needs, activities, and financial behaviour of schools. For example, they can design a loan product that would account for the school fees payment schedules and period of the term or semester. Additionally, products (including collection accounts, payment platforms etc. – see below) may be accessible through various channels, such as agency banking, online banking, and mobile banking.

c) Marketing and Branding

Financial institutions that seek to finance the education segment should invest in marketing and branding to ensure that their potential customers can reach them better. These institutions can do it by reviewing existing marketing approaches to ensure consistent messaging on education finance. A financial institution may proactively engage in activities, such as advertising school education finance products, participating in private school association meetings, conducting school visits, and sponsoring school events.

d) Wallet-share Maximisation

Financial institutions can consider providing a full suite of services to meet the needs of schools. These services may include school fees collection accounts, payments and transfers, short-term and long-term credit, regular and goal-based savings, insurance, budgeting, and financial management to benefit from financing this segment.

In conclusion, low- and medium-cost private schools in Kenya present a niche segment for formal financial institutions. However, these schools face exclusion challenges due to lack of appropriately structured products, and limited outreach by formal financial institutions. Financial service providers have an opportunity to serve this segment in a profitable and sustainable manner if they build long-term relationships with schools, understand their needs, and design a suite of products that meet those needs.

David Cracknell in conversation with CGTN on the Future of Finance: Consumer Protection.

David Cracknell, The Global Technical Director was in conversation with CGTN where he covered in detail issues pertaining to consumer protection and information disclosure whilst also touching on algorithms and how they are used in the digital lending platform. Listen in for more insights on this.

Indonesia’s experiment with digitising food subsidy payments: The story so far

Background of government-to-people (G2P) payments in Indonesia

Indonesia has embarked on an ambitious programme to digitise all social assistance payments in the country by 2019. In 2017, one of the largest social assistance programmes, Raskin, was digitised and moved to cash transfers. The new, cash-based programme has been renamed Bantuan Pangan Non Tunai (BPNT). The programme piloted with 1.4 million beneficiaries in 44 cities. It will expand to 10 million beneficiaries across 72 cities in 2018.

The other programme that has been digitised is Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH), a conditional cash transfer scheme. PKH initially targeted 6 million beneficiaries in 2017. It would extend to 10 million beneficiaries in 2018. PKH has been designed to influence household incentives to participate in health and education. Under PKH, poor households receive annual payments of IDR 1.89 million (~USD 137) upon meeting certain conditions. These criteria include the attendance rate for pre-and post-natal check-ups in primary health centres by mothers, professionally assisted births, health checks for newborn children and toddlers, and school attendance records for children of school-going age.

The Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSA) implements both these programmes. The government has also been developing plans to digitise both fertiliser and LPG subsidies in the short to medium term. Estimates indicate that these programmes have 48 million and 25 million beneficiaries respectively.1 This note focusses on the BPNT programme. It summarises key findings of the operations assessment of the programme that MicroSave conducted for the Ministry of Social Affairs, Indonesia (MoSA).

The mechanism for delivery of social assistance transfers

The current scheme for social transfer of food subsidy (BPNT) has been designed to transfer the subsidy amount into the public sector bank accounts (basic savings accounts) of the scheme beneficiary. The beneficiary can then conduct transactions using the Kartu Keluarga Sejahtera (KKS) card – a debit card linked to the account. The account has sub-wallets dedicated to specific social transfer schemes. The subsidy amount for each scheme is transferred to these sub-wallets, which increases transparency for the beneficiary.

The BPNT subsidy of IDR 110,000 (~USD 7.8) per month is transferred to the beneficiary’s BPNT sub-wallet. Beneficiaries then visit designated e-warong retailers appointed by the participating banks and use the KKS card to purchase food. Under the new scheme, e-warongs can purchase specified food supplies, such as rice, egg, sugar, cooking oil, and flour from private suppliers as well as from the government food procurement and distribution agency (BULOG). This is a departure from the earlier Raskin programme, under which food was distributed through BULOG alone.

What are the key benefits of the programme?

Beneficiaries felt that the BPNT scheme has improved the quality of food items. Under Raskin, beneficiaries would receive rice from BULOG. Beneficiaries believed that this rice was of poor quality. Under BPNT, e-warongs can choose the supplier and buy locally preferred rice, which encourages beneficiaries to come to their shop. Among respondents, 89% mentioned that under the BPNT programme, they received rice that was better in quality.

In addition, BPNT beneficiaries now get more food when compared to Raskin. Under the Raskin programme, it was a general practice for representatives of village governments to distribute rice to all households in the village, even to those not entitled to receive the rice. This meant that each month, the genuine beneficiary households received much less than their share of 15 kilograms per household.

Under the BPNT programme, these leakages have been plugged largely as the money is now transferred directly to the designated beneficiary account. Of the respondents, 91% said that they could buy more food under the BPNT programme compared to the amount of food they would receive under Raskin.

Most of the e-warongs are highly satisfied with the BPNT programme, especially those who are regular grocery store owners and use their own private suppliers. These e-warongs feel that the BPNT programme has increased the footfall at their stores and has thus grown their monthly sales. Almost all the e-warongs interviewed mentioned that they wish to continue with the BPNT programme in the coming years.

What are the key challenges faced?

Although the overall satisfaction of the beneficiaries and e-warongs who exist under the BPNT programme remains high, some key operational challenges remain. We outline these challenges in the following section.

Remembering the PIN: Over 30% of the beneficiaries said that they had issues in remembering the PIN to make transactions. If they forget their PIN, they have to get a new PIN issued at the bank branch, which is both a hassle and expense for many. To avoid this, e-warong operators in a number of locations set the PIN for the beneficiaries. MicroSave found instances of all beneficiaries in a particular kelurahan (village) with the same PIN. This has serious implications for customer protection through a higher risk of fraud.

Reliability of technology: Among e-warongs, 69% reported that they have observed instances where the balances in the accounts of beneficiaries were updated incorrectly even after a transfer from the bank was completed. This suggests that the technology used by the four participating banks is still not completely reliable. If left unresolved, customer satisfaction risks being compromised.

Tracking the purchases done at the e-warong: Neither MoSA nor the banks are able to track the nature of purchases made by beneficiaries at e-warongs. An ability to track could have otherwise ensured that the beneficiaries spend the subsidy on the specified items, such as rice and eggs. E-warongs can therefore theoretically sell any item that they stock to the beneficiaries and the government or implementing agencies would not be able to detect this. In 2017, 17% of the beneficiaries mentioned that they bought non-specified items. As the programme scales, the challenge for MoSA and the participating banks would be to introduce cost-effective and scalable solutions to track the purchases at the front-end.

Limited banks involved in the BPNT program: At present, only the four government-owned banks (BRI, Bank Mandiri, BNI, and BTN) are allowed to participate in the programme. With the exception of Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI), other government banks have a limited presence in many of the geographies. BRI is the largest Indonesian bank with a wide outreach through its units and branchless banking (Laku Pandai) agents. Opening the programme to certain other banks or e-money retailers could make it more sustainable in the long run. This is because the banks may have wider branchless banking networks, while the e-money issuers may have a widespread retail presence.

In conclusion, the digitisation of the BPNT programme sets the pattern for all other social assistance programmes in Indonesia. MicroSave’s evaluation indicates that as of date, there is a high level of satisfaction among the beneficiaries and e-warongs with the programme. However, for a more sustainable scale-up, the government should prioritise the following:

- Working on constraints to create more convenient payment technologies for the poor;

- Better monitoring of the scheme at the level of the e-warong;

- Involving other banks and e-money issuers.

BPNT not only brings efficiency to one of Indonesia’s largest social assistance programmes. It also offers a promising solution to accelerate financial inclusion by compelling a large number of unbanked households to open and use bank accounts. Ensuring its success should be the focus for all stakeholders involved in financial inclusion across Indonesia.

[1]https://www.indonesia-investments.com/culture/economy/general-economic-outline/agriculture/item378