Mustika (name changed) has been the sole breadwinner of her family ever since her husband, a former factory laborer, was laid off due to the COVID-19 pandemic. She works as a nonpermanent teacher in a junior secondary school. She also takes on side hustles as a grocery reseller and a domestic helper, providing ironing services to several households.

Mustika is an active member of “Doa Bunda,” a women’s cooperative under the Pemberdayaan Perempuan Kepala Keluarga—The Female-headed Family Empowerment Foundation (PEKKA). As part of the cooperative, she commits to saving money every month consistently. She has been paying off her low-interest rate (~1%) business loan from PEKKA. Mustika reloads her e-wallet regularly to buy products in bulk on e-commerce platforms. She believes that she gets a better price on these platforms, especially using cashback promotions from the e-wallet provider.

Mustika lives far away from the city. So she prefers to use a branchless banking (Laku Pandai) agent for banking services, including money transfers, cash withdrawal, and social assistance benefits. In this way, she saves both time and money spent commuting to the faraway bank branch.

Women’s cooperatives are vulnerable to being left behind in the rapidly evolving digital economy

Data from the Ministry of Cooperative and Small Medium Enterprise (SME) in 2021 revealed 13,212 active women’s cooperatives in Indonesia. But, these are only 9% of the total active cooperatives across 34 provinces. Considering this limited representation, can women’s cooperatives achieve the four strategies the President of Indonesia set forth? These strategies include:

- Modernization of cooperatives

- Emergence of new entrepreneurs

- Integration of MSMEs to global value chain

- Scaling up of MSMEs

Among the strategies, “modernization of cooperatives” poses the most significant challenge to women’s cooperatives, especially in rural areas. Rural women’s cooperatives have limited access to information, resources, and digital tools. Typically, they are small-scale, semiformal, and are often left behind amid the charge toward digitalization.

The Minister of Cooperation and SME, Teten Masduki, mentioned that only 0.73% of all cooperatives are connected with the digital ecosystem. Women’s cooperatives play a critical role in the economic empowerment of rural women by helping them accumulate assets under their name through savings and providing small-scale finance. Seeing them left out of the movement is disheartening.

Moreover, modernization should go beyond digitizing the operational system of cooperatives. It should also encompass the development of digital banking products and services to meet the needs of cooperative members.

Women’s cooperatives can potentially be a great partner for banks to extend digital financial services to the last mile, especially to low-income women

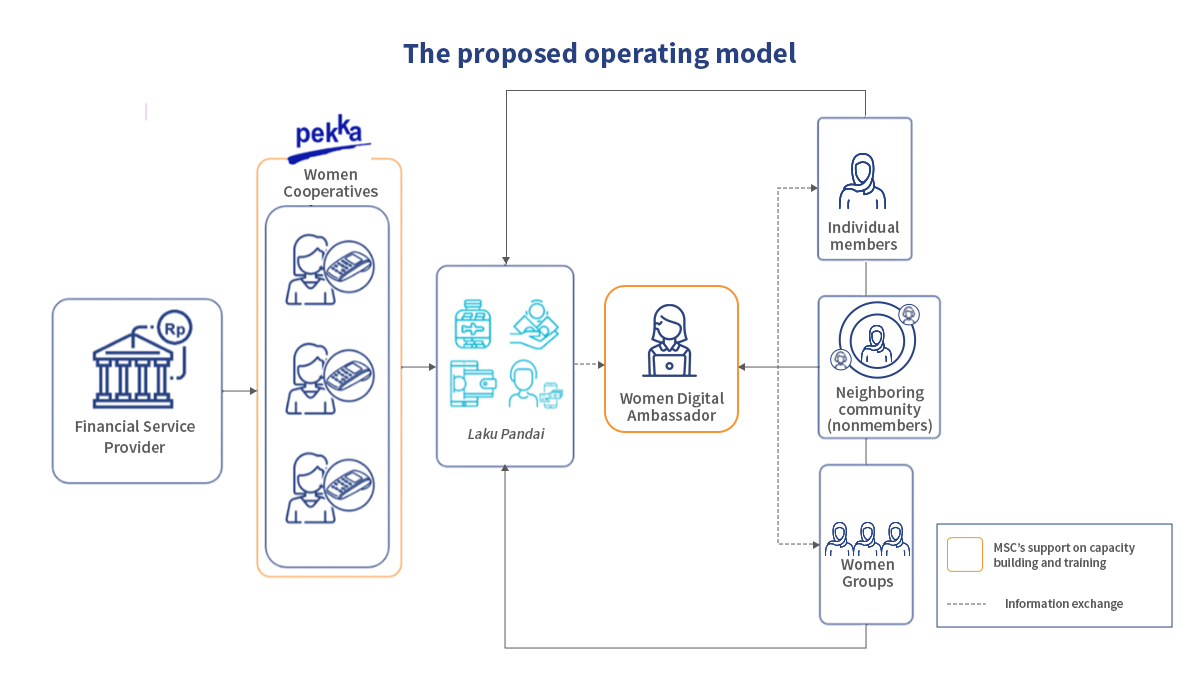

MSC and PEKKA Foundation have collaborated to enhance low-income women’s quality, uptake, and usage of digital financial services in rural areas. PEKKA runs a network of women’s cooperatives in 20 Indonesian provinces.

The pilot project will cover four districts in four provinces: Tangerang, Karawang, Pekalongan City, and Bantul. We are working to integrate the cooperative and Laku Pandai agents to provide financial products and services on a digital platform. The platform will serve the existing member base across the women’s cooperative offices during the pilot phase, and from the result, it will be expanded to other locations under the cooperative’s network.

Cooperatives that were once limited to offering basic loan and saving services can now provide their members the full suite of a bank’s financial services. They can now offer money transfer, cash withdrawal, bill payment, disbursement of cash social assistance, and People Business Credit (KUR) applications. Also, transaction fees charged by the agent are a potential source of income for the cooperatives. It can turn into residual income or Sisa Hasil Usaha (SHU) at the year-end.

The integration of Laku Pandai and cooperative

MSC’s study on female banking agents in India found that female agents create a reassuring environment for women and men to make transactions. It also noted that the acceptance and success of female agents depend significantly on social perceptions, which play a more influential role for them than their male counterparts. For instance, our research shows that most customers generally perceive male agents to be faster, more knowledgeable, updated about product features, and less prone to commit errors in the DFS business.

Although the findings reflected India’s perceptions, social norms, and culture, MSC found similar phenomena while undertaking need assessment in the pilot project locations of Indonesia. Women need another group of empowered women of higher capacity and broader insights—“influencers”—to help them adopt digital finances.

For this reason, Women Digital Ambassadors (WDAs) are recruited from the cooperative members. These ambassadors consist of women small business owners who will be equipped with knowledge and tools through training from MSC on digital entrepreneurship, selling through social commerce, and digital finances. These small entrepreneurs are selected because they have actively accessed multiple banking products and services. They are commonly known as the “early adaptor, trailblazers, and movers” in digital finances.

These woman ambassadors will mentor the members of cooperatives to access the digital financial services and products offered through Laku Pandai agents. The weekly meetings of cooperative groups provide an excellent forum to exchange information and knowledge.

Women Digital Ambassador (WDAs) can become the torchbearers to accelerate women’s financial inclusion

Women’s cooperatives integrated with Laku Pandai services and supported by the WDAs are expected to give deeper, broader, and measurable impacts on collective initiatives that engage women in the digital economy, especially in rural areas.

Through these initiatives, MSC expects to support the vision of financial inclusion for Indonesian women outlined in the National Strategy of Financial Inclusion—Women (SNKI-P). SNKI-P intends to achieve 90% financial inclusion by 2024. The initiatives need support from financial service providers, including bank and nonbank institutions, to upskill Laku Pandai agents in operation and customer services to create quality agents.

However, financial inclusion is not the endgame. Instead, it is a vehicle to accomplish objectives like gender equality, women’s economic empowerment, leadership, and poverty alleviation.

Over the next few months, MSC and PEKKA will develop a training module for WDAs and an operating model for the new “cooperative Laku Pandai agents.” MSC has also partnered with financial service providers to ensure that these banking agents receive sufficient support to succeed. Tune in as we publish more updates.

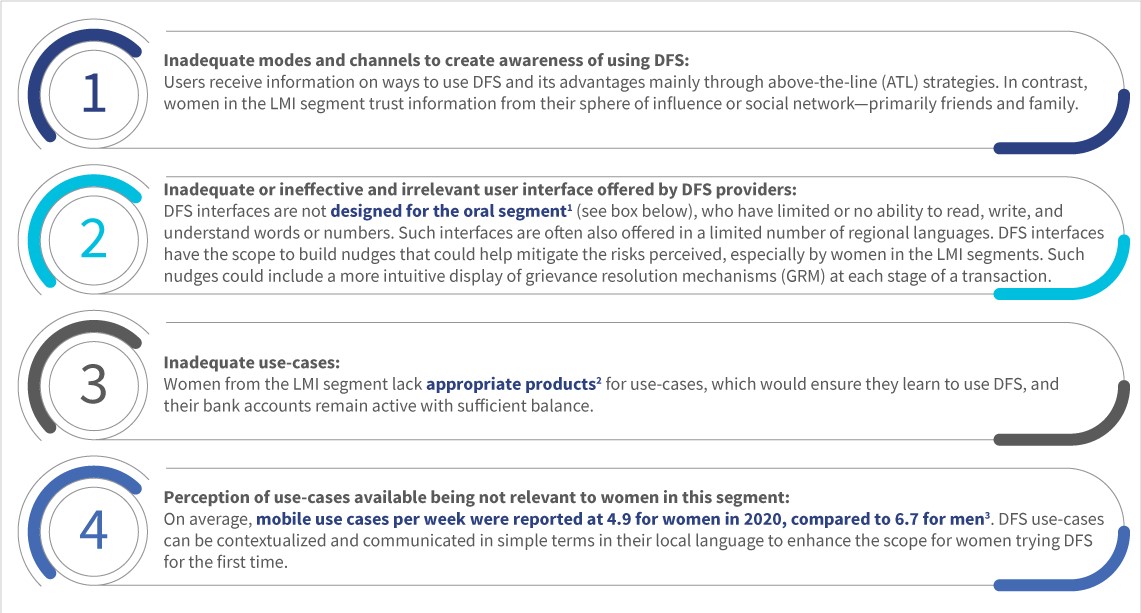

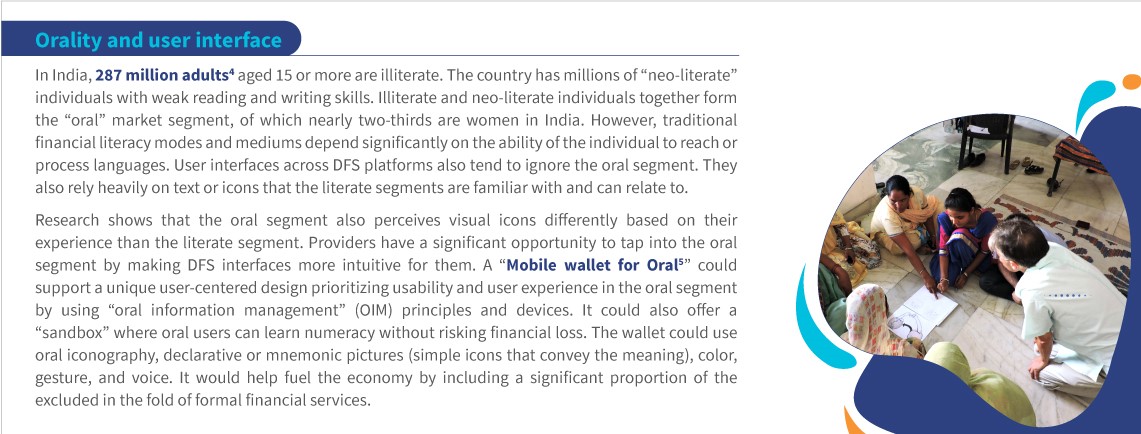

Financial inclusion for women in India still has a long way to go. While more women appear to be financially included, the use of these accounts remains limited across the country, especially among low- and moderate-income (LMI) women. Women’s ownership of bank accounts has improved over the years. The increase is primarily due to the

Financial inclusion for women in India still has a long way to go. While more women appear to be financially included, the use of these accounts remains limited across the country, especially among low- and moderate-income (LMI) women. Women’s ownership of bank accounts has improved over the years. The increase is primarily due to the