https://www.microsave.net/helix-institute/Recently, a team of qualitative researchers interviewed sixty mobile money agents and users in Kenya and Uganda to understand the drivers of important behaviours like non-compliance. The findings were intriguing since it was clear that the driver of agents breaking some rules and regulations was their ambition to provide excellent customer service and thus increase the likelihood of repeat business, and therefore the reputation of the provider’s brand they represent. From this perspective it is quite ironic that they might receive heavy penalties from the providers or regulators themselves for this.

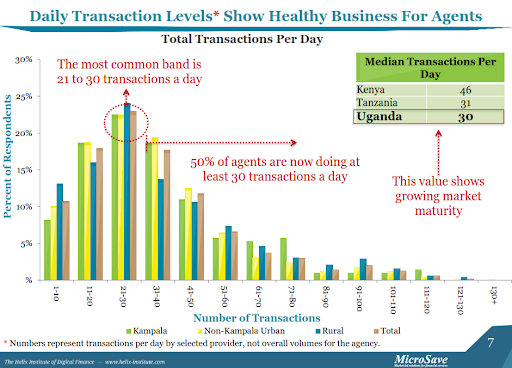

The ANA Uganda country report shows significant variations in transaction levels between agents, across urban and rural settings. There are various factors that affect number of transactions at the agent point, the quality of customer service being amongst the most paramount. Good agents consistently strive to offer a trustworthy and convenient service and with competing agents usually located all around them, they have to be clever about using all the tools and relationships they have available. This enables them to grow a loyal customer base and guarantees demand for their services, however, as can been seen from the three examples below sometime they prefer to work outside the system to do so.

The ANA Uganda country report shows significant variations in transaction levels between agents, across urban and rural settings. There are various factors that affect number of transactions at the agent point, the quality of customer service being amongst the most paramount. Good agents consistently strive to offer a trustworthy and convenient service and with competing agents usually located all around them, they have to be clever about using all the tools and relationships they have available. This enables them to grow a loyal customer base and guarantees demand for their services, however, as can been seen from the three examples below sometime they prefer to work outside the system to do so.

Customers transacting without identification: Most of the agents interviewed do not enforce the regulation that requires customers to show their identity cards before a transaction can occur. Whilst one could argue that display of identity card is actually to the benefit of the agent as chances of being conned or defrauded are decreased, some of the agents said that many of the customers come to transact without identity cards and insisting on it will likely lead to loss of customers since there are plenty of agents willing to serve them without their identity cards. Helix Institute research in Uganda in 2013 further revealed that agents reported recognizing a median of 50% of customers they served as repeat customers. At some point it is just embarrassing to ask people you know to prove who they are, and agents seem to favour serving customers more informally to encourage their return business.

Direct Deposits: In this case, the agent receives instructions from the customer on what amount to send and to where, and the agent goes ahead and sends it directly from his phone to the recipient. Mary, a customer in Uganda, requests her agent to send money to an intended recipient on her behalf, and she later pays him when she gets cash. The convenience of being able to send money on credit, and with some customers, even being able to call their agent to have it sent and then go in and pay later is incredibly convenient.

Such cases are not just common in Uganda. An M-PESA customer in Kenya mentioned that her agent allows her to conduct transactions even when she is not physically present at the outlet. Most telecoms try to discourage this behaviour as it means they have to pay the agent a commission on the deposit, yet do not earn revenue on the P2P transfer, as it is circumvented by having the agent make the transfer themselves. Telecoms might think about how to price these activities into the system as opposed to banning the increased levels of customer service their agents are offering.

Customers not signing the record book: When customers make a transaction, the agent is supposed to record it manually in a logbook and the customer is supposed to sign to acknowledge the details of the transaction, however, not all agents follow this practice. Agents say some of the customers are reluctant to do this as they are always in a hurry to leave and do not want to be bothered while others cannot write (almost 30% of Ugandan adults are illiterate). Again, the agents argue that insisting that the clients sign in the record book, makes them less competitive relative to the multitude of competitors in the market who are not strictly enforcing this regulation.

Why are these insights important?

Since better customer service, and thus increased usage, is in the interest of providers, agents and customers, it is time to be creative and examine ways that the customer needs that are driving these behaviours can be met within the bounds of mobile money system. Providers and regulators need to also understand that as the market matures, it becomes more congested with agents and different providers selling their services, and these types of behaviours will become both more common and also harder to control.

It seems time for a rethink in the name of customer service in advanced markets like Kenya and Uganda. IDs are not required at the ATM, can just a PIN be good enough at an agent as well? Or can agent interfaces be updated so that when they input a customer’s number their ID pops-up in the screen for verification (tablets or smartphones would be needed)? Can the profile then be saved, so the customer can then be “fast-tracked” at that outlet in the future? Can a system be developed in general that allows agents to treat their preferred customers as such? The Helix Institute research in 2013 in Kenya and Uganda showed that 35% and 52% of agents respectively in each country had been operating for a year or less. This means there is only more competition to come, and providers who focus on these issues, and give their good agents an edge with customer service, will certainly see results in their bottom-lines.