Blog

Use of electronic vouchers for distribution of relief Part 2

In our previous blog, we discussed why humanitarian organizations and governments the world over use e-vouchers to distribute relief. We presented the challenges in the disbursement of cash and physical goods and outlined the benefits e-vouchers present to recipients, humanitarian organizations, governments, and the ecosystem. We highlighted examples of programs that have implemented e-vouchers successfully.

In this blog, we take a close look at the implementation of e-vouchers in Kenya. We assess the roles of key stakeholders in the ecosystem, understand the challenges they face, and reflect upon the lessons learned so far.

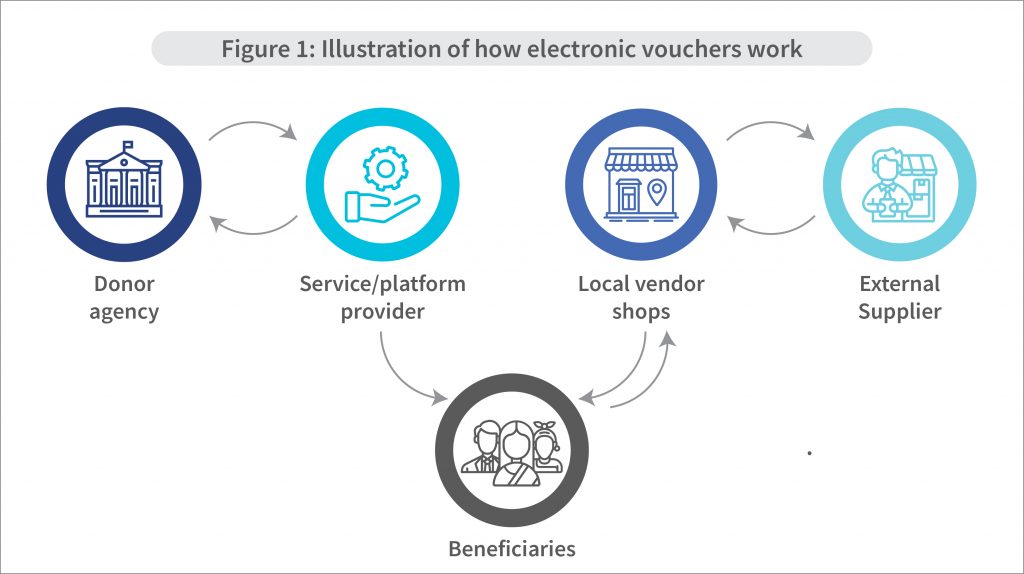

The implementation of an e-voucher system requires various actors within the ecosystem. It entails coordination among stakeholders comprising humanitarian organizations and governments, the platform or service provider, local vendors, external suppliers, and beneficiaries.

The various actors within the ecosystem play different roles, as follows:

Humanitarian organizations and governments

- Provide funds for social benefits transfers

- Collect beneficiary details, such as demographics, GPS coordinates, levels of food insecurity, and criteria for other programs

- Make bulk payments using Real Time Gross Settlement to the payment service provider(s)

- Share the e-voucher with the beneficiaries using an SMS to the mobile phone number nominated by the beneficiary; the message also provides details on how and where the beneficiaries may redeem the voucher

The payment service provider(s)

- Generate e-vouchers and issue them to humanitarian organizations and governments to distribute them to the beneficiaries

- Issue a USSD code for the beneficiaries; beneficiaries dial and follow the prompts on the USSD platform to pay for the specified goods at a merchant outlet

The beneficiaries

- Redeem the electronic vouchers in exchange for goods predefined by the donor agency

The local vendor

- Receive electronic value as a transfer of float to their e-money wallet

- Use the electronic float to replenish their supplies by paying external suppliers

Figure 2: AN example of an electronic voucher redeemable at a specified merchant outlet in Kenya

Challenges of using electronic vouchers

Limited choice of shops to redeem vouchers

The humanitarian organizations and governments may predefine the shops where the e-vouchers can be redeemed. In some instances, remote areas may lack enough shops, which may mean that beneficiaries have to travel far to redeem the e-vouchers for predefined goods. Due to reduced competition, the shops may increase the prices of goods, sell substandard quality items, or charge beneficiaries for products they have not purchased.

Low levels of digital capability

Low levels of digital capability undermine the use of mobile services, which impedes the usage of e-vouchers.

Infrastructure challenges

Challenges related to infrastructure, such as inadequate mobile network connectivity hinder the ability of beneficiaries to use e-vouchers and also their ability to join assistance programs. Programs incur high costs when setting up the e-voucher system.

Inadequate access to technological tools, such as mobile phones

According to World Bank data, Kenya has a high mobile cellular subscription of 96.32 per 100 people compared to the average in Sub-Saharan Africa of 82. Beneficiaries of social benefit programs, and particularly women have lower mobile phone ownership, live in areas with poor connectivity, and have insufficient access to electricity.

Preference for cash by external suppliers

The residents receive the e-vouchers and exchange the value for goods or services at local stores. The vendors subsequently redeem the electronic value to replenish their stock of goods or services. The lack of a digital economy may pose a challenge in remote areas since the suppliers may not accept electronic value as they often prefer cash value.

Risk of diversion of benefits

The e-vouchers program works well if the beneficiaries’ data is accurate and reliable. The point of data collection has a vulnerability—local actors may add beneficiaries who are not whom the social assistance programs target. The risk of poor targeting methods and identification reduces the impact of the interventions.

Increased costs of maintaining beneficiary database

Maintaining beneficiary databases is always challenging. This is because of the need to clean up the data regularly to take account of movements of beneficiaries, deaths, and other circumstances that may change the beneficiary’s status.

How can stakeholders address the challenges?

- Increased investment in digital capability: To increase the adoption of e-vouchers, stakeholders in the relief aid sector need to work together to promote the digital capability to enable beneficiaries to accept and use e-vouchers. Training on digital capability at the village level with the help of community-level influencers or agents can be one effective way of imparting knowledge on the use of e-vouchers and other digital financial products.

- Increased investment by county and national governments: The governments at the national and county levels need to increase investments to encourage the growth of local retail shops and allow beneficiaries of electronic vouchers to exchange their vouchers for goods and services. In Kenya, trade and industry are largely a function devolved to the county governments. County governments need to employ concerted efforts to facilitate trade in the counties to enable locals to open and operate retail shops. This can be done by creating enabling policies and a conducive environment for retail businesses to operate. For example, the Kakamega County government has budgeted for setting up modern markets in every sub-county to facilitate trade by constructing lockable stalls, providing lighting, 24-hour security and access to low-interest loans, and capacity building to enable them to utilize the funds effectively.

- Create incentives for mobile network operators: Donor organizations and government actors need to incentivize mobile network operators to invest in infrastructure in rural areas to enable the connectivity that is critical to support e-vouchers. Ultimately, this will be a commercial decision and will drive companies to deploy new technology, such as nano satellites. The question is not if, but when—and how policymakers can encourage and accelerate this coverage.

- Create innovative models to increase the ownership of technological tools: Lack of access to technological tools, such as mobile phones, especially among women reduces the ability of some beneficiaries to receive the e-vouchers. Donor organizations and government actors must create innovative models and partnerships to enable financing to enable low-income beneficiaries to acquire mobile devices and pay for them according to their income patterns. Models, such as pay as you go (PAYGO) enable beneficiaries to acquire devices and pay for them in staggered payments of daily or weekly installments according to the ability of the client. Besides, in some regions, special attention will be required to ensure that female beneficiaries continue to own and use mobiles.

- Increased awareness of campaigns on the use of digital payments: Stakeholders, such as regulators, policymakers, and financial service providers need to work together to increase the effectiveness of e-vouchers and the use of digital payments. This would also increase awareness on the benefits of digital payments to increase their acceptability. For example, the elimination of commissions on low-value transactions by providers in Kenya as part of the response to COVID-19 increased uptake and usage.

- Increase efficiency in data collection: Donor organizations and government actors need to increase efficiency through additional verification of beneficiaries to reduce the risk of targeting the wrong beneficiaries. While this may come at an additional cost to the donor organizations, it will ensure that the right beneficiaries receive the relief aid.

- Proper identification of beneficiaries: A robust selection mechanism is needed to ensure the right beneficiaries are targeted with social assistance. It should target only those who need social assistance and eliminate those who do not. For example, the use of stop-gap measures, such as mobile operator databases and social registries can identify new beneficiaries of social assistance to eliminate the bias in the selection of new beneficiaries.

- Automation of beneficiaries’ databases: Automated beneficiary databases need to be implemented to reduce monitoring and maintenance costs and manage the onboarding, payment, and exit processes of beneficiaries. This will enable donor organizations to cut down on the costs of maintaining the databases. Investing in a robust management information system to manage the onboarding, payments, grievances, and exit processes is one of how donor organizations can manage the costs of maintaining beneficiary databases.

Lessons learned

As the world gears up to the second wave and different strains of COVID-19, the low- and moderate-income populations will require support from humanitarian organizations and governments. According to research conducted by MSC, innovative delivery of targeted social assistance to low- and moderate-income people is critical to ensure their survival. Adherence to the mandated social distancing and preventive guidelines will provide a further impetus for digital financial services to support targeted social assistance efforts.

E-vouchers provide an opportunity for donor organizations and government actors to support individual beneficiaries and provide much-needed community development by supporting local economies. As an immediate response mechanism, e-vouchers allow beneficiaries to address their basic needs, facilitate improved preparedness and recovery, and overcome the loss of income and livelihoods among the most vulnerable.

However, e-vouchers require governments’ support and political goodwill to succeed. As governments are the major distributors of relief to vulnerable populations, its buy-in helps encourage digital financial services and e-vouchers to distribute social assistance.

E-vouchers present several benefits, such as enhanced reach, better accountability, and robust monitoring. Humanitarian organizations, governments, and the private sector have a strong case to use e-vouchers for disbursements. The conditional use of funds allows for their traceability. Thus, governments may use e-vouchers to provide bursaries to students in public government schools and bolster women’s health programs, such as the Linda Mama program.

Capacity-building efforts by payment service providers for beneficiaries and other stakeholders, such as government employees, retail merchants, and service providers are necessary to promote stakeholder buy-in, encourage acceptance, and enhance ease of use for beneficiaries.

When done right and done well, digital voucher assistance places people at the center of any humanitarian response, ensuring that those excluded from digital and financial opportunities can effectively access, use, and make their own life-defining decisions for their families.

Use of electronic vouchers to distribute relief part 1

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, residents of Kibera, the largest slum of Sub-Saharan Africa, gathered at a district office to collect food donated by former Prime Minister Raila Odinga. These donations were made to cushion the residents from hunger amid the pandemic. The situation got out of hand and a brief stampede ensued, which led to the death of at least two people and injuries to several others.

Social distancing became the new normal during the pandemic. In the pre-COVID-19 era, humanitarian organizations, such as the World Food Programme (WFP) used to deliver food aid physically. Since the outbreak, these organizations have struggled to distribute relief to the extremely poor as they fear contracting or spreading the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

In light of the causalities caused by the poorly organized and chaotic food donation drive in Kibera, the Government of Kenya banned the public distribution of food and non-food donations within communities across the country. The government envisages that this ban will curb such incidents in the future. To avoid the recurrence of such incidents, humanitarian organizations must find new ways to distribute relief.

Digital technologies have been transforming the way we respond to emergencies. An example of such an innovation is SurePay. Launched by M-Pesa in Kenya, SurePay is a service that facilitates humanitarian organizations to distribute relief to specified recipients using electronic vouchers. Through e-vouchers, humanitarian organizations can impose restrictions on funds for specific uses and to specific cash-out points. During crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, humanitarian organizations can use e-vouchers to distribute social assistance to those affected adversely.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the health, social, and economic situation of communities across the world.

Reeling from significant income losses, low- and moderate-income populations need support from governments and humanitarian organizations.

Reeling from significant income losses, low- and moderate-income populations need support from governments and humanitarian organizations.

Humanitarian organizations have been providing relief to vulnerable groups for quite a while through the physical distribution of food and cash. However, these organizations have faced several challenges, some of which are as follows:

- “Leakages” in benefit transfer programs by intermediaries

- Diversion of benefits to unintended purposes by the beneficiaries

- High cost of logistics involved in handling cash and distributing it physically among the recipients

- Risk of sidelining women, since male members of the household tend to collect cash on their behalf and sometimes divert these funds to unintended

The World Food Programme (WFP) introduced the e-voucher system in Kenya in 2015 to disburse funds to beneficiaries. It implemented the e-voucher system in five counties to strengthen its cash-based response. Through e-vouchers, WFP ensures that beneficiaries use cash to pay for food from designated stores. These vouchers enable WFP to trace the entire value chain from disbursement to the expenditure of funds. A back-end functionality provides humanitarian organizations with reports that show the utilization of funds in terms of the amount, balance, and stores where beneficiaries used the funds. WFP, in partnership with Mastercard, has now been implementing similar e-voucher programs in 25 countries.

In other markets, such as Nigeria, humanitarian organizations use e-vouchers to distribute relief to internally displaced people and vulnerable host communities in conflict-prone areas. Catholic Relief Services (CRS) has also been providing food assistance to conflict-affected states in Nigeria. Initially, CRS disbursed cash to beneficiaries. However, due to challenges around logistics and security of funds for cash disbursement, CRS switched to e-vouchers.

Why should humanitarian organizations and governments use e-vouchers?

Why should humanitarian organizations and governments use e-vouchers?

Humanitarian organizations and governments can use e-vouchers to enhance cost-effective reach for beneficiaries at the last mile. This saves logistical costs associated with the delivery of food items or cash to beneficiaries. Humanitarian organizations and governments can remotely process and share e-vouchers with the nominated phone numbers of the beneficiaries.

E-vouchers can also help widen the reach of both humanitarian organizations and governments through nominated agents or local administrators, such as chiefs and sub-chiefs, who can map and collect mobile phone details of beneficiaries. The data collected can help create a database of beneficiaries for relief distribution. Agents and local administrators can identify and register beneficiaries from remote areas and pastoralist communities, who often migrate from one place to another.

Some other benefits of e-vouchers are listed below:

- Reduced administrative costs: E-vouchers are cheaper to use due to the lower cost of distribution logistics. Humanitarian organizations and governments can repurpose these savings and reallocate more resources to relief efforts.

- Economic growth of the local area: Beneficiaries redeem vouchers at designated local shops to get the food items. This increases the circulation of cash, which results in the economic growth of the local area. Hence, e-vouchers have a multiplier effect on the local economy.

- Better governance: E-vouchers can help enhance transparency and accountability, and reduce chances of misappropriation before the funds reach the target beneficiaries. This enables humanitarian organizations and governments to ensure that the intended beneficiaries receive the vouchers and utilize the funds appropriately.

- Enhanced data-backed monitoring of disbursements: To administer e-vouchers, humanitarian organizations and governments create data sets of beneficiaries. Such databases have multiple use-cases, such as determining consumption preferences of beneficiaries within different localities. Humanitarian organizations and governments can also develop a customized portal to assess the use of funds by beneficiaries.

- Ability to restrict the use of e-vouchers to desired purposes: Humanitarian organizations and governments can enforce conditions on how and where beneficiaries can use the provided funds. By locking the redemption options to specific vendors, such as food stores, they can ensure that beneficiaries utilize the disbursed funds meaningfully.

E-vouchers offer several benefits to recipients, humanitarian organizations and governments, and the larger ecosystem.

In our next blog, we examine the implementation of e-vouchers comprehensively. We also assess the roles of key stakeholders in the ecosystem, understand the challenges they face, and reflect upon the lessons learned so far.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs): Senegal country report

MSMEs in Senegal contribute an estimated 40% to the GDP and are a major source of employment. Nine out of 10 workers are engaged in informal employment, with 97% of companies in the informal sector.

Still reeling from the effects of the pandemic, MSMEs need targeted support to build resilience, transform into formal entities, and continue to contribute to the local economy.

This study provides a detailed country-level view of the impact of COVID-19 on MSMEs and their coping strategies. It further provides recommendations for policymakers and financial service providers to support MSMEs in Senegal.

Click here to read the report in French.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH)

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in April, 2020, the Government of Indonesia (GoI) took multiple measures to support the ailing economy. Its critical policy support measures involved the expansion of Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH), the flagship conditional cash transfer program implemented by the Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSA) to include new beneficiaries. GoI also increased the entitlement of beneficiaries under its social protection programs. This report is based on the study MSC conducted in coordination with MoSA to understand the impact of the pandemic on the implementation of PKH. It also highlights how beneficiaries coped with economic hardships, accessed their PKH funds, met their commitments under PKH, and accessed health facilities as the pandemic raged on.