Blog

The digital journey of Shakti Foundation for Disadvantaged Women: a lesson for progressive MFIs in Bangladesh

About four years ago, Shakti Foundation for Disadvantaged Women, our partner in Bangladesh, faced multiple cases of misappropriations related to its voluntary savings product. As a result, the senior management team of Shakti decided to withdraw it. They realized the need to strengthen internal controls before offering voluntary savings products that create unpredictable flows of cash. However, the management was unclear and apprehensive about how to offer customer-centric products while managing the associated risks.

This case study charts how Shakti Foundation responded to these challenges through the conceptualization and implementation of appropriate technological interventions. It lists the interventions Shakti undertook, the critical factors behind their success, and the impact on Shakti and its customers.

The case study was developed as part of the Digital Microfinance Project funded by the MetLife Foundation. The project supports select microfinance institutions in Bangladesh to provide digital financial services, especially for savings, to their customers

Digital initiatives by Shakti Foundation for Disadvantaged Women

Savings, especially for low-income segments of the population, have been the Achilles heel of financial inclusion. The key challenge for Shakti Foundation for Disadvantaged Women, a microfinance institution in Bangladesh, was to offer savings products sustainably and at scale.

This case study charts the journey of Shakti’s women clients toward the adoption of voluntary savings products that ride on digital channels. It highlights the needs and aspirations of women customers and the behavioral biases and influences that determine the adoption of the savings product. Based on the identified behaviors, the case study also lists a set of design principles to develop a digitally-enabled savings product for low-income customer segments.

The case study was developed as part of the Digital Microfinance Project funded by the MetLife Foundation. The project supports select microfinance institutions in Bangladesh to provide digital financial services, especially for savings, to their customers.

Six aspects financial institutions must consider if they wish to serve young people

In the previous blog, we looked at why financial institutions should focus on youth. We examined the financial needs of the youth, the constraints at the demand and supply sides, the perceptions and reality of youth on financial services, and the business case for financial institutions to focus on youth. From experience, we know that many financial service providers (FSPs) wish to serve youth but lack appropriate products and services that suit their needs. In this blog, we highlight prominent aspects that financial institutions need to focus on as they design and deliver financial services to youth.

FSPs must consider the following six aspects if they wish to serve youth profitably and successfully:

- The youth are not a homogeneous group. We often hear FSPs say that they want to design products that will “generally” appeal to the youth. This risks lumping youth under one segment and one category. Young people who practice agriculture, for instance, do not have the same needs as those who operate retail shops. Those involved in agriculture need loan disbursement, repayments, and savings mobilization to be structured as per the agricultural cycle. Meanwhile, youth in retail businesses have different needs and demands. Product development, therefore, should be targeted according to business activity, geography, and ability to provide collaterals.

- FSPs need to understand whether regulation allows youth to access financial services and if not, what alternatives they can use. In Uganda, for example, anyone under the age of 18 are not allowed to open up a bank account. FSPs need to think creatively to find alternatives to formal identification and guarantee requirements. Some FSPs have resolved this challenge in KYC by requesting those younger than 18 years to come along with a trusted guardian who submits their KYC and operates the account jointly with them until they turn 18.

- The youth lack collateral. Most young people are either students or have just started work or a relatively young enterprise. Therefore, they do not have the usual collateral that FSPs require, such as land title and car logbook. They, however, might be able to provide collateral in the form of chattels, which may include business or household items. For others who lack collateral, group members can provide a guarantee to access the loans. FSPs should be flexible to serve the youth and consider starting them off with small amounts and gradually increasing these amounts over time based on their performance.

- FSPs need a multi-pronged strategy for risk management. Some FSPs prefer to use guarantees to manage the risks or use social funds and crowdfunding. In this case, when the youth fail to repay their loans or some of the transaction charges they incur, they have a fund in place to fall back to. For example,

- Some FSPs in Africa have used guarantee funds to cater to the risks that farmers encounter. Such guarantee funds can also be considered in youth financing. The Ugandan government through the Agriculture Credit Facility provides interest-free loans to selected financial institutions to on-lend to small- and medium-sized value chain actors. This enables the actors to access cheaper credit. The FSPs on the other hand can obtain a 50% reimbursement on the loans after they lend to the value chain actors.

- The Nike Foundation covered transaction costs for adolescent girls who wanted to open up accounts at two FSPs in Uganda for two years. This offered a twofold advantage. Not only did this cover the FSP’s operational costs on the accounts, but also allowed the girls to grow their savings and appreciate the value of saving in a safe space.

- FSPs require to show buy-in and commitment from their top governance and executives toward serving the youth. This will involve training staff on how to serve youth with respect and dignity. They would also need performance metrics and reporting formats to monitor uptake and follow-up of the youth portfolio.

- Some youth need non-financial services to enable them to gain further knowledge and skills and run their enterprises professionally and efficiently. The FSPs can offer these non-financial services if they collaborate with a third party. For example, a few years ago, the Population Council partnered with Finance Trust Bank and FINCA—both located in Uganda—to provide financial education to adolescent girls who opened accounts at these institutions. Opportunity Bank Uganda has also engaged providers like Teach a Man to Fish to equip customers with business management skills including record keeping, customer care skills, digital and financial literacy, and networking. To bring all these opportunities and issues together, FSPs must use a systematic approach to product development for youth. MSC uses the 8Ps Framework to do this, as outlined below.

In conclusion, FSPs should design products and services that reflect the diversity of youth. Products should vary by demographic parameters, such as age, education, and geography or life cycle stage and economic occupations, just as with older clients. The major product differences lie in marketing, delivery mechanisms, and in the accompanying non-financial services. Taken together, these specially designed products will be critical for building a young person’s capacity to save, manage their money, and generate income.

Why should financial institutions focus on youth?

The median age of Africa’s population is 19.5 years. In 2019. almost 60% of the population of Africa was under the age of 25, making it the world’s youngest continent. For this blog, we use the definition provided by the African Youth Charter for youth as any individual between 15-35 years of age.

The median age of Africa’s population is 19.5 years. In 2019. almost 60% of the population of Africa was under the age of 25, making it the world’s youngest continent. For this blog, we use the definition provided by the African Youth Charter for youth as any individual between 15-35 years of age.

Like other segments, young Africans need financial services. As per estimates by the ILO, of the 38.1% estimated total working poor in sub-Saharan Africa, young people account for 23.5%. Even though the unemployment rate of the youth in Africa is quite high, young poor workers and even the unemployed can benefit from financial services. However, 80% of youth remain financially excluded. According to the ILO and the MasterCard Foundation, Sub-Saharan Africa has the second-lowest level of formal account holders after the Middle-East and North Africa (MENA) region. Financial service providers (FSPs) struggle to serve youth profitably and sustainably because they make small, infrequent savings and have a high-risk credit profile.

Only those FSPs that are socially oriented and interested in the economic empowerment of youth or choose to focus on youth as a niche market make the effort to design and deliver youth-focused financial services. However, both youth and FSPs can benefit from each other. This is because FSPs can create a business case to serve young people and reduce costs by encouraging account usage, cross-selling products, and using technology-driven models.

Financial needs of youth

To successfully serve young people, FSPs should make a concerted effort to understand youth as a unique segment. MSC’s experience highlights that youth have personal and business-related needs. Personal needs primarily relate to lifecycle events, such as education and marriage. On the other hand, business-related needs include starting and running a business, business expansion, or capital assets acquisition, or all three. Like other segments, youth often require lump sums to meet their business-related needs since these cause the greatest financial pressure. In most cases, the youth resort to either savings or credit to generate lump sums.

Since formal financial services are not tailored to their needs, most young people rely on coping mechanisms. These include borrowing from parents or relatives and informal groups, such as Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLAs). However, these mechanisms are limited in their nature and may not provide adequate lump sums that the youth need to raise. According to a MasterCard Foundation report, the needs for financial services become more complex as the youth become older and get more income streams. Thus, the need for FSPs to be adequately positioned to meet these needs through the years.

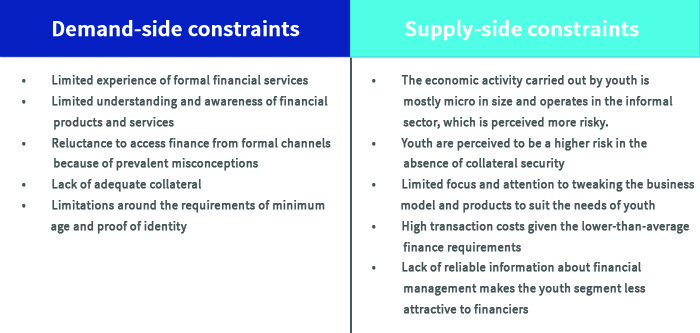

Demand- and supply-side constraints

Although the needs for the financial services for youth are not radically different from the needs of other segments, the level of financial exclusion is higher due to a combination of factors. The key constraints on both demand and supply sides that are specific to the ability of young people to access finance are as follows:

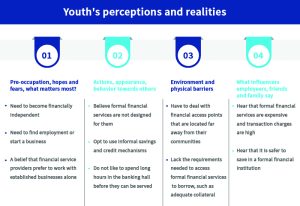

Figure 1: Youth perceptions

The perceptions and reality of youth

While the youth segment is by no means homogeneous, the perceptions and realities of young people differ significantly from other segments. The table below outlines the key differences.

Understanding these perceptions and realities enables the FSPs to serve the youth better. In the next section, we demonstrate through a business case on serving the youth by financial institutions.

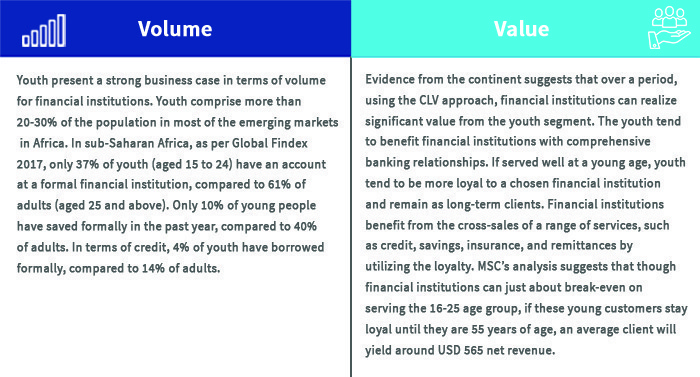

The business case for financial institutions to serve the youth

The business case for financial institutions to expand financial services to the youth is based on a combination of factors related to volume and value.

Most of the sub-Saharan African markets currently lack any market leader in this space. This offers enormous potential for formal financial institutions to develop a brand as a financial partner for youth. An institution entering the youth segment will have a first-mover advantage.

In the next blog, we highlight how financial institutions may develop and deliver appropriate products and services that suit the needs of the youth.

Navigating the new normal: Can behavioral sciences help?

Introduction

The unabated increase of COVID-19 infections has forced India, like almost every other nation, to figure out the most effective way to deal and live with the virus. With about four months in lockdowns in place, COVID-19 has exhausted people both mentally and physically across the world. This is being called “pandemic fatigue” or “disaster fatigue.” It had led the public to move out of their homes as soon as lockdown restrictions are eased to resume their social and economic life. The government now faces a tough challenge as people emerge from their homes and travel to crowded markets and workplaces. Since June, 2020, when the government first lifted the lockdowns, India reported 2,270,655 new cases. As of August 14th, the country had 2,461,190 live cases.

MSC conducted a study in this context in April-May 2020, which offers some important insights. We learnt that the government was able to generate awareness: 85% of respondents had a fair idea of the fatality of the disease while more than 80% knew how contagious the disease is and how it spreads. However, the study also found that misconceptions and malpractices were prevalent. 15% of Indian respondents reported the use of locally available solutions to protect themselves from infection, including the use of anti-pneumonia drugs, neem tree (Azadirachta indica) leaves in oil, naphthalene balls placed around the house, saline nasal rinses, among other methods. The study showed that a similar situation prevailed across many countries. (Please see this dashboard for country-wise statistics).

Our study revealed that only 22% of Indian respondents practiced the use of facemasks and only 32% maintained personal and home hygiene. Misconceptions and malpractices are still prevalent. To address this holistically, a comprehensive digital Social Behavioural Change Communication (SBCC) campaign is essential to encourage appropriate behaviors.

An SBCC is in place, but more is needed

While the government is trying to optimize the provision of healthcare services, these efforts will be futile without the active involvement and contribution of the public. COVID-19 is here to stay for the near future and the world must adjust and learn to live accordingly. People need to maintain social distance, wear masks, and avoid unnecessary travel and gatherings, besides taking other necessary precautions.

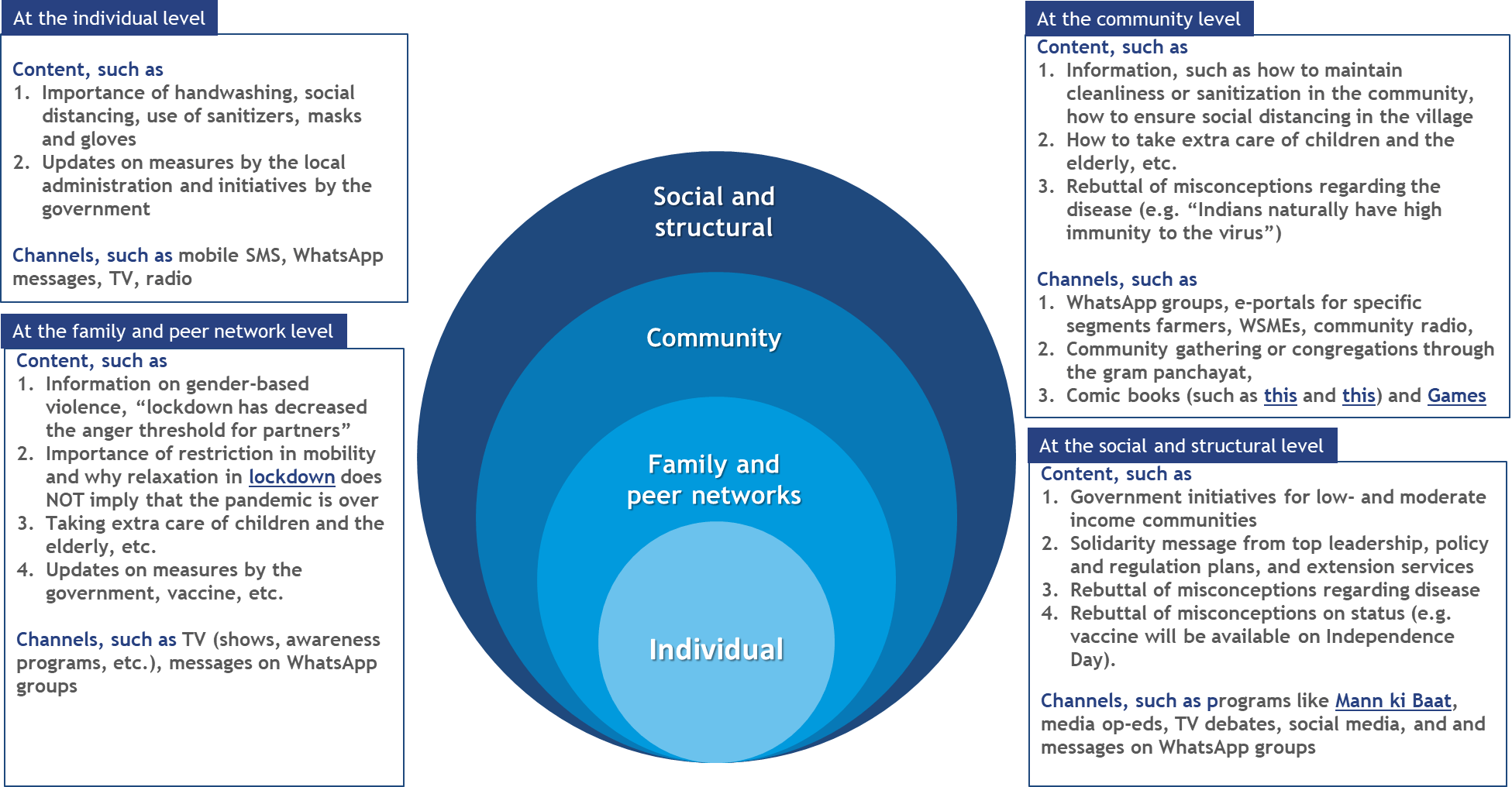

This adaptation needs to be consistent, especially in the face of pandemic fatigue. Strategic use of communication approaches can promote sustainable changes in knowledge, attitudes, norms, beliefs, and behaviors. Living with the COVID pandemic can be seen as a classic use-case for SBCC sciences. SBCC acknowledges four levels of influence that interact to affect people’s behaviors: individual, family or peer networks, community, and the social or structural environment.

In addition to various audio and visual aids to address the remaining knowledge gap, prevalent myths and misconceptions, and pandemic fatigue, the Indian government has been working on the lines of SBCC with interventions and campaigns. These include measures, such as replacing the pre-call ringtones of users with an advisory on COVID-19, launching national and state-level toll-free helpline numbers, and campaigns like #newnormal, #maskforce, among others. However, the current communication approach, which is generic, still lacks targeted and customized communications based on situational analysis.

We need an SBCC campaign that goes beyond the broader Information Education Communication (IEC)/ Behavioral Change Communication (BCC) to contextualize it as per the specific needs of different communities. Going forward, audience segmentation is needed to identify subgroups to deliver more tailored messaging for stronger connection and resonance. For instance, our study shows that the pandemic has different effects on different populations, such as men and women.

Our study revealed that women have poorer levels of knowledge around COVID-19 and subsequent behaviors as compared to men. Women are less likely (39%) to be aware of COVID symptoms than men (46%). Fewer women (59%) practice handwashing than males (74%). Across every sphere, from health to the economy, security to social protection, the impacts of COVID-19 are worse for women and girls simply because of their gender. Messaging must address these gender vulnerabilities as well as issues like differential access to financial resources, healthcare and nutrition, gender-based violence, responsibility-sharing, among others, especially in the times of disaster—like now. Similarly, we can customize the messages for other vulnerable groups like the differently-abled, the elderly, and tribal groups, among others.

A digital SBCC with a human touch

In this context, the government may take advantage of the improved mobile and internet penetration caused in the wake of the pandemic. Though India has been already tracing contacts through applications like Aarogya Setu, it is time to optimize the use of digital channels for behavioral change. India’s internet usage has climbed up by a margin of more than 50% since the lockdown in March, 2020—with 58% of MSC’s study respondents reporting that they spent more time on their phone. A recent study by IAMAI and Nielsen reports that rural India has 0.2 billion active internet users, which is 10% more than the number in urban areas.

While advocating the use of digital channels for behavioral change, we must highlight that the involvement of communities is essential. Although digital communication channels can be distributed more widely and targeted better, community engagement contextualizes the messaging and channels required for behavior change to meet the specific needs and situations of the community. The Government of India urged grassroots NGOs to partner with district administrations and contribute to the COVID-19 response efforts. Co-creating the campaign with those for whom it is being designed for improves outcomes significantly. Governments at center and states can rope in those who lost their jobs or have time because of reduced employment opportunities to create a new cadre for community engagement

Conclusion

The importance of communication has been emphasized in this SWOT analysis of the pandemic. Further, a NITI Aayog article mentions that the COVID-19 pandemic has “confronted [us] with a battle against untamed emotions.” It points out the role of emotional Intelligence in preserving our collective mental wellbeing in these times. The NITI Aayog has also developed a toolkit containing posters and videos, among other resources that aim at having behavioral shifts in the audience. The multiplicity of channels that digital tools offer makes it a potent way of inducing nudges. Examples of digital campaigning to tap into people’s behavior are not new to India. In the recent past, television shows have been used to give women a sense of empowerment. Videos on health and nutrition to promote good reproductive health have also seen use.

As COVID-19 tightens its grip in non-metro cities and rural areas, there is an urgent need to develop or enhance an ecosystem to implement SBCC. Given the current situation, and the challenges we foresee due to changing behaviors, SBCC’s power to explain things and its capacity to innovate contextual solutions will be key to drive the required behavioral changes. India can and should make full use of the available resources of human capital and digital penetration to co-create a campaign of positive behavioral change, which would give more teeth to the battle against the pandemic.