These short articles are based on years of on-the-ground research and technical assistance dedicated to developing sound business models and operations to underpin profitable approaches to serving the mass market, thus advancing financial inclusion.

Blog

Role of Bank Mitrs in Direct Benefit Transfer Ecosystem: Are Banks and Government Ignoring Their Brand Ambassadors?

The direct benefit transfer (DBT) programme is an important and far-reaching initiative of the Government of India. The successful rollout of DBTL (DBT for subsidy transfer of domestic LPG) could save Rs. 7,700 crore (USD 1.167 billion) for the government. This is about 38% of subsidy budget of Rs. 20,000 crore (USD 3.01 billion) for LPG.

The direct benefit transfer (DBT) programme is an important and far-reaching initiative of the Government of India. The successful rollout of DBTL (DBT for subsidy transfer of domestic LPG) could save Rs. 7,700 crore (USD 1.167 billion) for the government. This is about 38% of subsidy budget of Rs. 20,000 crore (USD 3.01 billion) for LPG.

Similarly, if we assume an approximate saving of 38% through DBT in four schemes (MNREGA,[1] NSAP,[2]Fertiliser Subsidy Scheme[3]and PDS[4]) the government could save up to Rs.100,000 crore (USD 15.15 billion) out of the total subsidy budget of Rs. 270,000 crore (USD 40.09 billion). However, the success of these schemes will not depend only on the design of the programme and budgets allocated – the entire ecosystem must work properly for DBT to succeed.

While technology is the backbone of DBT, the importance of the role of front-end, last mile transaction points cannot be underestimated. By design, DBT schemes target the most vulnerable sections of the population (with the exception of DBTL, in which almost all sections of the population are covered). But this segment struggles to access banks for a variety of reasons: sometimes because they live in remote areas, far from bank branches; and often because they lack the knowledge and confidence to approach a bank. Additionally, they are not conversant with the banking system, and even if they are provided with access to the banking system, they depend on someone to conduct transactions for them. In this context, a robust agent or Bank Mitr (BM) network is the crucial link which can either make or break the implementation of the government’s flagship DBT programme.

Recent months have seen the re-emergence of a focus on the importance of this channel. The Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) scheme, that has helped open more than 180 million bank accounts in less than a year, has very clear emphasis on BMs.

What ails the Bank Mitr network?

The low number of transaction-ready Bank Mitrs has always been a point of concern for regulators and the government alike. In 2012, MicroSave provided technical inputs to a national survey on BMs by CGAP-CAB which suggest that BM availability was in the range of 57―78%. Lack of adequate remuneration for BMs was primarily responsible for their discontinuation.

In order to tackle this challenge, the PMJDY vision document mandates a minimum payment Rs. 5,000 (USD 75.75 per month) to BMs; however, an assessment recently conducted by MicroSave highlighted that BMs actually receive an average of Rs. 3,951 (USD 59.86).

However, low compensation is not the only issue, or even the only financial challenge that BMs face. There is a multitude of issues that can be classified in two categories.

1. Financial issues

a. No support for capital expenditures. There is no incentive for banks to support BMs’ expenses especially on technology, infrastructure, the branding of outlets and other capital items. As a result, BMs try to minimise their fixed cost on furniture and fixtures, computer/communication equipment, marketing, and even liquidity management (deposit in the settlement account, and cash in hand). The ANA report for India suggests that operating expenses for BMs are higher in India than other South Asian countries. The report highlights that rent, electricity and travel expenses for liquidity management constitute the bulk of the operational expenses for agents.

b. Delay in payment of commissions. Remuneration is not only small in absolute terms, but is also paid irregularly by banks/agent network managers (ANMs). The plight of BMs is often aggravated when the manager concerned (of the bank or the ANM) is transferred or retires. Most activities and processes are still person- rather than system-driven; so BMs have to start afresh each time a new manager takes charge. Furthermore, there is typically no intimation of pay out and no break-up or details about the business done by the BM for which payment is made. This leaves BMs unsure about their performance and/or what do they need to do to improve.

2. Non-financial issues

a. Lack of trust by customers. Many BMs are not recognised as bank agents. Many customers do not trust BMs because banks do not publicly promote the people or organisations working for them as trustworthy legitimate entities.

a. Lack of trust by customers. Many BMs are not recognised as bank agents. Many customers do not trust BMs because banks do not publicly promote the people or organisations working for them as trustworthy legitimate entities.

b. Lack of monitoring by banks and/or intermediaries. Though banks have designated officials to monitor the BMs, very often because of the branch’s routine work and limited staff, monitoring of BMs falls to the bottom of the priority list and is ignored.

c. Ad-hoc and incomplete training. The majority of BMs are trained on how to operate the transaction device and given a few tips on troubleshooting. International experience clearly shows that they should be trained on banking products relevant to the area/ local needs, and on soft skills such as customer service.

d. Absence of a proper grievance redressal mechanism. BMs also complain about the lack of a reliable support system through which their problems can be resolved. Resolution of most technical and non-technical issues takes a lot of time, and this both adversely affects their business and further erodes whatever little trust customers place in them.

e. Lack of awareness among the masses. People in rural areas do not have good information about financial products, government schemes, and allied benefits, which would have otherwise driven BMs’ business. BMs believe that banks and government departments should work to address the prevailing myths associated with agent banking through financial education campaigns.

What can the government, regulator and banks do?

1. Enforce the payment of minimum remuneration in a timely manner to BMs. This single measure will stabilise and encourage thousands of BMs across the country, providing a fillip to financial inclusion efforts of the government.

2. Banks and government agencies should develop and deliver clear customer communication for all key products and government schemes. BMs can then sell these to their customers.

3. Develop and deliver standardised and engaging training programmes that include relevant details about the financial products as well as soft skills, such as dealing with customers. This will both boost the confidence of BMs and allow them to act as real financial intermediaries, rather than just being another transaction point.

4. Our experience in field of BMs’ remuneration tells us that the expectation of remuneration is a function of capital expenditure that BMs make. Currently, individual BMs have to make this expenditure on their own, with no support from the banks that appoint them. If RBI includes loans extended by banks to BMs for capital expenditure eligible as part of Priority Sector Lending (PSL) requirements, it will moderate BMs’ expectations vis-à-vis remuneration and help banks meet their PSL targets.

5. Banks should recognise, promote and market the BMs working for them to generate recognition of, and trust in, the channel.

6. Put in place a comprehensive grievance redress mechanism to ensure adequate (technical or non-technical) support for BMs. Regulatory audits should audit the banks’ grievance redressal systems when reviewing BM channel.

Trusted, committed and liquid Bank Mitrs can (and indeed must) play a much bigger role if the government’s vision for financial inclusion is to succeed. This blog highlights the key challenges and opportunities to address them. The recommendations are not high-cost in nature, and, if implemented, could transform the BM network from an often moribund/dormant channel into a vibrant and profitable one.

[1]MNREGA is the largest livelihood security programme in India, guaranteeing 100 days of wage-employment to rural households whose members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.

[2] NSAP is a programme that has introduced a National Policy for Social Assistance for the poor and aims at ensuring minimum national standard for social assistance in addition to the benefits that states are currently providing or might provide in future.

[3] Fertiliser Subsidy Scheme is a programme in which the difference between the cost of production of fertiliser and the selling price/MRP is paid as subsidy/concession to the manufacturer.

[4] PDS in the country facilitates the supply of food grains and distribution of essential commodities to a large number of poor people through a network of Fair Price Shops at a subsidised price on a recurring basis.

Competition in the Kenyan Digital Finance Market: Digital Deposits (Part 3 of 3)

This is the third blog in a three part series, which compares digital financial service offerings in Kenya. The first blogfocused on mobile money services, the second one analysed digital credit and this one analyses digital deposits.

This is the third blog in a three part series, which compares digital financial service offerings in Kenya. The first blogfocused on mobile money services, the second one analysed digital credit and this one analyses digital deposits.

Digital deposit accounts are a controversial topic in digital finance. Many analysts note that mobile money providers cannot offer interest on the balance held in a mobile wallet, and that could be a deterrent to greater usage. However, for many Kenyan adults, savings rates are not high enough to make this a salient issue.

Deposit rates in Kenya are consistently below inflation rates, which were 6.9% in 2014, meaning they do not make money for the depositors; they simply help the depositors lose less than if they kept their money in cash or a mobile wallet. That is not the most alluring of value propositions, and the earnings on small account balances of a few hundred shillings (a few dollars) do not add up to much. Looking at deposit rates, M-Benki and M-Shwari provide the best returns, but it is really other features like reliability, flexibility, ease of access and the fact that savings contribute to credit scores that mass market customers generally value most highly.

.jpg)

The most interesting deposit account attributes are not their interest rates but the features they offer that really help people to manage their money. The attached credit features (analysed in the last blog) certainly drive usage, and some products also offer associated insurance cover. M-Shwari and the KCB M-PESA Account also launched a “Lock” feature (fixed deposits).

Furthermore, the KCB M-PESA Account launched an option to save for a specific target, which Equitel now offers as well. Equitel offers the additional feature of being able to send money to future dates. While we do not have usage figures for these different features, these are the factors we expect to differentiate the market most. Given the complexity of the financial management techniques required by mass market customers, we expect these features will go through many changes before they are actively used by the majority of people.

The low minimum balances all products share are excellent, and the absence of maximum account limits for M-Shwari and Equitel are sure to be popular with salaried workers and businesses. However, the maximum limit of one million KSH (US$ 10,000) in the KCB M-PESA Account is probably high enough for most Kenyans. The lower ceilings for Equity HapoHapo and the KCB M-Benki account might limit usage for middle class customers, although it is possible for customers to increase transaction limits by upgrading their accounts. This requires additional KYC details to be provided to the respective banks.

While we do observe some salient differences in terms of deposit rates and maximum limits for digital deposit accounts, we expect usage to be mainly driven by the allure of the credit products that are attached to such accounts. As other money management features are developed, we expect those will further determine successful uptake. Providers that are closely studying the financial management habits of mass market customers; pushing innovation to provide those customers with targeted services; and investing in the streamlined roll-out of those services, will be the winners in this industry.

For now, in terms of digital banking the KCB M-PESA Account seems to be the one to beat, but it is still new and we still need to see that customers will pay their money back.

Each day the battle for market share begins anew. The Kenyan market is certainly complicated at the moment. Providers are pushing the frontiers of mobile based financial services, and it will be very interesting to see who is left behind as the industry steams ahead.

Note: These prices were collected in November 2015 by reviewing provider websites and advertisements; by reviewing terms and conditions; and by calling customer service centres when necessary. It is important to note that volatile market interest rates and dynamic competitive pricing schemes mean that prices change constantly. Further, in multiple cases we received conflicting information from providers on their pricing schemes, and did our best to resolve them.

Competition in the Kenyan Digital Finance Market: Digital Credit (Part 2 of 3)

This is the second blog in a three part series, which compares digital financial service offerings in Kenya. The first blog focused on mobile money services and this second one delves into mobile banking services, focusing on digital credit. These are certainly the most complicated but also the most exciting services given their potential to deepen financial inclusion and create new revenue streams in the industry.

This is the second blog in a three part series, which compares digital financial service offerings in Kenya. The first blog focused on mobile money services and this second one delves into mobile banking services, focusing on digital credit. These are certainly the most complicated but also the most exciting services given their potential to deepen financial inclusion and create new revenue streams in the industry.

Competition in Digital Credit

Over thirty years of microfinance experience has shown that credit really has the ability to attract clients who are looking for both short term liquidity to help manage their money, but also want to borrow lump sums of money to help them make investments and pay larger expenses like school fees. To analyse credit products, we should look into at least three different aspects: the amount of the loan; the cost of the loan; and the repayment terms.

In terms of amounts that can be borrowed, digital lending products allow very small loans, even lower than the values offered from microfinance institutions. These loans are targeted at a specific market; they cover situations where someone needs to borrow just enough money to get on a bus, buy some vegetables for a meal or even pay for electricity tokens. However one of the issues cited in the past has been that the loans are only enough for these short term liquidity needs, and cannot cover investments, or large expenses like school fees.

.jpg)

However, with the new generation of products, that is no longer a valid concern, as the KCB M-PESA Account offers loans of up to one million KSH (~US$ 10,000) and Equitel also offers loans of up to US$ 2,000. However, the frequency with which people are approved for such large amounts is still an important issue, and it was noted in the past that the sizes of approved loans for M-Shwari (shortly after its launch) were actually much lower than the upper limit.

The cost of the loan is a complicated consideration, as it depends on the borrower’s digital credit score, the term of the loan, and the design of the product. M-Shwari and Equitel only offer something akin to an overdraft facility for one month terms. Both KCB products on the market offer lending terms which are much more flexible as they range from one to six months, and reflect the greater borrowing limits of its products, especially the KCB M-PESA Account.

M-Shwari has designed the cost of this borrowing as a fee of 7.5% of the value of the loan, which can then be doubled if the loan is not repaid in the first 30 days. Equity uses a more traditional interest rate, but varies it according to the digital credit score of the client, capping it at 10%. It is therefore very difficult to compare the price of Equity’s loan to the price of the one offered by M-Shwari even though both have the same 30 day repayment term.

The KCB products, which offer a 6% rate on a 30-day term, seem to be better deals than M-Shwari. However more in-depth analysis is needed, as the KCB M-PESA Account does not disburse the full value of the loan. It deducts the cost of borrowing upfront, and therefore increases the real rate of interest charged. Comparing the KCB products to Equitel for a one month term is difficult as well, as the range of Equitel interest rates means it could offer a better or worse deal on a case-by-case basis.

However, it may be reasonable to surmise that on average the KCB M-PESA Account will probably provide the best rates for a 30 day loan for the majority of Kenyans that are not already active Equity clients. This is because both M-Shwari and the KCB M-PESA Account have partnerships with Safaricom, and therefore have access to the customer profiles of Safaricom’s 23.35 million customers, and this better informs their digital credit scoring algorithm. In comparison, Equity has data on a much smaller number of customers to use for its credit scoring algorithms.

Theoretically this should mean that the KCB M-PESA Account has more accurate credit scores on the large number of Kenyans that are not KCB or Equity clients, yet have a Safaricom SIM, which should reduce the risk of lending and therefore the cost of lending. However, more testing of the systems is required to see if this advantage actually does lead to lower lending rates, and also if the credit scoring based on GSM data is good enough to keep repayment rates high and products like M-Shwari and the KCB M-PESA Account on the market in the long term.

In terms of digital credit, the KCB M-PESA Account seems to have the best value proposition as it offers competitive prices, the largest value loan, and the most flexible terms, and hopefully it will be able to keep potential risk under control. While the cost of borrowing for a term of 30 days is complicated, for values over $2,000 and for terms longer than 30 days, it is the only product on the market for now. Furthermore, with a reported almost two million registered customers in its first three months of operations, it seems that many Kenyans agree.

In the third blog in this series, we examine digital deposit services. These products are important as intuitive money management products are very attractive to customers and this can really drive increased usage and thus expand financial inclusion.

Note: These prices were collected in November 2015 by reviewing provider websites and advertisements; by reviewing terms and conditions; and by calling customer service centres when necessary. It is important to note that volatile market interest rates and dynamic competitive pricing schemes mean that prices change constantly. Further, in multiple cases we received conflicting information from providers on their pricing schemes, and did our best to resolve them.

Competition in the Kenyan Digital Finance Market: Mobile Money (Part 1 of 3)

There has been a great deal of international discourse on the topic of mobile money after Kenya’s successful implementation of M-PESA, and as we recently wrote, the success is increasingly shared by banks. This is a clear victory for Kenyan customers, who now have more options to choose from. However it also means that the financial landscape is more complicated as there are so many products and services to learn about and so many pricing schemes to understand. This leads us to the big question – who is offering the best deals in digital finance in Kenya right now?

There has been a great deal of international discourse on the topic of mobile money after Kenya’s successful implementation of M-PESA, and as we recently wrote, the success is increasingly shared by banks. This is a clear victory for Kenyan customers, who now have more options to choose from. However it also means that the financial landscape is more complicated as there are so many products and services to learn about and so many pricing schemes to understand. This leads us to the big question – who is offering the best deals in digital finance in Kenya right now?

We compared products in three categories in order to conduct an accurate analysis of the competition in the Kenyan digital finance market:

- Mobile Money

- Digital Deposits

- Digital Credit

Before entering into this analysis, we took a quick look at the pricing of GSM services between telecom providers, because for many Kenyans this will be the first decision they make determining which mobile/digital financial services they will use. It was interesting to note that of the four providers, Safaricom, Equitel and Airtel all had the exact same rates for voice and SMS services, while Orange prices were lower on voice, but equivalent on SMS. This shows that providers are generally not focusing on differentiating themselves on this dimension, and also there is no price advantage to the customer for selecting a provider with greater market share, because even the cross network pricing is standardized across providers.

In comparison, we see much more differentiated pricing schemes in the mobile money space.

All the telecom companies analysed offer mobile money services, and so do independent third parties like Tangaza and MobiKash. While most banks technically offer digital access to bank accounts, as opposed to mobile wallets, the service basically functions in the same way for cash-in, cash-out and money transfers, so Equitel and KCB Mobi Bank are also included in the analysis.

With mobile money, there are a number of important factors a customer should take into account when choosing a provider. In addition to a SIM card, you need a method for getting money into and out of the system, which is usually done through a network of retail agents. The Helix Institute conducted a survey of agents in Kenya in December 2014, and found that 79% of agents in the market were offering M-PESA, while 8% were serving Equity Bank, and 5% were serving Airtel Money. The remaining providers had lower percentages of the market. This means M-PESA agents are ten times more prevalent than agents for any other provider, and that is certainly a distinct advantage for customers.

We also examined the prices for the cash-in and cash-out transactions conducted through the agents along three generic bands (1,000 KSH [US$10]; 5,000 KSH [US$50]; 10,000KSH [US$100]). All providers offer the cash-in service free of charge. Interestingly, for cashing-out of the system through an agent, the KCB Mobi Bank service is the lowest price across all three values, and M-PESA is the most expensive across all values, whereas the other three services cost exactly the same. Therefore for transactions on the agent level, M-PESA is by far the most accessible, but customers must pay a premium to use it.

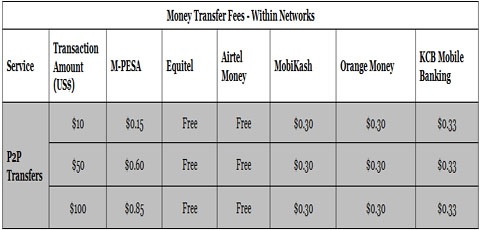

The person-to-person (P2P) transfers can occur within a provider’s network, or between provider’s networks. While the former is much more common, the latter is generally more expensive and providers have different pricing schemes for it, meaning the analysis for each must be done separately. In September 2014, InterMedia conducted a survey in Kenya and found that 58% of Kenyan adults actively used mobile money (on a 90-day basis). 99% of them used M-PESA, while 9% used Airtel Money, and 2% or less of the adult population used each of the other services. This was before Equitel was launched.

While it is clear that M-PESA offers customers a distinct advantage in terms of accessibility of agents, and number of users, the pricing of these services is complex and which service is the best deal still really depends on what a customer wants to do.

For transfers within a system, Equitel and Airtel Money offer free transfers right now to customers of their respective services. Beyond that, M-PESA has the lowest price for transferring US$ 10, but at the US$ 50 mark, M-PESA is the most expensive of the services, and MobiKash and Orange Money become competitive capping their fees at US$0.30.

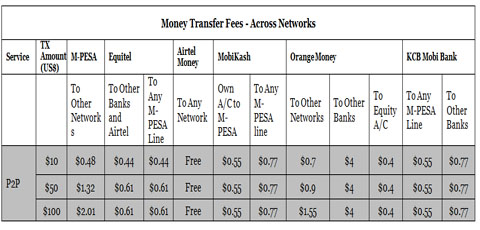

Transferring money across networks is much more complicated, and it is still unclear how important these pricing structures are given that 99% of users have M-PESA, and therefore may have little need to use another network. However, this is likely to change as banking services are becoming more integrated into mobile money, and competitors are investing in building agent networks that will make their products more accessible, likely eroding some of M-PESA’s market share.

Analysing the current pricing, Airtel continues to provide these services free of charge across all price bands to try and encourage people to use their SIM to send money. Equitel currently provides the most affordable option for transfers from mobile network operators (MNOs) to banks or vice versa. M-PESA is generally expensive for cross network transactions, especially at the higher transaction bands. It is also interesting that it is still beneficial for a customer to transfer to M-PESA using M-PESA, rather than use any other providers’ service besides Airtel, up to values of about US$ 50, at which point KCB Mobi Bank and Equitel become the lowest cost options.

Safaricom’s M-PESA is still by far the most accessible service in the country for cashing-in or cashing-out of the system. However, The Helix Institute 2014 Kenya Country Report did show that other providers are rapidly gaining ground. Currently, Airtel is the low cost provider, offering free transfers even to other networks. While this may help them gain market share in the short run, it seems unsustainable in the long run, and we predict these low prices will be temporary as they have been in the past.

For transferring money, in most cases the receiver will be an M-PESA customer, and for values up to around 5,000KSH (US$50), M-PESA will still be the preferred provider, except for the 9% of Kenyans with Airtel Money. However, services like Equitel and Airtel offering free transfers between users could be enough to increase their market shares, and that could put downward pressure on pricing for P2P transfers. For now, despite higher pricing in some categories, M-PESA still seems to be the obvious choice for Kenyans who like its accessibility, ubiquity and competitive pricing on the low transaction bands they use most.

In the second blog in this series, we examine digital credit services. Digital banking (deposits and credit) is potentially the most lucrative area of all, as digital loans and intuitive money management products are very attractive to customers and this can really drive increased usage and thus expand financial inclusion.

Note: These prices were collected in November 2015 by reviewing provider websites and advertisements; by reviewing terms and conditions; and by calling customer service centres when necessary. It is important to note that volatile market interest rates and dynamic competitive pricing schemes mean that prices change constantly. Further, in multiple cases we received conflicting information from providers on their pricing schemes, and did our best to resolve them.

Balancing Left-Right Bias in User-Centric Design Processes

Success of any product ultimately depends upon whether clients prefer, choose and use it. Understanding clients’ life and mental models, therefore, is a prerequisite first element for product design. However, researchers and designers often overlook the second element – the organisational buy-in and strategic feasibility of the creative ideas. Market research and user-centric design starts to look less meaningful when excellent product ideas are not adopted by the institution. We credit this failure to lack of focus to address the left brain and right brain bias.

The left and right hemispheres of our brain process information in different ways. While creative work and ideas are attributed to the right brain, the left brain is considered responsible for logical and analytical thinking. In terms of product design, institutions and investors tend to design products focusing on business logic and performance analysis; while researchers and designers promote creativity and innovation in design.

In this Note, we discuss MicroSave’s MI4ID approach to Concept Distillation and how it balances these biases in the product development process. The Concept Distillation process of MicroSave’s MI4ID approach provides as many creative and disruptive ideas as possible, yet is able to cull out ideas that are not strategically feasible. This Note gives glimpse of the approach through which MicroSave is able to engage business managers in design process and ensure ownership and feasibility of the product designed.