Interoperability of mobile financial services potentially offers great benefits for the wider ecosystem. The value to consumers is obvious. This, in turn, leads to wider adoption; higher transaction volumes; greater velocity of money in the ecosystem; all of which are advantageous to service providers. It is now well established from both MicroSave’s Helix Institute of Digital Finance and CGAP studies that non-exclusive agents transact and earn more than exclusive agents. For the regulators, this translates to the reduction in cash; expansion of the formal financial economy and a direct impact on advancing financial inclusion.

The launch of M-PESA in Kenya in 2007 catalyzed a worldwide ‘mobile money movement’ and as services have proliferated, the pressure to create interoperable mobile money systems has mounted. Today, the development of an interoperable mobile money ecosystem is a prevailing need. During 2014, 9 mobile network operator groups (Bharti Airtel, Etisalat, Millicom, MTN, Ooredoo, Orange, STC, Vodafone, and Zain), have pledged to offer interoperable mobile money services across Africa and the Middle East. The question of interoperability is no longer of if, but of when.

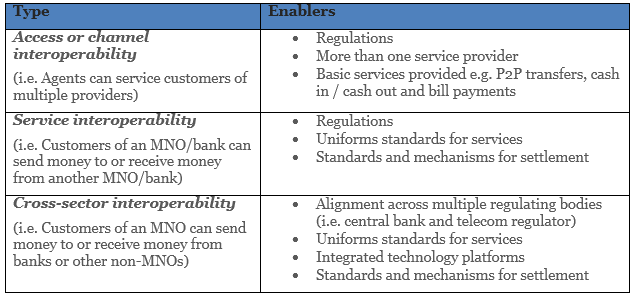

Interoperability crosses many levels. For example, access or channel interoperability, service interoperability, and cross-sector interoperability. The below table provides examples of levels and their enablers:

From the consumers’ perspective, interoperability means more convenient and efficient services. Interoperability also has a key role to play in advancing financial inclusion.Furthermore, one of the main barriers to mobile money adoption cited amongst customers in Africa and Asia is related to the inability to send and receive money irrespective of provider. Many factors, including market conditions, will dictate how and when interoperability graduates from the very basic to eventually reach a state of full interoperability. Agent or channel interoperability can be introduced relatively easily, with low investments and mainly through regulations. Although, the key barrier is to bring competing market players together to offer even the simplest form of interoperability. Higher levels of interoperability(often referred to as account-to-account interoperability) need bilateral or multilateral agreements; investments in technology capabilities to integrate services across providers; and implementation of common risk management practices. These are more complex to implement.

Even the simplest kind of channel interoperability in the form of agent sharing has a significant bearing on consumer experience and agent income. Apart from the convenience of improved access and networks effects, it increases market competition and therefore enables the resultant benefits in terms of lower tariffs, better service quality, and greater consumer centricity. In most markets, the dominant player would tend to resist even a rudimentary form of interoperability, for fear (often unfounded) of losing out, even though the strategy is rather expensive and difficult to execute. The introduction of the non-exclusivity of agents in Kenya is a welcomed step and early signs of impact are already evident. Reserve Bank of India, the central bank in India, has been toying with the idea of white labeled agents (business correspondents), that can be a channel for any service provider.

Account to account interoperability is more complex and has major implications for the service providers. There are multiple models through which account-to-account interoperability can be implemented. The easier forms are bilateral arrangements between providers. The more complex forms are multilateral arrangements; common processing entity with or without commercial interests; or arrangements through automated clearing houses (ACH). India, through IMPS system, provides a great example of infrastructure built to allow payments to be made across multiple MNOs and banks. Interoperability between platforms and services can be a costly endeavor and could, in fact, make mobile money services more expensive to the consumer. This can be offset once network effects come into play and volumes pick up, leading to economies of scale.

Yet, interoperability is not such a straightforward issue. Some would argue that if market interoperability happens too early, there is a risk of stalling mobile money movement before it even starts. At inception, it is a matter of significant investments with limited returns. Unless global standards evolve and network effects occur quickly, interoperability can be a barrier for the first movers in the market to invest. We have witnessed with Safaricom in Kenya, MTN in Uganda and Vodacom in Tanzania that return on investment typically takes between 5-6 years from the launch of service. These operators became profitable without interoperability. It might be argued that the lack of interoperability did, in fact, enable profitability. Without interoperability between service platforms, the cost of offering mobile money and running out of e-money is enhanced because non-exclusive agents have to hold a separate float for each provider. In Uganda, agents turn away, on an average, 3 transactions per day for want of float; in Tanzania, they turn away 5 transactions each day, dissatisfying customers and negatively impacting their bottom lines. A layer of complexity does get added to the agents’ business model as they will be managing e-money floats between different providers, instead of just one.

Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania are advanced mobile money markets. Interoperability makes sense in these countries, where there are multiple providers, most of whom have experienced the business benefits of offering mobile money products; and enough customers and transactions to not consider interoperability as a threat but an enabler to commercial business.

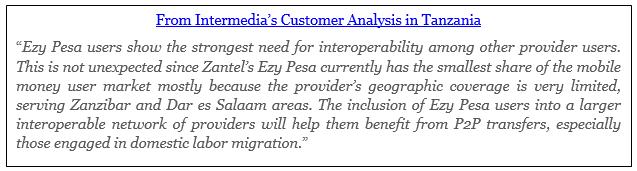

Even though Kenya is one of the most mature markets, interoperability has only recently come to pass in the form of agent sharing. For years, Safaricom reigned supreme over the mobile money kingdom, despite there being 5 other providers. Safaricom’s M-Pesa service still controls circa 67% of the Kenyan mobile money market, partly due to its early agent exclusivity arrangement, which is no longer in place and was formally outlawed in July. The Central Bank of Kenya ordered Safaricom to open up the M-PESA agent network to other operators in a bid to improve fair competition and encourage lower fees for customers. It will certainly be easier to achieve interoperability when the providers’ market shares are more even as in Tanzania (Vodacom 35%, Airtel 31%, Tigo 31% and Zantel 12%) than in markets with one predominant player (as in Uganda or Kenya).

Safaricom did have the first mover advantage in Kenya, but invested significantly in building and maintaining an extensive and robust agent network, so it’s no wonder that they may feel they are being treated inequitably now that competitors can simply use any of the agents they nurtured. For that reason, pioneers in other markets may feel disadvantaged too.

In any case, the initial cost and lower revenues that may result from interoperability are short terms. Taking a long-term view, interoperability can prove to be very beneficial to all the stakeholders. Historically, when interoperability has been introduced in the world of payments, be it with ATMs, credit or debit cards, huge growth and adoption have followed suit. Global standards for interoperable mobile money services will go a long way in presenting greater value to first movers and early adopters in the emerging markets. Just as standards like the ISO 8583 enable debit and credit cards at any ATM to transact with any bank around the world, it is desirable that similar standards are established for connecting mobile money services and making them interoperable.