Digital Financial Services (DFS) offers the potential to bring billions of previously financially excluded customers into the ambit of formal financial services.

It has the power to transcend the barriers of financial exclusion as it reduces the costs associated with the small value transactions; reaches out to larger numbers of people with innovative, low cost technology (mobile phones, card based systems, POS machines etc) and delivery channels (airtime sellers, grocery shop owners etc.); overcomes the issue of lack of physical infrastructure needed to distribute the financial products.

While there is a huge opportunity to leverage digital technology, there are challenges that can potentially hamper the potential.

Some of the challenges are:

- Increasing frauds, whether they are consumer driven, agent driven or system driven;

- Low consumer awareness (both about technology and financial services);

- Low agent awareness and inadequate investments in agent training; and

- Emergence of new and varied types of risks, pertaining to processes, technology, marketing / communication, liquidity management etc.

These challenges have implications for:

- The financial inclusion agenda as the frauds/poor client protection affects trust (of clients in the solution and on the system) and thus of the product uptake.

- Uptake of the products and service as low trust in service can impede the service take-up.

- The business case for agents and for the sector as a whole as the low take up not only from the customers, but also from the agents as it reduced the business case.

- The costs – both financial and non-financial. There are high costs – for business, customers and agents – due to increased transaction costs due to frauds, risks, increased charges for customers, etc.

The players in the digital finance space should bring in lessons on ‘responsible services’ from the financial sector so as to prevent negative consequences of frauds and risks.

Responsible Finance by definition means offering financial services in an accountable, transparent and ethical manner.

In traditional finance, it meant to be a guiding principle for the financial service providers to incorporate transparency, full disclosure, privacy of data, high quality standards in products and services, fairness in pricing, dignified treatment of clients, provision of complaints redressal mechanism in their practices. This typically resulted into activities around customer protection, targeted financial education training, building staff capacities, governance among other things.

In the digital finance space too, the elements of what makes the services ‘responsible’ remains the same, but with the complexities introduced by the technology, eco system and scale.

- Several types of technology – mobile, POS, card based, internet etc – each of which comes with its own risks and challenges.

- Complex and overlapping processes at almost each level of the players.

- For an industry still struggling to prove and become sustainable, the “responsible” elements of advocacy should act as ‘enablers’ and not as ‘disablers’.

- Grey area of regulation or even self regulating standards.

- Double jeopardy of not only the consumer awareness, but also of the agent awareness.

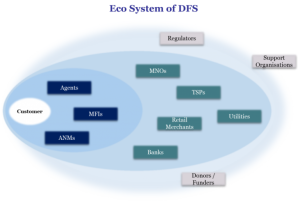

- Distances between the key players of the ecosystem. For instance, an agent might be hundreds of miles away from the agent network manager (ANM), thus making monitoring and capacity building difficult.

- Multiplicity of players and the complex web of roles. This makes fixing responsibility and bringing accountability that challenging.

Though regulators, support organisations and donors / funders are near the perimeter of the eco system, they play a critical role in risk management and fraud prevention.

- Regulators – by setting enabling guidelines for all the players to manages risks better and prevent fraud;

- Support organisations (consulting firms, training institutes, advocacy groups) – by building the capacities and capabilities of various stakeholders and sharing the best practices across geographies; and

- Donors / funders – by creating the right incentives for the players to adopt the right practices considering the customer protection and long term sustainability.