Speakers from SPTF, MSC and the Smart Campaign discuss the key insights from the analysis of digital credit in Kenya and the recommendations from the newly launched report ‘ Making Digital Credit Truly Responsible’ at the first webinar series on 25th Sept 2019.

DBT and FI in India

Financial inclusion in India received a huge boost, thanks to the PMJDY program, Aadhaar, and the expansion of mobile connectivity throughout the country; but the real catalyst is the country’s digital benefits transfer program.

Where are the women in the digital credit bandwagon? Lessons from Kenya

Seven years since the launch of digital credit in Kenya, women are still disproportionately under-represented among borrowers. Yet they offer immense potential—for providers with the right focus. Just as in many developing markets, the economic participation of women in Kenya is largely concentrated in the informal sector, where women participate in small businesses, farm on small landholdings, and work as laborers, among other professions. The digital avatar of credit is particularly well suited for this segment, as it can address some of the biggest challenges that women entrepreneurs face.

Access to credit is an important tool since economically empowered women are better equipped to achieve their goals. They are able to provide for their families, contribute to society, and advance their own rights. The instant, uncollateralized, and relatively hassle-free nature of availing digital credit makes it an effective tool for women to manage or smooth over emergencies related to income. It has the potential to play a direct role to advance Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE) and further the Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5) of gender equality.

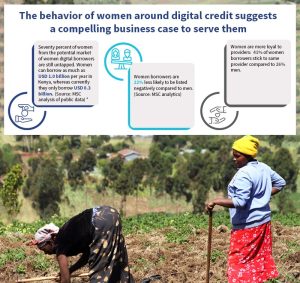

We are excited by the significant opportunity that digital credit offers in the current age, which is characterized by a rapid increase in access to mobile phones. At present, Kenyan women comprise just 37% of the digital credit user base, which amounts to a gender gap of 26%1. The participation of women in the digital credit market is even lower when we consider loan volumes—women borrow only 31% of the total value of digital credit loans1. This presents a significant opportunity for players in the digital credit ecosystem to expand their customer base. Yet gender inclusivity is one area that needs more work.

MSC’s recent study2 on “How to make digital credit truly responsible and transformative” highlights three key insights to make digital credit in Kenya more gender-inclusive.

1. Evidence suggests that women are more reliable and loyal borrowers and hence form a strong business case for providers to employ a gender lens.

Our research reveals two interesting behavioural traits of women borrowers:

Figure 1

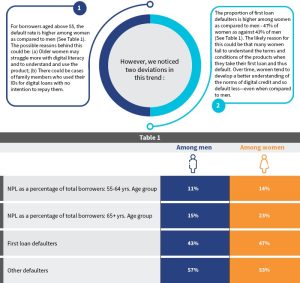

a) On average, women are less likely to be negatively listed as compared to men (See Figure 1). Women are more anxious about defaults and their consequences. They are also generally more risk-averse in nature. These reasons probably drive them to be extra cautious to repay on time.

b) They are more loyal to a specific brand and prefer to stick to one provider instead of experimenting with different ones3.

Men are more experimental and tend to use a number of digital credit providers while women stick to preferred providers. This indicates a need to tap into this tendency to be loyal to ensure a prolonged business relationship. Among those with multiple digital loans, 41% of women borrowers stick to the same provider, as compared to 26% of men.

The unmet market potential of women, their lower rates of default, and greater loyalty establish a strong business case for providers to onboard more female customers. Variation in reasons for taking digital loans among women indicates the heterogeneity in the segment. Providers have an important opportunity to recognize this heterogeneity of women as a segment and build a strategy focused on them. This strategy may include the design of segment-specific products and intuitive women-friendly digital interfaces along with gender-centric communication, among others. Providers that already operate on a large scale have a great opportunity to offer differentiated services for women.

Niche players who are committed to this goal also deserve greater support from the investors and regulators.

2. The organization of cost-effective digital communication campaigns with a human face is the key to attract more women customers

The study on “Digital Credit in Kenya: Evidence from demand-side surveys” indicates that women are 35% more likely to cite fear as a reason to not borrow compared to men. Periodic digital communication campaigns enable women to become better informed and may help overcome this fear. On-the-ground communication campaigns through influencers and opinion leaders are important to develop a loyal base of women customers who prefer, choose, and use digital credit.

Women are generally more cautious to adopt technology. Social proof is a key determinant of how low-income women adopt and use digital credit. Hence, incentives that align with peer recommendations can be an effective way for providers to reward women who help enroll other women.

3. A robust grievance resolution system with a human touch will help providers serve their women clients better

The current grievance resolution mechanisms (GRM) rely largely on the use of SMS, call-centers, and emails. These mechanisms are “low-touch4” in nature and mostly unused by the customers. Our research indicates the need for various levels of “touch” depending on the customer segment. Women customers who fear digital loans and are extra cautious prefer high-touch communication channels, particularly when they try out a new product or seek to resolve their grievances. Adding a proactive human face to the GRM to provide quick, hands-on solutions for issues faced by customers is essential to gain their trust and serve them better.

Studies have established the importance of digital credit to help households meet their expenses. However, due to negative shocks, the difference in its impact based on gender is not clearly established. While we lack hard data, the presence of anecdotal evidence is sufficient to get us started on further exploration and research. The business case is evident and providers should not hesitate, as the early movers will likely reap significant benefits.

Our report based on our study of the digital credit landscape in Kenya (2019), discusses the changes in the digital credit landscape. It highlights the core challenges, emerging concerns and also goes further to formulate recommendations for both regulators and suppliers to make the delivery of digital credit more responsible and customer-centric. Read it here.

[1] MSC analytics

[2] Supported by SPTF and Accion Smart Campaign

*Estimated based on population, target age group, mobile phone availability, number of digital loans per year and an average value of each loan

[3] MSC demand-side research and analytics

[4] Lower level of human involvement in the GRM process from the provider’s side

Is there room for optimism in the Kenyan digital credit sector?

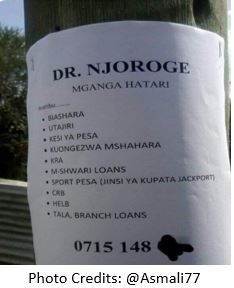

“Come and solve your problems related to M-Shwari, Branch, and Tala loans,” reads an advert from a local native doctor. These days, such adverts are a common sight across downtown Nairobi. While most Kenyans react to such “miracle cures” with disbelief, the prevalence of such posters is a reaction to the real struggle that Kenyan digital borrowers continue to face. A typical Kenyan digital borrower juggles three loans and struggles to repay on time, despite the fact that these are relatively small loans.

“Come and solve your problems related to M-Shwari, Branch, and Tala loans,” reads an advert from a local native doctor. These days, such adverts are a common sight across downtown Nairobi. While most Kenyans react to such “miracle cures” with disbelief, the prevalence of such posters is a reaction to the real struggle that Kenyan digital borrowers continue to face. A typical Kenyan digital borrower juggles three loans and struggles to repay on time, despite the fact that these are relatively small loans.

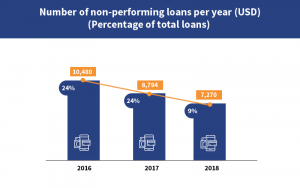

Among borrowers in Kenya, 2.2 million individuals have non-performing loans for digital loans taken between 2016 and 2018. About half (49%) of the digital borrowers with non-performing loans have outstanding balances of less than USD 10 . This narrative of over-indebtedness has also been a mainstay in the media, with a number of news articles highlighting disturbing trends and statistics from the sector.

This begs the question: Can we attribute any positive outcomes to the evolution of digital credit products and the growth of the sector in the past seven years? In a recently published study on the digital credit market in Kenya, MSC analyzed supply-side data from 2016 to 2018. The study findings indicate some positive and encouraging signs for the sector. In this blog, we look at these signs in detail.

[1] MSC analysis of supply-side data from 2016 to 2018

What is the good news?

1. Digital credit has broadened access to credit, particularly for those previously left out

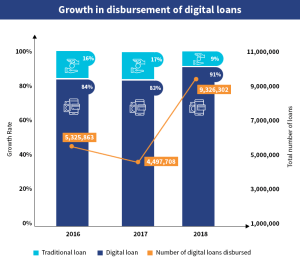

The digital credit sector has experienced significant growth. Our analysis shows that in the past three years, the number of digital loans disbursed has approximately doubled. In the same period, most of the loans (91%) were digital in nature. A key implication of this is also a broadening of financial inclusion in general. The latest FinAccess Household Survey is a testament to this, showing an increase in financial inclusion in the country from 75% in 2013 to 89% in 2019. This has largely received a boost from the ubiquitous nature of mobile financial services in the country.

2. The data reveals an improvement in loan quality

Almost a quarter of all digital loans issued in 2016 were non-performing. However, this figure had dropped to 9% for loans issued in 2018 by the end of that year , showing a 15% improvement in NPLs as a percentage of the total digital loans. In particular, MNO-facilitated lenders have managed to improve their loan quality compared to fintechs and banks. This is indeed remarkable.

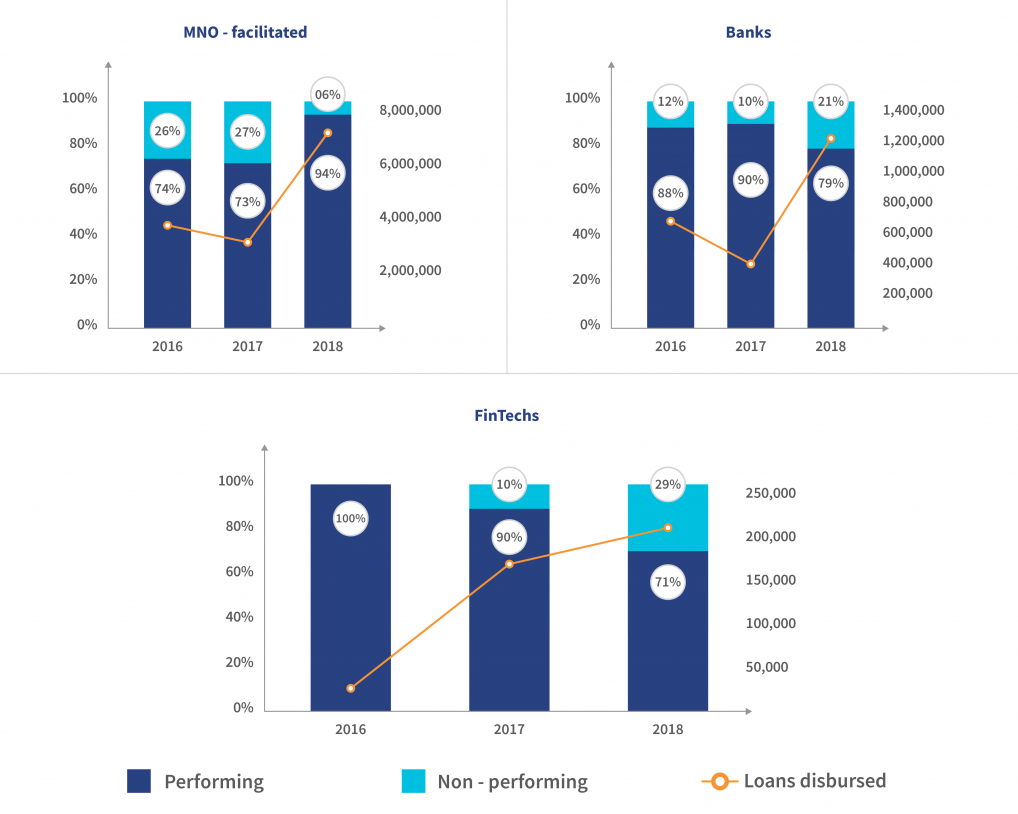

Loan disbursements and book quality per provider

[2] This figure reflects loan performance as captured by supply-side data as of end-2018. It rose to 11.75% as of August, 2019.

Further analysis of disbursement and loan quality

All suppliers have generally increased their loan volumes from 2016 to 2018. With an increase in portfolio, we can expect an increase in NPLs. However, the key MNO-linked suppliers have managed to increase both quantity and quality of loans, as seen from the data in 2018.

We think that this is largely due to a number of reasons. First, these suppliers enjoyed a first-mover advantage, which has provided them with robust customer data—both from mobile money historical payment transactions and from a longer digital credit history to underpin their credit assessment. In particular, Safaricom has data of millions of loyal customers who use their wide range of services. Second, this first-mover advantage has also allowed time for continuous improvement of their algorithms for credit assessment. Safaricom has since started selling the credit scorecard for its customers to other providers in the market. However, it still enjoys the prerogative of deciding which suppliers can access this data.

What could be leading to better loan repayment?

Increased awareness of the consequences of loan default

In our qualitative interviews with 50 digital borrowers, we found that they are increasingly aware of the impact of defaulting digital loans. They know that they risk being negatively listed in the credit bureaus, which would lower their credit score and limit them from accessing formal credit. Further, most clients are willing to repay the loans mainly because of their innate nature or due to their need to retain and increase their loan limits and maintain access to the loan.

Improvement in credit scoring

Our engagement with the lenders revealed that their loan assessment algorithm has been getting better over time. The accuracy of credit scoring continues to improve with usage. The lenders have adopted a test-and-learn approach where they use the initial stages of the product to learn the financial behaviors of their customers, which include saving, borrowing, repayment, and defaulting. The inputs improve the accuracy of predictive analytics through machine learning. For example, M-Shwari piloted their product for 18 months. This allowed sufficient time to collect data that would support in predicting the performance of future borrowers.

Now that players in the industry have gained experience and showed positive trends, what would we like to see in the future?

• Improvement of the products offered to ensure that they are customer-centric: Nearly all the products from lenders have similar features. Their tenure is mostly one month and the monthly interest rate is around 7.5%. On the contrary, the needs of customers are diverse and thus require differentiated products. A handful of lenders have been focusing on the underserved segments. FarmDrive is an example of a fintech that lends to small-scale farmers with products that are designed specifically for the market segment. In addition, products like AfriKash, which focuses on informal women traders, offers flexibility in repayment that rewards those that repay early.

• Regulation of the sector: The regulatory architecture that governs digital credit requires a coordinated effort to be reformed. Largely, we may consider the sector to be regulated. This is because MNO-facilitated lenders and banks, which enjoy the biggest market share, are fully governed. However, fintechs remain largely under-regulated. They have recently formed their own association with 11 members, dubbed the Digital Lenders Association of Kenya (DLAK). The DLAK aims to strengthen the sector with best practices and consumer protection. The introduction of data-protection draft bills for legislation in July 2018 and the reform of credit data reporting templates are steps in the right direction. However, much more can be done.

Our report based on our study of the digital credit landscape in Kenya (2019), discusses the changes in the digital credit landscape. It highlights the core challenges, emerging concerns and also goes further to formulate recommendations for both regulators and suppliers to make the delivery of digital credit more responsible and customer-centric. Read it here.

Making digital credit truly responsible- Insights from analysis of digital credit in Kenya

Digital credit is instant, automated, and remote, providing borrowers with quick access to short-term loans. The relative ease with which providers can reach the mass market has profound implications for the future of financial services. The potential for financial inclusion is unprecedented. However, it is up to all financial sector stakeholders to ensure that digital credit is beneficial to borrowers.

During the first half of 2019, MSC was commissioned by SPTF and the Smart Campaign to undertake a comprehensive study on the current state of digital credit in Kenya. This study revealed:

- Across Kenya, 16.4 million loans have been disbursed digitally since the launch of the first digital credit offering seven years ago. In the past two years alone, the number of digital loans issued has approximately doubled;

- Between 2016 and 2018, 86% of the loans that Kenyans took were digital in nature, which reflects the increasing popularity and the pervasiveness of this channel;

- While the sector has seen almost 50 fintechs enter the field in the past four years, bank- and MNO-facilitated products still dominate the market and amount to 97% of the supply;

- Among borrowers in Kenya, 2.2 million individuals have non-performing loans for digital loans taken between 2016 and 2018. About half (49%) of the digital credit borrowers with non-performing loans have outstanding balances of less than USD 10.

Based on MSC’s comprehensive study of the state of the digital credit landscape in Kenya (2019), highlighted some positive signs and some persistent problems, as well as opportunities to improve products and consumer protection.

It highlights the core challenges, emerging concerns and also goes further to formulate recommendations for both regulators and suppliers to make the delivery of digital credit more responsible and customer-centric.

Making digital credit truly responsible

This video reveals some of the key findings of our recent research on digital credit in Kenya. It also invites participants to join us for a webinar series that discusses the key insights, challenges, and recommendations to make digital credit truly transformative. Watch and learn more.