Download the event agenda here.

Direct Benefit Transfer in Fertilizer: Fourth round of concurrent evaluation—A nationally representative study

DBT in Fertilizer (DBT-F) is a modified subsidy payment system under which the government remits subsidy amount to fertilizer companies after fertilizer retailers have sold fertilizer to farmers through successful Aadhaar-based authentication. The government launched DBT in fertilizer at a national scale over four phases between September 2016 and March 2018. On the request of the NITI Aayog and Department of Fertilizers, MSC conducted the evaluation of each phase. The first three rounds of the evaluation consisted of the pilot districts, while the fourth round included the pan-India rollout.

This report provides detailed findings from the evaluation conducted in the fourth round for fertilizer retailers and farmers on training and awareness, transaction status and experience, compliance with processes, grievance resolution mechanisms (GRM), and farmer feedback on DBT-F and the cashless payment system. This report provides recommendations to aid policy-level decision making and improve operations on the ground.

Experimenting with cash transfers in food subsidies – Lessons from the pilot in Nagri

This case study discusses a unique experiment of distributing food subsidy in the Nagri block of Ranchi district, Jharkhand, India. The Jharkhand government experimented with an innovative delivery model in the hope to reduce leakages in the public distribution system (PDS). The model derived its design from PAHAL-mode of LPG subsidy distribution. MSC conducted a comprehensive evaluation study and found that at both the institutional and ecosystem levels, a lack of sufficient infrastructure precluded successful implementation leading to premature closure of the scheme.

The primary reason behind the rejection of the new model was that the Nagri pilot created significant operational challenges—both for beneficiaries and for fair price shop (FPS) dealers. This case study discusses the learnings and insights from the Nagri pilot that the governments can use to inform future experimentation in food subsidy delivery.

Why does research matter in human-centered design

The inevitable is hidden and forgotten

Human-centered design (HCD) continues to ride a wave of popularity across sectors. The approach, if applied correctly, has the potential to generate effective, customer-centric insights. These insights can be used to develop innovative solutions that create enduring value for customers and organizations. HCD involves an empathetic understanding of users, creative thinking, and rapid testing of solutions.

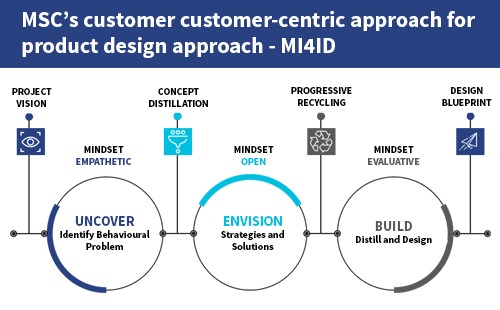

When an organization adopts an HCD approach, it increases the chances to obtain better and timely insights from customer engagement and thus be able to design and deliver appropriate services to customers. HCD not only benefits the organization by addressing business problems but also allows active collaboration that can empower customers to express their needs, preferences, and aspirations. MSC has used our flagship version of HCD, Market Insights for Innovation & Design (MI4ID) for two decades now. As we celebrate 20 years of work, we examine the one thing that makes MI4ID so successful.

Many solutions developed using the philosophy of HCD have not yielded great results—for example, here and here . While there is no question of the intent, desirability, and appropriateness of using HCD, these failures indicate that HCD-based solutions often stumble due to a lack of supply-side buy-in and a poor understanding of both internal and external market players beyond the end customer. Repeated “pivoting” to new solutions is not a badge of honor—it is a sign of inadequate research that underlies the design of the initial solutions.

One example where HCD could have been applied with more rigor is a particular case where the low enrolment for a product was attributed to poor awareness among potential customers. Developed using the HCD approach, the proposed solution was a smart, digital platform-based community financial literacy and marketing program. However, the solution was developed using insights from hastily conducted research, which revealed that WhatsApp was a common source of information and that the servicing agent had less time or capacity to share knowledge. The solution also proposed an element of gamification, whereby if one person views all the suggested videos and responds to some questions, they will be entitled to some “freebies”.

However, the researchers missed a key insight. The real obstacle was not the customer’s knowledge, as they were already receiving basic knowledge from the agent—who was a trustworthy and influential source of information. Rather, the underlying issue was that potential users, as well as some existing users, had many queries that neither the agent nor other information sources could answer. Clearly, a contextual understanding and deeper customer insights would have highlighted the real issues, proposed a solution, and more importantly, improved the knowledge dissemination hierarchy. The proposed digital platform—however well designed, smart, and interactive—was not the solution in this case.

Similar challenges arise when HCD overlooks the contexts or the ecosystem of providers. In another HCD-led exercise, the proposed solution to enhance the adoption of mobile money by customers was to establish a model shop where the digital payment was accepted. The HCD process overlooked the fact that many shops in a nearby market-accepted cash, offered short-term credit, and were an integral part of the community relationships that villagers used to manage their financial affairs.

We have also witnessed many instances where HCD-led solutions have failed because of a partial involvement from service providers in the development of the solution or product or simply because the regulations did not permit the proposed product. Such examples indicate that research on the market and supply-side realities within which a solution must operate received inadequate attention.

We list below some limitations of HCD that providers, regulatory bodies, and other organizations should address.

- There is often a “need to find a quick fix” bias, owing to a shallow focus on understanding the context. A number of assumptions are made based on a few interactions mapped as per the work-plans and planned activities. As a result, a planning fallacy invariably ensues in the subsequent work.

- The HCD process simply tests “confirmation bias” as a pre-determined idea or “solution” from elsewhere—with minimal contextual changes. Practitioners often overlook local knowledge, realities, and ideas. Thus, they face inevitable challenges to adoption.

- HCD is limited by a “mind projection fallacy” bias, where HCD practitioners assume to have a thorough understanding of their strategy, trajectory, or regulatory environment. As a result, the proposed solutions are difficult to adopt for the organization in its existing strategic plans or as per the law.

- HCD practitioners often fall into the “outside expert” trap, where they do not spend enough time to understand the local context and lack sufficient local knowledge. They do not make the effort to put the right team and tools in place to understand the context, such as by developing and reading “research-guides”, understanding the local language used to describe complex human financial behavior, or conducting participatory exercises. This bias is often amplified by a failure to formulate questions because the practitioners assume that they “already know this well.” As a result, they do not formulate contextual questions. Moreover, such outside experts often use tools or games that are not adapted to the local market.

- While a persuasive and engaging presentation of ideas is immensely important, it may be used to obscure a lack of detailed assessment and analysis, also known as the “design chic” challenge. Indeed, the prevalence of teams spending more time designing presentations and reports than the actual fieldwork is a fairly good indicator of this problem.

Despite the inherent biases that flourish when practitioners carry out inadequate research, providers generally resist making adequate investments in research. Although providers acknowledge that disruptive thinking leads to solutions, they are often comfortable in carrying out cursory research that extends between five and 10 days and involves talking to 10 or 15 customers at most. The result of which is that they “mix and match” their lessons from other settings and test the design solutions hastily with end-users. This process overlooks contextual information including one’s decision-making process and the emotional and mental barriers, that is, the behavioral issues around critical questions, such as:

- Why do the end-users do what they do?

- What are the key socio-cultural barriers that hinder the desired behavior or goals?

- Where is the gap in converting intention into action?

- What are the behavioral triggers behind the end-users’ choices?

These elements must be uncovered before envisioning the design solutions.

Balancing the act: give research its due!

The HCD process, by itself, does not undermine or negate the importance of research. Yet somehow, research is relegated to solution testing, which takes precedence while the aspect of creative thinking is ignored. MSC’s product and service development toolkit “Market Insights for Innovation & Design” (MI4ID) stress research-driven insights before innovations can begin. MI4ID further stresses on the involvement of those on the supply side who are responsible for implementing solutions at an early stage. Read more about MI4ID and its success stories here.

It is essential to undertake adaptive research where intelligent moderation of field-discussion uncovers the nuances that surround the research issue. Most HCD research should use carefully selected combinations of interactive methods, such as discussions, games or participatory exercises, activity prototypes, observations, mystery shopping, among others, to decipher such nuances.

To obtain rich insights and understand the situation on the ground, providers should ideally recognize that research is an investment, one that is worth making to unlock value that endures—thereby realizing a strong return on investment well into the future while also serving happy customers. This requires an empathetic mindset that is hard to achieve by browsing data online or by simply interviewing a few people. Researchers need to spend time, align with the socio-cultural fabric, and assimilate with the wider societal dynamics to interact successfully with potential beneficiaries only then successful interventions can be designed.

The rise of gig economy and how its shaping the employment space in Africa

Youth unemployment in Africa is a present issue in the continent owing to the rapid population growth and lack of matching sufficient job opportunities. The gig economy has the potential to decrease unemployment rates amongst youth, through providing an avenue to meaningful engagement with the formal economy

Resolving challenges for digital credit with segment-specific vulnerabilities

Stanley is a 35-year-old trader who sells second-hand shoes in one of the largest open-air markets in Nairobi. He makes good profit during peak hours and often reinvests the amount into his business. At times when the profits drop and become irregular, Stanley often requires a line of credit to stay afloat. On average, he borrows USD 300 per month from digital lenders to replenish his stock. He repays the loans on time to avoid a reduction of his loan limit and being negatively listed.

Stanley is a 35-year-old trader who sells second-hand shoes in one of the largest open-air markets in Nairobi. He makes good profit during peak hours and often reinvests the amount into his business. At times when the profits drop and become irregular, Stanley often requires a line of credit to stay afloat. On average, he borrows USD 300 per month from digital lenders to replenish his stock. He repays the loans on time to avoid a reduction of his loan limit and being negatively listed.

Stanley is just one among the many digital borrowers who have improved their livelihoods successfully through digital credit. Seven years since digital credit emerged, almost 6 million Kenyans either have used the service or continue to use it. Yet the question remains—is the reach of digital credit wide enough to help all Kenyans who need instant credit? To answer this question, we interviewed a sample of 50 digital borrowers. We used our Market Insights for Innovation and Design (MI4ID) approach to gather insights on the use of digital credit, segment-specific behaviors, adequacy of customer protection, and product awareness.

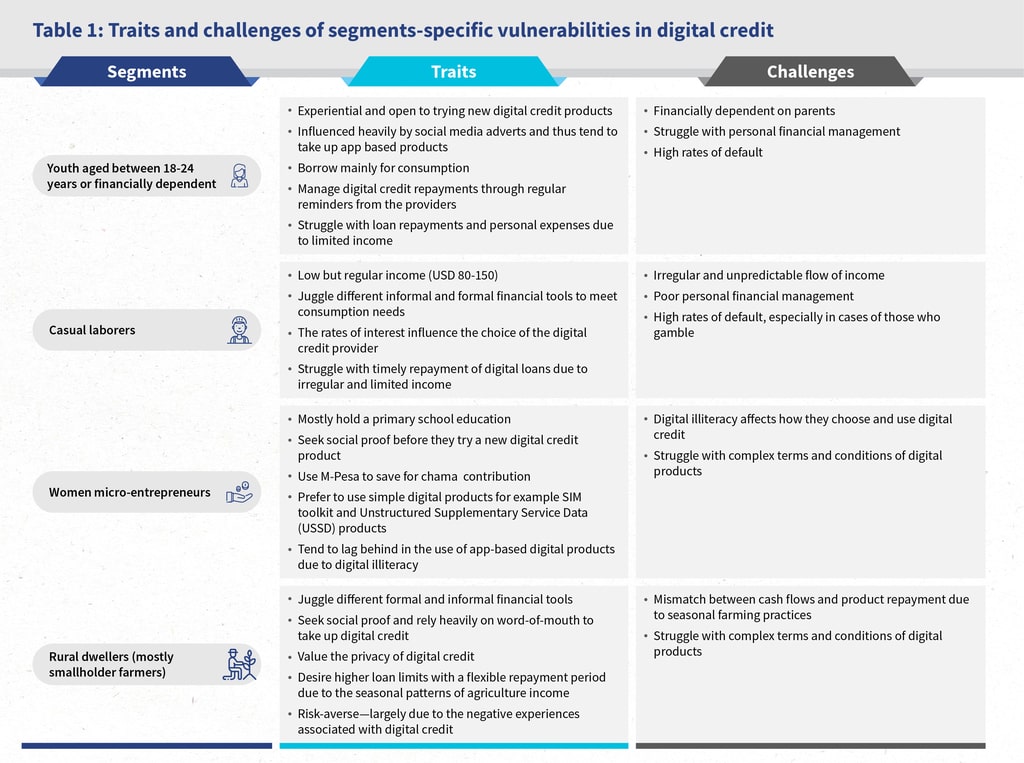

Our research focused on the neglected segments as elaborated in this report “Digital credit in Kenya: evidence from demand-side surveys”. In Table 1, we explore some of the traits and challenges of these segments that have resulted in low to moderate rates of uptake. These segments use nearly half of the total amount borrowed for consumption.

For digital credit to serve the marginalized segments, the lenders may address a few of the options, as listed below:

Appropriate product design

Adopt a customer-centric approach (see figure 1) to develop digital credit products that serve a majority of the segments. This would help avoid further exclusion for segments like farmers and women micro-entrepreneurs. Our MI4ID approach works on the premise that product development goes beyond the traditional process. The approach incorporates the principles of behavioral economics and human-centered design. At MSC, we believe that product development must be a two-pronged process—the generation of market insights, followed by innovation and design.

Figure 1: MSC’s customer-centric approach for product design—MI4ID

Suppliers who already operate at scale should work on more granular customer segmentation and tweak their product products and services appropriately. However, some niche players who are committed to this goal deserve better support, such as DigiFarm, Apollo Agriculture, and AfriKash

Box 1: The case of DigiFarm

In 2017, DigiFarm, an agricultural solution developed by Safaricom, partnered with FarmDrive to develop and launch a loan product. The product had flexible repayment terms that range from 30 to 120 days. As of May 2019, DigiFarm had registered over 1 million smallholder farmers on its platform who have access to digital input credit and harvest cash loans.

Use of cost-effective digital channels to communicate with the vulnerable segments

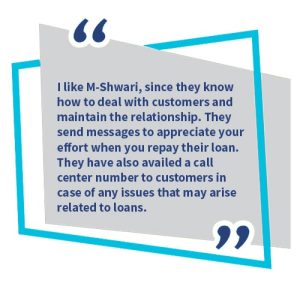

When it comes to customer engagement, specific segments, such as the rural people, do not find social media channels to be intuitive. This is because they prefer human interaction. Providers should include at least one channel that features a relatively higher “touch”. For instance, a customer care number introduces a human element that could be used for marketing and collection of loan repayments.

Product marketing as a tool to educate digital borrowers

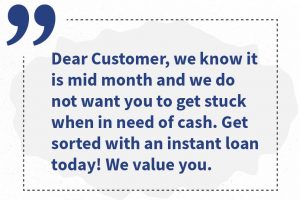

Nearly all of the digital lenders send emotive marketing messages to potential customers to persuade them to takeloans, as shown in the figure below :

However, the level of financial capacity is inadequate in some segments, such as the youth and casual laborers. They are easily influenced to take up digital loans. To encourage the responsible uptake of digital loans and higher rates of repayment, providers can introduce educational content into their product marketing strategies

Box 2: Case of Pezesha

Pezesha is a peer-to-peer digital marketplace that targets low-income borrowers in Kenya. Its customers have a data wallet that enables them to build and store their digital profile that they can use to access credit from formal lenders. Pezesha also focuses on financial education to promote and encourage responsible financial practices and credit uptake among digital borrowers. Through its solution, Patascore, the company offers financial education content that covers a variety of areas, such as savings and investment, effective debt management, ways to improve one’s credit score, and Credit Reference Bureaus (CRBs) and their role. In the event where a borrower is denied a loan, they receive tips on how to improve their scores and advice to re-apply later.

In just seven years since the advent of digital credit in Kenya, it has displayed a great potential to serve the marginalized segments. The development of more suitable products by the suppliers can prove to be a tremendous step towards the financial inclusion of these segments.

Our report based on our study of the digital credit landscape in Kenya (2019), discusses the changes in the digital credit landscape. It highlights the core challenges, emerging concerns and also goes further to formulate recommendations for both regulators and suppliers to make the delivery of digital credit more responsible and customer-centric. Read it here.

[1] Chama is a Swahili word for group savings