India’s National Food Security Act (NSFA), which came into effect in 2013, declared that the poor in urban and rural areas of the country had a constitutional right to food. The NFSA provides monthly food subsidies to roughly 800 million poor individuals in all 36 Indian states and union territories in the country. The subsidy is in the form of 5 kilograms of rice, wheat, or a combination of both. This system of delivering subsidies is known popularly as the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS).

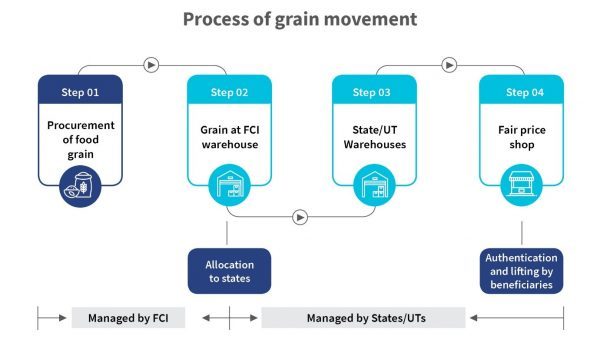

TPDS is a complex process of grain procurement from farmers, grain storage at warehouses or depots, grain allocation and distribution, and delivery to beneficiaries through licensed food distribution shops called fair price shops (FPS). These FPSs distribute food grains to NFSA beneficiaries every month. The TPDS chain encompasses around 2,000 depots—storage centers used to store procured grains safely—besides over 8,000 warehouses and a network of more than 500,000 FPS to facilitate movement and distribution of grains from farmgate to poor households.

The central and state governments co-manage the entire operation of moving grains from the farm gate to the NFSA beneficiary. The Food Corporation of India (FCI) manages the process of moving grains on behalf of the central government to the FCI warehouses after procuring them from farmers. The state governments and union territories handle the movement of the grains from the FCI warehouses to state-owned warehouses and then on to FPS dealers. The central government provides financial assistance for transportation and handling to states to ensure the delivery of food grains to each FPS. This financial assistance is capped at INR 100 (USD 1.4) per quintal (100 kg) to northeastern states and INR 65 (USD 1) per quintal to other states.

FCI has played a significant role in transforming India’s food subsidy delivery system to one that is stable and dependable. FCI procures food grains at the minimum support price from farmers in grains-surplus states—ones that produce more grain than they consume. It then distributes the grains to grain-deficit states and union territories. This daunting and massive task requires the movement of more than 4.1 million tons of food grains every month. It involves multiple steps, procedures, stakeholders, checks, and expenses that require on-the-ground daily management to ensure TPDS functions smoothly.

Vulnerabilities in the system

The complexity and scale of TPDS, however, introduce the scope for vulnerabilities in the system. The TPDS supply chain is notorious for operational lapses and leakages that range between 40 to 50 percent. The primary reason is that in the process of grain movement, food grains change hands or ownership multiple times through private transporters and warehouse employees who are hired through tenders. This leaves room for fraud and malpractice as the states’ capacities to monitor and check operational lapses regularly are limited.

Further, state food grain warehouses are often rented out. The renting entities are usually the state civil supply cooperatives, agriculture marketing cooperatives, or state warehousing cooperatives, none of which falls under the state food departments’ supervision. Additionally, the absence of automated protocols for quantity and quality checks makes the system vulnerable during the movement of grains.

“End-to-end computerization” of TPDS

The central government introduced “end-to-end computerization” (E2EC) of TPDS operations in 2012 to address the key logistical challenges of TPDS and improve food grain distribution across the country. The E2EC initiative had the following features:

• Complete digitization of the NFSA beneficiary database in all states and union territories;

• Online allocation of grains to states;

• Computerization of supply-chain;

• Transparency portal implemented in all states and union territories

E2EC works to revamp and strengthen TPDS and make the system more transparent, efficient, and accountable by making use of electronic solutions. A key initiative under the E2EC scheme is the Food & Essential-commodities Assurance & Security Target (FEAST). The FEAST module helps to automate and digitize stock inventory management, allocation policies, online generation of allocation orders, stock release orders, stock movement receipts, and delivery orders. Concurrent with the implementation of the FEAST module, other innovations have significantly improved the monitoring of grain movement and the availability of real-time grain inventory. These innovations include automated tracking of commodity movement using geo-positioning systems, digitization of grain weighing machines at warehouses, computerization of state-owned warehouses, and automation of FPS. Each FPS employs an electronic point of sale machines to record transactions and authenticates beneficiaries at the shop level.

We at MSC intended to gauge the efficiency in grain movement, flow of information, and sufficiency of the financial assistance given to states for transportation for the benefit of the Indian government. We conducted a comprehensive assessment of the TPDS supply chain in five states—Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Assam, and Uttar Pradesh. Results from the assessment led us to conclude that these states continue to use the resources available to accommodate the newer systems and replace manual processes that have defined their operations for years. However, the states face hurdles, as one supply chain system cannot be adapted to the disparate systems across the entire country.

The TPDS supply chain is mammoth, in terms of both geographic spread and population coverage. As a result, many factors including terrain, stakeholders, ground-level facilities, resources, and infrastructure affect the way the program runs. Automation requires not only buy-in from all stakeholders but robust IT infrastructure and network connectivity, all of which are either not available or are beset with challenges in India.

MSC observed that different states have been able to implement these changes in varying degrees. Telangana and Tamil Nadu were far more advanced with near-complete digitization of their supply chain on a real-time basis. Both states found success in establishing their state supply chain management (SCM) system and even track the grain procurement process efficiently. Similarly, Telangana and Uttar Pradesh adopted advanced technologies like GPS and geo-fencing, and have an impressive command center to track trucks carrying food grains. Other states like Assam and Haryana use an SCM designed by the central government, FEAST.

Adopting this system in Assam, however, required several tweaks and customizations. For example, FEAST was incapable of accommodating state-specific needs, which include:

• Multiple stakeholders that operate the state warehouses and consequently require multiple logins;

• Different modes of transportation, such as carts, animals, and boats used to transport food grains in hilly and riverine geographies.

The situation is also unique for states, such as Uttar Pradesh, where the government runs its own mobile-based application to track food grains dispatched from warehouses as adequate IT infrastructure does not yet exist. In Haryana, warehouse digitization has presented difficulties as warehouses are owned by unrelated entities and stock positions continue to be maintained manually. FEAST required customization in Haryana to track grain movements and subsequently generate release orders accurately.

The future of food security in India

Over the next 10 years, TPDS will undergo drastic changes to include:

One Nation One Ration Card: In TPDS, each eligible beneficiary household has a ration card tagged to their home state with which they visit the FPS and pick up the food grains they are entitled to. With the “One Nation One Ration” card initiative, the government intends to introduce an inter-state portability feature through which any NFSA beneficiary can pick-up their ration entitlement from any state regardless of where they reside. This is particularly helpful for migrant populations who leave their home states to earn livelihoods elsewhere. Currently, inter-state portability is active in two sets of states—namely Andhra Pradesh & Telangana and Gujarat & Maharashtra. The government plans a pan-India implementation by June, 2020.

To ensure portability on such a large scale, states will require an automated system that captures demand requirements at every FPS dealers’ location to determine monthly grain allocations. Existing SCMs are not designed to plan for demand based on the uptake at FPS. The states manage the changes to allocations at the shop level manually, based on demand from FPS dealers. This results in a lag in demand and allocation. In the case of Haryana, the state handles demand due to portability through increased allocation to all FPS dealers by 10%. A data-driven system of grain allocation that can manage “one nation one ration card”, therefore, would require significant improvements to the current hardware and software capabilities of state SCMs.

Fortification: The Indian government has been gradually moving from food security toward nutritional security. The government plans to provide fortified rice and wheat that is enriched with essential vitamins and minerals to poor households under the National Food Security Act (NFSA). This requires many changes to the existing TPDS process. Fortification of rice and wheat introduces another step in transportation to the supply chain, where grains would need to move to and from fortification mills, which necessitates additional man-power, cost and time.

Some governments have been experimenting with fortification on a small scale. In 2015, the Haryana State Cooperative Supply & Marketing Federation Limited (HAFED) started a wheat flour fortification program in two blocks of the Ambala district. Under this program, the government provided fortified wheat flour to TPDS beneficiaries instead of wheat kernels to address deficiencies of vitamin B12, folic acid, and iron. For a national-level fortification program to succeed, the existing TPDS would require a re-engineering of processes and systems to absorb the additional requirements of time and resources (labor and cost).

Providing choice to beneficiaries: The Indian government has been experimenting with various models for the transfer of food subsidies. The mode of transfer is either in cash, as in the case of Direct Benefit Transfers in Puducherry, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, and Chandigarh, or in-kind, as with the physical distribution of grains throughout the rest of India. It appears that policymakers prefer the physical distribution of food grains due to existing challenges related to financial inclusion and the unavailability of markets in rural India.

However, MSC believes that beneficiary choice will characterize the future of TPDS. Maharashtra launched a pilot under which NFSA beneficiaries have the option to choose the mode of subsidy transfer, that is, cash or in-kind with an option to revert to the original choice if they are not happy. At the national level, this would demand the management of dynamic data of more than 200 million poor NFSA households on a monthly basis. MSC does not believe TPDS in its current avatar is capable of this feat.

Next steps

The future of TPDS in India is gradually transitioning from one characterized by food security to one of “nutrition security”, which means that the poor will not only have access to food, but essential micronutrients to improve their overall health and nutritional standards. The Indian government has started to take steps to improve the nutritional efficiency of PDS through fortification and through diversification of the food basket. To achieve this and ultimately place more choice in the hands of beneficiaries will require further strengthening and automation of the supply chain, as well as close coordination between states.

A greater emphasis on technology and the development of systems is essential to ensure that states are able to move away from archaic manual processes. Unfortunately, a one-size-fits-all approach to the automation of TPDS is yet to come to a country as diverse as India.