The Government of India (GoI) has done notable work in feeding 115 million children through the Mid-day Meal Scheme (MDMS). It has already made giant strides to reach its first objective of increasing student enrolment and attendance. However, guidelines around the scheme need to improve for the program to reach its second objective of improving the nutrition of the students.

Most decisions regarding MDMS are taken at the national level. However, states play a vital role in the evolution and improvement of the scheme. States have the flexibility to innovate the scheme and the MHRD encourages them to pilot new interventions. States are permitted to use up to 5% of their annual budgets for novel interventions with prior approval from MHRD. Many states have utilized this allotment and further supplemented it with their own funds to achieve a better impact on children’s nutrition and other areas. In the following section, we look at a few examples of such interventions, which we have categorized under infrastructure, nutrition, and monitoring.

Infrastructure

As part of the MDMS, the GoI mandates that all schools have kitchens where meals can be cooked and served fresh to the children.[1] Additionally, the GoI encourages schools to have nutrition gardens[2] as well as toilet and washing facilities.

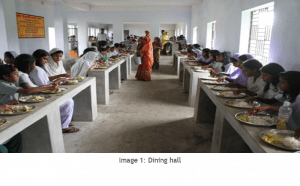

The benefit of the intervention: In schools that lack dining halls, students often have to sit in open spaces on bare floors to eat their meals. Eating in dining halls increases hygiene and makes students more eager to participate in the MDMS.

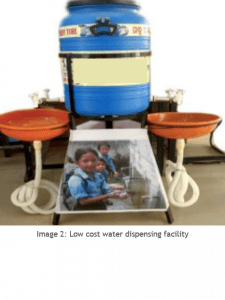

The MHRD advises all schools to have washing facilities but many states cannot afford to construct large enough facilities for school students. Most schools only have one or two taps available as washing facilities. Odisha overcame this problem by installing cost-effective devices made of plastic and rubber with multiple taps running from a tube-well or pipe source, which allows several students to wash their hands at a time.

The benefit of the intervention: This invention saves time, reduces chaos among the children, and increases convenience.

Nutrition

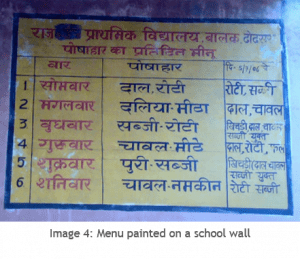

A primary objective of the MDMS is to improve nutrition for children. As India attempts to move from food security to nutrition security, MDMS can emerge as the ideal conduit through which nutritional food can be delivered. Some states have instated policies specifically to utilize the MDMS to improve nutritional outcomes.

In Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Tamil Nadu, governments are piloting fortification[1] of food grains, which are then served as part of the MDM in some districts. The UP government has been fortifying food grains in Varanasi in collaboration with the World Food Program while the Tamil Nadu government is doing it independently.

The benefit of the intervention: The WHO recommends food fortification as a means to reduce malnutrition. By fortifying food grains before serving them to students, the governments of Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh expect to improve the nutritional outcomes of their students.

In Uttarakhand, “apna kitchen, apna bhojan”[2] is organized, under which kitchen helpers teach children to prepare the MDM once a week.

The benefit of the intervention: This teaches students to be responsible for their own food requirements and nutrition while imparting an important life skill for their future.

The Gujarat government has divided the MDM into two meals. As per the guidelines of the MDMS in Gujarat, schools should provide 180 grams of food grains to primary students and 265 grams of food grains to upper primary students. When the requisite food grains are cooked, it expands to a weight that is too much for the primary and upper primary classes to consume at one sitting. Thus, the meal is divided into two meals and served as breakfast and lunch.

The benefit of the intervention: Splitting the meal into two ensures that children eat the complete amount of food grains available. They eat both breakfast and lunch, which ensures that they do not go hungry during the school day.

The benefit of the intervention: Findings of research studies have suggested that MDM has led to increased student retention rates and has played a role in curbing dropouts, especially among girls. By expanding the scheme to Classes 9 and 10, the state governments hope to reap the same benefits.

The benefit of the intervention: The draft of the new education policy of the MHRD states that the morning hours after a nutritious breakfast can be particularly productive. By ensuring that children receive not only a mid-day meal but also an energizing breakfast, the Kerala government makes sure that students are well-fed throughout the school day, which allows them to focus better on their studies.

Monitoring

Monitoring remains an essential component of any scheme. While all states must comply with the National Monitoring Guidelines for MDMS, including monthly and annual report submissions, certain states and union territories have increased the monitoring component on their own.

The benefit of the intervention: This allows authorities to monitor the kitchens in real-time. It also serves to ensure that the kitchens follow all the MDM guidelines and allows mitigation of any untoward incidents, such as instances where children have reported illnesses after consuming the meal in school.

The benefit of the intervention: The rationale behind creating the Maa Samuh is that mothers with children studying in the school will have a greater stake in ensuring that the MDM is prepared in a quality manner.

The benefit of the intervention: This aids in addressing any incidents that may arise from poor quality of food or milk served at the MDM.

General Interventions

Many states have also taken smaller steps to improve their MDM schemes.

References

In the Indian context, “schemes” refer to programs of varying scale, usually undertaken by the government or private bodies

This is not a requirement for those schools whose food is served from centralized kitchen.

Nutrition gardens are vegetable gardens in the school premises. The GoI recommends their use to teach children how to grow their own vegetables.

Fortification is the artificial addition of micronutrients in food. Read more about food grain fortification on MSC’s blog “How India can move from food security to nutrition security”.

In English: “My Kitchen, My Meal.”

The data is available on the MDM website, which posts findings from various research studies

“The biggest impact of COVID-19 on my livelihood is the closure of my primary business. The inter-county travel restrictions and curfews had hurt customer footfall and I was left with no choice but to shut my shop.” Philip, a furniture enterprise owner from Nairobi.

Social and economic disruptions brought about by COVID-19 are projected to contract Kenya’s economy between 1% and 1.5%. As per a World Bank report, since the pandemic struck, two million more people in the country have fallen below the poverty line and around one-third of household-run businesses have not been operating. The Central Bank of Kenya warned that 75% of businesses risk closure due to the lack of emergency funds and crisis in liquidity. Further, a study by BFA on COVID-19 indicates that more than 80% of Kenyan respondents reported a decline in income while 67% reported an increase in expenses. Along with the loss of livelihoods, remittances have fallen while few households have benefitted from direct cash assistance.

In this blog, we present key insights from MSC’s research[1] into the impact of the pandemic on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). We conclude with recommendations for the government to formulate policy measures to support the recovery of Kenyan MSMEs and build their resilience.

Entrepreneurs face declining business revenues and increasing expenses, which have jeopardized the survival of micro and small enterprises

MSMEs play a vital role in the economic development of Kenya. The sector largely comprises micro-enterprises (98.3%)[2] and contributes approximately 40% to the GDP[3]. MSMEs employ 14.9 million people, of whom 12.1 million are employed in microenterprises. However, the sector remains highly informal as only 20% of the 7.4 million MSMEs operate as licensed entities.

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the general economy. Many enterprises have closed and people have lost their jobs. As a result, the purchasing power of consumers is constrained. Consumers spent less on discretionary expenses and limited their consumption to focus on essential goods. While the economy is gradually reopening and the restrictions have been relaxed, the consumers are diffident and have been spending cautiously.

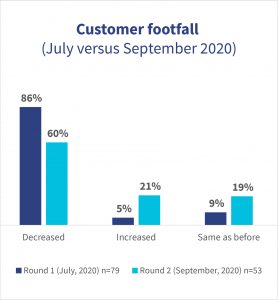

In our two dipstick surveys, we found that most entrepreneurs have struggled with falling business revenues as a result of reduced customer footfall and decreased volume of sales per customer. Furthermore, business expenses increased as travel restrictions hurt supplies and increased prices. Some entrepreneurs who borrowed from financial institutions have found it difficult to repay their loans.

In our two dipstick surveys, we found that most entrepreneurs have struggled with falling business revenues as a result of reduced customer footfall and decreased volume of sales per customer. Furthermore, business expenses increased as travel restrictions hurt supplies and increased prices. Some entrepreneurs who borrowed from financial institutions have found it difficult to repay their loans.

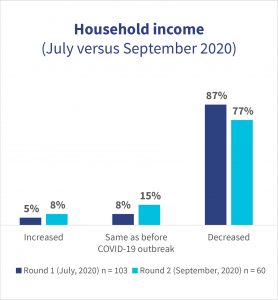

Furthermore, the household incomes of micro and small enterprise owners have generally declined, as members of the household have either lost jobs or seen a lower footfall in their enterprises. However, 32% of entrepreneurs in September, 2020 and 82% of entrepreneurs in July 2020 reported an increase in household expenses.

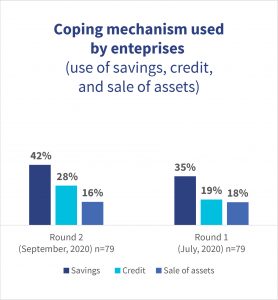

MSMEs operate with limited resources and hence are less able to absorb heightened costs that result from shocks like COVID-19. Most entrepreneurs mentioned that they have exhausted whatever little financial reserves and savings they had. The use and eventual depletion of savings

have increased as many enterprises continue to face a significant decline in income. As a result, only a few entrepreneurs have the resilience to recover after the pandemic, and unless supported, many enterprises will eventually fail to survive the crisis.

have increased as many enterprises continue to face a significant decline in income. As a result, only a few entrepreneurs have the resilience to recover after the pandemic, and unless supported, many enterprises will eventually fail to survive the crisis.

Some entrepreneurs turned to credit and sold off assets to meet household needs but these provided only temporary relief. More female than male respondents reported resorting to the sale of productive assets, especially those based in rural areas and involved in agricultural enterprises. Entrepreneurs who resorted to borrowing reported being trapped in a vicious cycle of repeat borrowing to manage repayments.

A squeeze on credit and limited access to capital has further diminished the ability of enterprises to survive the crisis

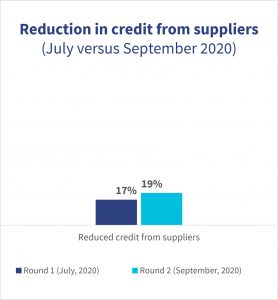

Two specific external sources of capital fueled enterprise value chains before COVID-19. These were loans from financial institutions and the provision of credit from suppliers. The reduction in access to credit from both sources has posed significant challenges for enterprises to maintain business liquidity.

Most financial institutions have reduced their exposure to the MSME segment given its higher levels of vulnerability and lower resilience. Some lenders asked for additional collateral or priced the loans higher than usual, which reflects the higher perceived risk associated with MSMEs. Such conditions have made loans expensive for MSMEs and thus have limited their ability to use additional loans to reestablish business.

Under normal circumstances, suppliers provide goods to entrepreneurs on credit for short terms, usually 15 to 45 days. Yet suppliers have reduced sales on credit. This is because liquidity is crunched in the value chain due to limited funding from financial institutions, a decrease in sales, and increased expenses. Moreover, some enterprises have defaulted on payments to suppliers, which has reduced the ability of suppliers to offer goods on credit to other entrepreneurs. Thus, most entrepreneurs are now forced to make only cash sales to preserve their liquidity and pay suppliers. Hence, they extend credit sales only to their most important customers. This measure has also reduced sales.

Under normal circumstances, suppliers provide goods to entrepreneurs on credit for short terms, usually 15 to 45 days. Yet suppliers have reduced sales on credit. This is because liquidity is crunched in the value chain due to limited funding from financial institutions, a decrease in sales, and increased expenses. Moreover, some enterprises have defaulted on payments to suppliers, which has reduced the ability of suppliers to offer goods on credit to other entrepreneurs. Thus, most entrepreneurs are now forced to make only cash sales to preserve their liquidity and pay suppliers. Hence, they extend credit sales only to their most important customers. This measure has also reduced sales.

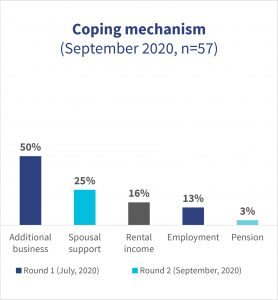

Coping mechanisms by entrepreneurs include diversification of income and businesses

Some entrepreneurs have responded to the risk of business failure by switching their existing products and services to suit the immediate demands of customers. The entrepreneurs who have two or three concurrent businesses have focused on those businesses with stronger cash flows.

Some entrepreneurs have responded to the risk of business failure by switching their existing products and services to suit the immediate demands of customers. The entrepreneurs who have two or three concurrent businesses have focused on those businesses with stronger cash flows.

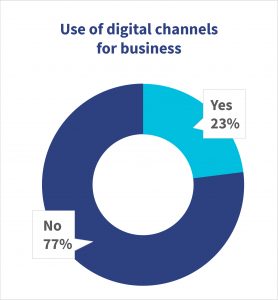

The uptake of digital platforms and technologies by enterprises, particularly micro and small enterprises, has been limited

The pandemic has led to a limited increase in the adoption of digital platforms across urban and rural areas. WhatsApp, Facebook, and other e-commerce platforms provide an opportunity to enhance sales. However, the lack of awareness and understanding to use digital platforms among entrepreneurs have limited the uptake. Among enterprises surveyed in September, 2020, 73% have reported using digital transactions, such as mobile money and electronic bank transfers up from 60% in July 2020.

The pandemic has led to a limited increase in the adoption of digital platforms across urban and rural areas. WhatsApp, Facebook, and other e-commerce platforms provide an opportunity to enhance sales. However, the lack of awareness and understanding to use digital platforms among entrepreneurs have limited the uptake. Among enterprises surveyed in September, 2020, 73% have reported using digital transactions, such as mobile money and electronic bank transfers up from 60% in July 2020.

Recent times saw digital transactions in the country rise, buoyed by the Central Bank of Kenya’s directive that waived the fee on mobile money transactions of less than KES 1,000 (~USD 10) and bank to mobile wallet transfers. While digital merchant payments witnessed a net decline of 16%[4], enterprises in sectors, such as agriculture and food and grocery experienced an upward trend in digital payments.

Measures that the public and private sector can take to support this segment to tide over the crisis

To support the entrepreneurs and enhance their income from their enterprises:

To support the entrepreneurs and reduce the burden of expenses of their enterprises:

To support the entrepreneurs and boost access to finance for their enterprises:

To benefit enterprises in the informal sector:

Enterprises have faced severe disruptions in demand and payment cycles, considering their limited net worth, low backup of savings, and a squeeze on their access to finance. The micro and small enterprises sector needs appropriate responses at all levels to support its recovery in the aftermath of the crisis.

[1] The sample size of the research is, clearly, too small to be representative and therefore the percentages reported throughout should be seen solely as indicative.

[2] KNBS MSME survey 2016

[3] KAM-Focus on SMEs-

[4] FSD Kenya: How COVID-19 has affected digital payments to merchants in Kenya

[5] In April, 2020, the CBK suspended listing of negative information of borrowers on the Credit Reference Bureau by commercial banks. This was to cushion borrowers who were unable to repay their loans due to the effects of the pandemic, such as job loss or disruption in business. The CBK however, lifted the suspension in October, 2020 due to rising loan defaults that affected the financial sector.

In India, 115.9 million children from vulnerable segments receive cooked meals every school day through the Mid-day Meal Scheme (MDMS). The MDMS is the flagship school-based meal program of the Government of India (GoI). It started in 1925 in Madras (now Chennai) to end classroom hunger. The scheme has a twofold objective of increasing student enrolment and attendance while improving nutrition. Since then, the MDMS has evolved in terms of coverage, benefits, and implementation. Today, it counts among one of the more successful programs of the GoI.

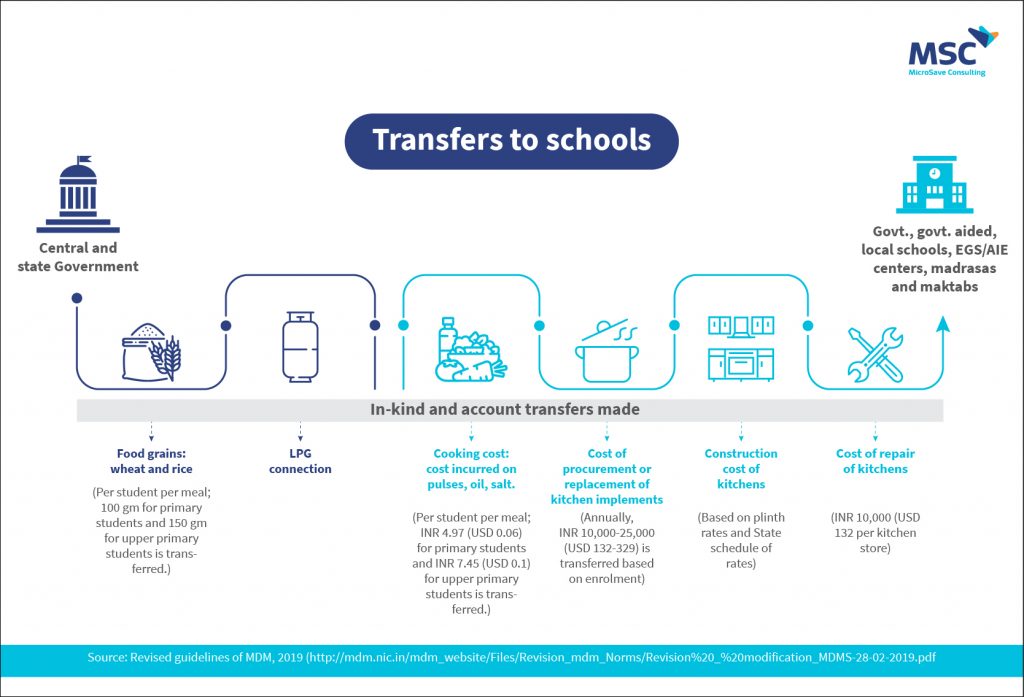

The MDMS covers all primary and upper primary students (classes 1-8) who study in government and government-aided schools, and EGS or AIE centers including madrasas and maktabs. Children in primary classes receive 450 calories and 12 grams of protein per meal, while upper primary children receive 700 calories and 20 grams of protein.

MDMS is a centrally sponsored scheme (CSS). Two committees at the national level, the Empowered Committee under the Ministry of Human Resources and Development (MHRD) and the Steering and Monitoring Committee, under the Department of School Education and Literacy, administer the MDMS. These committees are responsible for the overall direction of the MDMS, including program design, components, budget allocations, and monitoring process.

The MDMS has many components. Most are delivered to the schools as highlighted in the following graphic. The government provides food grains in the form of wheat and rice alongside LPG connections to schools. It also makes several transfers to bank accounts to reimburse schools for costs associated with cooking, procurement, or replacement of kitchen implements, and construction or repair of school kitchens.

Kitchen helpers cook and serve the meals to the children. The national mandate instructs that kitchen helper receive an honorarium of INR 1,000 (USD 14) per month deposited directly into their bank accounts. States are also permitted to top up these amounts. For instance, Kerala pays each kitchen helper INR 9,000 (USD 118) per month while Tamil Nadu pays them INR 10,083 (USD 133) per month. Additionally, students have started receiving a Food Security Allowance if their school cannot provide MDM daily.

The state governments also receive a fee for monitoring, management, and evaluation (MME) from the central government. The state-level committees use this transfer to ensure adequate monitoring by the district- and village-level committees and run digital monitoring mechanisms, such as the Automatic Monitoring System and Management Information System.

Most components of the MDMS were revised in 2019 when the government released new policy guidelines for MDMS and added additional components. This is evident in the increased allocation for MDMS in the Union Budgets. The budget allocation increased from INR 99 (USD 1.3) billion in 2018-19 to INR 121 (USD 1.59) billion in 2019-20 and INR 110 (USD 1.47) billion in 2020-21. In 2018-19, 90% of the funds available for MDMS were utilized.

The MDMS has capitalized on the improvements in digital infrastructure in India to incorporate an Automatic Monitoring System (AMS) and Management Information System (MIS). Both are used to monitor the scheme in real-time. The AMS allows schools to report the number of children that avail the MDMS each day. This facilitates monitoring and follow-up at the state or district level at no cost to the schools. Under the AMS, states have set up different systems for data collection, which includes Interactive Voice Response Systems (IVRS), SMS, mobile applications, or web applications. The data is aggregated at the state level in a predefined format and is uploaded to the MIS on a real-time basis. The MIS portal captures information on several important parameters of MDMS on both a monthly and annual basis.

Evidence shows that MDMS has had a positive impact on enrolment, and increased attendance and retention rates of students. According to some reports, students who receive MDM have shown a significant increase in classroom attention. This affirms that MDMS is well on its way to achieving its first objective of larger attendance and enrolment. However, it remains a long way from achieving its second goal of improving nutrition, as current practices have proven short of having any significant nutritional impact. There is a need for innovation and ideation on novel methods to improve MDMS. Work is already underway on this. Many Indian states have incorporated new interventions as state guidelines that have been furthering the impact of the MDMS are not only improving nutrition but also enhancing other areas.

References

Data taken from the MDMS website as of the year 2018-19.

This is equivalent to grades 1 to 8 in the American Education System.

Education Guarantee Scheme/ Alternative and Innovative Education Centers

CSS are implemented by state governments. The central government, however, is the larger funder while states fund a smaller share. In the case of MDMS, the fund sharing ratio is 60:40.

The graphic highlights each of the components transferred to schools from the government. The quantum of each is also mentioned. Read more about plinth rates here.

LPG is Liquefied Petroleum Gas used for cooking.

We have assumed a conversion rate of USD 1 = INR 75.

Food security allowance is not a novel concept but has never been used before 2020. The first time the GoI is using it is at a time when schools have been shut since March, 2020 due to COVID-19. The state governments have been asked to transfer the food security allowance to the children.

These parameters include category-wise enrolment, details of the teachers, details of the kitchen-helpers with social composition, availability of infrastructural facilities, such as kitchen stores and kitchen implements, mode of cooking, drinking water, and toilet facilities.

The agriculture sector, the largest employer in the world, has been devastated by COVID-19. The measures taken by countries to curb the spread of COVID-19 have disrupted both demand and supply of agricultural products globally, particularly in developing countries where agriculture is labor-intensive. Although most countries designate agriculture as an essential service and exempt it from the restrictions in movement, the shift in demand from commercial to households coupled with the limited availability of logistical services has hit the sector hard.

Women are the backbone of agriculture and play a vital role in the local retail market, particularly in Africa. The outbreak of the pandemic further restricted their mobility, which was already low. They had to struggle to sell their produce and procure agricultural inputs.

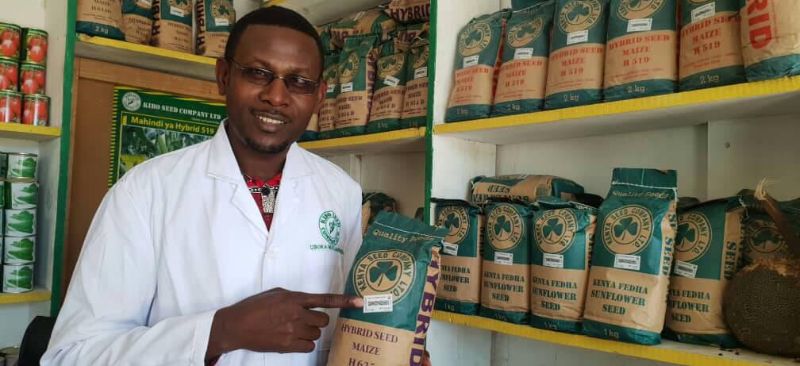

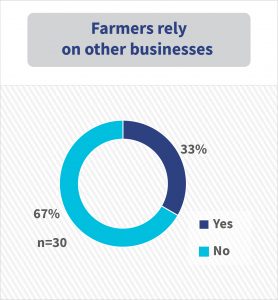

As a result of COVID-19, farmers in Kenya now face several concerns and challenges. MSC carried out a dipstick study to understand the level of constraints the sector faces, how the government has been supporting the sector with relief measures, and what more needs to be done to help the sector recover.

Reduced income and the rising cost of cultivation has made farmers in Kenya more vulnerable

Agriculture dominates the economy of Kenya and employs more than 70% of the workforce. Agriculture contributes USD 1.37 billion in annual exports . The global lockdown has hurt Kenyan agriculture exports due to restrictions on the movement of goods. A study done by COLECAP indicates that Kenya’s agricultural industry suffers a loss of roughly USD 3 million every day during COVID-19 lockdowns.

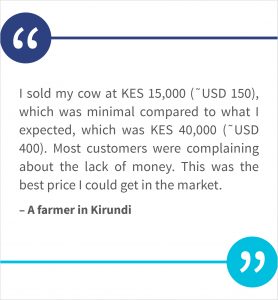

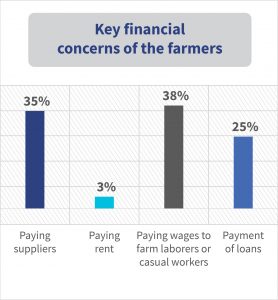

The pandemic led to a significant decline in household income. The unavailability of agricultural input materials and uncertainty about the marketing of the products has reduced production. Farmers who produce perishable goods like horticulture and floriculture outputs could not sell their products and incurred losses. At least 45% of farmers have seen their household income fall.[1] Other sources of income like poultry and livestock could not help them much due to a substantial drop in demand

Subsequent relaxations of restrictions have improved sales, but demand remains low. The cost of transportation also remains high along with the high cost to procure raw materials. A study by the research firm 60_decibles reports that 71% of farmers paid a higher price for the inputs between June and October, 2020. Even the rent of land has increased by 27%. To cope with these rises, farmers have been cutting down on the cultivated areas—which will ultimately, make them more vulnerable.

Subsequent relaxations of restrictions have improved sales, but demand remains low. The cost of transportation also remains high along with the high cost to procure raw materials. A study by the research firm 60_decibles reports that 71% of farmers paid a higher price for the inputs between June and October, 2020. Even the rent of land has increased by 27%. To cope with these rises, farmers have been cutting down on the cultivated areas—which will ultimately, make them more vulnerable.

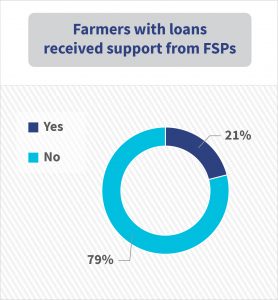

The burden of loan repayment and reduced options to borrow have further complicated the challenges in liquidity that farmers face. Among the farmers in the survey, 47% had accessed loans after the pandemic while others were unable to access loans due to rigorous rules and conditions, particularly around collateral. They had to opt for credit from informal sources.

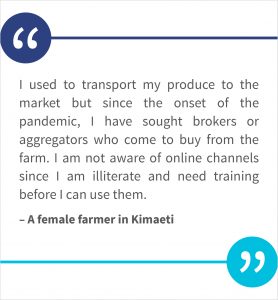

Digital technologies could provide solutions to some of the issues that face farmers, especially those related to access to markets and credit. However, the uptake of these technologies and platforms is limited among farmers. Only 40% of those surveyed have a smartphone and only 13% used digital agriculture extension services. Lack of awareness and sound digital literacy, financial constraints, and limited digital capability are key factors that led to low uptake.

Digital technologies could provide solutions to some of the issues that face farmers, especially those related to access to markets and credit. However, the uptake of these technologies and platforms is limited among farmers. Only 40% of those surveyed have a smartphone and only 13% used digital agriculture extension services. Lack of awareness and sound digital literacy, financial constraints, and limited digital capability are key factors that led to low uptake.

Farmers have used the combination of coping mechanisms during the pandemic

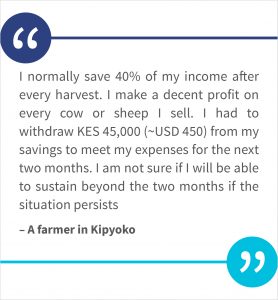

Among the farmers surveyed, 60% relied on savings during the pandemic to meet their household expenses. Many farmers are worried as they exhausted most of the savings during this period and urgently need access to alternative solutions. Farmers usually save in the form of productive assets and sell them when they need money. They did the same during the pandemic, but could not get the right price due to low demand as even the buyers now have lower purchasing power—see “Recovery and survival of micro and small enterprises in Kenya in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic”.

Digital credit provided some relief to many farmers helping them smoothen consumption. Farmers have also continued to rely on family and social networks to provide support to manage household expenses.

One-third of the farmers surveyed devised additional ways to increase their income by diversifying the sources, especially those who were producing perishable goods. Most of them have relied on existing businesses or other activities like day labor or working on other farms. These additional sources provided them some extra earnings. Laying off agricultural labor is also a common coping mechanism for farmers, which has further enhanced the vulnerability of typically poorer agricultural laborers.

One-third of the farmers surveyed devised additional ways to increase their income by diversifying the sources, especially those who were producing perishable goods. Most of them have relied on existing businesses or other activities like day labor or working on other farms. These additional sources provided them some extra earnings. Laying off agricultural labor is also a common coping mechanism for farmers, which has further enhanced the vulnerability of typically poorer agricultural laborers.

The government of Kenya has extended its support to the farmers

In May 2020, the Government of Kenya has announced a stimulus package of USD 503 million to support the sectors hit by the coronavirus pandemic. It covered eight areas including agriculture.[1] Of the USD 503 million, the government channeled USD 30 million for the supply of farm inputs to cushion 200,000 small-scale farmers in 12 counties across the country in the first phase.

At the time of reporting, the e-voucher program is being implemented in partnership with Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB) and Safaricom. The objective of the program is to reduce pilferage and promote the purchase of farm inputs by farmers. Small scale farmers with five acres of land or less are eligible for support in the form of an e-voucher worth USD 200 per acre. The government also allocated USD 15 million to assist horticultural and flower producers to continue accessing international markets.

The Ministry of Agriculture laid out protocols and guidelines at the onset of the pandemic to minimize interruptions within the food supply chain. These include:

Farmers need additional support to restore agricultural activities and reduce vulnerabilities

Increase the outreach of government programs

In India, for instance, the technology platform Haqdarshak has built a repository of welfare programs and matches citizen profiles with welfare program eligibility. This enables prospective applicants to receive a customized list of eligible schemes. Haqdarshak works with the government, NGOs, and village-level entrepreneurs and has channeled benefits worth INR 1 billion (USD 13.67 million) to 296,100 beneficiaries. In Kenya, digital learning platforms, such as Arifu have used interactive SMS to provide training on good agricultural practices and financial literacy. Such platforms can be used to raise awareness among farmers on agriculture schemes. Further, radio and other electronic media campaigns should be tapped for effective coverage. Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture and Kilimo Media International (KIMI), for example, have used radio to provide agricultural extension services for smallholder farmers.

Access to the market for agricultural products

Agricultural finance

The government and private agencies can support financial institutions with loan guarantee funds. In 2008, IFAD and AGRA provided USD 5 million as a 10% first loss guarantee to Equity Bank to disburse USD 50 million in agricultural loans to farmers with little or no collateral[1]. Equity Bank developed “Kilimo Biashara,” an agricultural financing product designed to make funding available and affordable to small-scale farmers. Similar initiatives are required to help farmers in accessing credit during the pandemic. Moreover, donors or the government or both can extend support to financial service providers to design farmer-friendly financial products and services.

The crisis brought about by the pandemic has highlighted the persistent issues that ail the agriculture sector of Kenya and forced government and non-government organizations to develop systems and institutions to better prepare farmers to respond to adverse situations like COVID-19. Even during the crisis, some success stories have emerged that demonstrate the resilience of local agriculture and food systems that could be replicated by the government and private agencies in other parts of the country.

One such example is the Utoma Youth Group of Makori and Homa Bay counties. The group’s agri-business suffered due to the inter-county travel restrictions. However, the members soon shifted their focus to local markets. The members harvested the crops in morning and afternoon shifts and individually delivered the produce to the households complying with the safety measures of maintaining social distance and using personal protective kits. Youth who lost their jobs and returned to the village also volunteered to work in the fields and sell the grains and vegetables locally along with other group members. While the group still faces a financial crunch because of the lower prices that they can realize in the local market compared to the market in Nairobi, it has managed to keep business afloat.

These measures could harness the natural entrepreneurial resilience of Kenyan farmers, and enable them to bounce back from the setbacks and hardships arising from the pandemic. Indeed, the crisis could be an important catalyst for the reform and restructuring of agricultural and agri-finance markets in Kenya.

[1] Working paper: Credit guarantee schemes for agricultural development, The World Bank and Agriculture Finance Support Facility

[1] BORGEN Magazine

[2] The sample size is, clearly, too small to be representative and therefore the percentages throughout this blog should be seen as

indicative.

[3] Government of Kenya; Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperative; others

[4] Working paper: Credit guarantee schemes for agricultural development, The World Bank and Agriculture Finance Support

Facility