The Department of Financial Services (DFS) in the Ministry of Finance, MicroSave, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation designed a survey to understand the coverage and quality of Bank Mitrs across a sample of SSAs; and to understand customers’ experience with PMJDY. The study was conducted in November and December 2014 across 41 districts in 9 states. A total of 2,039 BM locations and 8,789 beneficiaries were surveyed. BMs were assessed on dimensions such as availability based on the physical address and contact details provided to DFS by banks, transaction-readiness and branding. The customers were asked questions about their experience on aspects such as first bank account under PMJDY, receipt of RuPaycard and availability of Aadhaar and its linkage in PMJDY account. 69% of Bank Mitrs were physically present at the stated location, 48% were transaction ready and 11% were untraceable. 86% of PMJDY account holders reported that this was their first bank account and 18 % have received Rupay card.

Blog

RuPay Sparklin – Do not delete

RuPay offers various benefits

In our previous blog in this series, we presented recent trends in the fintech space in India. In that blog, we also defined the low- and middle-income (LMI) segments and examined the challenges that fintechs and investors face in catering to these segments.

RuPay cards issues against total number

On 26th March 2012, National Payment Corporation of India (NPCI) launched Rupay – India’s own payment gateway network. ‘RuPay’ is a low-cost alternative to other payment gateways, such as MasterCard and VISA. Banks pay lower transaction processing fees as transactions are performed on the domestic payment network. This makes RuPay a viable digital payment solution for the rural, low, and middle-income segments in India. RuPay offers various benefits to its cardholders, such as cash-back on utility bills and ticket bookings, in-built accidental insurance cover, and online payments across e-commerce portals.

To read our report on the fintech landscape in India, click here

To know more about the Financial Inclusion Lab and to apply, click here

Will India be better now?

NPCI has established a domestic payment gateway to turn RuPay into a fully functional card. The payment gateway, ‘RuPay PaySecure’, has been promoted as a solution for various e-commerce portals in India. The gateway aims to nudge domestic consumers to make digital payments. The government provided important support to the RuPay card by bundling it with Basic Savings Bank Deposit Accounts (BSBDAs) opened under the national financial inclusion programme Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY). Various stakeholders we interacted with in this research suggested that irrespective of the challenges pertaining to the LMI market, it offers huge potential. These stakeholders include investors, fintechs, and incumbents. Most of them, however, have been taking a cautious approach and waiting to see a proven business model before venturing into this space. A 2017 Deloitte report suggests that in the medium term, fintech players will consolidate their position in urban areas and metro cities, and will extend to the rural and semi-urban space over next 3-5 years.

Challenges on the demand-side

Low awareness among customers

Customers are unaware that:

- They are eligible to apply for a RuPay card in the first place; this lack of awareness thus reduces penetration of RuPay cards;

- The RuPay card PIN becomes invalid after 45 days4 if the card is not used within this period after initial activation;

- A RuPay debit card comes with an in-built accidental cover of INR 100,000 (1424.8 USD)5 . However, to keep the insurance cover in-force, the cardholder needs to carry out at least one transaction every 45 days.6 Customers are largely unaware of this add-on benefit and the associated conditions – thus also reducing the potential use of RuPay cards.

Challenges on the supply-side:

Non-distribution of RuPay cards or PINs by BMs:

- BMs do not receive RuPay card or PINs within stipulated 7-8 working days from the bank branch to which they are linked.

- BMs are unable to inform customers to collect their RuPay cards or PINs. Their phone is either switched off, not reachable or is invalid.

- Some bank branch managers are reluctant to encourage applications for RuPay cards as they fear that cards held by illiterate customers may lead to fraud.

Consumer Protection in the Digital Age

Why does consumer protection matter?

In November 2017, in Can Fintech Really Deliver On Its Promise For Financial Inclusion?, we noted, “It is quite clear that till date, the regulatory environment and consumer protection provisions remain too weak to secure the poor. Many have already lost money in basic money transfer transactions. Millions are negatively listed on credit reference bureaus (CRB) and in the databases of large banks because of digital credit. Furthermore, in the flagship M-PESA deployment, almost half of non-airtime top-up transactions are for gambling … With a track record like this, how can we honestly claim that technology is helping the poor?”

The problems with digital credit persist and continue to grow alarmingly. We were told by the CEO of one of the Kenyan CRBs that the number of negatively listed borrowers has grown from 2.7 million in March 2017 to around 3.6 million (about 13% of the adult population of the country) 14 months later. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that a worrying proportion of digital consumer credit loans are used to finance the sports betting epidemic that is sweeping the continent. Perhaps, as a result, a recent analysis noted that borrowers default on a third of first cycle loans and are negatively listed on the CRB. Some of the negatively listed loans are alleged to have been taken out without the knowledge or permission of the owner of the mobile phone and mobile money account.

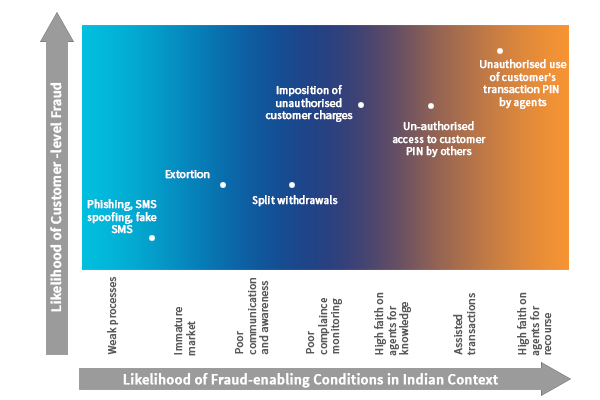

MicroSave has repeatedly highlighted the risk associated with digital financial services (DFS), particularly in rural areas, with high levels of orality (illiteracy and innumeracy). Across Asia and Africa, we have seen agents open accounts with the same PINs for all users – and thus almost all DFS users in a village have 1234 or 5555 as their PIN. While agents do this to facilitate the agent-assisted transactions that oral people so often seek, it presents tremendous opportunities for a variety of fraudulent behaviours.

Without protection, there is no trust

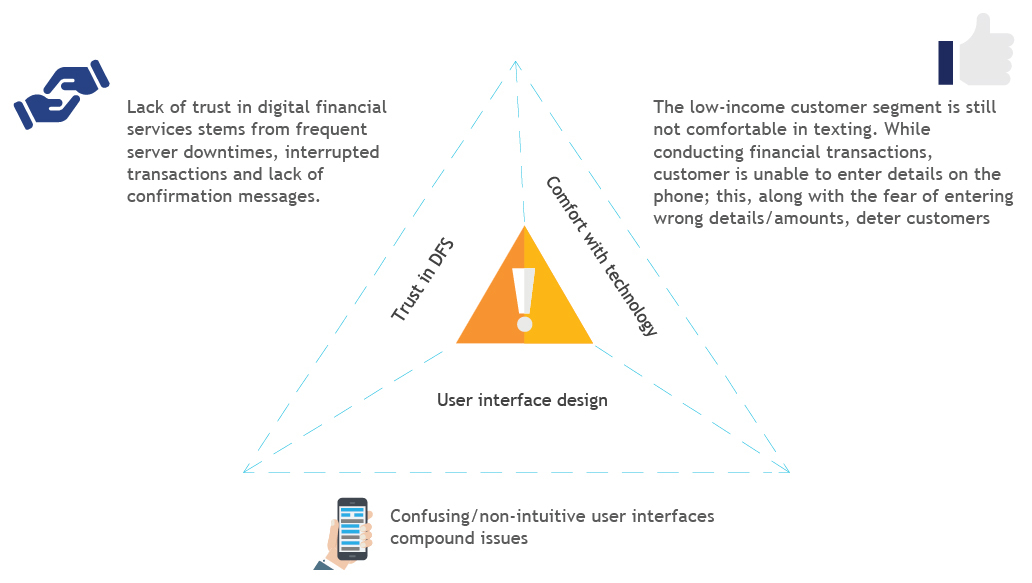

The frail consumer protection measures in place amplify a trinity of debilitating factors that prevent millions from signing up for DFS and still less from using it. Many people, particularly those who are “oral” and struggle to read the text and understand number strings, are simply uncomfortable with technology and live in fear of making mistakes that risk losing them money. User interfaces remain a mystery for millions across the globe – and so they either seek agent assistance or avoid DFS entirely. These first two factors further increase the alarmingly prevalent lack of trust in DFS across many countries, which we examined in A Question of Trust – Mitigating Customer Risk in Digital Financial Services.

“We keep hearing mobile money users complain about unstable network, delayed service, missing money and many other negative comments about mobile money. Why then should we register for these services?” – A non-user in Uganda

This lack of trust is not without valid basis. In Connecting the Dots: Putting Risk, Customer Protection, and Financial Capability in Perspective, we examined the risks that consumers faced in an emerging DFS market like India in 2015 – before the concerns around the national digital identity Aadhaar were really understood. As with Bangladesh, Philippines, and Uganda, most of the risks identified in this consumer-focused research were operational in nature and could be resolved relatively easily. However, the results of these risks – service denial and potential fraud, particularly in an environment with limited financial capability and high level of trust in agents – is potentially dangerous.

In the words of a recent report from Dvara Trust, “Most people had experienced fraud (especially via phone impersonators), and did not know how to protect themselves or seek redressal they want a humanized redressal system to be in place that is affordable, trustworthy, responsive, and effective.” Is that an unreasonable expectation?

Realised or not, the fear of losing money by sending it to the wrong number remains a very real problem in many markets. Indeed this fear encourages people to ask agents to conduct transactions on their behalf and is, therefore, an important driver of the growth of OTC transactions. The current customer recourse systems – both through call centres and at offices – which are often viewed as difficult to access, poorly trained and often unable to resolve problems.

Customers with substantive problems most commonly call customer care when they have transferred money to the wrong number. DFS providers have consistently struggled with repudiation (see “Fraud in Mobile Financial Services”, page 23), and have typically adopted a policy of “repudiation only with the consent of both parties”. As a result, customer care typically can do little to help customers resolve this issue. However, clearly defined and well-communicated policies on repudiation and free calls to better-trained customer care centres can do much to improve this.

Similarly, people want to know what they are signing up for – particularly when it involves financial services. We have seen with digital credit, users, who often use feature phones, are directed to the Internet to find the terms and conditions that govern their loans. And, if they are able to do so, they face pages and pages of dense legal language. Unsurprisingly, borrowers do not always comprehend what they were agreeing to and overlook important clauses regularly. The opaque communication of terms and conditions further undermines trust. Indeed Rafe Mazer has demonstrated that including a high-level summary of key terms and conditions in the loan application screens reduces default rates by 9%.

Data privacy matters

It is clear our industry needs to address concerns around data privacy. This is in addition to enhancing consumer protection against fraud and ensuring better access to both services and grievance mechanisms. The ‘privacy paradox’, where people say they care about privacy but are ready to relinquish it to access services, has led to the convenient assumption that poor people are not concerned with privacy.

However, the recent work by Dvara Trust has comprehensively disproved the assumption. It noted: “People value privacy for itself. People cared so deeply about their personal data such as photos, messages, or browsing history that at times they did not want to share it even with trusted family members. In instances where consumers were sharing data, they wanted providers to seek their consent prior to data collection and wanted a guarantee that no harm would come to them through any malicious use of their data.”

The Indian Supreme Court, while affirming the fundamental right to privacy for all Indians, quotes Richard Posner to explain the ‘privacy paradox’ “that as long as people do not expect that the details of their health, intimacies and finances among others will be used to harm them in interaction with other people, they are content to reveal those details when they derive benefits from the revelation.”

As we noted in How Smart are Smartphone Lending Apps in Kenya? “Some apps require detailed, and what appears to be irrelevant or intrusive, information on sign-up; this has raised concerns among users and may hinder take-up. For example, users may be asked to upload their pictures or share access to their private data, including call records, SMS, airtime loading history, handset device details, GPS, and social media.” Abusing data privacy is also likely to erode the trust – as Silicon Valley providers are learning – albeit too slowly.

The regulatory response

The regulatory response has been diverse in the developed world. While the USA adopted laissez-faire regulations, Europe mandated a higher standard of protection. The recently introduced General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the EU Directive of 1995 (which the GDPR replaces), and OECD’s Privacy Guidelines have collectively led to convergence on international data protection laws. Graham Greenleaf notes that non-European jurisdictions with data protection laws converge on at least half of the higher principles mandated in Europe since the 1990s. However, developing countries like India have just started to respond to the challenges related to data protection, with the Government of India appointing an Expert Committee to draft a Data Protection White Paper. But globally, there is a long way to go.

The scourge of predatory digital consumer lending needs an immediate response in a growing number of countries before it destroys the market for ethical lenders. Yet ultimately, regulators will need to introduce significantly stronger consumer protection and data privacy measures if the full benefits of the digital revolution are to be fully realised. These regulations should also recognise the unique characteristics of the Internet and shun protectionism that can raise the cost of accessing services and reduce productivity. These regulations will need to pay particular attention to the more vulnerable members of the population, particularly those who either do not understand the technology or are “oral” or both. Louise Malady’s “Consumer Protection Issues for Digital Financial Services in Emerging Markets” provides a good overview of the issues and possible regulatory responses.

So let us ask again, “does consumer protection matter?”

The impact of this erosion of trust is plain to see. The GSMA’s State of the Industry Report for 2017 highlights the success of East Africa, where 66% of adults use mobile money services. However, it also describes how uptake still lags outside a few countries. The report highlights how usage among those who have enrolled is well below the levels needed to create sustainable digital ecosystems.

Of the much-celebrated 690 million DFS accounts that were opened, only 168 million (24%) are 30-day active. Each of those inactive accounts cost significant resources to open and maintain – and these costs must be borne by those who are active if the provider has to break-even. Small wonder that DFS services remain considerably more expensive than is desirable ‒ and often acceptable for consumers – thus further depressing their usage.

Where is my teacher?

In the past decade, India has made huge strides in improving access to education. Government initiatives like the Right to Education Act (2009) and Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (now Samagra Shiksha), have definitely increased enrolment. The number of government schools has also gone up over the years.

But what is the status of public education in the county? Is providing the access enough? Is the quality of learning sufficient to equip children with the skill sets necessary to succeed?

Our publication talks about the primary problem plaguing the system and discusses a few innovative solutions to help improve the situation of public education in the country.

Implementing digital transformation

This video describes what digital transformation is and gives us steps on how financial institutions should go about implementing it. It touches on digitising processes, products and business models, channels as well as engagement and user experience.[br]

Equity bank’s digital transformation – Video

There has been a confusion around the business case for digital transformation. Most financial institutions think of it as a cost. The business case anchors on increased revenues, lower costs, and enhanced significance. The video looks at a case study of how Equity Bank has over the years transformed from a brick and motor bank to a digital bank and the support that MicroSave has offered through this process.