There is a key difference in how the Digital Financial Services (DFS) market in India has evolved when compared to other countries. While in most countries the expansion of DFS along with agent networks has been driven by profit, the growth of DFS in India has essentially been the result of government mandates. The mandates have certainly:

- demonstrated India’s commitment to financial inclusion;

- propelled the growth of the agent network in geography and scale by pushing banks to participate in DFS thus facilitating physical access to finance; and

- focused product offering to account opening.

To understand the landscape of DFS in India, we must first understand these government initiatives that have shaped it. As the landscape continues to develop, it is extremely important that we understand how this prescriptive foundation is likely to influence the character of DFS’ development.

Over the years, the Government of India has facilitated financial access by promoting account opening through various programs such as the Swabhimaan scheme. Launched in 2011, the scheme aimed to bring access to banking facilities to all villages in the country with a population of 2,000 or more by March 2012 with the target to reach 74,000 villages primarily through DFS enabled transaction agents. The PMJDY programme launched in 2014 expanded the previous financial inclusion mandates with the target to open an additional 50,000 agent locations, and as of August 2015, 177 million accounts had been opened under the scheme.

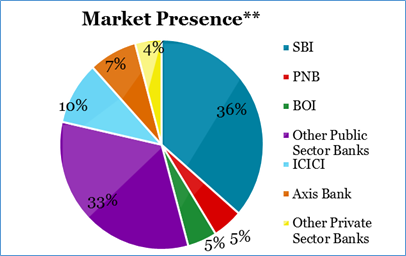

Figure 1 Market Presence of Major Banks in India

**Agent market presence is defined as the proportion of cash-in/cash-out (CICO) agents serving each provider. Numbers here are provided on a till basis not on the outlet level. Hence, if an agent serves three providers, it is counted three times. This method therefore discounts smaller exclusive networks. The seven providers with the highest market presence are presented in this pie chart, with the categories ‘public sector banks’ and ‘other private sector banks’ consisting of a number of banks that have a market presence of less than 4% each.

The Helix Institute’s Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) survey in India, conducted between January and March 2015, interviewed 2,682 agents across 14 states and provides supporting data on the extent to which the DFS market is led by government players. The research on market presence of DFS providers (Figure 1) illustrates that Government owned public sector banks, led by the State Bank of India, account for 79% of all agents surveyed, with an even higher presence in rural areas—88% of rural agents are linked to public sector banks. This is because the government has placed a disproportionately large emphasis on public sector banks to establish agents relative to the private sector banks, so that the big public sector banks such as SBI and BOI have a lot of agents which are concentrated in rural areas, versus the big private sector banks like ICIC and HDFC which have much lower agent market presence and are more focused on urban areas.

The ANA India research shows agents conduct a median of 13 transactions per day, which is the second lowest across all ANA research countries. However, this was primarily driven by account opening under the Government’s PMJDY programme, which was well under way and being promoted during ANA data collection. As a result the programme inflated the number of transactions. In fact, PMJDY alone accounts for 38% of reported transactions and when PMJDY figures are removed from transaction levels, agent daily transaction volumes decrease to a median of 10 a day. Therefore, the government’s account opening programme is propping up the volume of transactions, and without it another driver will have to take its place to drive higher volumes.

.png)

Figure 2 Agent Median Daily Transactions and Monthly Profits across ANA Countries

Note: Profitability as shown in the Figure is calculated as earnings – operating expenses for all countries. In the case of India, the fixed monthly component given to agents has also been considered in this calculation. This is different from other ANA countries where commissions earned makes up the total earnings of the agent. The profits reported in India are at an outlet level as opposed to other countries where they are at a provider level.

Hence, the ANA data shows us that the number of agents in India, their reach out into rural areas, and the volumes of transactions they are doing are all largely driven by top-down government policy. The Brookings Institution’s 2015 Financial and Digital Inclusion Report and Scorecard ranks the Indian government number one is the world for the work it has done to extend this access to finance. However, now that this initial infrastructure has been laid, the important question is: will the government have to continue pushing it, or will the private sector now pick-up where the government has left off and provide a business case for agents to continue being agents? Further, the Government and Intermedia data show that about half the accounts opened are not active, meaning that the extension of access that the government drove still has not translated very efficiently into usage of these systems.

New important payments bank legislation has just been approved to allow a set of eleven diverse players to now try their hand at digital financial services. Their task will be to ensure that agents are busy and provide a high level of customer service to Indians seeking digital financial solutions. Our next blog analyses the ANA data to give these payment bank licensees some practical advice as to where they should start if they are to achieve this goal.

a. Users are “number literate”

a. Users are “number literate” d. Users do not prefer “unrelated” clubbing

d. Users do not prefer “unrelated” clubbing

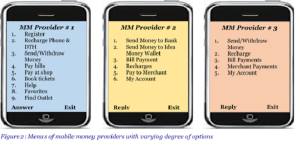

requires more navigation for exploring sub-menu options (see figure 2).

requires more navigation for exploring sub-menu options (see figure 2).