With the renewed interest in client-centricity, it seems appropriate to recall the core role of customer service in serving the low-income market. In our research, MicroSave consistently sees “how I am treated by the staff (or agents) of the institution” in the top 3-4 drivers of customer choice of a service provider as well as uptake and use of financial services.

This is not surprising: there are five compelling reasons why excellent customer service must be a “prime directive” for any market-led financial institution:

- Good service keeps customers.

- Good service builds word-of-mouth business.

- Good service can help you overcome competitive disadvantages.

- Good service is easier than many parts of your business.

- Good service helps you work more efficiently.

But contrary to common perception, customer service is much more than teaching your front-line staff to smile. Customer service depends on a wide range of variables, including:

- Culture of customer service – created and delivered by staff throughout the organization as a living value.

- Product/service range – not only the core products and services offered but also the additional services (such as customer rewards and incentives).

- Customer knowledge to anticipate and meet customers’ needs and expectations to retain and grow the customer base through customer relationship management.

- Delivery systems need to be efficient, effective, responsive and reliable: mass services are typified by limited contact time and a product rather than service focus.

- Service delivery environment in terms of the location of agents and branches, their opening hours, their physical layout and design, as well as the atmosphere – space, color, lighting, temperature, maintenance, etc. – in the outlets.

- Technology is often integral to a product – for example, mobile wallets or mapped accounts, links to ATMs or card-based savings accounts and increasingly access to automatic, algorithm-based credit.

- Employees’ role in customer care cannot be overstated – employee relationship management and staff incentive schemes can play a key role to optimize this key component of customer service.

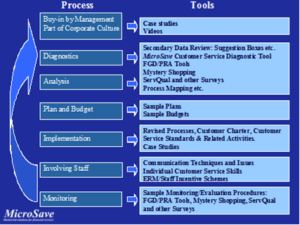

Diagnosis to Drive Customer Service

There are always hundreds of steps that a financial institution could take to improve customer service, the challenge is to identify which steps it should take. As part of the on-going service improvement process, financial institutions should analyze the high impact, low-cost steps available in order to identify the “quick wins”. MicroSave’s approach to customer service involves using a variety of market research tools to examine the perceptions and priorities of the clients and staff, as well as a comprehensive diagnostic and analysis tool built around the “8Ps” of marketing: Product, Price, Place, Promotion, People, Process, Physical evidence and Position. The diagnostic tool is administered to senior management and frontline staff over a period of two days during which they assess the frequency and impact of occurrence of a series of customer service related issues within the “8Ps” framework … and analyze the optimal response to these.

Central to the truly effective customer service is knowledge of the customer and his/her needs and expectations. MicroSave’s market research toolkit provides a good basis for assessing these needs and several of the core tools in the toolkit have been modified to support customer service. Many financial institutions are implementing data warehouses to optimize the way they use the information they collect on their clients – this will allow them to predict customer needs, define service expectations, focus direct marketing efforts and begin to cross-sell a range of their products to their clients.

Process Optimisation

There is a growing recognition that some financial institutions have not paid adequate attention to optimizing the processes used to deliver their products and services to their clients. The basic procedure used to analyze and improve delivery processes is broadly:

- Set and monitor performance targets for activities and processes.

- Be alert for signs of stress such as lengthening queues, decreasing numbers of new customers, falling activity rates, longer working hours for staff, increasing customer complaints, increased agent churn, etc.

- Look for lost-cost, quick wins such as minor adjustments to procedures to save processing time, re-refining job descriptions or adjustments to physical infrastructure.

- Improve your sources of information by using client satisfaction surveys, customer exit surveys and serviced suggestion boxes or through internal/external evaluations.

Study existing processes, through process mapping or activity-based costing.

Process mapping involves the detailed analysis and recording of systems and procedures in the form of a flowchart to identify inefficient or redundant procedures and to optimize the risk/efficiency trade-offs.

Technology

With the growth of technology-based opportunities to enhance service standards and delivery processes, technology has to be an important part of any forward-thinking financial institution’s strategy. Financial institutions should therefore not only constantly examine options for technology-based solutions, but also subject them all to rigorous cost/benefit and risk analysis. Furthermore, in many countries – particularly in rural areas, infrastructure issues need careful assessment since unreliable electrical supplies, high levels of dust or problems with availability of spare parts or rapid-response maintenance capability can turn a technology-based dream into a nightmare.

That said, effective computerization can significantly increase the speed and efficiency of processing transactions and of generating financial reports and management information. By introducing Bidii, a card-based system to replace the old passbook, Kenya Post Office Savings Bank was able to reduce the cost of processing salary deposits by 58% and withdrawals by 36%. The saving in teller-client interface time also meant that KPOSB could double the number of clients it served without increasing the congestion in the banking halls.

To help employees meet and exceed the service expectations of customers, the financial institution should set customer service standards. Service standards are measures against which actual performance can be judged. Staff must understand what management wants them to do and how often they want them to do it, it is therefore essential to:

- Spell out your institution’s service policy.

- Establish measurable criteria and set standards.

- Specify and prioritize actions you want employees to take in response to customers.

- Recognize employees who exceed customer service standards.

- Involve customers in providing feedback.

Customer service standards in financial service organizations typically involve a mixture of quantifiable factors and less quantifiable factors. Quantifiable factors might include speed/efficiency of service (although it is important to note issues of centralized vs. de-centralized decision making and how these affect speed/efficiency) and knowledge of products, systems and procedures etc. Less quantifiable factors include staff members’ professional appearance, friendliness, and attitude – ah those smiles!

Ultimately, however, performance must be assessed through customer satisfaction analysis involving both existing clients and exiting or past clients. This analysis is aimed at testing performance and identifying opportunities for innovation, and requires both qualitative and quantitative primary research using focus group discussions, mystery shopping and quantitative surveys such as ServQual questionnaires.

We know, for example, that in 2013 Kenya Safaricom tried to persuade M-PESA agents to hold more liquidity by increasing commission rates on higher value transactions. When this had little/ no impact on agents’ liquidity holdings, Safaricom returned to their original approach of saturating the market with agents. This allows customers seeking to conduct larger transactions to either go to the larger agents that hold bigger liquidity pools (for example those of

We know, for example, that in 2013 Kenya Safaricom tried to persuade M-PESA agents to hold more liquidity by increasing commission rates on higher value transactions. When this had little/ no impact on agents’ liquidity holdings, Safaricom returned to their original approach of saturating the market with agents. This allows customers seeking to conduct larger transactions to either go to the larger agents that hold bigger liquidity pools (for example those of