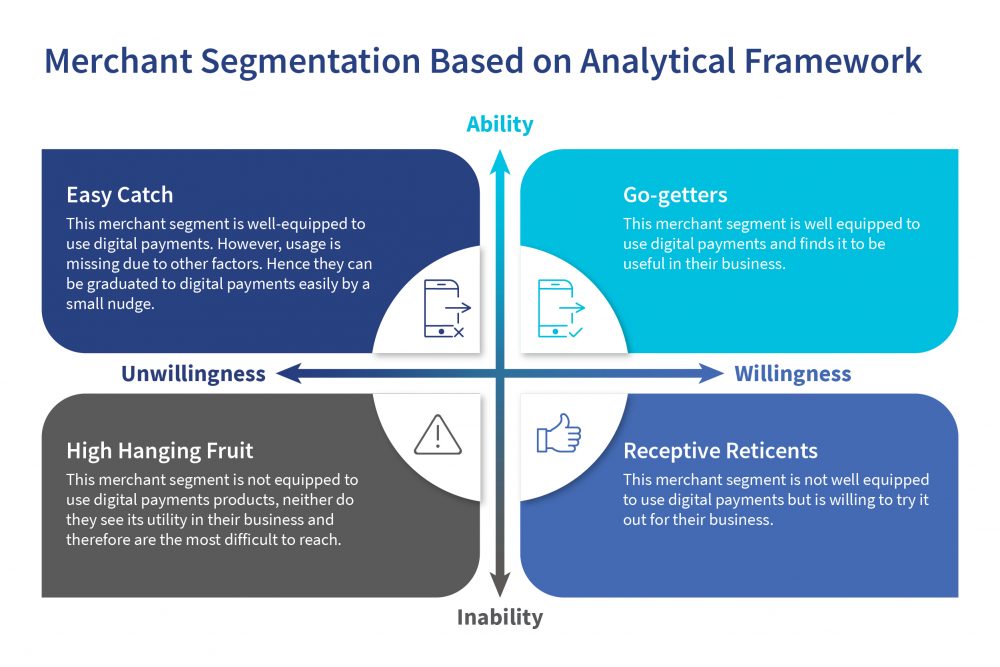

This is the third blog of the “Digitizing merchant payments in India” series. In the first blog, we discussed the potential of merchant ecosystem in India and the need to design distinct solutions for them. In the second blog, we described the characteristics of the first two merchant personas—the go-getters and the receptive reticents. In this third blog, we discuss the remaining two personas of the merchant ecosystem: a) The high-hanging fruits and b) The easy-catch merchants.

The High-Hanging Fruits

Pushpa Kumari owns a small grocery shop in Terna village of Varanasi district of Uttar Pradesh, India. She has two school-going children and is the sole earning member of her family. She is educated up to Class 3 and has been managing the business since her husband’s demise seven years back. Pushpa does not read newspapers or watch television due to a lack of time. With a footfall of around 40-50 customers per day, Pushpa earns INR 6,000 (USD 86) per month, which is just enough to meet her daily expenses. She makes sales in cash and uses the same to make payments to her suppliers. She does not trust digital payments and does not intend to use them. Moreover, other merchants in her village also accept payments only in cash.

What makes her a high-hanging fruit?

What makes her a high-hanging fruit?

This category of merchants believes in carrying out the current transaction at hand. They are not too concerned about customers’ payment needs and preferences. They have not used digital payments so far and have heard negative things about them. Their limited literacy level also makes them uninterested in accepting digital payments. (Behavioral traits: Skeptics and cognitive misers)

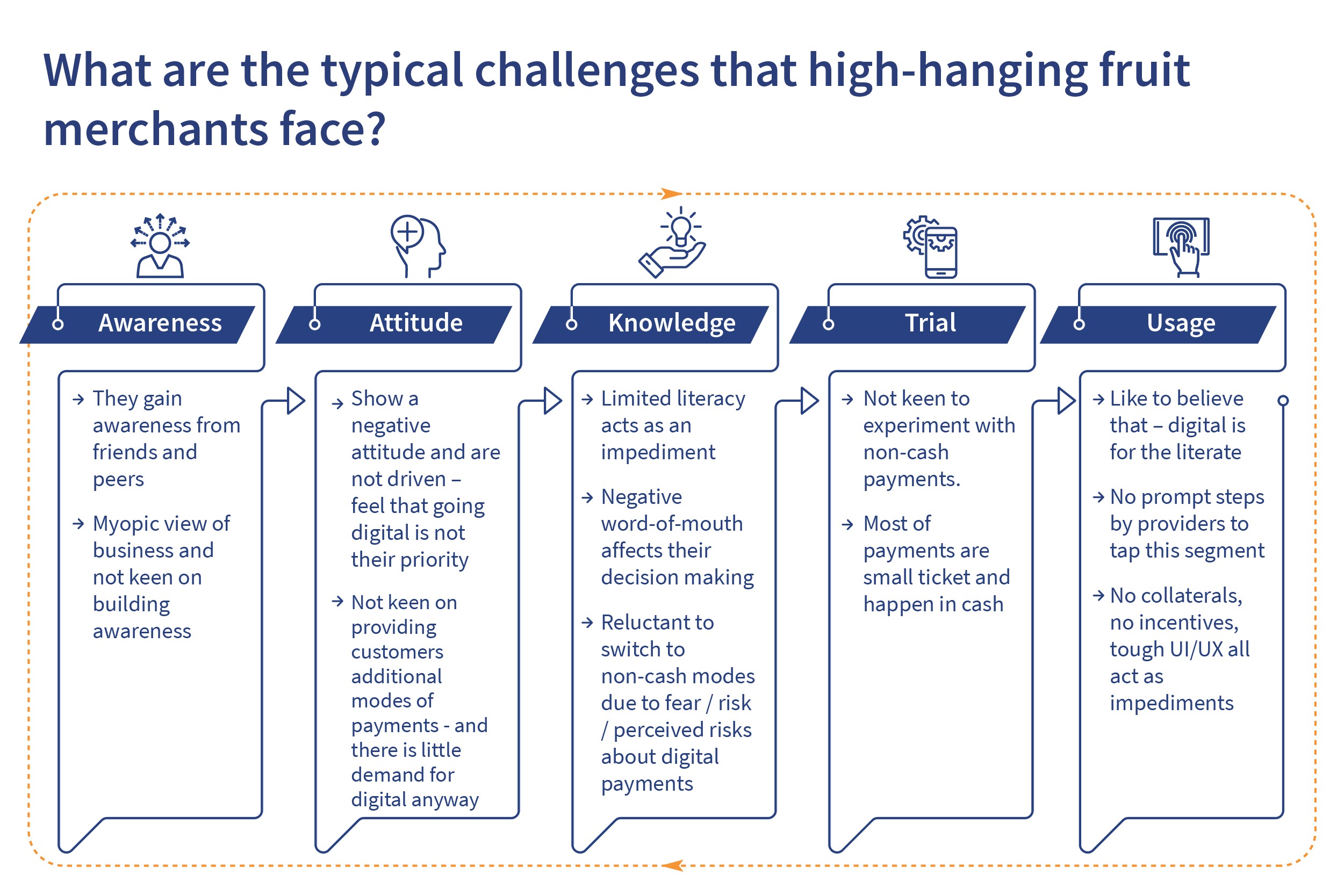

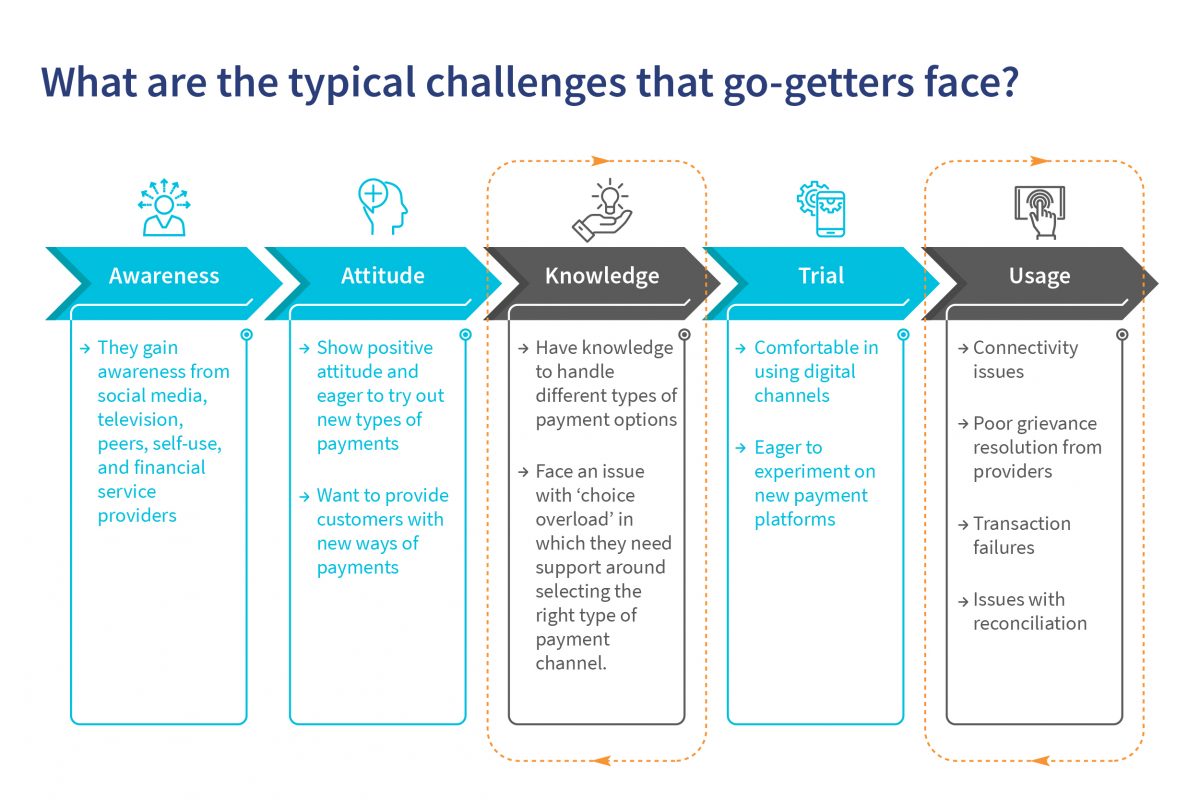

What are the typical challenges that high-hanging fruit merchants face?

High-hanging fruit merchants, by nature, are not very ambitious about their business. They have no great ambition to grow their businesses (or revenues), and hence, they would never need digital channels. Also, they want physical evidence; so they prefer cash as they can see and touch it. This makes them highly reluctant to switch to newer modes of payments. Plus, they are greatly influenced by their local community, which has a strong affinity for cash. Most of their acquaintances and suppliers accept or demand payments in cash. This makes them feel that cash is the best and easiest way of doing business. In several cases, they also belong to the oral segment (illiterate and semi-literate) and this segment exhibits different characteristics compared to the literate segment. (Refer to our pitch-book on the mobile wallet for Oral—MoWo mobile wallet design.)

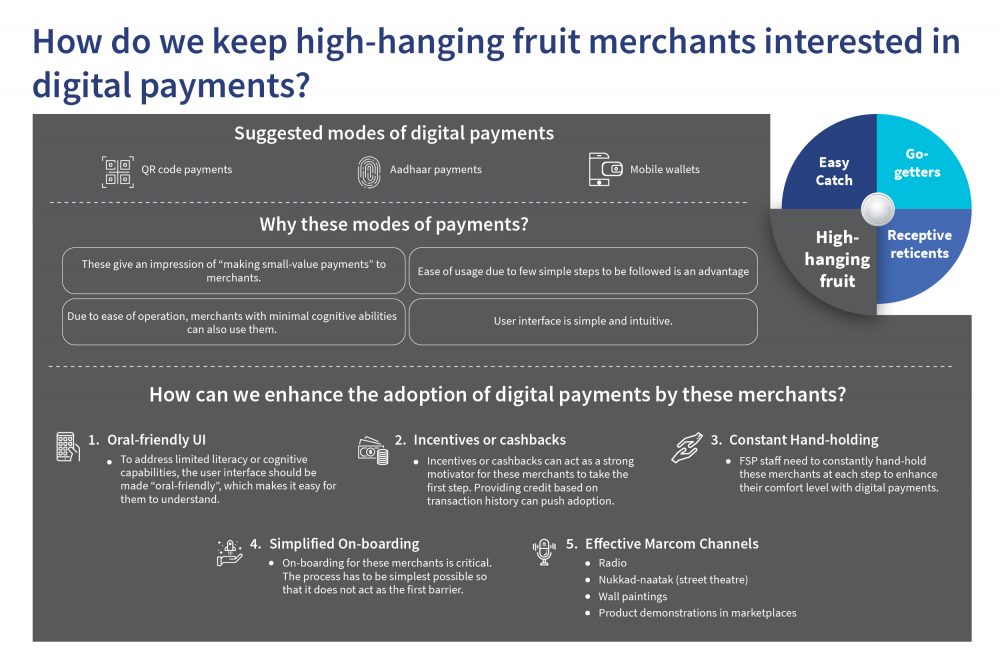

How do we keep high-hanging fruit merchants interested in digital payments?

Typically, merchants belonging to this category operate in locations where digital payments are not common. These merchants need simple-to-use payment acceptance options such as QR Code, Aadhaar-based payments (like BHIM Aadhaar) and mobile wallets so that customers who approach them can easily make payments. These modes help reduce reliance on cash and also build customer confidence to spend money electronically.

While developing digital financial products and services for this segment of merchants (who are predominantly oral), service providers need to customize their interfaces to accommodate oral habits and practices. The user interfaces need to be developed keeping in mind the cognitive usability constraints of these oral merchant segments.

Some of the ways in which high-hanging merchants can be digitally included are discussed in the image below:

The easy-catch merchants

The easy-catch merchants

Shailendra Shinde, a 35-year-old graduate, owns a cosmetics shop in J.M. Road of Pune. He has a bank account as well as an ATM-cum-debit card for personal use. While every other big or small merchant on the street has a Paytm, Mastercard or VISA sticker prominently displayed at their outlets, surprisingly, his shop is the only exception. Our curiosity took us to Shailendra. He clarified that he subscribed to Paytm during demonetisation (November 2016) and used it for a few months. After some time, he removed the Paytm barcode collateral from the main counter and hid it. These days, only when he is sure that a customer does not have cash, he presents the option of paying through Paytm. Nonetheless, almost 50% of his customers ask him to let them pay through Paytm on a daily basis. The money collected using Paytm is mostly used by Shailendra for bill payments and recharges.

On asking if he is losing his customers due to non-acceptance of Paytm, he replied that the value of each transaction at his outlet is small. The customers always have that amount of change and hence, he does not need to accept payments through Paytm. On an everyday basis, about 100 customers visit Shailendra’s outlet and he makes daily sales of INR 15,000 (USD 210). He added that to pay using Paytm, a customer needs to take out the phone, open the app, enter an amount, and then pay. During peak hours, neither he nor customers have the time to make payment through Paytm. A simpler and quicker way at this time is to use cash. Shailendra also said that occasionally, in these peak hours, some customers leave without paying, under cover of the crowd. Overall, he sees using Paytm to collect payments as a hassle. Also another issue which bothers him is the issue of taxation. He is not comfortable with the fact that by going digital, he will be ‘exposing’ his income to the tax authorities. He is also apprehensive about the security aspects of digital payments (though he has no experience to date).

What makes him an easy-catch merchant?

These merchants are well-versed with the use of digital payments but are unwilling to go digital. They are very smart and can quickly gauge the digital options available with them to decide which one could work for them (and in some cases even make this decision without using them). For them the priority is to carry on business safely and securely even if it means sacrificing on customer loyalty. Hence despite having digital payments channels available, they prefer to collect cash payments from their customers. (Behavioral traits: Status quo and choice overload)

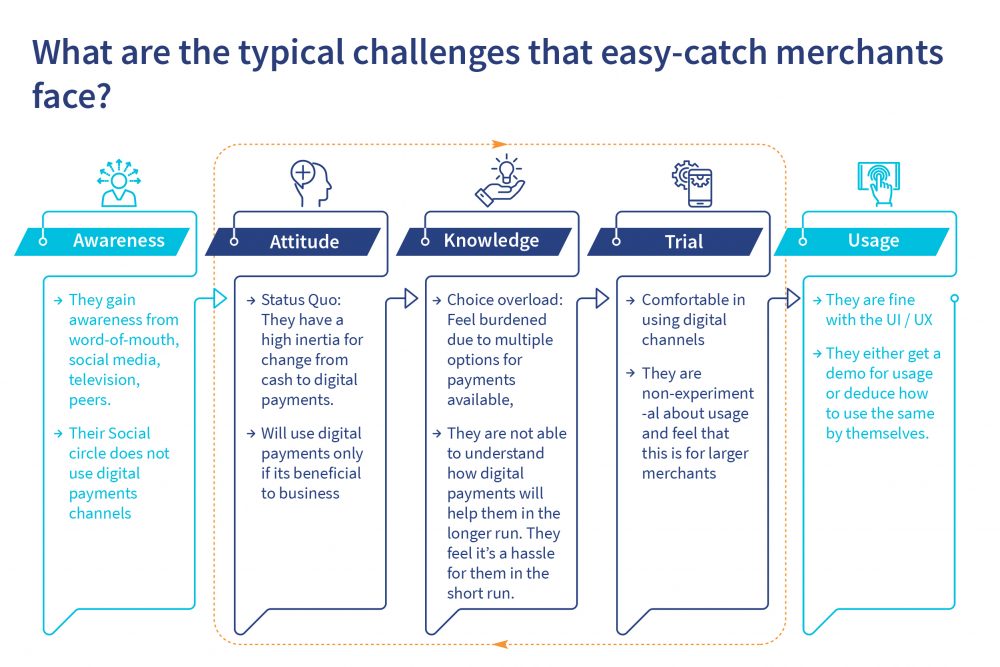

What are the typical challenges that easy-catch merchants face?

The easy-catch merchants have the ability to use digital payment channels but are unwilling to do so for various reasons.

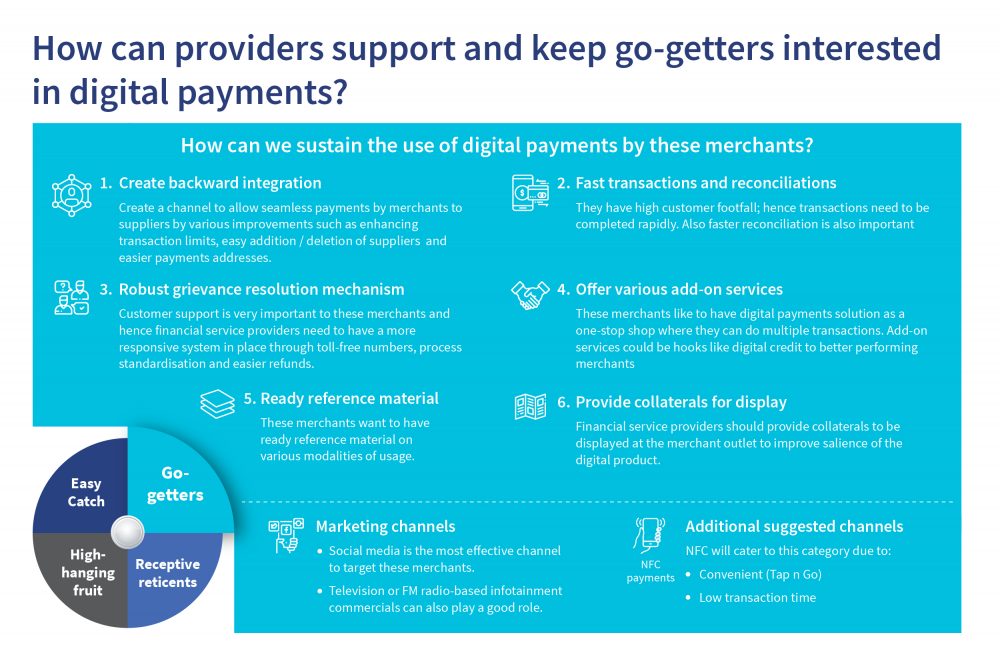

How do we keep easy-catch merchants interested in digital payments?

Easy-catch merchants are fairly well-educated and are well-versed in digital technology. They are highly cynical when it comes to trusting the digital payment service providers and hold on to any negative experiences for a long period of time. Some of the ways using which easy-catch merchants can be on-boarded to digital payment modes are discussed in the image below:

Conclusion

Our research notes that providers need to create ‘hooks’ to enable them on-board the various categories of merchants. Some of these which are important to enhance adoption of digital payments are:

• Digital credit: A majority of small-time merchants rely on informal mechanisms to meet their credit requirements. Service providers can use their transaction data to provide or facilitate digital credit to these merchants.

• Simple UI: In the current environment, with plenty of available apps and solutions, merchants would need support in the form of easy-to-use apps, which could also target the ‘oral segment’ of merchants.

• Grievance redress mechanism: A robust and effective grievance redress mechanism—on which the merchants can fall back on in cases of transaction errors, transaction reversals, reconciliation or any other queries—would be of utmost importance.

What makes him a receptive reticent?

What makes him a receptive reticent?

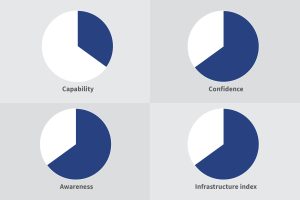

Sanjay, Deepak, Pushpa, and Shailendra are merchants in different parts of India who sell goods from their own shops. They interact and transact with a variety of customers on a regular basis. To a varying degree, all four share a few common traits. They feel that digital payments are good for them. All of them have experienced banking and used financial services at different levels. They show a willingness and capacity to become offline merchants and join the digital bandwagon.

Sanjay, Deepak, Pushpa, and Shailendra are merchants in different parts of India who sell goods from their own shops. They interact and transact with a variety of customers on a regular basis. To a varying degree, all four share a few common traits. They feel that digital payments are good for them. All of them have experienced banking and used financial services at different levels. They show a willingness and capacity to become offline merchants and join the digital bandwagon.