The digital finance industry is both young and dynamic, and as it grows, it is constantly innovating to address the issues it faces. One of the key contemporary issues is over the counter (OTC) transactions. The delivery of mobile money over the counter raises a number of questions since it can: 1) limit product and ecosystem evolution; 2) decrease provider profitability; and 3) lead to unregistered transactions, which run the risk of money laundering and terrorism financing. This report explores these questions and, with the help of data from the Helix Institute, InterMedia, and the Groupe Spécial Mobile Association (GSMA), provides an analytical perspective on the pros and cons of the OTC to arrive at conclusions and key considerations which move the industry forward. This report was first released by The International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

Blog

High-Hanging Fruit and Easy Catch—Merchants who need additional “hooks” and hand-holding

This is the third blog of the “Digitizing merchant payments in India” series. In the first blog, we discussed the potential of merchant ecosystem in India and the need to design distinct solutions for them. In the second blog, we described the characteristics of the first two merchant personas—the go-getters and the receptive reticents. In this third blog, we discuss the remaining two personas of the merchant ecosystem: a) The high-hanging fruits and b) The easy-catch merchants.

The High-Hanging Fruits

Pushpa Kumari owns a small grocery shop in Terna village of Varanasi district of Uttar Pradesh, India. She has two school-going children and is the sole earning member of her family. She is educated up to Class 3 and has been managing the business since her husband’s demise seven years back. Pushpa does not read newspapers or watch television due to a lack of time. With a footfall of around 40-50 customers per day, Pushpa earns INR 6,000 (USD 86) per month, which is just enough to meet her daily expenses. She makes sales in cash and uses the same to make payments to her suppliers. She does not trust digital payments and does not intend to use them. Moreover, other merchants in her village also accept payments only in cash.

What makes her a high-hanging fruit?

What makes her a high-hanging fruit?

This category of merchants believes in carrying out the current transaction at hand. They are not too concerned about customers’ payment needs and preferences. They have not used digital payments so far and have heard negative things about them. Their limited literacy level also makes them uninterested in accepting digital payments. (Behavioral traits: Skeptics and cognitive misers)

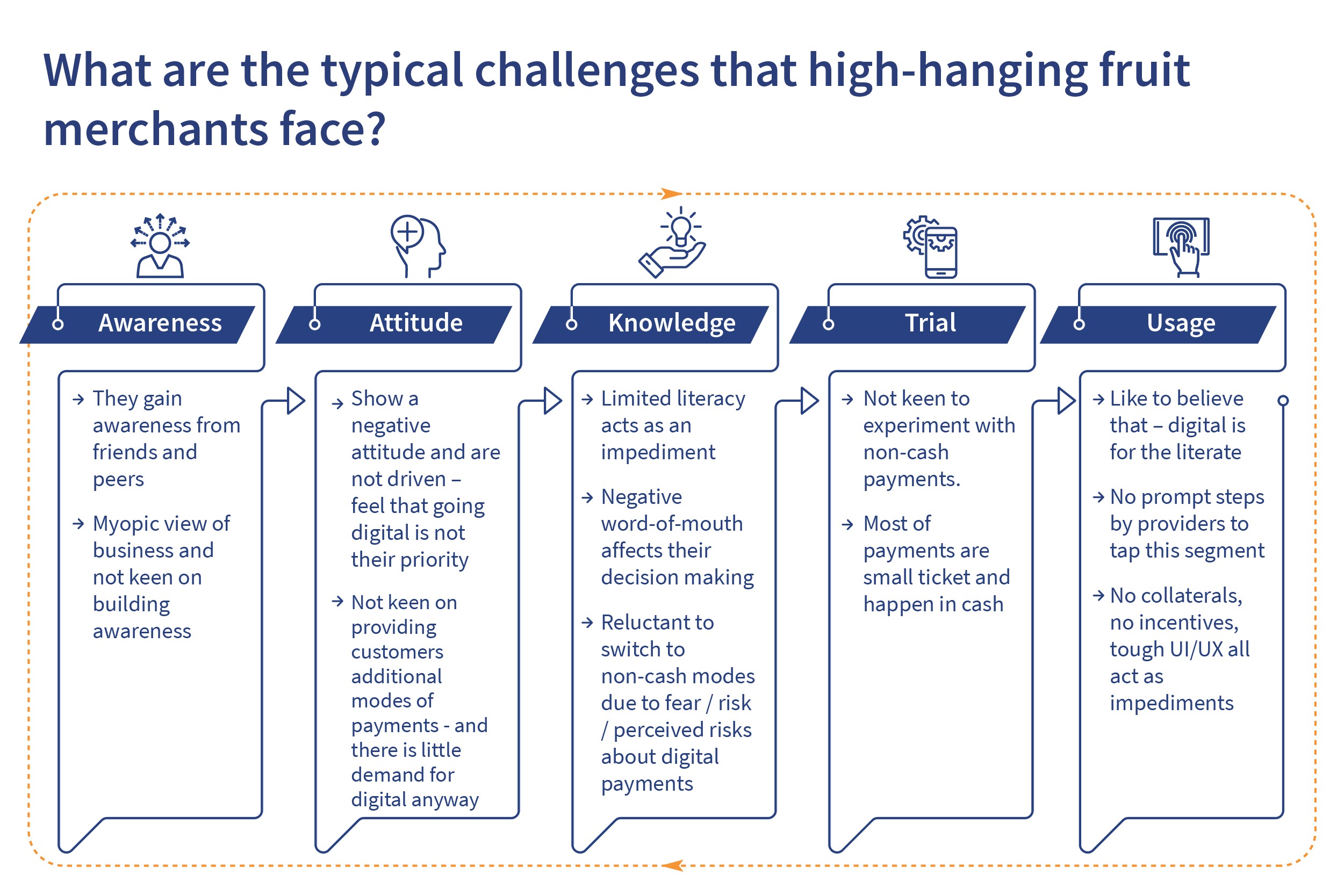

What are the typical challenges that high-hanging fruit merchants face?

High-hanging fruit merchants, by nature, are not very ambitious about their business. They have no great ambition to grow their businesses (or revenues), and hence, they would never need digital channels. Also, they want physical evidence; so they prefer cash as they can see and touch it. This makes them highly reluctant to switch to newer modes of payments. Plus, they are greatly influenced by their local community, which has a strong affinity for cash. Most of their acquaintances and suppliers accept or demand payments in cash. This makes them feel that cash is the best and easiest way of doing business. In several cases, they also belong to the oral segment (illiterate and semi-literate) and this segment exhibits different characteristics compared to the literate segment. (Refer to our pitch-book on the mobile wallet for Oral—MoWo mobile wallet design.)

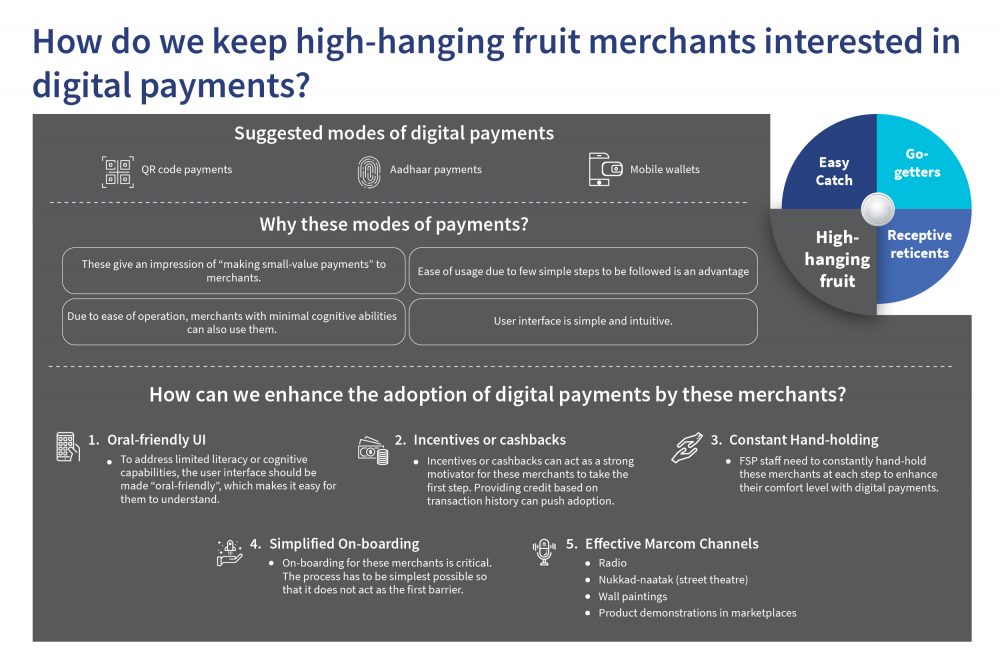

How do we keep high-hanging fruit merchants interested in digital payments?

Typically, merchants belonging to this category operate in locations where digital payments are not common. These merchants need simple-to-use payment acceptance options such as QR Code, Aadhaar-based payments (like BHIM Aadhaar) and mobile wallets so that customers who approach them can easily make payments. These modes help reduce reliance on cash and also build customer confidence to spend money electronically.

While developing digital financial products and services for this segment of merchants (who are predominantly oral), service providers need to customize their interfaces to accommodate oral habits and practices. The user interfaces need to be developed keeping in mind the cognitive usability constraints of these oral merchant segments.

Some of the ways in which high-hanging merchants can be digitally included are discussed in the image below:

The easy-catch merchants

The easy-catch merchants

Shailendra Shinde, a 35-year-old graduate, owns a cosmetics shop in J.M. Road of Pune. He has a bank account as well as an ATM-cum-debit card for personal use. While every other big or small merchant on the street has a Paytm, Mastercard or VISA sticker prominently displayed at their outlets, surprisingly, his shop is the only exception. Our curiosity took us to Shailendra. He clarified that he subscribed to Paytm during demonetisation (November 2016) and used it for a few months. After some time, he removed the Paytm barcode collateral from the main counter and hid it. These days, only when he is sure that a customer does not have cash, he presents the option of paying through Paytm. Nonetheless, almost 50% of his customers ask him to let them pay through Paytm on a daily basis. The money collected using Paytm is mostly used by Shailendra for bill payments and recharges.

On asking if he is losing his customers due to non-acceptance of Paytm, he replied that the value of each transaction at his outlet is small. The customers always have that amount of change and hence, he does not need to accept payments through Paytm. On an everyday basis, about 100 customers visit Shailendra’s outlet and he makes daily sales of INR 15,000 (USD 210). He added that to pay using Paytm, a customer needs to take out the phone, open the app, enter an amount, and then pay. During peak hours, neither he nor customers have the time to make payment through Paytm. A simpler and quicker way at this time is to use cash. Shailendra also said that occasionally, in these peak hours, some customers leave without paying, under cover of the crowd. Overall, he sees using Paytm to collect payments as a hassle. Also another issue which bothers him is the issue of taxation. He is not comfortable with the fact that by going digital, he will be ‘exposing’ his income to the tax authorities. He is also apprehensive about the security aspects of digital payments (though he has no experience to date).

What makes him an easy-catch merchant?

These merchants are well-versed with the use of digital payments but are unwilling to go digital. They are very smart and can quickly gauge the digital options available with them to decide which one could work for them (and in some cases even make this decision without using them). For them the priority is to carry on business safely and securely even if it means sacrificing on customer loyalty. Hence despite having digital payments channels available, they prefer to collect cash payments from their customers. (Behavioral traits: Status quo and choice overload)

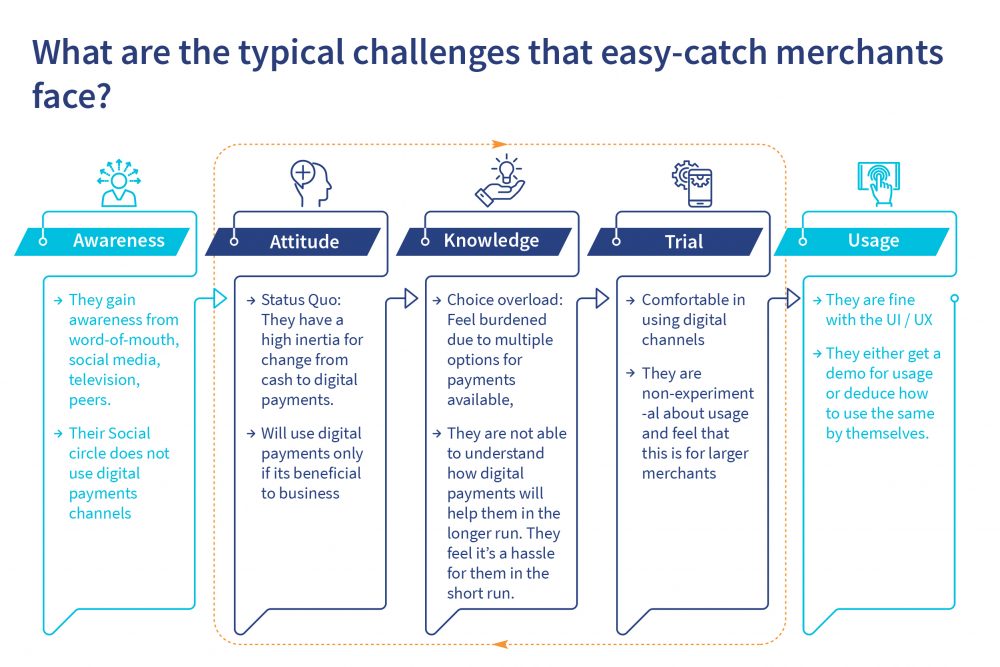

What are the typical challenges that easy-catch merchants face?

The easy-catch merchants have the ability to use digital payment channels but are unwilling to do so for various reasons.

How do we keep easy-catch merchants interested in digital payments?

Easy-catch merchants are fairly well-educated and are well-versed in digital technology. They are highly cynical when it comes to trusting the digital payment service providers and hold on to any negative experiences for a long period of time. Some of the ways using which easy-catch merchants can be on-boarded to digital payment modes are discussed in the image below:

Conclusion

Our research notes that providers need to create ‘hooks’ to enable them on-board the various categories of merchants. Some of these which are important to enhance adoption of digital payments are:

• Digital credit: A majority of small-time merchants rely on informal mechanisms to meet their credit requirements. Service providers can use their transaction data to provide or facilitate digital credit to these merchants.

• Simple UI: In the current environment, with plenty of available apps and solutions, merchants would need support in the form of easy-to-use apps, which could also target the ‘oral segment’ of merchants.

• Grievance redress mechanism: A robust and effective grievance redress mechanism—on which the merchants can fall back on in cases of transaction errors, transaction reversals, reconciliation or any other queries—would be of utmost importance.

The potential of merchant payments in Cote d’Ivoire: What is the situation in the informal sector?

Merchant payments has been a top priority for digital financial service providers in 2018. However, the activity rates of acceptor merchants and customers remain low, according to GSMA’s report on the mobile money industry. The adoption of merchant payments in Côte d’Ivoire has been limited, where two mobile phone operators, MTN and Orange, dominate the market.

In November, 2017, MicroSave Consulting (MSC) conducted a diagnostic study on the success factors of merchant payments solutions using e-wallets. We conducted the study with 93 accepting merchants, which revealed that only 5% of payments are made via the merchant solution.

Our study surveyed 255 non-accepting merchants to assess the potential of merchant payments with the Ivorian business fabric. These merchants represent the economic diversity in Abidjan. According to a survey on the informal sector in Abidjan conducted by the National Institute of Statistics of Côte d’Ivoire, there are approximately 610,000 informal production units of non-agricultural market activities in Abidjan. Around 40% of the turnover is from informal trade.

The size of the informal sector in Côte d’Ivoire is considerable and its contribution to the overall Ivorian economy is significant. Hence, the integration and development of merchant payments in this sector could have a multiplier impact on the overall adoption of digital financial services. Our study points out some encouraging attributes of the informal sector.

Merchant payments: An alternative to cash?

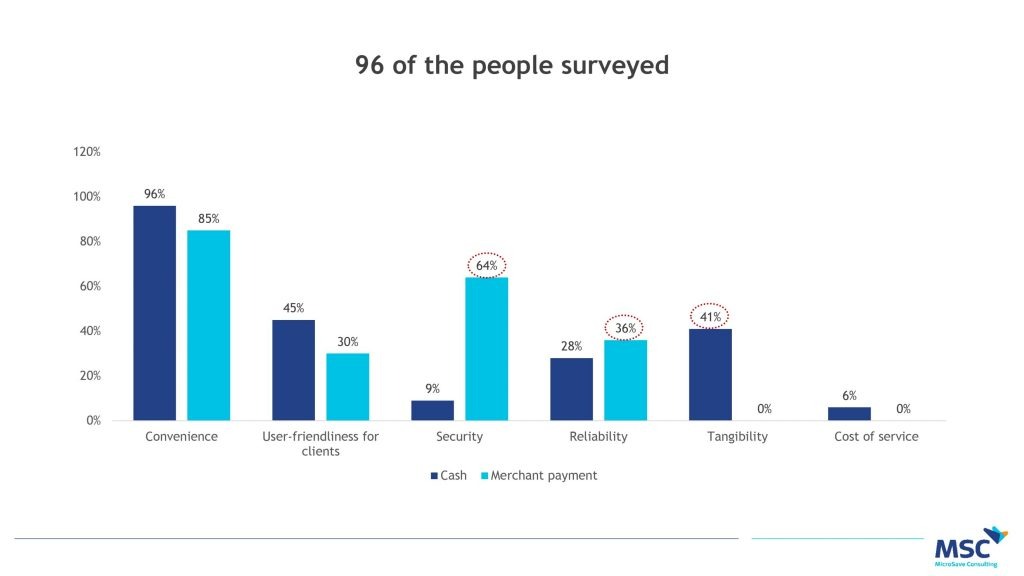

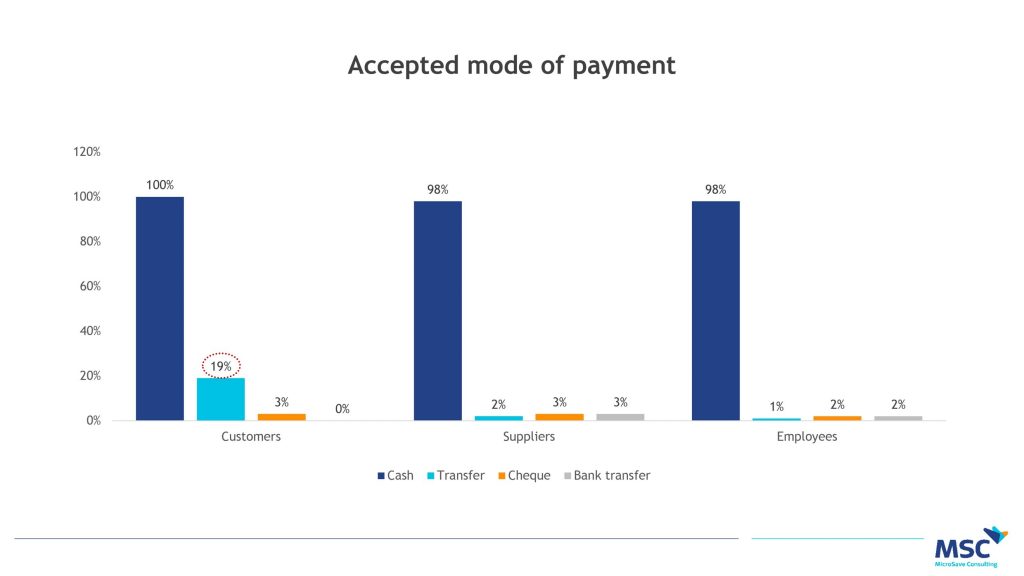

Since its launch in 2016, the businesses that the merchant payments solution mainly targeted are the trade chains and large supermarkets that operate in the formal sector. Indeed, our diagnostic study of the Orange Money and MTN money merchant payments networks indicates that 75% of merchant acceptors of merchant payments are supermarkets, petrol stations, pharmacies, and large bookstores. This strategic choice is understandable given the large geographical scope of these businesses, which are generally part of national trade chains. However, the rate of use of the merchant payments solution in these businesses remains minimal, with only 5% of the total volume of transactions carried out via this payments solution compared to 80% in cash.

Informal sector businesses, which represent 95% of our non-merchant sample, are largely untapped in the expansion of merchant payments. They, however, face many challenges that merchant payments could try to solve. These businesses rely heavily on cash to manage their business (98%) and have limited access to money security and savings and credit options. These merchants are nevertheless aware of the problems generally associated with cash management, such as change, counterfeiting, as well as loss and theft of money, among others.

A majority of businesses identify the lack of loose change as the major problem of cash in the local market. Merchant payments come at the right time since it offers a solution to this problem through digital payments or provision of change. This trend points to the possibility of the proposed merchant payments solution being able to target informal sector businesses that existing suppliers hardly manage to serve.

Moreover, merchants who currently use the merchant payments option find that it has attributes that could meet the needs of businesses in the informal sector. They consider merchant payments to be more secure and reliable than cash or any other means of payment. Businesses deplore the possibility of losing money or having it stolen, in addition to incurring unnecessary expenditure by having cash on hand. Since cash is too liquid and can be easily misused, there is a need for access to money security options and tools that promote financial discipline. Merchant payments, therefore, appears to be an appropriate solution to meet the needs: security and reliability.

Furthermore, most transactions in developing countries are still carried out in cash, as confirmed by the majority of the traders in our study sample.

Does technology have a place in the informal trade sector?

Our study shows that a small proportion of businesses (32%) use technology and the Internet to manage their activities. However, personal ownership of technological devices is high, with 90% of people owning a technological device and one-third owning a smartphone. This confirms GSMA’s report on the mobile economy, which notes that telephone penetration in Côte d’Ivoire is 53%. Secondly, in a local environment where the activity rate of mobile money accounts is below 35%, almost half of the traders surveyed (45%) have an active mobile money account. Therefore, we note that neither the ownership nor the use of a mobile money account—often cited as structural barriers as a previous MSC study suggests—constitute an obstacle to proposing a market solution for the informal sector traders interviewed in our study.

P2P transfers allows customers to send the purchase amount directly to the trader’s personal account. Indeed, traders who accept P2P transfer payments prefer mobile money transfers for large transactions and state security reasons associated with possessing physical cash as the main reason for this preference. Field observations from our study suggest that businesses accept P2P transfers for regular and trusted customers or for paying geographically remote suppliers.

The volumes of transactions and recognized business opportunities in this sector suggest that it is possible to develop a use-case specifically for micro and small informal sector companies that have already adopted the P2P mobile money transfer service for business purposes.

So what can suppliers do to seize opportunities in terms of adopting and using the service as well as making the offer profitable?

Lessons for merchant payments service provider

Suppliers could review their network segmentation strategy and target micro and small businesses. By using person-to-person transfers for commercial purposes, they could design a product for informal businesses. This product could focus on the problems of change, and the need for security and access to financial services.

However, given the specific nature of operations in this sector, we need to factor in aspects, such as convertibility of electronic money, the administrative documents required, and transaction costs.

Go-getters and receptive reticents—Merchants who have the instinct, but need support

This is the second blog in the series on “Digitizing merchant payments in India”. The first blog discusses the potential of the merchant ecosystem in India and the need to design distinct solutions for different merchants. In this blog, we will discuss two merchant personas: a) The go-getters and b) The receptive reticents.

MSC used its Market Insights for Innovations and Design (MI4ID) approach to understanding the barriers to adoption of digital payments by different merchant personas. MSC had also used the MI4ID approach in its cashless experiments in Kerala and Odisha to understand the digital traits and hindrances in the adoption of digital payments products among low-income people. In this blog, we will discuss two merchant personas: a) The go-getters and b) The receptive reticents.

MSC used its Market Insights for Innovations and Design (MI4ID) approach to understanding the barriers to adoption of digital payments by different merchant personas. MSC had also used the MI4ID approach in its cashless experiments in Kerala and Odisha to understand the digital traits and hindrances in the adoption of digital payments products among low-income people. In this blog, we will discuss two merchant personas: a) The go-getters and b) The receptive reticents.

The go-getters

Sanjay is a merchant who operates in the Green Park area of Delhi. He is a middle-aged man and owns a mid-size grocery store that has a high footfall. He is a graduate and clearly shows business acumen. He likes to experiment and is open to trying new payments channels—as long as he sees benefits in them. The heavy traffic of customers in his shop has made him keen to use digital payment services, which offer speed and convenience to customers. Sanjay is also ready to pay for the associated charges. In addition to cash, he accepts digital payments using wallets like MobiKwik and Paytm, as well as card-based payments through a point-of-sale (POS) machine.

Sanjay belongs to the genre of “go-getters” who believe in trying out new payments mechanisms. This segment is not afraid to experiment and shows a remarkable ability and willingness to try out new modes of accepting digital transactions (Behavioral trait: pragmatist). Even after falling prey to a vishing (voice phishing) fraud with one leading wallet provider, where he lost about INR 6,000 (USD 86), he continues using the same wallet because he accepts his mistake and takes the blame. In our interviews, he revealed that the demonetization announcement in November 2016 nudged him to explore the digital channels like Paytm.

What makes Sanjay a go-getter?

This segment of merchants is highly customer-centric and enthusiastic about various modes of digital payments. They play an important role in creating customer awareness and convincing them to pay digitally.

Hence, they have the potential to become “brand ambassadors” of various digital payments channels or products.

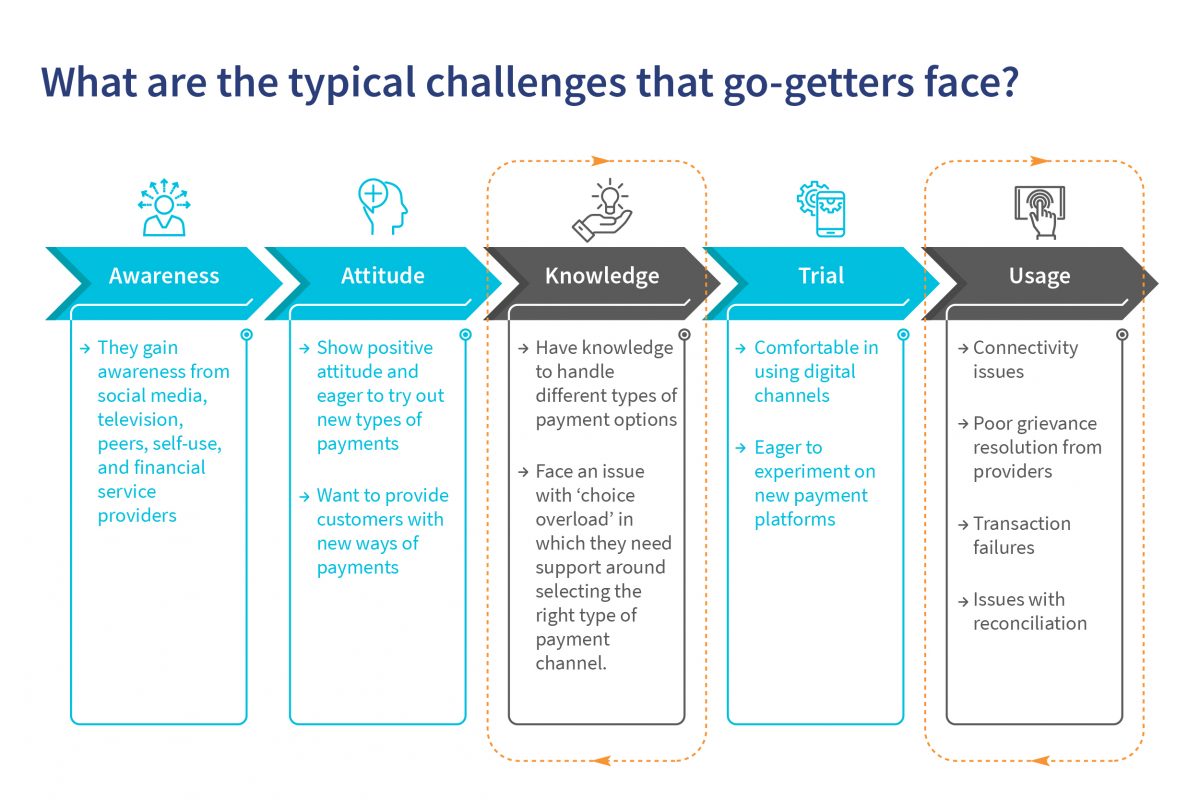

What are the typical challenges that go-getters face?

Connectivity issues mar the customer and merchant experience alike. While our team was interacting with Sanjay, he tried accepting a customer payment on POS. The transaction failed five times before being successful on the sixth attempt!

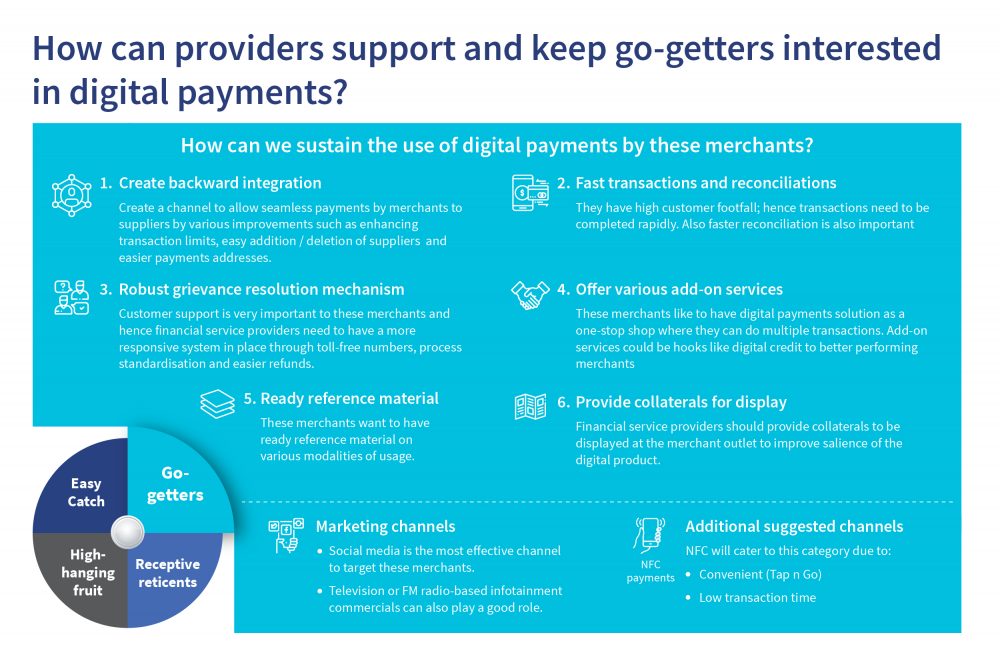

How do we keep go-getters interested in digital payments?

Merchants like Sanjay are the “poster boys” of merchant ecosystems who hold great promise. Supporting them is important for the overall proliferation of digital payments in the country. Hence, acquirers or providers need to create and provide appropriate solutions to them. The diagram below illustrates some ways in which providers can support this category of merchants.

The receptive reticents

Deepak Das, a 40-year-old semi-literate man, runs a grocery store built on his plot at Bhojerhat on the outskirts of Kolkata. He has been managing his shop for 10 years. On average, 30-40 customers visit his outlet each day. He often visits Kolkata with his family for shopping during the festive season. At Big Bazaar in Kolkata, he has seen customers making large-value payments using POS machine or Paytm. However, Deepak himself has never used any digital payments channel for payments. He was not aware that digital channels can be used for small-value payments as well. He feels that using digital channels to make or accept payments is a complex process.

What makes him a receptive reticent?

What makes him a receptive reticent?

The receptive reticent, despite being interested, does not use digital modes of making payments owing to their low levels of literacy or understanding. They are highly dependent on others for handholding and support to comprehend, trust, and use the digital payment modes. They display an accommodative attitude when the customer demands to pay digitally.

The receptive reticents like Deepak accept the payment through a digitally-enabled merchant nearby and later settles it in cash with that merchant. This category of merchants needs to conduct multiple digital payments transactions under a reliable person’s guidance before they can work on their own. In India, urban cultures have been influencing rural areas at an increasing pace. In such a scenario, people like Deepak feels that the day is not too far when people in villages will embrace cashless payments.

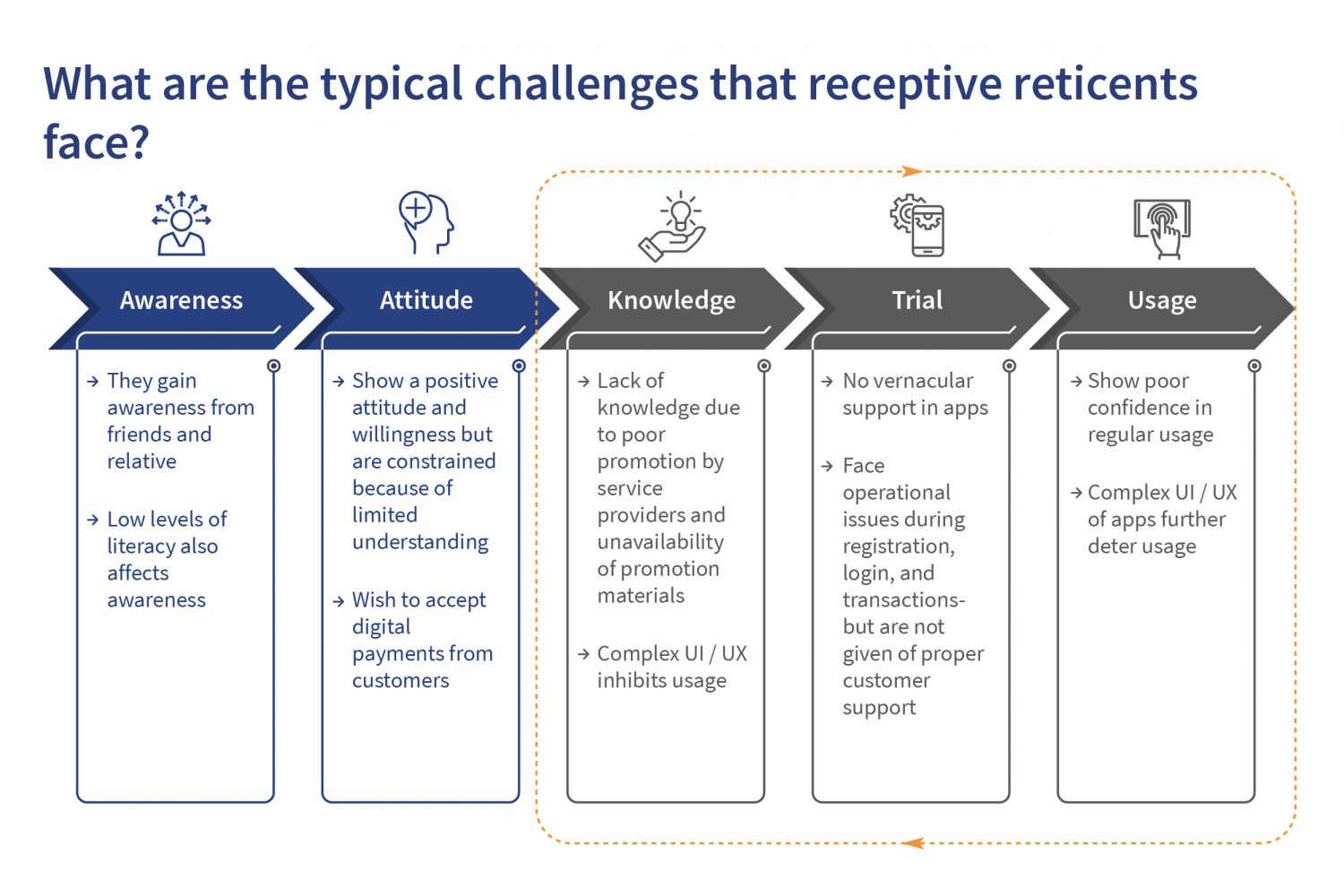

What are the typical challenges that receptive reticent face?

Receptive reticents start taking an interest in digital payments because people around them are interested in them (Behavioural trait: social proofing).However, due to information asymmetry, they do not have complete information on digital payment products and hence, are not able to graduate to the “usage” stage. This merchant category is most comfortable in the local language. The primary source of information for these merchants is word-of-mouth. This makes these merchants susceptible to biased information—which may or may not be correct and depends heavily on others’ experiences. Therefore, they can be dissuaded from adopting digital payments easily. Moreover, such receptive reticents are constrained by the multiple modalities and requirements of using different digital products. These present too much information, which is beyond their limited cognitive abilities. The diagram below illustrates some of the other challenges that this category of merchants faces.

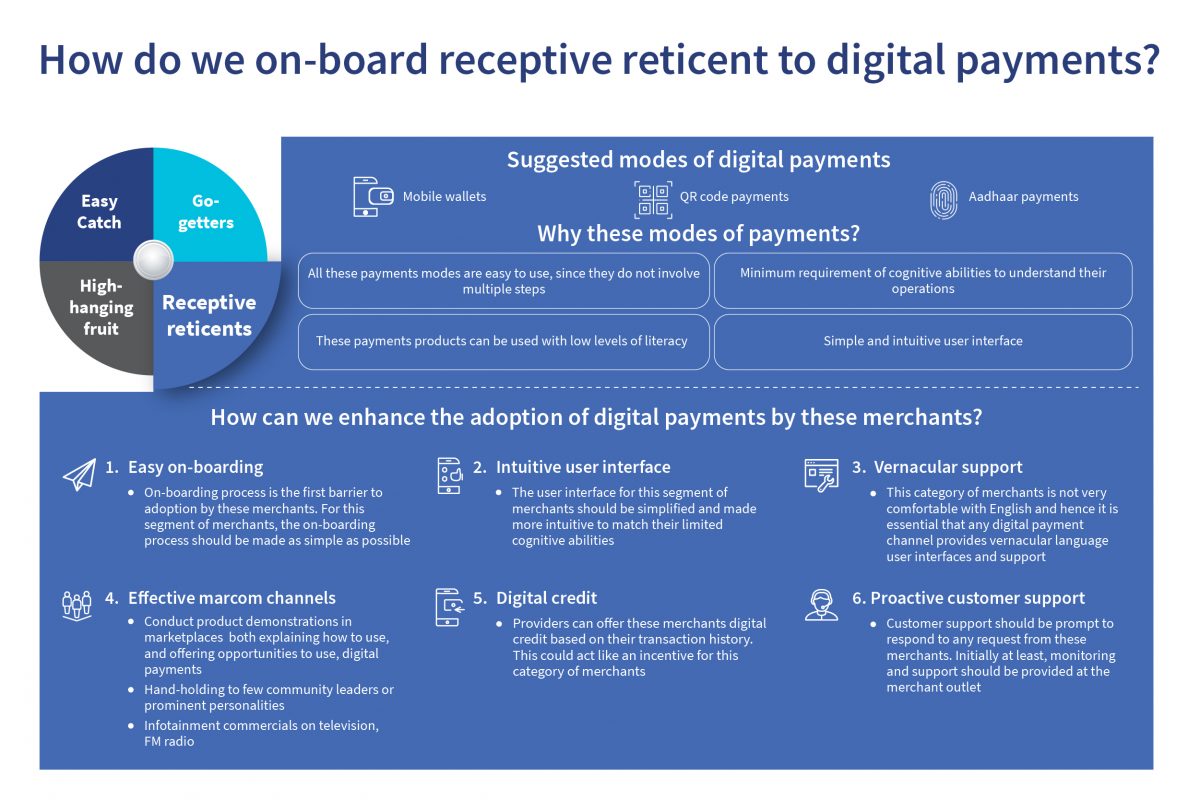

How do we on-board receptive reticent to digital payments?

Receptive reticents need hassle-free digital payments products both for the on-boarding process and to complete transactions successfully. They also need proactive support from providers (probably physical visits to merchant outlets) to train and resolve issues. The UI of the digital payment product should suit their limited cognitive abilities.

“Cookie-cutter” solutions for merchants will not work

Sanjay, Deepak, Pushpa, and Shailendra are merchants in different parts of India who sell goods from their own shops. They interact and transact with a variety of customers on a regular basis. To a varying degree, all four share a few common traits. They feel that digital payments are good for them. All of them have experienced banking and used financial services at different levels. They show a willingness and capacity to become offline merchants and join the digital bandwagon.

Sanjay, Deepak, Pushpa, and Shailendra are merchants in different parts of India who sell goods from their own shops. They interact and transact with a variety of customers on a regular basis. To a varying degree, all four share a few common traits. They feel that digital payments are good for them. All of them have experienced banking and used financial services at different levels. They show a willingness and capacity to become offline merchants and join the digital bandwagon.

What is it that makes them different from each other?

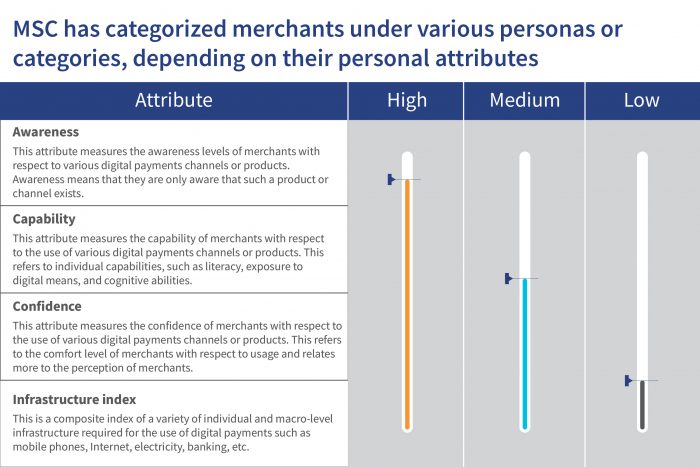

When it comes to accepting digital payments, each of these merchants sells different types of products, have different financial lives, and exhibit different levels of motivation. They meet different types of customers—some who are “pro-digital payments” and others who do not understand or wish to understand the role or benefit of paying digitally. We have used the following four parameters to segment merchants into distinct personas.

Merchants like Sanjay and Deepak are positive about digital payments and continue to pursue their customers to pay digitally, whereas Pushpa and Shailendra seem less enthusiastic. All four of them need different types of nudges and forms of support to accept digital payments. They exhibit different belief systems and goals to make choices while accepting payments.

The retail payment landscape in India

The retail payment space in India is proving to be a battleground for digital service providers (DSPs), both for the incumbents like banks and challengers like FinTechs. A BCG-Google study estimates that the digital payments market is set to grow to USD 500 billion by 2020. This includes person-to-person (P2P), person-to-merchant (P2M), merchant-to-merchant (M2M), and person-to-government (P2G) payments. Meanwhile, a recent Credit Suisse study estimates that the digital payments market will grow to USD 1 trillion by 2023. The report says that currently in India, cash transactions account for approximately 90% in terms of volume and 70% in terms of the value of total transactions. With a high affinity to cash, India offers a huge opportunity for payments players.

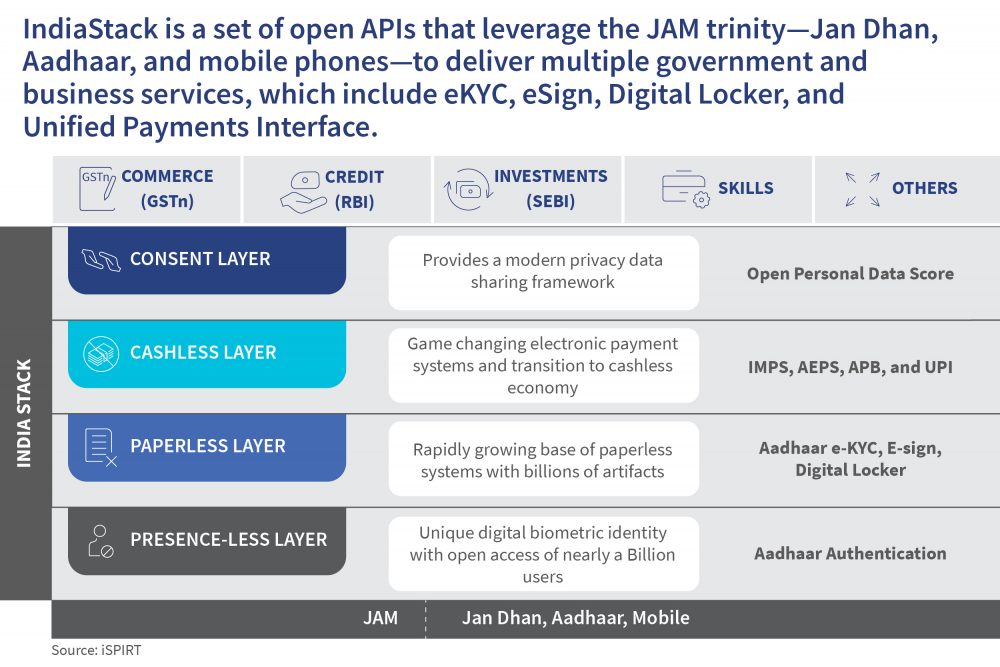

The Government of India launched its flagship “Digital India” program with a vision to transform India into a digitally-empowered society. It prioritized the use of digital payments by each market segment. The vision is to provide seamless digital payments to all citizens of India in a convenient, easy, affordable, quick, and secure manner. To achieve this, the government articulated “faceless, paperless, cashless” as part of Digital India and developed IndiaStack, a presence-less, paper-less, and cashless ecosystem for delivery of services.

IndiaStack is a set of open APIs that leverage the JAM trinity—Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, and mobile phones—to deliver multiple government and business services, which include eKYC, eSign, Digital Locker, and Unified Payments Interface.

The Indian government and the national regulator—the Reserve Bank of India (RBI)—have designed various incentives and policies on the supply side to promote digital payments. One such move was the rationalization of Merchant Discount Rates (MDR) by the RBI to promote debit card acceptance by a wider set of merchants, especially small merchants. As part of this move, the RBI allowed a temporary waiver of MDR for small-value transactions (up to INR 2,000) for two years on all debit card, Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM), Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and Aadhaar-Enabled Payment System (AePS) transactions.

The RBI also permitted cooperative banks, which are well entrenched in rural areas, to deploy their own or third-party point-of-sale (POS) terminals. Cooperative banks can now also install onsite or offsite ATM networks, issue either debit or credit cards or both—either on their own, through sponsor banks or through a co-branding arrangement with other banks.

On the demand side, the past decade has seen tremendous growth in the use of the Internet and mobile phones in India. With a population of 1.34 billion and close to 1.18 billion mobile phone subscribers , 446 million internet users, and 386 million smartphone users, India has all the ingredients in place to develop a vibrant merchant payments ecosystem. The BCG-Google report on digital payments estimates that the size of the person to business (P2B) digital payment market is about to grow to USD 224 billion by 2020. This means that more Sanjays, Deepaks, Pushpas, and Shailendras will join the digital ecosystem—of course, with a little help from service providers.

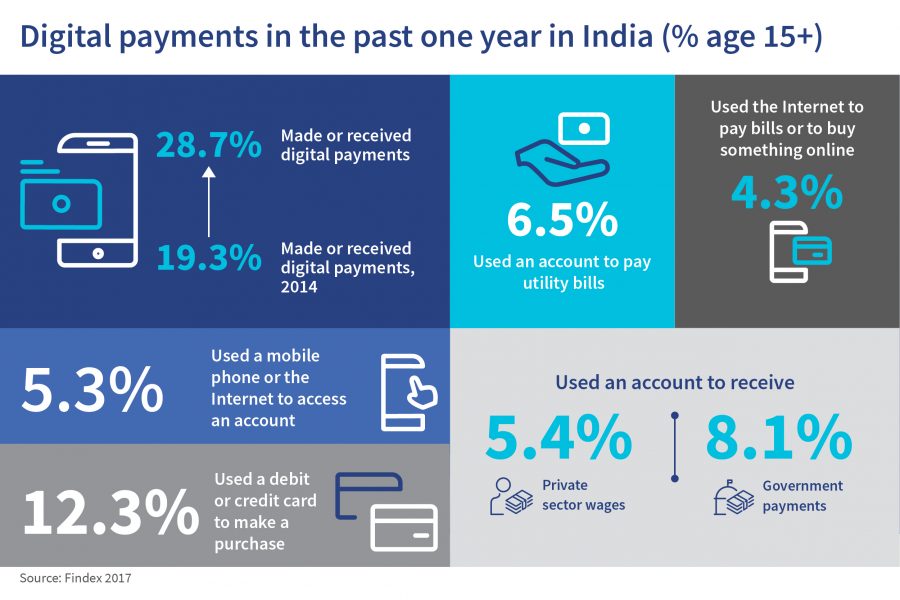

We can also look at the progress in the digital ecosystem in India based on the macroeconomic data from Findex 2017. The Little Data Book on Financial Inclusion 2018 highlights a commendable achievement on access to financial services. The flagship Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) scheme has played a major role, resulting in the creation of bank accounts for close to 80% of the adults, including 76% of women.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for usage. The table shows the percentage of digital transactions conducted by adults in India in the calendar year 2017. This shows how much more must be done to ensure that people transact digitally.

This data shows that there is minimal activity on the side of merchant payments. Only around 6% of merchants in India use digital payments. This means that customers still use cash to make most of their bill payments, while merchants are also happy or content in accepting cash. This, in turn, implies that we need to support more such Sanjays and Deepaks as we motivate more Pushpas and Shailendras.

Considering the size of the economy, India shows an immense potential around merchant payments, which have a high probability to act as a hook for customers to start transacting digitally. MSC’s practical insights highlight that getting merchants to transact digitally is a key challenge. To probe this further, MSC conducted a research activity with merchants—those who accepted digital payments and those who did not—to gather behavioral insights into accepting payments digitally.

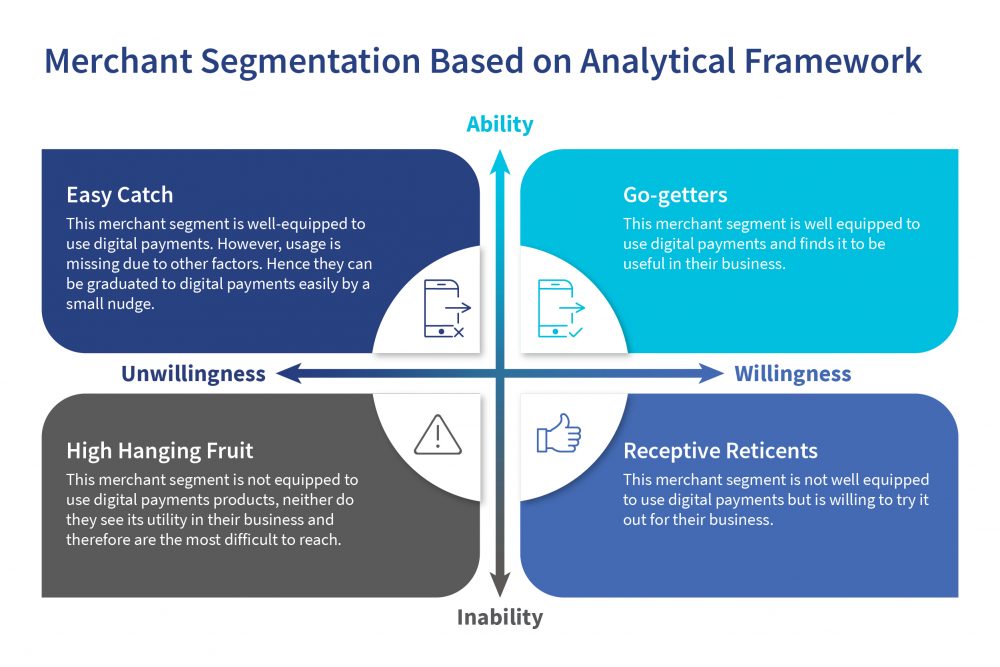

We came up with this series of blogs based on these insights. We have categorized merchants, as shown below, under various personas or categories, depending on their personal attributes, across the two dimensions of ability to accept digital payments and their willingness to do so. These categories are go-getters (Sanjays), receptive reticents (Deepaks), high-hanging fruits (Pushpas) and easy catches (Shailendras). Additionally, there is another category of merchants termed as “drop-outs”. Merchants in this last category have tried digital payments for their businesses at some point in time, but have gone back to cash in the absence of an appropriate value proposition and adequate support.

This series of blogs highlight that providers cannot promote merchant payments through standard “cookie-cutter” solutions. What works for one category of merchants may not work for the other category. We need to look at merchants as distinct personas to decipher their characteristics and explore ways to change their behavior.

DBT in Fertilizer: 4th Round of Concurrent Evaluation – A National Study

DBT in fertilizer is a modified subsidy payment system under the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) scheme. Under DBT, fertilizer companies are paid subsidy only after retailers have sold fertilizer to farmers or buyers through successful Aadhaar authentication via Point of Sale (PoS) machines. Based on a request from NITI Aayog, MSC has been conducting a nationally representative study on DBT in fertilizer.

The objectives of the current round of the study were to identify issues and challenges pertaining to the implementation of DBT at the national level, provide the government with evidence of successes and challenges that could lead to policy-level decision making, and provide actionable solutions to improve implementation.

The current engagement was the fourth round of the study—the first one was in September, 2016 in two districts in Andhra Pradesh, where the pilot project was launched. The second was in January, 2017 in six districts across five states, where the pilot project was expanded. The third round was between July and September, 2017 in 14 pilot districts in across 11 states.