In the previous note “Barriers to Direct Benefit Transfers for Fertiliser Subsidy”, we discussed various barriers to in-kind and cash transfers for fertiliser subsidy. This note discusses potential solutions to improve in-kind transfers and suggests few ideas for cash transfer pilots for fertiliser subsidy.

Blog

Barriers to Direct Benefit Transfers for Fertiliser Subsidy

Fertiliser subsidy is the second-largest that the Government of India provides after food subsidy of which the budget amounted to INR 700 billion (USD 10.78 billion) in the financial year 2018–19. In the Union Budget 2016–17, the Indian government proposed to bring fertiliser subsidy under the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) programme to streamline its distribution. Read our article for more.

Managing loan repayments

The use of credit is an essential part of how low-income households manage to smooth their consumption in the face of “double-whammy” combinations of income and expenditure shocks. The big push for microcredit in the past decade has led to an abundance of microfinance providers and other providers that offer standardized products.

Blankets and wine for financial inclusion – Beyond digital access

Is registration for mobile accounts (wallets) really enough? What is an ideal measure of financial inclusion? The Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) defines a core set of indicators for measuring financial inclusion. The first dimension is access to the services and products that formal financial institutions offer. Yet to achieve meaningful access, we have to solve the significant problems related to float and cash liquidity at the agent level – even in many mature digital financial services markets. Indeed this begs the question – are we serving wine to customers who need blankets?

Services such as KopoKopo add value to merchant services by providing them credit to expand their business. Meanwhile M-Kopa Solar and similar PAYGO providers connect thousands of households to affordable solar power through mobile money. While we acknowledge the accomplishments of such existing services, we are still far from getting the fundamentals right.

In this post, we highlight the need for digital financial service (DFS) providers to invest even more in adapting their products and services for this segment, even in the so-called mature digital economies.

The flood is still here

A story is told about a great flood that was threatening to wipe out an entire island. There were many people on the island who were in danger. Some could swim, a few had small boats, but the majority were helpless. A ship that was passing by arrived to rescue the people. In desperation, a number of islanders started taking to the waters with makeshift equipment – the kind that they use to try to cross the Mediterranean from Africa to Europe. The ship got there on time. A significant number were ‘on-boarded’, albeit in bad shape. At least their lives were saved.

There were, however, a much bigger number of islanders yet to be saved, but people feared that the ship was already too overloaded. A great debate then began between the master of the ship and his handlers. Should they give some blankets and wine that the ship had in stock to the people on board who were cold and starving and then take them to safety? Or should they toss the merchandise overboard to reduce the weight, then save some more islanders in need? The flood in the story represents poverty and the ship represents basic access to products for financial inclusion. The blankets and wine are value-added digital products and the drowning islanders would be the financially excluded.

A middle-ground solution to this dilemma could be to toss the wine and give blankets to those on board while trying to save more people. I am not an expert in nautical matters, but the message is straightforward. If we wish to help people out of poverty through basic access to financial products, it would require us to ensure that this access can provide the products that deliver meaningful value and help low-income customers manage their lives better.

Access: The cost of cash-to-digital-to-cash exchange

Even though digital financial service providers offer digital wallets to many who would not otherwise have formal financial services, the micro-economies they operate in are largely cash-based. This means agents have to incur the cost of rebalancing frequently or deny service to their customers. Some agents have improvised and developed coping mechanisms like private social media groups to ensure that they have the money or float to serve customers. The onus is, however, on DFS providers to invest more in smart cash and float management solutions that help agents ensure that cash or float is always available, regardless of whether they are in urban or remote areas.

The second dimension of financial inclusion according to AFI’s core-set is sufficient ‘usage’ of these services. We may assess this by how often and how conveniently low-income users are able to receive, send, and spend their money. This requires solving the cash conundrum to create an environment where even low-income customers can easily spend their money digitally.

Usage: Illusive digital ecosystems and merchant acceptance

The digital ecosystem is not yet ubiquitous enough in many countries, including East African markets. This prevents users from using digital funds to pay for very much. As a result, digital funds must be converted, often at significant expense, into cash to be used. This, in turn, discourages poor people – and particularly micro-entrepreneurs – from accepting digital value.

Ultimately, we need a largely digital ecosystem that allows even a street vendor to spend most of their money at other small and micro-businesses. Merchant services are typically designed for medium-sized enterprises that may already benefit from more advanced banking services at the back-end. Point-of-sale devices for merchant services such as Quickteller in Nigeria and 1-tap in Kenya typically exist either at a steep price-point or make overbearing demandson micro-businesses. Safaricom’s One-tap partially addressed this by pricing their device at a relatively affordable KES 2,000 (USD 20). However, this is an exception and there are few other examples in developing markets.

Some providers such as Equitel1 in Kenya and Paytm in India have offered free peer-to-peer transfers for customers. Customers indeed use them to send and accept micro-value payments. We recognise that such users who accept payments in this way may not meet relatively stringent requirements, such as tax compliance for small and micro-merchants. Considering that a significant proportion of micro-businesses in developing markets operate informally, merchant services designed for them must be both simple and affordable. These small merchants require a tailored and targeted design of products. Targeted design of services may require more creative incentives but could graduate these merchants to become long-term business partners for providers.

Policy can also encourage digital payments by waiving charges for low-value transactions. Towards the end of 2017, the Government of India waived the merchant discount rate2 (MDR) for transaction values below INR 2,000 (approximately USD 30). The Government of India has been paying the banks on behalf of merchants and customers to encourage usage and acceptance of digital payment methods.

Quality: Products not tools

The quality of digital financial products is AFI’s third dimension of financial inclusion and is, at best, still nascent for low-income consumers. Remember those who could swim and had small boats from the story of our drowning island? These are those who we colloquially refer to as ‘cuspers’ – a demographic that is just shy of the proverbial middle-income or thereabouts. We recognise that laudable efforts have unlocked more financial services for the cuspers and the middle income, who comprise the wine from our analogy. But wine is not the best sustenance for our islanders – in the same way that the digital products on offer are not the most appropriate.

The swarm of digital savings and credit products that have invaded developing markets offering easily accessible loans is a good example of this. Unfortunately, the results bear striking resemblance to microfinance in its early years. As highlighted in MicroSave’s recent research in Kenya, the burgeoning digital credit products do not yet offer low-income borrowers real value. In contrast to the celebration of digital transactions and consumer loans, there is very little discussion around or evidence of digital micro-savings. Typically, users do not save for a future expense or aspirational investment. Instead, they only save to try to game digital credit systems to qualify for higher value loans.

There is a real need for appropriately designed tools to help the low-income segment manage their limited resources more effectively. As we can see from the growing array of fintech offerings, the digital revolution enables us to do this. But it will require real focus as fintech is irrelevant for most people in the low-income segment, as providers have made little effort to tailor interfaces or use-cases for this market.

The vast majority of fintech providers develop solutions for the affluent and middle classes. This makes logical sense – these segments have the money and connectivity to use the solutions. Furthermore, fintech developers typically come from this background. They, therefore, understand the challenges this segment faces and thus the opportunities it provides. In contrast, when and if fintech developers focus on the low-income segments, they tend to create solutions and then look for problems to solve in preference to understanding the needs, aspirations, perceptions, and behaviour of the poor first.

Ultimately all that matters is impact – do not let them drown!

The fourth dimension of financial inclusion according to AFI is impact. Digital financial services have definitely had an impact on the lives of both users and non-users of such services, including through direct and indirect employment. However, we are yet to solve a number of fundamental design issues with these products. A few exemplary outfits such as Twiga Foods have taken an ecosystem-based approach to understand the low-income segment and solve their financial and social inclusion issues. Real value, as Twiga has shown, can go beyond accessing formal financial accounts to solve day-to-day problems like accessing markets to buy and sell products.

Such success needs to cascade further down the consumer income brackets. Improving access to financial products, usage of the services, and quality of those products and services for the lower-income segment requires significant investments from financial service providers, and especially fintechs, if they wish to look beyond offering traditional one-size-fits-all products.

1Equitel has recently withdrawn their free peer-to-peer mobile money transfers, although their website maintains that on-net (equitel-to-equitel) transfers are still free.

2MDR is the fee that the store accepting your card has to pay to the bank when you swipe it for payments. The MDR compensates the bank issuing the card, the bank which puts up the swiping machine (Point-of-Sale or PoS terminal) and network providers such as Mastercard or Visa for their services

Why do so Few Fintechs Focus on the Mass Market?

Howls of disbelief and denial greeted the assertion in Can Fintech Really Deliver On Its Promise For Financial Inclusion? that “fintech is irrelevant for most villagers because providers have made little effort to tailor interfaces or use-cases for the low-income market.”

At the time of writing, the vast majority of fintech providers across the globe continue to develop solutions for the affluent and upper-middle classes. This makes logical sense – these segments have the money (and connectivity) to use the solutions. Moreover, fintech developers typically come from this background. They, therefore, understand the challenges this segment faces and thus the opportunities it provides. In contrast, when and if fintechs focus on the low-income segments, they tend to create solutions first and then look for problems to solve in preference to understanding the needs, aspirations, perceptions, and behaviour of the poor first.

But this is an inconvenient truth that is not without substance. In 2017, MicroSave conducted research with fintechs and FSPs across six markets for the MetLife Foundation – Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, and Vietnam. The research identified the key challenges in financial inclusion for each market and assessed the readiness of the market for the supply and adoption of fintech.

This research reaffirmed what we had already seen in Africa – the enthusiastic app developers had a “limited understanding of the demand-side behaviour of rural customers”, a “lack of resources to prioritise business development and build new modalities – specific niche segments (for instance, SMEs)”, and were constrained by the “cost of serving low- and middle-income customers”. Furthermore, many were hampered by the disappointing realisation that, in the words of one entrepreneur, “most innovation labs are jumped-up office-sharing spaces” that offer little or no support services, and still less mentoring.

We had hoped that in India, as we studied the fintech landscape for the JP Morgan Chase Foundation and CIIE, we would find a different reality. But we found the same story here.

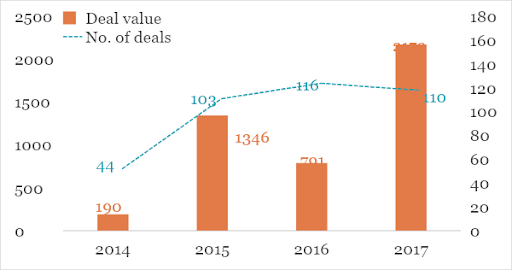

There are over 1,500 fintechs in the country at the time of the study – a number that has been rapidly growing. India has more than 350 active angel investors and more than 170 active venture capitalists across the country. Unsurprisingly, the fintech market in India is growing rapidly in terms of numbers, transactions, and reach.

Investment in the fintech sector has also seen significant growth over the past few years, as seen from the adjoining graph.

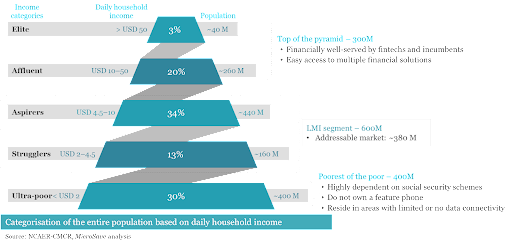

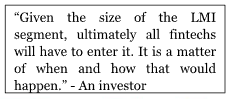

Most fintechs, however, serve affluent, tech-literate customers in the larger cities, leaving over 80% of the addressable low- and middle-income (LMI) market untapped. Fintechs in India typically focus on one of two market segments:

1. Millennials who seek financial independence:

• Active users of smartphones;

• Consume mobile Internet for multiple purposes;

• Value technology and prefer convenience;

• Largely from the salaried class.

2. Small and micro-entrepreneurs:

• Accept digital payments;

• Require affordable credit;

• Use smartphone for communication and entertainment;

• Explore the value proposition of fintechs.

Yet, as can be seen from the population pyramid below, this represents a minuscule part of the overall population.

So why do fintechs avoid the LMI market?

There are five barriers that fintechs face while serving the LMI segments.

- Lack of knowledge and understanding of the segment: It was clear from our analysis that fintechs come up against barriers because of a limited understanding of the LMI market and its potential to deliver profits. A staggering 82% are located in three main cities –Mumbai, Bangalore, and Delhi – and had little knowledge and understanding of or empathy for the LMI market.

- The LMI is a challenging market segment: Addressing the LMI segment is indeed challenging. LMI customers are expensive, not just to acquire, but also to serve. As we have seen in multiple studies, LMI customers struggle to understand or trust digital financial services – particularly when they are either unreliable or the systems for resolving grievances are poor or both. The segment prefers cash – not least of all because it is more intuitive, particularly for those who are “oral”, that is, illiterate or innumerate.Finally, many of them, particularly women, do not have access to a feature phone, let alone a smartphone, on which to transact. Estimates from eMarketer indicate that only 20.8% of India’s population used a smartphone in 2017. The penetration rate of mobile phones of any type – feature or smartphone – was only 57%.Finally, most entrepreneurs feel uncertain about the long-term value – which investors define as up to two years – that LMI customers offer. The entrepreneurs were concerned by the limited digital footprints of LMI customers to inform fintech algorithms. Besides, there are still plenty of opportunities for fintech in India’s larger cities. It has not only been easier to raise funds to serve these segments, it is also easier to get the media coverage to promote the service.

- Lack of investor interest in the LMI segment: Investors, too, are wary of the LMI segment. They have a limited understanding of the segment and have a clear preference for established models.

This is amplified by the fear of missing out.So when the approach of a fintech to a specific problem – say credit for SMEs – is deemed to be working, then investors are keen to rush in as quickly as possible. Until models are demonstrated, they are unsure of the LMI segment, its potential, and market-readiness.Perhaps most of all, there is a mismatch between the size and timing of returns on investment. Investors look at unit economics and want quicker returns than serving the LMI segment is likely to deliver. Nonetheless, as fintechs that serve the LMI segment prove their worth, investors will increase their limited investments in fintechs serving this segment.

This is amplified by the fear of missing out.So when the approach of a fintech to a specific problem – say credit for SMEs – is deemed to be working, then investors are keen to rush in as quickly as possible. Until models are demonstrated, they are unsure of the LMI segment, its potential, and market-readiness.Perhaps most of all, there is a mismatch between the size and timing of returns on investment. Investors look at unit economics and want quicker returns than serving the LMI segment is likely to deliver. Nonetheless, as fintechs that serve the LMI segment prove their worth, investors will increase their limited investments in fintechs serving this segment.

- Lack of access to investors: Unsurprisingly perhaps, given educational and social norms in India, very few fintech entrepreneurs are from the LMI segment. Furthermore, those that do come from the LMI segment typically have a remarkably poor awareness of investment options to finance their ideas and prototypes. This is in part because of limited knowledge of how to pitch to investors and in part because they lack access to potential investors.

- Lack of adequate or appropriate mentoring: Not only do fintechs lack familiarity with the LMI segment, they also have a limited or no access to mentors and inadequate support from the incubators and accelerators in which they work or simply share office space with. This may be because only 15 of the 140+ incubators in India specialise in fintech.Most Indian incubators are sector-agnostic, and the 15 that focus on fintech are typically run by incumbent financial service providers that have their own agendas. Sector-agnostic incubators struggle to provide expert – and thus valuable – advice, mentorship, or links to financial service providers. Instead, entrepreneurs are offered standardised, generic packages of inputs on how to run build and run a business, how to pilot and pivot, etc.

Despite these misgivings, fintechs have the opportunity to cater to the LMI segments. Our research characterised the LMI segments into five distinct personas – each of which is at a different level of readiness and adoption of digital services (see the exhibit below).

Despite these misgivings, fintechs have the opportunity to cater to the LMI segments. Our research characterised the LMI segments into five distinct personas – each of which is at a different level of readiness and adoption of digital services (see the exhibit below).

A completely different type of approach is needed for fintechs to cater to the LMI segments effectively. We envisage this in the form of an innovation lab that can address the five barriers outlined above. The lab will not only specialise in and be firmly focused on fintech for the LMI segment, it will also offer:

1. Assistance and opportunities for entrepreneurs to deep dive into the market to understand their needs, aspirations, perceptions and behaviours – and thus the problems for which solutions can be developed;

2. Support to understand and comply with the complex legal and regulatory environment that governs the provision of financial services;

3. Significantly higher levels of expert and dedicated mentoring;

4. Links to, and alliances with, financial service providers serving the LMI market; and

5. Introductions to angel investors and venture capitalists interested in the LMI market.

Click here to read about the innovation lab in greater detail.

Winter is coming: Digital disruption and its impact on the financial services industry

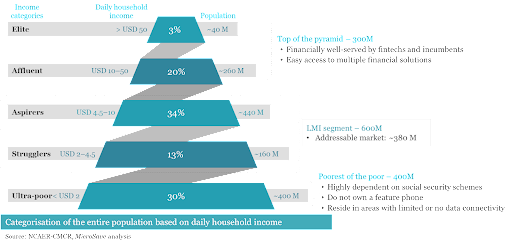

The financial services industry is changing rapidly. A convergence of technology with finance, which, in turn, resulted in the emergence of FinTechs, has been changing the very fundamental nature of the financial industry. Apart from technology, demographic and cultural shifts continue to alter the financial services value chains. Traditional financial institutions are losing their market share to technology-enabled entrants due to specific factors. The table below showcases these in detail.

Banking and financial services used to be the stronghold of traditional financial institutions or the “incumbents”. These providers had a number of advantages related to their size and scale and were able to serve a substantial part of the market. However, many have also had high-cost branch networks and legacy IT systems. This rendered them sluggish to adapt to the new digital world and also led to some consumers being considered unprofitable, with negative consequences for mass market growth.

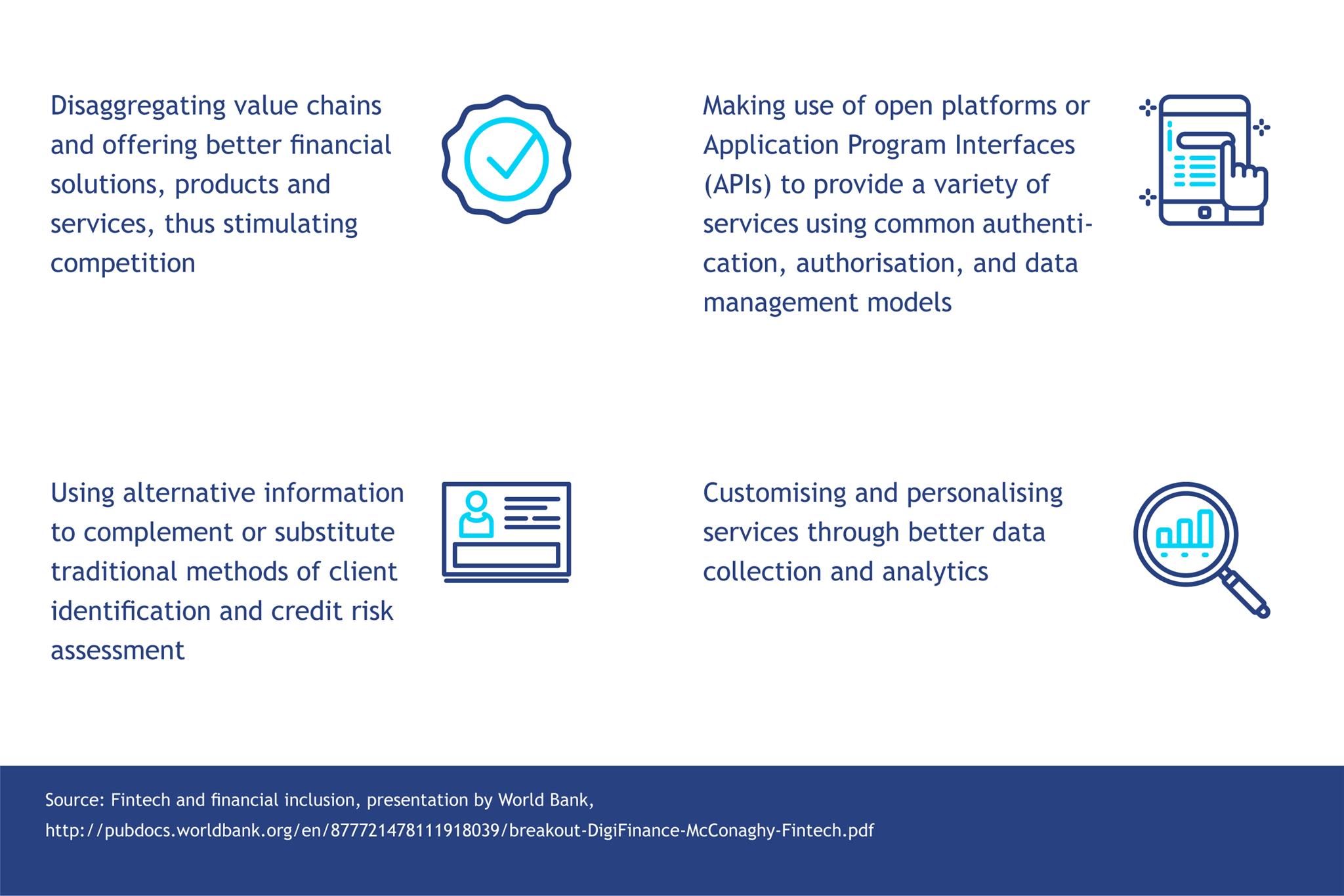

In the past, the financial services industry used to have high barriers to entry with respect to capital and regulatory requirements. However, these entry barriers have been gradually reducing, thereby spawning innovative, technology-enabled entrants who disaggregate the financial services value chains and challenge the incumbents.

The landscape and context are changing. Market share, revenue, and profit have ultimately defined institutions in the financial service industry.As the prominence of these financial institutions dwindles, technology-enabled entrants have emerged to fill up the void. Since FSPs had not been able to meet the evolving needs of customers, the emergence of technology-enabled entrants has largely been a demand-side phenomenon. Such entrants target strategic niches, develop customer-centric solutions aimed at achieving a specific objective, improve customer experience, and interface and deliver these solutions using technology. They disrupt the financial services and financial information in a number of ways. The table below illustrates these.

The question is, “How is the rapid digital disruption of the financial services industry affect the incumbents?” Financial institutions struggle to balance three potentially-competing objectives:

- To provide financial intermediation services at a cost that makes business sense for the financial institution;

- To reach a large number of customers efficiently; and

- To accomplish the first and second objectives while managing the risks.

Financial institutions often find that these three desired objectives are not independent of each other and may require trade-offs. However, with the use of the digital disruption tools, agile and nimble entrants have found a way to manage the right balance between these objectives by:

- Using technology-enabled channels, such as mobile phone and agents to provide financial intermediation services at a significantly lower cost compared to the incumbents;

- Making use of digital means to reach a large number of customers at one-tenth of the cost compared to the incumbents;

- Identifying, monitoring and managing a variety of risks associated with financial service provision using technological approaches (artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML) and auto triggers).

With the use of technology, the entrants have managed to:

- Improve customer experience by making it easier and more intuitive to perform financial transactions and by providing more transparency in the process;

- Provide better access to financial solutions using advancements in technology to allow customers and businesses to transact anytime, almost anywhere in the world. and across a range of devices;

- Lower operating costs and increase process efficiency using the new tools developed through technological innovations – the tools transform the way financial services firms operate by making the processes faster and more efficient.

The entrants have a significant edge over the incumbents in the following areas:

The end-users of financial services prefer the entrants over the incumbents. This is because of ease of use, faster services, good experience, lower cost of access to financial solutions, availability of a higher number of services and features, value-added services, instant gratification, and highly personalised services.

The end-users of financial services prefer the entrants over the incumbents. This is because of ease of use, faster services, good experience, lower cost of access to financial solutions, availability of a higher number of services and features, value-added services, instant gratification, and highly personalised services.

It is worth noting that the incumbents have an edge over the entrants when it comes to existing customer bases, innate customer awareness, human touch, and regulatory clearances or compliance. If they are able to utilise these and transform digitally, they have high chances to retain or even enhance their market share.

Digital disruption has the potential to shrink the role and relevance of the incumbents. But it simultaneously helps them create better, faster, and cheaper services that can render them well-equipped to better serve their customers. In order to avail of these opportunities, traditional FSPs need to acknowledge the digital disruption, overcome institutional complacency, and embrace digital transformation.

In the next series of this blog, we discuss how traditional financial institutions can go about the digital transformation to utilise the disruptive power of technology, innovation, and digital disruption.