We presented in our earlier blogs how over the counter (OTC) was growing in leaps and bounds due to various reasons but the key stakeholders were still not satisfied. The question we have been asked in various interactions is – is there a way out?

The clichéd statement appears true in this case – Getting in is easy, getting out very difficult! Whether it’s EasyPaisa in Pakistan or Tigo in Paraguay, the operators appear to be trying.

A key characteristic of OTC is that clients generally have no incentive to put their money in the mobile wallet. They just go to the agent, hand over the cash and the transaction gets done. This has a few fallouts, one the customer doesn’t keep any money in the wallet, all the transfers received are immediately withdrawn in full. As a result, no transactions can take place on an empty wallet.

If we trace the roots of such deployments, we see that the customers have actually witnessed several changes in the way they do financial transactions, one- it’s faster, two –it’s cheaper, three – it’s done at an agent nearby! So while the landscape has significantly changed, there has been negligible change in the behavior of the customer.

The quintessential question is – what will drive the customers to initiate the transactions themselves? In other words, change his behavior. In our view, there are several ways through which this could be attempted.

- It is definitely important to know who these customers and their beneficiaries are why they have been doing assisted transactions till now and what are their needs (both stated and unstated). This could be easily provided the agent device captures this information. If it does not then put this in place this could be the first step towards moving from OTC to self-initiated transactions. This should then be supplemented with qualitative research to gain a deep understanding of and insights into why customers and beneficiaries are using OTC, as well as what might cause them to open and use a wallet.

- One of the key change triggers is consumer marketing and education. The customer will need to know that it is possible for him to make transactions for himself and that it is not rocket science. The right kind of graphics and messaging is important to induce a trial. The protagonist has to be someone the customer can identify with – an uneducated person, or a middle-aged person seeing the agent doing the transaction and then attempting himself and saying, “It’s so easy, even I can do it!”. In addition to this, there has to be a clear message on why is it better than OTC – which of course will be built on the basis of the insights from the qualitative market research. This has economic fallout – the agents may be up in arms since we will be taking their customers away, but they will need to be explained that the cash-in commission would still be theirs. And to sweeten the pill, the cash-in agent could, initially, get a little bit more if the customer does a transaction himself after cash-in. That way he will help change in behavior as he thinks that his commissions are protected.

- It’s also important to get funds into the wallet easily. If the customers were to get their salaries or benefit payments directly into the wallet, then there all chances that the customer would not visit the agent to withdraw cash and then hand it back to him to remit to some! This would naturally aid the change in behavior for the customer.

- Technology led processes could be triggered to identify and deal with such transactions. Safaricom, for example, built logic in their platform to study patterns as customers actually asked the agents to deposit directly in someone else’s account. They focused on looking at the originating and terminating mobile numbers/locations. This allowed them to identify which transactions were being made OTC. On the basis of this information they were able to identify the location of the cash-in agent and the cash-out agent; and if there was no intervening P2P transaction before a cash-out is done, that would be classified as a direct deposit and the cash-in agent would be surcharged for that transaction. The operator would also use BTS’s (Base Transceiver Station) to validate their conclusions. An agent conducting a cash-in transaction in point A that leads to a cash-out transaction in B within a very short time, for example, would be considered to have made a direct deposit, and his commissions would be clawed back and warning letter issued.

- The cash-in process could be tinkered with to make cash-in a bit more engaging for the customer. Warid Telecom created a two-step process for cash-in, making it a bit more involved for the customer and more secure. The transaction had two components. The cash-in was initiated by the agent, but the customer needed to complete it. This ensured that the customer could not deposit the cash in someone else’s account. Also, it solved for problems arising due to making deposits in the wrong accounts. Making cash-in complicated could also be done by the agent asking for and verifying the ID and the mobile number of the person depositing cash.

- A more potent tool could be incentivizing self-initiated transactions. The customer could get benefits by way of getting some extra talk-time, some music downloads, some free internet-time. These offers could be for telecom products and will be easier to bundle since the telecoms usually “produce” them hence the perceived costs could be much higher than actual costs. These could be accompanied by lucky draws, lotteries, etc. where a much bigger prize, say a Motorbike, or television could be given away to a select few. The output will be much greater than the associated costs.

- Introducing some exclusive payment products that are just not available with the agent version of that application could be another tool. For example, bill payments, for which the payer needs a receipt to confirm that they have paid, could be made self-initiated as the biller would issue an electronic receipt only to the payer. Making such payments OTC leaves no trail or scope for a personalized receipt. Or if the mobile money product offers the “best telecom deals” on self-usage. If the customer got “full talk time” on even small value recharges, then the customer is most likely to try and cash-in the benefits. This will trigger self-usage and overtime get him to try other products as well. This could initially result in the “Can you do this for me?” syndrome but over time this is likely to become self-initiated.

- Another way of looking at this could be charging a differential pricing for services, by making transactions much cheaper if they are self-initiated rather than assisted by an agent. This may lead to the agent getting several customer accounts opened in the name of his family members but “adding a beneficiary” functionality (where the customer can only send to a pre-added beneficiary) could make it work. This will dis-incentivize the agent but incentivize the customer.

- An alternate way of exploring this could be to ensure that the cash stays in the wallet for a longer time. For that, it may be a good idea to charge much higher for cash-out. So the customer could actually put the cash in the wallet and then start transferring the cash for remittances or payments. Cash-out pricing could be a deterrent and cash stays on the network. But for this to work there should be large enough network of merchants where the customer could ideally spend without hesitation – in most countries, this is some way into the future.

- The agent could also be bound by velocity rules, which allow him to do only a certain number/value of transactions per day, a post which his wallet will not be able to initiate any transactions. Along with this, the operator will need to keep a tab on the number of agents in a specific location. It’s possible that the agent will seek other SIM/accounts to keep doing these transactions. But at some stage, they will have to decline a few customers. This method could leave the customers in angst since they will be denied service and may not augur well for the brand.

- If nothing else works, there may be a need for change in regulation that will restrict the agents from doing certain types of transactions! For example, remittances could only be self-initiated while the agent could do train bookings or other payments for the customer.

Clearly, there are several alternatives which could be tried. The above list is in no way exhaustive, there could be several other innovations that could be tried. But the fact remains that there is a need to start trying these to reduce the popularity of OTC.

As for the question we asked in the beginning, there definitely appears to be a way out, but it will need a will of steel and management commitment to implement it. Change in behavior is not easy and needs to be pursued continuously before any significant results are visible.

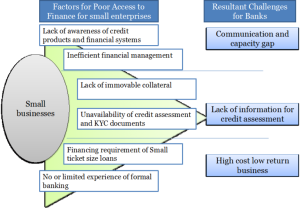

The reasons for such dismal access to finance by small businesses are ingrained in the very business and financial nature of the enterprises. On the demand side, small businesses have limited managerial capabilities and financial management skills, lack appropriate documents and require small ticket size loans. On the supply side, banks lack credit information about the client segment, perceive small businesses to be risky, and see financing to small enterprises as a low revenue activity with high costs of customer acquisition and servicing.

The reasons for such dismal access to finance by small businesses are ingrained in the very business and financial nature of the enterprises. On the demand side, small businesses have limited managerial capabilities and financial management skills, lack appropriate documents and require small ticket size loans. On the supply side, banks lack credit information about the client segment, perceive small businesses to be risky, and see financing to small enterprises as a low revenue activity with high costs of customer acquisition and servicing.

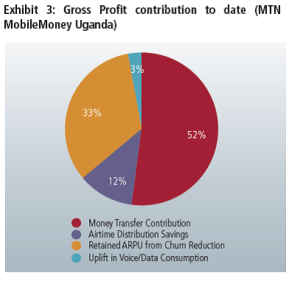

“For MTN Uganda, these numbers are exciting. We found that indirect benefits unique to MNOs – including savings from airtime distribution, reduction in churn, and increased share of wallet for voice and SMS – combined to account for 48% of MobileMoney’s gross profit to date” – Paul Leishman in MMU’s “

“For MTN Uganda, these numbers are exciting. We found that indirect benefits unique to MNOs – including savings from airtime distribution, reduction in churn, and increased share of wallet for voice and SMS – combined to account for 48% of MobileMoney’s gross profit to date” – Paul Leishman in MMU’s “

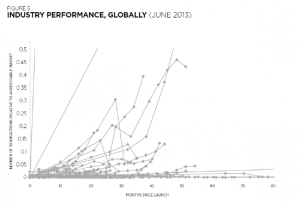

Let’s first look at the needs of the MNOs. Mobile money business has three drivers: (1) scale; (2) throughput and (3) yield. Very few MNOs (out of 219 deployed so far) have witnessed a hockey stick growth with mobile money deployments

Let’s first look at the needs of the MNOs. Mobile money business has three drivers: (1) scale; (2) throughput and (3) yield. Very few MNOs (out of 219 deployed so far) have witnessed a hockey stick growth with mobile money deployments