With 50% of cash-in/cash-out agents conducting at least 30 transactions per day, it is evident that Uganda is one of the world’s leading digital finance markets. However, despite its impressive growth, many operational challenges still persist. The Helix Institute of Digital Finance’s ‘Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Uganda Country Report 2013’ (conducted by MicroSave and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation) analyses both the operational factors of success, and residual challenges in agent network management in the country. Here I highlight four key findings from the report and discuss their implications for market maturity and the direction of its future development.

72% of agents are located within 15 minutes of a rebalancing point.

Unfortunately, this is not a positive indicator, but a result of agents having trouble surviving outside of areas where rebalancing is quick and cheap – along the road network and near financial institutions (see similar findings here in Tanzania). To extend the reach of the networks farther, time must be spent on resolving major operational issues such as liquidity management, monitoring and support.

This problem of ‘liquidity tethering’, (see Emerging Trends for Agent Networks in 2014), is prevalent across the industry. Looking at Uganda, where 43% of the entire population, and only 34% of the poor population, live within 5km radius to a financial access point, increasing the geographical reach of agent rebalancing services will be key to creating a ubiquitous and genuinely inclusive digital financial sector in the country.

Profits are high with 40% of agents making at least US$100 of profits a month.

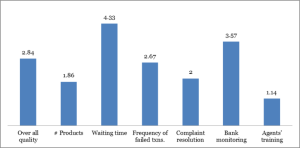

Although agents are generally happy with their financial gains, data shows they could be earning significantly higher profits. With a median of ten transactions per day being denied due to service downtime, b Ugandan agents could increase their daily transactions by 33%, if this issue was addressed. Although similar challenges plague the industry internationally, researchers were surprised by how much it was affecting the ability to serve customers in Uganda.

This issue, however, can also be seen as a symptom of the industry’s rapid growth and success, as transaction volumes regularly overwhelm platforms that were not designed for such scale.

This issue, however, can also be seen as a symptom of the industry’s rapid growth and success, as transaction volumes regularly overwhelm platforms that were not designed for such scale.

Changing or updating platforms is a costly and lengthy process with which providers are currently struggling. In the meantime, providers need to focus on minimising the impact at the agent level by giving them timely and accurate warning about system downtime.

Agencies are “new”, with more than half having been in business for less than one year.

Once again this figure may come as a surprise due to the maturity of the Ugandan market. Data shows this high percentage of nascent agents is a result of both rapid growth and agent churn (agency’s closing and tills being given to other agents). However, be it growth or churn, the large number of inexperienced agents in the market undoubtedly impacts the quality of service delivery. (Further research will need to be done to distinguish the level of contribution of each factor.)

Given agents are the face of the brand, and can play an important role in building trust in the system, the issue becomes – how do you cost effectively train them, and then monitor and support them in the field given many have a short life-cycle? Here, incisive agent selection is key, as is strategically spending monitoring and support budgets as the agents mature.

Banking services (credit, savings and insurance) are almost non-existent.

According to Pew Research, in Uganda 50% of cell phone owners regularly make or receive payments on their phone. Further, InterMedia reports half of households registered with mobile money store money on their m-accounts, meaning the country is already at a level of maturity where people feel comfortable leaving a little float on the system.

However, innovation of new products in Uganda remains almost completely absent, leaving agents primarily doing cash-in and cash-out. Bill pay and airtime top-ups are available, but mostly over the handsets, and integration with banking services is recent, and not being offered on the agent level at scale.

However, innovation of new products in Uganda remains almost completely absent, leaving agents primarily doing cash-in and cash-out. Bill pay and airtime top-ups are available, but mostly over the handsets, and integration with banking services is recent, and not being offered on the agent level at scale.

Opportunities for product innovation, which would increase the amount of transactions each registered customer does on the system, are abound and agents can play an important role in selling them to the mass market, if providers strategically include them.

Click here to read the ‘Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Uganda Country Report 2013’ in full, and delve deeper into the data on Uganda’s operational factors for success and opportunities for improvements as the market moves into its next stage of maturity.