MSC conducted a research study to assess what the low- and middle-income (LMI) segments in Uganda understand about COVID-19 in terms of awareness, preventive measures being taken, gender dynamics at play in their households, and the use of digital financial services during this time. We present our findings in this report. We note that overall, the response from the government has been proactive and generally effective. The LMI segment is largely aware of the disease and knows what precautions to take to prevent further spread. However, more can be done. Hence, we have provided policy recommendations that the government can consider implementing to allow people from these segments to overcome the challenges.

Interoperability and shared agent networks

Perspectives on shared agent networks from emerging economies

When you visit an agent outlet in Kenya, you often see a number of point-of-sales devices being used by the agent. When you enquire about it, she would mention that each of these devices belong to a different bank. Using this maze of devices, she serves a number of customers from different banks that visit her. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, agents are coping with reduced business and extra costs due to the curfews, social distancing and hygiene, and reduced hours of bank opening. However, one must ponder upon how complicated it must be for her to manage transactions with each of these banks, maintain float to service the customers from different banks, and keep a stock of how much she is making from these transactions.

Building and managing a robust agent network is one of the most difficult tasks for digital financial service providers. Managing distribution through a network of agents across the different areas in a country is an expensive affair. Considering the complexities of building and managing sustainable agent networks, providers have started to collaborate to share resources on agent network management. An innovative business model that reduces the cost of managing agent networks and enhancing reach for providers is the shared agent network.

A shared agent network is an approach that allows several financial service providers to share agency banking infrastructure and technology to serve the customers. A customer of one bank can thus use an agent established by another bank or financial institution.

A shared agent network enables banks to ride on shared infrastructure to expand services to a wider geography and a larger set of customers. It helps rationalize the costs associated with establishing agents across vast operational areas. It also helps to realize the investments from setting up an agency, recruiting and training agents, and managing the agent network. These investments enhance financial inclusion on account of spread and penetration of digital financial services.

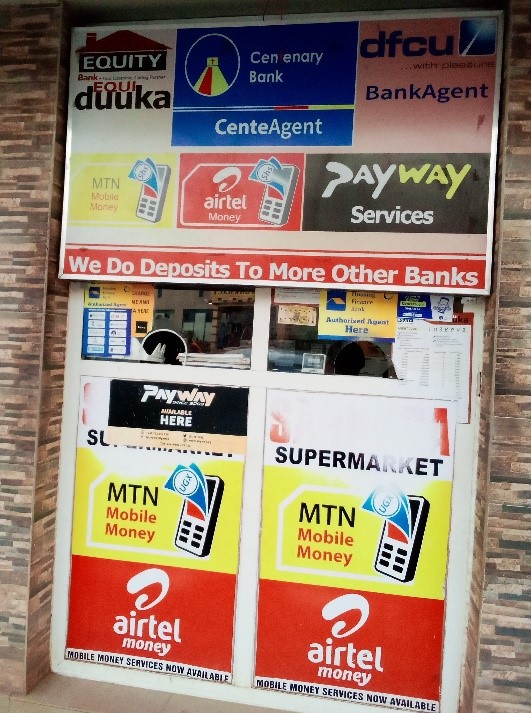

Image 1: An informal shared agent outlet in Machakos, Kenya. Photo courtesy: Christopher Blackburn

There are two different forms of shared agent networks:

- Formal shared agent networks as exhibited in Uganda (Agent Banking Company – ABC), Nigeria (Shared Agent Network Expansion Facilities

– SANEF) and India (Eko India Financial Services): These are agent networks that are set up to serve several providers through a common network manager.

– SANEF) and India (Eko India Financial Services): These are agent networks that are set up to serve several providers through a common network manager. - Informal shared agent networks as exhibited in Kenya and Pakistan: These are really just agents aggregating and offering services from a variety of providers. Clients either have to transact through one of several providers they have accounts with as is the case in Kenya. Clients can select one from many providers who they do not have to have accounts with in order to transact – as is the case in Pakistan.

Informal shared agent networks came about through organic growth of agent distribution points in ecosystems where agents are by design not expected to provide services of only one provider. Markets such as Kenya and Pakistan have had a relatively longer history of providing an enabling environment for agents to avail services from different financial service providers in a competitive manner.

Individual agents in an informal shared agent network may however lack some of the advantages provided to the formal shared agents, key among them is the ability to manage several interoperable[1] float accounts. Despite lack of such capacity, informal shared agent networks have flourished in early adopting markets of agent banking. In Kenya, for example, some agents provide services of up to 11 financial service providers, with separate devices, record keeping, and float management.

Formal shared agent networks are being adopted in markets where agent banking is steadily picking up through agent network management of several financial service providers offerings by third parties. These third parties are either privately owned or promoted by industry associations. Such institutions are considered to have the professional capacity to manage and expand distribution networks on behalf of FSPs while saving management costs. There has been significant success of this model in some markets where these third parties began by managing agent networks of a single institution and gradually adding the number of institutions that they serve. Eko in India has partnerships with multiple banks where each agent outlet offers services from several banks. Formal shared agent networks sponsored by industry associations like SANEF in Nigeria and ABC in Uganda are yet to realize as much comparative success.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (Banking and Payments Systems Directorate) through the Bankers’ Committee and in collaboration with all banks, mobile money operators, and super agents in Nigeria launched Shared Agent Network Expansion Facility in 2018 that has an ambitious goal of reaching out to 50 million Nigerians by 2020 through a network of 500,000 agents. These targets have been further divided across the geopolitical zones to have equitable growth of the agent network. To enable this network, CBN has earmarked soft loans quantum to be disbursed to the providers selected basis their experience, staff strength, spread etc.

Shared agent networks help providers to reduce the cost of platform management and maintenance, agent training and monitoring, as well as improved liquidity management – particularly in fully interoperable environments. Formal shared agent networks however need considerable concerted effort to expand the network and equitably manage the interests of all service providers. While some markets have embraced shared agent networks, regulators in other markets prefer to hold only regulated financial institutions as accountable for agent performance, and hence are not amenable to the idea of shared agents.

We believe that as digital financial services mature, providers should compete on product rather than channel. Some providers argue that opening up the entire agent network may bring certain disadvantages such as customers not receiving proper and professional service. An approach for providers to create the differentiation amongst the agents would be focus on two differentiated levels of agents, a sales agent and a service agent. The few exclusive sales agents may focus on product sales, account opening, customer on-boarding, and large-value transactions. These would then be complemented by large numbers of shared service agents servicing a range of providers by conducting small cash in or cash out transactions.

[1] Interoperability of float accounts is the practice of managing float from different FSPs using a common platform thus enabling an agent to service all FSP customers using a single liquidity pool.

The shared agent network in Uganda

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the income for both rural- and urban-based agents has significantly reduced in Uganda because the transactions have significantly reduced. Customers cannot travel due to the travel restrictions and they are not transacting as much. With the advent of shared agent network, Ugandans can now easily access banking services irrespective of which agents they visit. These agents can serve customers from several institutions and are able to do more business.

In January 2016, the Ugandan Parliament approved the Financial Institutions Act (Amendment) 2016 and thus

paved the way for agency banking in Uganda. Furthermore, with the advent of shared agent network Ugandans can now easily access agency banking services irrespective of which providers’ agents they visit.

paved the way for agency banking in Uganda. Furthermore, with the advent of shared agent network Ugandans can now easily access agency banking services irrespective of which providers’ agents they visit.

Considering the massive investment required to set up and manage agency banking structures, Ugandan Banks – under their umbrella association – the Uganda Bankers’ Association (UBA) – agreed to set up a shared agency network. The shared agent network operates on a platform jointly owned by the UBA and Eclectics International (a technology service provider) and managed by the Agent Banking Company (ABC).

As of February 2020, 13 banks[1] are on ABC’s shared agent platform. As at September 2019, there were 9,477 shared agents spread across the country. These agents facilitated an average of 2.15 million transactions monthly. Agents on the shared platform can facilitate deposits, withdrawals, utility bill payment, open accounts, do balance inquiries, provide mini statements, and handle school fees payments.

Benefits of the shared agent network

The key benefit for the participating banks that shared agent networks bring is the cost-saving. The banks have saved on the investment required to set up their individual agent networks. The costs of setting up and managing agent networks include the hardware (point-of-sale devices, smartphones, and blue tooth printers), recruitment and onboarding, and training.

customer fees of shared agent network

The shared agent network in Uganda rides on existing networks of some of the largest financial service providers (in terms of outreach in the market) and hence is able to expand the network’s presence and increase transactions. In addition, the agents benefit from simpler float management. Agents can now rebalance at any bank branch at a cost which is 30% of the regular cash withdrawal fee, regardless of whether the transaction was a withdrawal or deposit. Float re-balancing is an extra income stream that encourages the banks to open up their branches to agents of other banks.

Through the agency banking channel, banks have managed to push basic transactions out of, and thus reduce congestion at, their branches. In an interview with NBS Television in 2019, the Head of Agent Banking at Stanbic Bank, Ronald Muganzi mentioned that 85% of the basic transactions at Stanbic are now happening outside the branches. This is partly attributed to being on the shared platform.

Some of the agents who had agency banking as a secondary business mentioned that they benefit doubly from the shared agent network. Their income streams increased through earning extra commission and they have also increased sales of other products from their primary businesses.

The customers, on the other hand, are particularly happy as the shared platform makes banking pleasant and convenient. In addition, they can receive services not just from the agent of their bank, but an agent from another bank.

Challenges facing the shared agent network

In an ideal scenario, on a shared agent platform, an agent should have just one point-of-sales device. However, since some banks have not yet signed onto the platform, there are still multiple devices from different providers deployed at the agent points. Nonetheless, given the complexities of managing the shared agent network device as well as devices of banks that are not on the shared network, some agents have decided to have only one device and their choice is determined by the most responsive bank.

We found that several agents, despite being on a shared agent platform, still hold more than one point-of-sales device as even the banks on the shared platform continue to supply them with their own machines. This could be attributed to the fight amongst banks for visibility amongst the agents and to let their customers avoid extra charges incurred from transacting through another bank’s agent.

During busy transactional banking seasons such as at the beginning of the school term, the system may go off-line or slow down significantly due to increased demand. In such instances, customers have to use other options available to them to transact. Some agents mention that they are hesitant to operate with just one machine on a shared platform on account of unreliable network and downtimes.

Some of the financial service providers feel that they lack control over pricing. They feel that the bigger banks on the platform influence pricing and they have no option but to follow. To understand this problem, consider the scenario explained below.

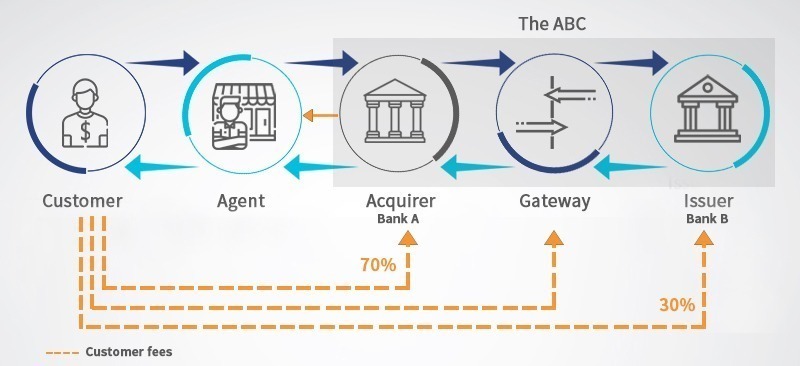

Figure 1: Illustration of the distribution of customer fees between stakeholders of the shared agent network

Inferences from the above illustration are;

- In the shared agency network, the issuer bank (bank hosting customer account) pays 70% of the transaction fees collected from the customer to the acquirer bank (bank owning agent point)

- Of the 70% of the transaction fees earned, the acquirer pays a small percentage to the agent as commissions and keeps the remaining to meet the costs such as paper rolls, branding materials, as well as their profit margin

- The issuer on the other hand, whose customer did the transaction, gets 30% of the transaction fee. From this 30%, it pays half to ABC. Consequently, the issuer receives 15% of the transaction fee.

As we can see from the description, the acquirer bank enjoys the largest share from the transaction fee. It is worth noting that the transaction fee that will be charged is decided by the issuer bank, who owns the customer. Thus, the smaller banks feel that such pricing approach favors that are often the acquirers due to their relatively larger agent networks. The decision on this percentage split was deliberate to favor acquirer banks in order to encourage bigger banks with larger existing agent networks to join the platform.

All financial products offered on the platform must be approved by ABC. Some of the financial service providers feel that the implementation of innovative ideas on the platform is limited by this requirement.

Lessons learned

The shared agent network in Uganda is still fairly young and the experiences of the FSPs and customers are still evolving. The stakeholders are addressing the challenges encountered as they come along. A few lessons learned so far include:

- Banks need to have uniform approaches to pricing. A bank that does not charge, or charges significantly lower, fees when its customers use its own agents, and charge higher for its customers to use agents of other banks will discourage the use of the shared agent platform. In such a scenario, the reconciliation for agents becomes much more complicated as they manage more than one single float account for the same bank.

- Pricing of a shared agent network is a complicated matter that should be carefully handled to provide financial services responsibly. Often providers complain of the uniform pricing structure as they have different cost structures. Thus, pricing is a delicate balance between what is reasonable to customers and what adequately compensates the banks and agents.

- Unless the banks feel that they own the model, there would be lower enthusiasm with which the shared agent network is embraced. In the case of Uganda, through the UBA, there is a perception that the banks collectively own the model, which motivates them to ensure that it succeeds.

- Excellent customer service is key to the success of a shared agent network. The agents have to be well recruited and trained. The banks are required to recruit agents that meet the set standards prescribed by the BoU. The agents are expected to be courteous and professional as well as follow the laid-out procedures to ensure consumer protection. Some of the measures put in place include refusal of the agents to conduct offline transactions, PIN authentication by both agent and customer for transaction approval, amongst others.

- There is a high likelihood of fraud being perpetrated on the platform due to the extension of several institutions’ and their customers’ information to third parties (agents). Prudent measures to strengthen data privacy through redaction of customer information that remains with agents is critical to preventing fraud.

According to the Finscope survey, 2018, only 58% of the Ugandan adult population own a bank account. This shows that there is a huge potential for growth. The ability of the agents and financial service providers on the shared platform to market the various accounts sold by the banks will be critical to ensuring that every Ugandan adult has a functional bank account. Overall, even though the COVID-19 pandemic has slowed down the progress being made due to the lockdowns instituted to manage the spread of the virus, agent banking in Uganda is headed in the right direction. ABC is in the process of revising its standard business rules that will govern all the banks on the platform. These revisions aim to harmonize and standardize the user experience, review the pricing regime as well as revamp the scheme rules to better manage the role of banks and agents in offering ubiquitous financial services in a responsible manner.

[1] Stanbic, Absa, Bank of Africa, Diamond Trust Bank, DFCU, Housing Finance, Post Bank, Opportunity Bank, Centenary Bank, Tropical Bank, Finance Trust Bank, United Bank of Africa and Exim Bank

Not Just Another Startup Accelerator in India: How the Financial Inclusion Lab is Shining a Light on Underserved Customers

India today has an accelerator for almost every domain, ranging from fintechs to the Internet of Things (IoT), from healthcare to consumer retail. You name it, we have it. It often seems that there is an accelerator in every corner of India’s major cities, with a new one springing up every month.

So why am I writing an article on another incubator/accelerator in India’s fintech domain?

The reason is that many accelerators face a common shortcoming: inclusivity. So when an accelerator comes along that addresses that issue, it’s worth noting.

The Indian fintech ecosystem has still not been able to reach underserved communities, especially the low- to medium-income (LMI) population of the country—households that earn between US $2-10 daily, with volatile and unpredictable incomes. A huge digital divide plagues our society, and few seem to care about it.

We at MSC decided to take it upon ourselves to create an impactful support system to boost the nation’s progress toward financial inclusion, and build a legacy that relevant ecosystems in India and other countries can benefit from. To that end, MSC conducted an intensive landscape study on the startup ecosystem to determine the type of support that could be given to startups to strengthen the financial inclusion movement in India.

As a result of these deliberations, the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad’s Centre for Innovation Incubation and Entrepreneurship (CIIE.CO) set up the Financial Inclusion (FI) Lab under the Bharat Inclusion Initiative in 2018, with MSC as a partner.

Lessons Learned from the FI Lab so far

The Lab offers a holistic package of support for each startup, ranging from mentor hours and grant capital to field studies led by financial inclusion experts for consumer and market insights. Since its inception, the Lab has successfully supported 18 startups across two cohorts and is currently running the third cohort of startups. These startups are from diverse domains of financial services, from savings to insurance to agri-finance. The infographic below depicts the combined impact of our lab.

While these numbers appear quite impressive, serving these startups has been challenging. In the process, we have learned six lessons about how best to provide technical assistance to them. We have also learned or reinforced three fundamental lessons for the ecosystem.

No one-size-fits-all solution: One-size-fits-all solutions will not work across the LMI segment. To take just one example, one might expect that women self-help groups (SHGs) would share enough similarities across geographies that a standardized approach could work for them all. But in Pune’s suburbs, these SHGs’ members can pay their households’ dues using smartphones and mobile apps. On the other hand, many SHGs in Rajasthan’s towns include users who only own basic feature phones. This means that an intuitive mobile solution designed for Pune’s SHG customers may be too complex for Rajasthan’s SHGs.

Beware of copy-paste solutions: Most of the startups building solutions for the LMI segment simply extend the solutions they’ve developed for urban, tech-savvy folks—a classic copy-paste approach. For instance, so many Indian mobile apps use a “shopping cart” icon, which blue-collar factory workers or people living in tier–II cities who have never seen a supermarket or a cart cannot relate to or identify.

Founder participation in Lab activities helps them build faster, superior solutions: The Lab was able to give its startups a deeper understanding of the LMI segment, and challenge their solutions and their applicability to LMI customers. This provided new understanding – and prompted new thinking – among many of our enterprises. For instance, the EasyPlan founding team, during its participation in the Lab’s field research activities (such as customer interviews and market surveys), realized that its solution was not a fit for its target customer segment. It quickly adapted to build a new product-market fit for a new LMI customer segment that would buy its products willingly.

How the Lab is Unique?

There are several reasons why the Lab’s approach is uniquely suited to helping startups serve LMI customers.

We start from where others have left off: Many startups and accelerators stop at the point of creating a product or service they think will serve the LMI segment and fulfill the objective of financial inclusion. For us, that’s just the starting point. Once these products and services have been created, we work with startups to help them customize and implement their solutions with their LMI customers. For example, Navana Tech builds a text-free, image-based and voice-enabled software development kit (SDK) for the LMI segment. Navana Tech’s clients build intuitive, user-friendly mobile apps leveraging this SDK to cater to their LMI end customers, such as smallholder farmers, micro-loan borrowers, etc. We helped Navana Tech build image-based mobile applications by validating their mobile user interfaces with actual target end-users.

We support startups to support themselves: While most of today’s accelerators have become intermediaries that merely connect startups to venture capital funds, we believe that startups should first be mentored to build self-sustainable businesses that will become investable.

We understand the LMI segment: period: Many fintech accelerators focus on financial inclusion but have limited knowledge about the nuances of the LMI segment. Since this population comprises the core customer segment for financial inclusion, these accelerators are unable to provide the required support. All the startups from our cohort believe that by working with us, their understanding and sensitivity towards this segment has increased manifold.

Credibility is the name of the game: We have brought together credible partners and CSR grant money. Additionally, a high-level advisory and steering committee has provided further credibility, along with helping startups avoid any regulatory pitfalls. As a result, joining the Lab signals that they are a part of an authentic portfolio of impact investors. This has helped many of them to raise funds more easily.

Gender diversity: We are proud to support startups that are led by women founders. This shows in the rich mix of our selected startups, wherein more than a third of them have women co-founders. The “ladies in the lead” hold the mantle of their respective businesses through their roles as chief executives to chief marketing to chief technology officers.

The Lab actively promotes India’s technology infrastructure: India Stack, the world’s largest application programming interface (API), helps startups reduce the development costs for APIs by 90%, as compared to developing or using other commercial APIs. The Lab also mentors and supports its startups in utilizing this infrastructure, and helps to strengthen it through more avenues of innovation by building a diverse range of solutions on top of the stack.

FI Lab’s response to the Covid-19 Pandemic

As I write this article, the COVID-19 crisis has started to affect India’s startup community badly. In brief, these are some of the major challenges facing the country’s startups as the pandemic unfolds:

- They have had to completely shut down field operations, including onboarding new customers through physical visits.

- Their revenue streams have shrunk, because customers are delaying or even refusing payments.

- Their suppliers have started asking for pre-payments, and have stopped giving credit.

- There is no government or regulatory support ready yet for fintech startups.

- Startups are looking at cost-cutting measures more actively than ever.

MSC and the Centre for Innovation Incubation and Entrepreneurship have been modifying our approach to offering high-touch support to help the Lab’s startups navigate these troubled times. Some of the measures that we have initiated already include:

- Maintaining the flow of field-based insights to startups by re-working our strategy of conducting research — from on-site field research exercises to telephonic and remote interviews.

- Coaching startups to automate their internal processes and digitize communication channels with end customers.

- Building short-term (1-4 months) and medium-term (4-8 months) contingency plans and strategic roadmaps for startups

The Lab’s evolving focus for Fintech in India

As mobile technologies and better information systems can bring more LMI segments into the realm of financial inclusion, we believe that India’s new wave of fintechs should start focusing more aggressively on building products and services that will empower these customers to take the following actions, as outlined in the infographic below.

We firmly believe that by engaging with fintech and providing them with relevant inputs, we can create impactful solutions together to serve the financially excluded and build a better, less digitally divided society for the benefit of all.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that are making a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat

This blog was also published on Next Billion on 15th of June, 2020

Bridge2Capital and Navana: Seniors of the batch!

This blog is about a startup in the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world – Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation and Omidyar Network.

Brothers Raoul and Jai Nanavati started Navana Tech in 2018 from their study room. At around the same time, Mohammed Riaz and Nishant Singh left their senior positions in well-established companies to pursue their entrepreneurial ambitions, which bore fruit as Bridge2Capital. Today, while Navana Tech is a part of the elite list of top 30 tech startups in India, Bridge2Capital has been shortlisted as one of the most promising fintech startups by India Fintech Awards Association.

Bridge2Capital and Navana have been with the Lab since the first cohort. In a way, the Lab and both the startups have grown together since day one.

Though they are from the same cohort, the founding teams are quite a contrast to each other. Bridge2Capital comprises veterans who have deep and vast experience in the rural distribution space in India. On the contrary, Navana Tech comprises younger blood and recent Cornell graduates who seek to build software for the low-literate and low-income groups of India. Yet their passion to serve the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segment that remains vastly underserved is a common bond that ties them and our Lab together.

Bridge2Capital’s journey so far

Bridge2Capital started with a simple idea: to support local mom-and-pop stores, or Kirana stores as they are known in India, to turn their inventory over in the most productive way. These stores usually depend on supplier credit to stock inventories and sell to customers. They do not have much in terms of credit history as they deal in cash, which does not leave a digital or a paper trail. Hence, they are mostly unable to provide sufficient proof of their business flows and get loans from formal financial institutions to expand and grow. Bridge2Capital solves this problem by financing these small shopkeepers based on GST-authenticated supplier invoices.

Though Bridge2Capital was doing quite well at the end of the first cohort, it was able to muster only around 200 odd shops from three to four tier-II and III Indian cities on its platform. You can read about Bridge2Capital and its business model in our previous series on cohort 1. Now, after the second cohort concluded, Bridge2Capital has on-boarded more than 1,000 shopkeepers across 18 tier-II and III cities of India on its platform.

What made it happen?

A few factors contributed to this:

- Resilience: The Bridge2Capital team kept on going to different kinds of shops to collect data, such as the size of the shop, history of existence, and information about the shopkeeper. The team tested each cohort of shops and shopkeepers carefully with small loan sizes. They failed many times in those pilots, but with each failure, they learned what not to do and made sure they did not repeat their mistakes.

- Business intelligence: The founding team has built a data-centric culture in the startup. The on-field teams collected data methodically and objectively and paid equal attention to organizing it. This allowed Bridge2Capital to utilize the data quickly, to run nimble experiments, and to select and persist with the right kind of shopkeepers—ones who could and would pay them at regular intervals with minimum interventions.

- Thinking ahead: Startups need to evolve continually—not only to stay ahead of the competition but also to stay motivated and dream of bigger achievements. Like many other credit-underwriting fintechs that use alternate data, Bridge2Capital had built a robust algorithm to generate a reliability score based on the payment history of each of its onboarded shopkeepers.

However, it realized that the market lacked a technique to ascertain the intent of the shopkeeper or borrower in general to pay their dues.

Therefore, Bridge2Capital started to explore other methods, such as behavioral analysis and psychometric evaluations to see how these can be combined with its existing credit underwriting algorithms, to produce even better and more reliable predictable scores for existing and new shopkeepers.

The Lab supported Bridge2Capital in becoming more efficient and productive

The Lab helped the startup team through a mix of academic and pragmatic approaches. The boot camps and classroom sessions took an academic approach to build a business, while the field surveys, market research exercises, and data analysis defined and delivered a practical approach to lending. The support allowed Bridge2Capital to:

- Lower its customer acquisition costs by identifying and overcoming inefficiencies in the customer onboarding process.

- Experiment with newer ideas to enhance business productivity and learn what it should not do.

Helping shopkeepers in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic

Empathizing with its customers, the shopkeepers, Bridge2Capital has introduced the following measures to ease the financial hardships caused by this pandemic:

- It has allowed its shopkeepers to convert their short-term loans (payable within a month or two months) into longer-term loans that span six to 12 months, by paying up a small conversion fee.

- It has allowed Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) three-month moratorium on the repayments for its shopkeepers. Many shopkeepers are still willingly paying the interest part of their borrowings during this period.

- It has introduced a new product, Bridge2Pay to enable its shopkeepers to receive payments in a “presence less” mode, to maintain social distancing. The shopkeeper uses WhatsApp to forward a unique QR code generated by Bridge2Capital to its customers. This helps the customer to just scan the code through their mobile phones and pay the shopkeeper through Unified Payment Interface (UPI).

Navana Tech: Adapt-as-you-go

You already know about Navana Tech from our previous blog series, so we will talk about what the brothers, Raoul and Jai, have been up to since then. From the beginning of the first cohort until today, Navana Tech has continued to pivot its product ideas. It started from an operating system (OS) layer over Android OS and moved to a simpler, text-light, image-based phonebook app, from which it transitioned to a software development kit (SDK). The SDK allows businesses, especially banks, to build mobile applications for the illiterate and semi-literate populations of the country.

One constant for the company has been its steadfast focus on serving the community of users who form a bulk of the LMI segment of our country. It has a deep understanding of the user experience of its customer segment and has expertise in building intuitive user interfaces for them. This has earned it a place among other promising startups of not only the FI Lab but also among the Microsoft for Startups program.

Today, Navana Tech partners with prominent microfinance institutions (MFIs) and small finance banks (SFBs), such as Ujjivan and Shubh Loans. These institutions serve the LMI segment across the country by lending to them at reasonable interest rates. However, these MFIs and SFBs faced challenges in transforming their manual, paper-driven processes of a regular bank to automated, digital, and more user-friendly processes. Navana is helping them do that today.

Navana Tech has also recently gone beyond the financial services domain and started running pilots with Digital Green to help it develop hyper-local mobile applications. The applications allow small landholder farmers to become entrepreneurs, who in turn recruit other farmers and sell their collective produce to suitable marketplaces nearby.

Navana Tech created a user interface (UI) that uses voice and natural language processing (NLP) to “hear” and “understand” what a customer speaks in their local languages. By doing this, Navana Tech is breaking a pivotal barrier that can help bring the LMI segment into the fold of regular smartphone users who perform a variety of tasks, such as mobile banking from the place of their choice.

The start-up’s team continues to run pilots with these institutions and enrich its database to build robust solutions that can serve a range of people who speak different dialects.

The team started with barely a minimum viable product (MVP) with no clients at the beginning of the first cohort, with both the founders working from their homes in Mumbai. Today, Navana Tech has moved to a formal office space in Whitefield, Bengaluru. It employs a team of nine, with three clients: Ujjivan, Shubh Loans, and Digital Green in its kitty.

Navana has shown the following attributes as it grew its business:

- Agile mindset: The team led by the brothers, developed its software in multiple, short iterations by continually testing it with their pilot customers and feeding their concerns into making better designs.

- Open to new ideas: The Navana team has not confined itself solely to the domain of financial services. Today, it works with Digital Green, an agri-services provider, and intends to work with a few healthcare companies that cater to the LMI segment.

- Passion and knowing when to say no: Despite having some lucrative opportunities after graduate school, the brothers stuck to their plan and refused to take up opportunities that could have diverted them from their vision of serving semi-literate and illiterate people.

Surviving the pandemic

The COVID-19 situation has been particularly harsh for Indian startups. The payments that existing clients owe them are delayed, and no new clients are willing to give business. Given this, the Navana Tech team has been taking the following measures to survive:

- The startup has reduced its variable costs by switching to cheaper tools for software product development.

- It has initiated conversations with prospective clients, including non-financial service providers, and offered them freemium versions. The terms of payment for these versions are flexible and the clients can opt-out at any time. This strategy has strengthened its sales pipeline.

Way forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on startups like Bridge2Capital and Navana Tech. Their short-term goals for growth have been deferred. However, both teams have been quick to adapt to the situation. Their immediate plans are to survive through the next 3-6 months by staying lean in terms of staff-strength and nimble in terms of strategy and implementation to adapt to the rapidly changing business environment. They have plans to consolidate their businesses with their existing clients or customers, build more digital features in their products, and keep their team’s morale high.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that are making a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat