Women agents provide great customer service. They are more attentive, helpful, diligent, and effective at building trust. They are also better at on-boarding women and other underserved populations than their male counterparts. These are often cited conclusions from a series of qualitative studies in India, Zambia, and other markets across Asia and Africa. At the same time, we still lack the hard data to inform the business case for women agents and implement any adjustments to agent network management strategies for this segment.

Women agents provide great customer service. They are more attentive, helpful, diligent, and effective at building trust. They are also better at on-boarding women and other underserved populations than their male counterparts. These are often cited conclusions from a series of qualitative studies in India, Zambia, and other markets across Asia and Africa. At the same time, we still lack the hard data to inform the business case for women agents and implement any adjustments to agent network management strategies for this segment.

The Helix Institute of Digital Finance has conducted nationally representative Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) surveys of mobile money agents in eight leading DFS markets. This blog draws on this rich source of data to answer the following questions: How well are women represented in agent networks? How do they compare to male agents? What specific constraints do they face? How can providers ensure that women agents succeed, as the qualitative research would suggest?

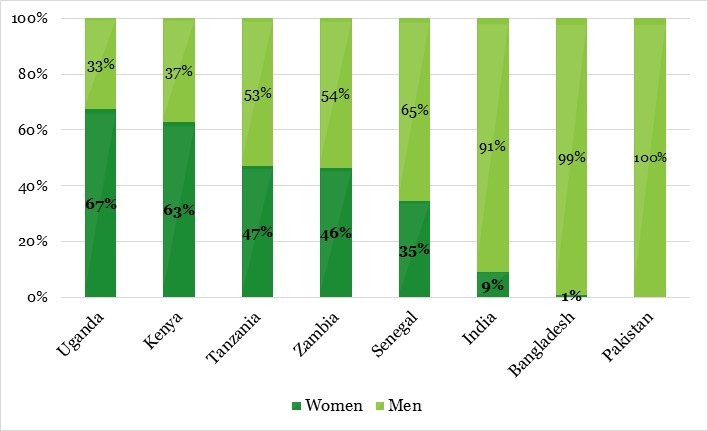

Women are Severely Underrepresented in South Asia

The contrast between female representation in Africa and South Asia is striking (Figure 1). The absence of women from agent networks in South Asia stems from cultural barriers and socio-economic constraints. Women have limited access to public spaces, identification documents, bank accounts, mobile phones, and economic activity more generally.

Figure 1. Agent Network Gender Makeup

Source: Compiled from the Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Surveys. The figure contains most recent data available.

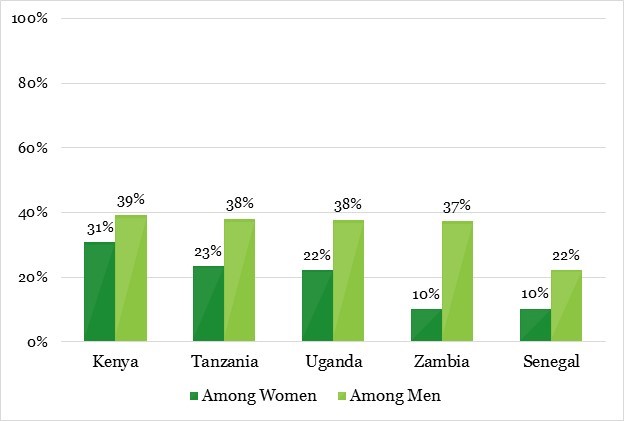

While women in Africa also face socio-economic barriers, they are better represented in agent networks in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia and Senegal. They are just as educated as their male peers and are similarly distributed across rural and urban areas. They also largely serve the same providers and run similar parallel businesses, such as general stores and airtime retails. However, women have fewer years of experience as agents, indicating that they entered the DFS markets later than men. Moreover, a much lower proportion of women agents own the mobile money business (Figure 2).

Why do Few Women Own Mobile Money Businesses in Africa?

Institutionalised gender constraints help explain low female ownership rates of DFS businesses. Women across markets are less likely to have an account at a formal financial institution. They constitute a mere 24% of formal SMEs owners in Sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, providers’ agent selection criteria often include having a bank account, a registered business as well as a minimum capital requirement. For this reason, operating largely in the informal sector, with low start-up capital, little collateral, and limited access to finance makes it difficult for women to fit providers’ desired agent profile. As a result, few women-owned businesses are recruited as agents.

Figure 2. Percentage of Agents Who Own the DFS Business

Source: Compiled from Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Surveys. The figure contains most recent data available.

Women’s Constraints in East African Wallet Markets

ANA data shows that in Senegal and Zambia, agents conduct similar business volumes, regardless of gender. However, in East African wallet-based markets (EAC), women perform on average four to five (9-17%) less daily transactions than men, irrespective of whether they own or operate the DFS business. This translates into lower revenues for their businesses. While further research is needed to better understand all the factors that explain women’s lower business volumes, our data can offer a few explanations:

- Although women manage their liquidity needs (e-float/cash) just as well*, if not better than men do, they have less working capital to conduct transactions. On any given day, women report holding 10-30% less cash and e-float across three EAC markets.

- Women generally work fewer hours compared to men, though this gap varies between 3 and 7 hours per week across markets (4-9% of men’s operating hours). Shorter operating hours mean foregone business.

- Although they are just as likely to receive initial training as men, a greater proportion of women are trained by their employers or master agents. This may have implications for the quality and depth of the material covered and the resulting agent performance.

- Women are less likely to offer account opening/activation services, which affects the overall transaction volume and may hinder their ability to build a customer base.

Building the Business Case: What are the Opportunities?

Our analysis reveals that in Africa, women agents face serious structural constraints, hindering their success in the DFS business. If women are indeed better at customer interactions – particularly with late adopters and female customers, who are the next frontier of mobile money adoption, – then providers should consider proactively investing in the female segment of their network.

Experience shows that when providers pay attention and adoptprogressive and innovative agent models tailored to women, female agentssucceed. In Tanzania, where women owners report working with similar (91%) capital as men, they conduct just as many daily transactions. Similarly, in Zambia, where the front runner Zoona has focused on agents as their primary customers, providing credit facilities and high quality training, women agents also perform on par with men (39 and 35 daily transactions, respectively).

We recommend that first and foremost, providers invest in better understanding this segment of their agent network as it will become increasingly crucial for further business expansion. Challenges discussed in this blog – lack of capital, lower quality training and customer enrolment rates – could serve as a starting point.

In South Asia, providers will also need to think of creative ways that are culturally appropriate to integrate women into their networks, if they are to grow their female customer base. A follow up blog will delve deeper into these issues and constraints for the benefit of South Asia.

*Based on both the reported number and percentage of transactions denied every day due to lack of float.

.jpg)