Risk in Digital Financial Services (DFS) has the potential to derail the financial inclusion agenda. If not managed in time, it can reduce trust, resulting in a vicious cycle of poor uptake of products and services, poor profitability, and thus poor implementation. This paper presents the findings on three inter-related concepts – Risks, Customer Protection, and Financial Capability in DFS at both the customer and the agent level. The vulnerability context in which people operate directly influences the risk profile of the customers as well as the frontline agents. Most of the risks identified in this research were operational in nature and can be resolved relatively easily. However, their expression, in terms of service denials and potential manifestation of fraud, in an environment with limited financial capability and high level of trust of the agents, is potentially dangerous.

Blog

Behavioural Biases Affecting Buying Behaviour of Kerosene Consumers for Alternate Fuels

The Government of India is considering replacing kerosene with Direct Benefit Transfers (DBTs)of cash into consumers’ bank accounts. Under the proposed DBT model, consumers will receive a lump sum credited in their bank account equivalent to the value of kerosene subsidy currently paid by the government. In addition to reducing leakages, the government expects that DBTs may encourage consumers to shift from kerosene to cleaner alternate fuels(AF), such as solar energy and electricity (or battery-operated lights), for both lighting and cooking. MicroSave conducted exploratory research to understand the ‘enabling factors’ that might induce consumers to buy and use alternate fuel(s) in the event of DBT. The research specifically looked at: “What will make kerosene consumers use DBTs to buy alternate fuel(s)?” This note explores the fuel(s) buying behaviour of different types of consumers, and what behavioural biases come into play when they buy fuel(s). The Government of India is considering replacing kerosene with Direct Benefit Transfers (DBTs)of cash into consumers’ bank accounts. Under the proposed DBT model, consumers will receive a lump sum credited in their bank account equivalent to the value of kerosene subsidy currently paid by the government. In addition to reducing leakages, the government expects that DBTs may encourage consumers to shift from kerosene to cleaner alternate fuels(AF), such as solar energy and electricity (or battery-operated lights), for both lighting and cooking. MicroSave conducted exploratory research to understand the ‘enabling factors’ that might induce consumers to buy and use alternate fuel(s) in the event of DBT. The research specifically looked at: “What will make kerosene consumers use DBTs to buy alternate fuel(s)?” This note explores the fuel(s) buying behaviour of different types of consumers, and what behavioural biases come into play when they buy fuel(s).

The Ebb and Flow of Customer-Centricity in Financial Inclusion Part 3 – What Happened and Where Are We Today?

In the previous blog “The Ebb and Flow of Customer-Centricity in Financial Inclusion Part 2 – Beyond the Basics” we discussed the details of building a customer-centric, or market-led financial service provider – and the intricate jigsaw puzzle of skills, processes, incentives, planning and execution required to pull it off.

Results

Results

So, did all of our action research partners become client-centric, market leaders? Are clients in their countries receiving amazing customer service and great products? The truth is that some institutions are better at delivering client-centric products than others. As a result of the project our ten action research partners developed or refined 9 savings products and 11 loan products. At the end of 2007, when the project closed and MicroSave transformed into a consulting company, 373,705 customers had loans from our action research partners; the outstanding balances on these loans were $300 million; 2.5m people had savings accounts an overall outstanding balance of $530 million.

Over the same period MicroSave trained more than 51 Certified Service Providers and over 1,000 staff in marketing, R&D, operations and risk management departments. Many of these people remain in the industry (if not in the same jobs). These people and institutions have a deep understanding of being “market-led” and we need to build on the talent and experience the industry already has.

We have all seen great research on what clients want and need and we’ve seen some really great innovations in being able to deliver simple products and to design great products that use behaviour and psychology to encourage client success. What we haven’t seen is many of these great designs reaching scale. The reality is that the difficult part of delivering great products that truly help clients meet their needs and goals is in the hard, less-glamourous work of system and organisational change.

Where are we today?

Some of our partners “stopped” being market-led when the MicroSave team, or the CEO or product champion left. Being a client-centric organisation is a supply side strategic choice – and it is an ongoing business practice. It requires constant attention, just like keeping up with IT, regulations, financial performance.

Being market-led or customer centric is not a project. It is not a BE class, nor a donor-funded HCD exercise, nor one department. It’s a continuous process of acting and reacting to the market, to the products your competitors are offering your clients, to the complaints and desires of your customers; and to your numbers. It is all about using your data to measure not just your bottom line, but to understand client behaviour. It is about a commitment to constantly seek to understand your customers’ perceptions, needs and aspirations … as well as the elements of your services with which they struggle … and to respond to these by changing processes, marketing and communication, staff training and incentives … and sometimes products. It is also about understanding customers at the economic and social level, and not to study them through product lenses. In fact, when we redefined microcredit years ago, and came up with microfinance, we painted microfinance as the four core products (transactional, savings, credit and insurance). In a way, we defined microfinance as a product approach, and took the focus away from the customer, the people we deemed as our target audience.

Recently Social Performance Management has begun to encompass many of the key essentials of a market-led and customer focused approach. SPM recognises that satisfied staff inspired by a clear, board and management-endorsed mission and strategy that is incentivised by remuneration systems rewarding a customer focus, are essential to achieve an effective social and financial bottom-line. Such a strategy must, of course, necessarily encompass appropriate products and delivery systems.

Given the recent renewed, and welcome, attention to client-centricity, complete with new acronyms (BE, HCD) and new tools (design thinking, financial diaries, GIS maps, big data, algorithms, rapid proto-typing), we thought we’d remind people that we as an industry are not starting from scratch! We’ve had experiences (good and bad) that we can build on to ensure that more and more financial institutions take a strategic rather than project approach and we really can serve the millions of people outside the financial mainstream.

We also want to remind ourselves that we have not yet arrived at the end of the journey, where customer centric financial service providers deliver great customer experience to customers who use the products and services. We still have to solve a few more challenges. How do you make the business case work? How do you ensure that we use a granular understanding of the economic and social lives of our customers and translate that into financial services that they continuously want to use? How do you empower customers to understand what you offer, to choose the right solution and to use it with confidence? How do you build trust between customer and financial service provider? Our understanding is that the concept of customer centricity as a supply side strategy is the right path to solve these challenges. However, we need to go deeper in embedding customer centricity as a business model in financial service providers. As mentioned, this means that we need to enter the worlds of organisational change, and the management of change. We need to learn from leading customer centric firms in other industries, and from trail blazers in the financial inclusion world. Indeed, the quest started by MicroSave and partners, many years ago, is far from complete.

This blog was first published at Center for Financial Inclusion

The Ebb and Flow of Customer-Centricity in Financial Inclusion Part 2 – Beyond the Basics

In the first part of this blog, we saw how just understanding customer demand is not enough to deliver mass financial inclusion … or even a successful product. Supply-side factors are key…if rather more difficult that a quick market research exercise. Even after careful pilot-testing and a structure roll-out, it turned out that all that preparation and keen balancing of client-desires and institutional capacity to deliver sustainably…didn’t necessarily work! Where were the clients? Why weren’t they storming the doors and asking for these wonderfully designed products? Weren’t our loan officers as excited as the project team? Did the CEO’s endorsement and great speech at the annual meeting make loan officers ready to sell the new products? Weren’t clients telling each other, and their cousins and friends?

No, they weren’t.

The supply side (staff) had not conveyed to the demand side (clients) that they had new products based on their feedback; they hadn’t convinced and trained staff, who were concerned that their jobs were about to get harder. Clients weren’t buying, and staff weren’t selling these new products. Once again, the action research partners attacked the issues and MicroSave worked alongside, frantically learning and documenting.

- Product Marketing. We quickly discovered that any idea of “offer it and they will come” was optimistic. Product marketing and communication are essential in making the product and its functionality known.

- Staff Incentives. Many FSPs did not offer staff incentives – or, rather, offered all staff the same incentives; or offered staff the “wrong” incentives. Paying incentives for no arrears led to some pretty poor customer service. Not paying incentives for savings, or for new products saw “orphan” products and a lack of attention to the customers’ full financial needs.

- Human Resource Management. To implement an effective staff incentive system of course required a systematic and robust human resource management system within which to operate. And as our partners grew, this need was further exacerbated particularly when trying to deliver high quality customer experience.

- Risk Management. New products bring change and new risks – at the operational and strategic level – so all a bit scary, particularly for organisations that have largely copied a tried and tested model as market-followers! New products bring not just process risks, but also regulatory and reputational risks, not to mention the obvious interest rate and credit risks. An approach to assessing and managing the risks involved in developing and introducing new products was also developed.

- Customer Service. By this stage, MicroSave’s action research partners were very focused on being customer responsive … and clear that this involved rather more than teaching their front-line staff to smile at their clients. This led to demand for a customer service toolkit to analyse and improve on all aspects of customer service. Now, with the emphasis on using agents, this is as relevant at the agent level.

- Corporate Brand and Identity. From sleeping dinosaurs to rampaging lions, our partners had many different brand positions in their markets. Recognising the power of brand to drive their business and attract the right customer segments, the action research partners also wanted a corporate brand and identity toolkit.

- Strategic Marketing. The action research partners had realised that all these disparate strands required a completely different approach to running their businesses – one that put the client at the very centre of everything.

Did this array of interventions yield the desired results? All will be revealed in “The Ebb and Flow of Customer-Centricity in Financial Inclusion Part 3 – What Happened and Where Are We Today?”

This blog was first published at Center for Financial Inclusion

The Ebb and Flow of Customer-Centricity in Financial Inclusion Part 1 – Why Being Customer-Centric is a Supply Side Strategy

In recent years Human Centred Design became a new focus area in the financial inclusion world. It focused financial service providers on the design of products and services based on customer insights. Design firms became part of the technical provider fraternity, servicing financial service providers in the quest to improved inclusion. At the same time, the definition of financial service providers broadened to include mobile network operators and retail chains, in addition to MFIs, banks, cooperatives and a myriad of MF suppliers. With new entrants come new ideas, and repetition of old ones. One consistent, but underrated idea, is to focus on the customer.

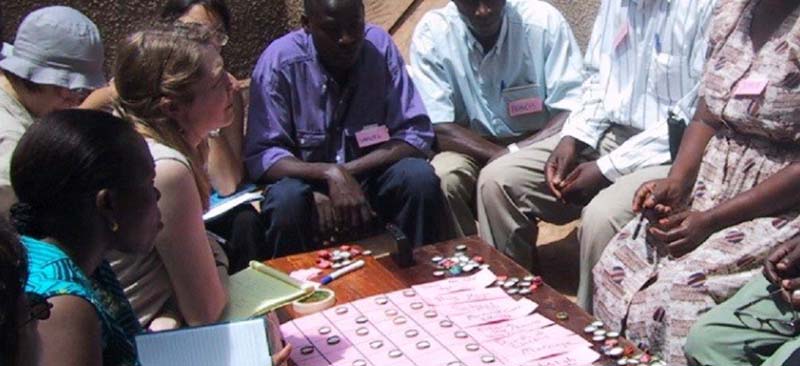

Customer centricity is not a new concept in the microfinance and financial inclusion world. In 1998, MicroSave was set up (by UNCDF/DFID who were then joined by CGAP, the Ford Foundation, and the Austrian and Norwegian governments) to promote savings in the microcredit landscape of East and Southern Africa. Initial research in Uganda, however, revealed microfinance institutions (MFIs) did not have a legal mandate to collect savings, but did have another problem: drop-outs as high as 60% per annum. Further investigation revealed that much of the problem lay in poorly designed credit products. Much of 1999 and 2000 was spent understanding the problem, re-designing products to mitigate it and developing the “market research for microfinance” tools and training. This resonates with the current realisation, that customers are not using products. This is evident in the GSMA research that found that 68 percent of registered mobile money customers, do less than one transaction in 90 days (GSMA, 2015). No frills accounts in India, and transactional accounts in many other settings, are mostly dormant (GAFIS, 2011). The market led research approaches of the “early” years, and the human centred design approaches of the recent years, did not fully succeed in focusing efforts on the customer, nor did it help to increase the use of financial products and services. In the quest to understand this we return to the unfolding story of the early years of market led approaches, based on the MicroSaveexperience.

MicroSave and its partners were quite pleased with the success of the client research and the new, in-depth understanding of their needs and wants. But, self-congratulations were cut short by the first mid-term review in 2000 (unpublished manuscript). Led by industry gurus Beth Rhyne and Marguerite Robinson – MicroSave was, rightly, chided for having focused entirely on the demand side and not addressing the importance of the supply side problems that needed to be solve to achieve real change.

The realisation was that any industry could not be “client-centric” without ensuring that the supply-side organisations who wanted to serve these customers were actually willing and able to serve them. Working with some of the more innovative financial institutions in East and Southern Africa, MicroSave spent the next seven years incorporating client responsive products within “market-led” institutions.

Being Customer-Centric is a Supply Side Strategy…

When one hears supply-side strategy, it conjures up deceptive marketing, product push, sell at all costs and finding new ways to make more money for managers and shareholders. Customer-centricity, we’ve heard lately, should be about researching and understanding the customer. But, is that enough? Being customer-centric must be a supply side strategy if we – this entire industry, including donors, consultants and retail financial services providers – really do want to deliver high-quality products that low-income people want to buy and use.

Conducting market research with clients had some excellent benefits beyond the product design. All of the MicroSave Action Researchpartners[1] required product champions and staff from throughout their organisations to participate in the research. Virtually all of them came away from the research with a much deeper appreciation of what their clients financial lives were actually like. It became very clear to loan officers that late payments were less a results of “stubbornness”, and more a result of a highly structured loan product that didn’t take into account farm cycles, or sickness, or school fees which needed to be paid before students were allowed to sit for exams. They also were amazed at the knowledge that clients had about microfinance, including what the competitors were offering and informal institutions. MFI staff were energised by the research and excited about designing new products. This is similar to the CGAP experience in supporting the HCD based work with financial institutions in seven countries in recent years. Managers and leaders who are engaging with clients gain understanding and insights beyond the mere reading of reports.

Conducting market research with clients had some excellent benefits beyond the product design. All of the MicroSave Action Researchpartners[1] required product champions and staff from throughout their organisations to participate in the research. Virtually all of them came away from the research with a much deeper appreciation of what their clients financial lives were actually like. It became very clear to loan officers that late payments were less a results of “stubbornness”, and more a result of a highly structured loan product that didn’t take into account farm cycles, or sickness, or school fees which needed to be paid before students were allowed to sit for exams. They also were amazed at the knowledge that clients had about microfinance, including what the competitors were offering and informal institutions. MFI staff were energised by the research and excited about designing new products. This is similar to the CGAP experience in supporting the HCD based work with financial institutions in seven countries in recent years. Managers and leaders who are engaging with clients gain understanding and insights beyond the mere reading of reports.

But, market research and being excited about it is the “easy” part in implementing customer-centric products! Actually delivering the products clients wanted required changes both large and small in:

- Planning, implementing and monitoring pilot-tests Systematically determining whether the new product met clients’ needs or was cost-effective for the institution to deliver was not done. Therefore, these new products were at risk for never being rolled out (CFOs questioned the business case), or not being “sold” (staff continue with the existing, understood, products).

- Costing and pricing Prior to being market-led, many of our institutions looked at their bottom line – not on a per product basis, or even a segmented client basis, but on a whole portfolio basis. Really focusing on the client meant our partners had to make trade-offs to offer what clients wanted, and what they could do at a low cost to serve. Costing and pricing models put all players on the same page, and lead to clearer choices when trade-offs do have to be made.

- Process mapping Efficiency is essential to keeping costs down and most institutions had managed towards efficiency – primarily in the form of group loans, fairly rigid loan-ladders, and as we see now, in the transactional world with a reliance on technology. Unfortunately, efficiency often flies in the face of customer-centricity: not everyone wants to borrow in a group, repay weekly and progress in loan amounts at the same pace as their neighbour. Not everyone wants to use their phone to bank. Process mapping tools helped FSP staff and the leadership see the entire process and enable client-centricity by being more efficient in back-offices and in ways clients may not see, in order to give clients the services they wanted and needed.

- Going to Scale Rolling-out new products and taking them to scale after the completion of a pilot-test is a difficult and complex process. Rollout is a multi-step process of moving a product from the successful conclusion of the pilot test, to the point where it is fully operational in all desired locations. A carefully planned rollout reduces risk of failure, allows you to organise resources and optimise their use, saves money and ensures full and effective management and staff buy-in.

In the next part of this blog, “The Ebb and Flow of Customer-Centricity in Financial Inclusion Part 2 – Beyond the Basics” we discuss what else was needed.

This blog was first published at Center for Financial Inclusion

[1] MicroSave’s action research partners included Equity Bank, Kenya Post Office Savings Bank, Centenary Bank, FINCA-Uganda/ Tanzania, Teba Bank, Tanzania Post Bank, Pride-Tanzania and Uganda Microfinance Union

Zambia’s comeback in digital financial services (DFS)

https://www.microsave.net/helix-institute/

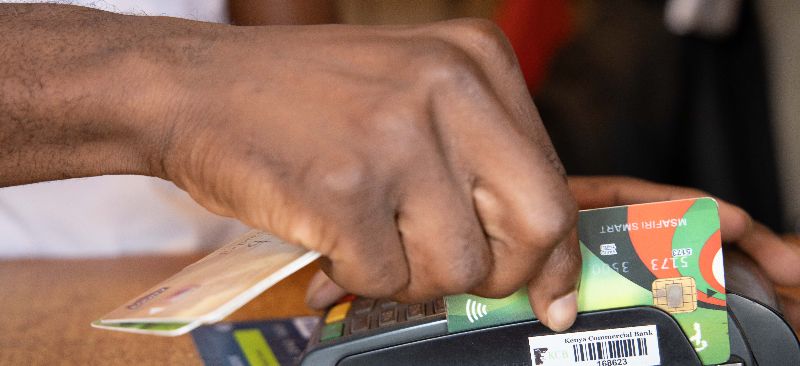

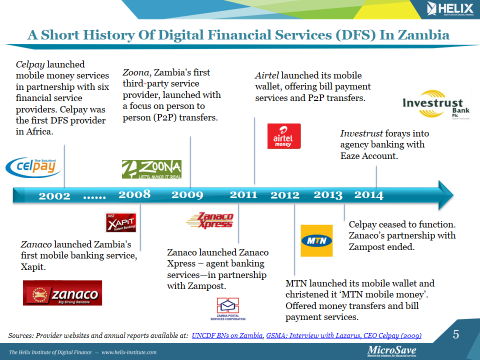

Zambia introduced Digital Financial Services (DFS) to the world with the launch of Celpay in 2002. Celpay’s offering to Zambians was somewhat similar to Safaricom’s ‘microfinance credit re-payment’ product, which was introduced in 2006 in Kenya. Whilst Safaricom’s M-PESA was able to spearhead the mobile money revolution by offering the value proposition ‘send money home,’ the Zambian market was not able to find this traction until 2009 when Zoona offered person to person transactions via the mobile platform (Figure 1)

Figure 1: A Timeline Of DFS In Zambia

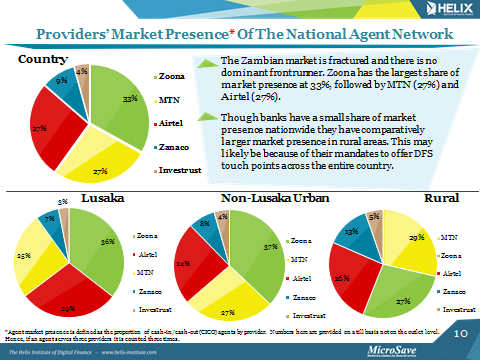

Fast forward six years: the Zambian DFS market is competitive; a diverse group of providers in the battleground claim approximately 4,500 agents across the country. The Helix Institute’s Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Survey in Zambia, which was funded by the UNCDF MM4P Programme and conducted between July and August 2015, interviewed more than 1,200 agents and provides evidence to support the fact that providers face a great deal of competition. Research on the market presence of agents indicates that the market is fractured into segments represented by banks, third party providers and telecoms companies and that there is no dominant frontrunner.

In fact, Zambia is one of the most competitive landscapes among ANA research countries with five providers in the mix, following Pakistan which has six providers that have 5% or greater market presence. In contrast, Bangladesh had four when surveyed in 2014 and the East African markets had three or less, with Kenya witnessing an aggressive expansion from the banking sector in 2015.

Zoona has the largest share of market presence at 33% (Figure 2), followed by MTN (27%) and Airtel (27%). Thus far, we have seen that the most successful providers in the digital finance space are telecoms companies, who have large marketing budgets plus national networks of existing retailers and typically millions of customers they can tempt to register for digital finance. Nevertheless a third-party provider has gained a lot of traction in Zambia; followed by telecoms, and by banks vying for a piece of the pie.

Figure 2: Providers’ Market Presence in Terms of Agents

Agents’ Transactions are Comparable to East Africa

It’s impressive that Zambian agents conduct transactions comparable to leading and mature East African markets—Tanzania and Uganda—at a median of 28 daily transactions. It is noteworthy that most of the transactions are focused on payment services—cash in/cash out, money transfer, and bill payments.

Yet curiously, less than half of agents offer account opening services, which limits a provider’s ability to expand its customer base. Indeed, agents cited the lack of awareness of services among customers as one of the top barriers to doing more business. This barrier points to a need for aggressive marketing from the provider. In fact, one-third of agents say that their provider’s marketing is not effective in increasing customers’ awareness of DFS.

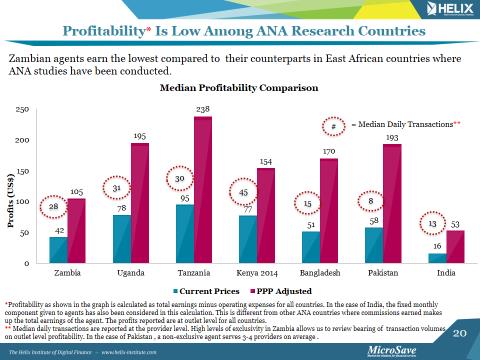

Profits Aren’t Aligned to Transaction Volumes

Whilst the number of transactions conducted is healthy, Zambian agents are not as profitable as their East African counterparts. In fact, profitability is among the lowest in ANA Research Countries (Figure 3). High agent profitability is often cited as one reason for the rapid growth of DFS in Tanzania. Agents in Zambia earn a median profit of USD$105 (PPP adjusted), compared with USD$195 in Uganda and USD$238 in Tanzania. It would be prudent for Zambian providers to understand the causes of low profitability among agents in order to avoid potential agent dormancy. The Helix research indicates that low earnings could be a result of the poor commission structures given to agents for low-value transactions.

Despite lower profits than East Africa, the current level of profitability is encouraging because:

- The market is nascent and the numbers of transactions are promising;

- Zambia is at a tipping point as only 14% of adults have/use mobile money, indicating a lot of room for growth;

- The competitive market may entice agents to work with multiple providers, thus increasing their potential revenue stream and profits.

Figure 3: Outlet Profitability among ANA Research Countries

The Future

The future could be very bright for DFS providers in Zambia. There are vast opportunities to expand financial access for Zambians, and the competitive landscape suggests a potential for the Zambian market to set new benchmarks in DFS globally. Financial services are ever more relevant to Zambians in the face of challenging financial circumstances. To set these new benchmarks, Zambian providers will need to revisit their strategies in order entice more Zambians to utilize DFS products, educate them on DFS services, and thus effectively breed the demand agents need to earn more profits.

Nandini is a Country Technical Specialist, responsible for the implementation of the United Nations Capital Development Fund Mobile Money for the Poor (MM4P) Digital Finance country strategy in Zambia. Partnering with Financial Sector Deepening Zambia (FSDZ), she is leading a team focused on increasing financial inclusion through digital finance. She is also assisting MM4P’s efforts in Malawi.