This presentation was conducted during the launch of our Tanzania Agent Network Accelerator report.

To read the report in full please click below:

This presentation was conducted during the launch of our Tanzania Agent Network Accelerator report.

To read the report in full please click below:

Governance has assumed increasing importance in the Indian microfinance sector over the last few years. With the growth in portfolio and outreach of MFIs, intense competition and stricter regulations, the governance practices of MFIs needed to adapt quickly. Strong governance not only contributes to robust growth of the institution but also avoids the possibility of mission drift. There is a need for prudent corporate governance structure to prevent MFIs from committing the same mistakes they made earlier, which led to a crisis-like situation in the Indian microfinance industry in 2010.

In the light of this context, SIDBI’s PSIG programme commissioned MicroSave to assess the “as-is” status of key corporate governance models followed by Indian MFIs, boards’ roles and responsibilities, executive management and oversight, level of involvement in policy development, corporate oversight and strategic planning process and so on.

The study was accomplished and the report was launched in a conference-cum-workshop on June 3, 2015. The conference was attended by industry stakeholders comprising microfinance practitioners, donors and investors, lenders, and industry experts. The conference presentation captures the summary of the report titled, “Governance Practices among MFIs in India” and provides a snapshot of the governance models adopted by MFIs in India.

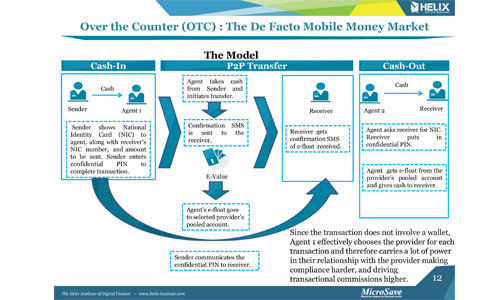

Pakistan is easily one of the top five leading digital finance markets in the world; yet also certainly one of the least understood. Anyone striving to learn about it must first understand how the Over-the-Counter (OTC) methodology adopted in Pakistan works, as it operates uniquely compared to other markets, especially those where it is unregulated. Its dominance in Pakistan has greatly influenced how the market has developed, and the recently released Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Pakistan 2014 report provides great insight into how the methodology had led to a fractured market and powerful agents.

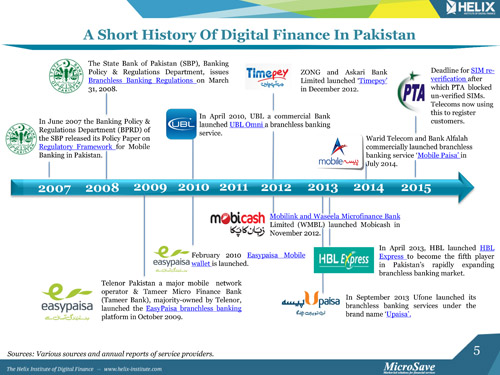

A Short History of DFS in Pakistan

The telecommunications market in Pakistan in 2009 was quite competitive with five providers each holding significant market shares. This was when Telenor Pakistan (in partnership with Tameer Microfinance Bank) launched the first digital financial service, Easypaisa. However, they did not want to limit the potential user base to the 22% of mobile phone subscribers that used Telenor SIM cards so they led with a methodology called Over-the-Counter (OTC) in which transactions are executed by the agent at the outlet, as opposed to over a mobile wallet platform by the customer. Therefore, agents are able to conduct transactions for everyone as opposed to being limited to those carrying the specific SIM card of the provider.

OTC Makes it Easy to Get Customers but Very Hard to Keep Them

The OTC method meant that Easypaisa did not have to invest in convincing individuals to register for a mobile wallet and instead could just register agents and promote the use of the service at agent locations. While this surely helped catalyse growth rates in transactions, it also left the door open for other providers to follow suit. In an OTC market, neither the amount of SIM cards a provider has in the market, nor the amount of customers they have registered for digital financial services yield significant competitive advantages. Therefore, while the methodology allows providers with smaller market shares in the voice/banking business to potentially scale transactions quickly, it also means that being the first mover in the market is not necessarily an advantage.

The first mover (if they do a good job) actually lowers the barriers to entry for its competitors by conducting initial agent training and also funding the initial marketing campaigns that make the population aware of what the service offers. Therefore subsequent movers in the market have a much easier task as they can simply register already trained agents to provide services to already aware customers with relatively less investment. They just have to ensure that the service they offer is similar to that already on offer so that it is easily understood.

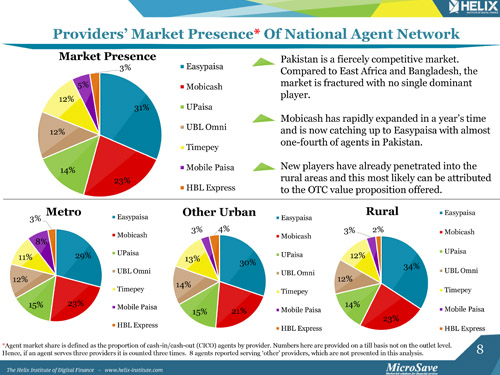

The Fractured & Volatile Market

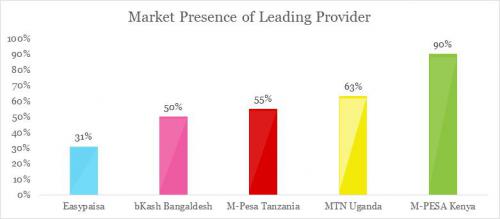

The aforementioned factors have lead the Pakistani market to become more fractured and volatile compared to the other leading digital finance markets studied by The Helix Institute—Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya and Bangladesh. The leading brand in Pakistan, Easypaisa has the lowest overall market presence compared to the market leaders in the other countries, meaning there a smaller magnitude of market dominance from a single provider.

Pakistan also has the most competitors in the market, with six providers that have five percent or greater market presence, whereas Bangladesh only had four when surveyed in 2014 and the East African markets all had three or less. This means that not only do market leaders have the smallest leads on their competitors in Pakistan, but they also have the most competitors to compete against.

Further, there is incredible volatility in the market share each provider controls in terms of transaction volumes and values, and in their individual market presence in terms of how many active agents they have offering their services in the market. Mobicash and Upaisa have managed to grow at incredibly robust rates, displacing providers that launched years before them because again the easy to adapt OTC method actually enables big telecoms to quickly convert their GSM retailers into digital finance agents..

Agents Decide which Service Provider a Customer Uses

The OTC methodology switches the location of the battlegrounds for market share from the customer (as seen in mobile wallet-based markets) to the agent. Again, this is because the service a customer uses is not determined by the SIM in their phone or the card in their pocket, but by which service provider the agent chooses to use to execute the transaction. The agent then has the power to tell a customer to use one provider over another for reasons like the customer’s preferred service provider is not working or is inferior for some reason. Therefore, instead of employing product innovation to win customers, Pakistan is subject to commission wars to win agents. Providers constantly have to manoeuvre each other to provide agents with enough commissions relative to competitors to have them consistently use their service as opposed to their competitors.

The Future

Over the years, as the competition has intensified, providers report investing higher percentages of revenues back into agent commissions, steadily decreasing their own margins and leaving them in the same position in the next month when they have to fight for an agent’s loyalty once again. It is the story of fractured markets and of powerful agents. However, in the beginning of 2015, the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) asked all telecom providers to biometrically register all their SIM cards, and providers have been using this as an opportunity to also register customers for mobile-based wallets. While several million customers have been registered for wallets since the beginning of the year, the real challenge will be for providers to design products to deliver over this channel that will really interest customers.

A customer walks into a shop and tells the retailer … “I would like to send money to [another city] …”. The discussion continues until, after verifying the customers original CNIC (Computerized National Identity Card) to meet KYC/AML requirements, the shopkeeper transfers money from his account. Once this is done, and the customer has confirmed that the recipient has indeed receive the money, the customer hands him both the money transferred and the commission payable. An over the counter (OTC) mobile money transaction has been completed, without the customer touching his own mobile phone. For a great overview of how OTC works in Pakistan see slide 12 of the excellent agent network survey of Pakistan from The Helix Institute of Digital Finance.

“7 percent of the respondents use mobile money, only 0.4 percent have registered their own accounts. This indicates the majority of mobile money users access the service through an agent, through family or through a friend (over the counter).” – Intermedia Pakistan Wave Report-2014

1) Why it works for Customers?

In Pakistan, more than 10 million people are “settlers” (migrants from one rural/tehsil/city to other city/urban areas). The majority of settlers are “labourers”, characterized by low literacy and low income. In addition to these labourers, drivers, guards, cooks, servants and other low income earners have their families living outside the city. And their families need money/cash for their necessities. In Pakistan, the typical ratio of income earner to dependents is very low, so that 1 or 2 out of 5 or 6 earn money on daily/weekly/monthly basis. This results in a routine and ongoing process, in which the dependent receiver demands cash from the earning sender on regular/emergency/ad hoc basis.

In a recent report published by InterMedia. OTC use dominates the market. 94% of the respondents who use branchless banking services have not registered their own accounts, meaning that they prefer to conduct transactions through an agent’s account.

Five years ago money was sent via “Hawala” or “Hundi” channels or money orders from the Post Office. However, these channels took relatively long to complete the transaction – both for the process of sending and receiving cash, and the time for transmission in between. This weakness was the opportunity for Pakistan’s branchless banking industry, which rapidly scaled the “OTC” business for sending money around the country. Currently, in Pakistan around USD 200 million is transferred in 4.7million transactions each and every month – an average of $43 dollars per transaction. Such is the speed and reliability of the service that users are ready to pay extra (compared to the Hawala and postal office channels).

OTC provides the unbanked account customer opportunities to transfer money, pay utility bills and top-up their mobile phones at any agent location across the country. The State Bank of Pakistan’s Branchless Banking Quarterly report for October – December 2014 reports that the number of agents involved in branchless banking activity are 204,073 (up 9% from the previous quarter). However, the incidence of shared agents in Pakistan is around 66% (see 2014 ANA Survey for Pakistan) and active agents are estimated to be 80%.

Customers no longer go to bank branches to settle utility bills – the branches are often both far away and crowded, meaning that customers have to travel and then wait in long queues to make a simple payment. They prefer to just go to the nearest branchless banking agent to pay their utility bills.

2) Why it works for Agents?

In the beginning agents were unclear of the value proposition offered by branchless banking. Telcos had widespread agent networks and business alliances to sell air time across Pakistan. These agents compared their branchless banking commissions (0.5-0.7%) with their airtime commission (2.5%) and drew the obvious conclusion.

But this conclusion changed quickly when they observed the tremendous growth in OTC business. Meanwhile, those agents who had made their reputation in the micro-market of their community were able to generate significant customer footfall at their premises and to make good profits on their branchless banking business.

However, ultimately, the agent provides the same services across all branchless banking channels, but will push customers to conduct the transaction on the platform of the player offering the largest commission or other incentives. Currently the majority of branchless banking players (both MNOs and banks) have to offer substantial commission to get agents to push customers to use their channels, as with OTC transactions, agents essentially control the choice of channel used by the customer. These promotions have reach eye-watering heights – agents can double or even triple their commission by choosing one money transfer channel over another. In Pakistan the agent is king!

3) Why it works for Providers?

The majority of players in Pakistan believe that the OTC channel is viable and plays a vital role in the business case for the branchless banking model. To build customer numbers, transaction volume and market share every player is aggressively pushing the OTC money transfer business and using their marketing/promotion budgets for push strategies, resulting in more revenue even when profitability is, in many cases, limited by the expense of commissions and incentives offered to agents.

The late entrants are still far behind in building a strong OTC channel, and their profitability and business are at risk

Source: State Bank of Pakistan’s Branchless Banking Quarterly Newsletter for Oct – December 2014

In addition to the traditional uses of OTC, players are now concentrating on other products to offer their customers using the channel. These include IBFT Inter Bank Fund Transfer, merchant payments, disbursement of pensions and salaries, cash-in cash out, loan collections and disbursement for MFIs including Tameer Bank, TRDP (Thur Rural Deep Program), Khushali Bank etc. Branchless banking players in Pakistan now realise that the stronger, the more diversified and heavily used their channel is, the more return on investment … and that this necessarily requires them to shift users from making unregistered to registered transactions to create customer loyalty/“stickiness” and thus reduce the endless churn associated with (agent-driven) unregistered OTC transactions.

From the table below on annual activity rates, from the State Bank of Pakistan’s Branchless Banking Quarterly Newsletter for October – December 2014, we can see that still OTC dominates, comprising 86% of the market and 88% of the value of transactions, and that the majority of these are (P2P) fund transfers and bill payments. By contrast, m-wallet users’ activity is (perhaps unsurprisingly) dominated by cash deposit/withdrawals and top-ups.

|

Customer’ Transactions Analysis – OTC Vs M-Wallets |

|||||||||

| Quarter Oct – Dec 2014 |

OTC |

M-Wallets |

|||||||

|

Million Trx |

% of Total Trx |

$ Million |

Avg. Trx ($) |

Million Trx |

% of Total Trx |

$ Million |

Avg. Trx ($) |

||

| Fund Transfers |

28 |

48% |

1,223 |

44 |

1 |

6% |

22 |

37 |

|

| Bulk Payments |

3 |

4% |

108 |

43 |

1 |

13% |

57 |

48 |

|

| Cash Deposit & Withdrawal |

2 |

4% |

89 |

42 |

4 |

39% |

135 |

36 |

|

| Bill Payments |

23 |

41% |

319 |

14 |

1 |

5% |

11 |

21 |

|

| Top-Ups |

1 |

1% |

1 |

2 |

4 |

37% |

2 |

1 |

|

| Loan Disbursement / Repayment |

1 |

1% |

22 |

31 |

0 |

0% |

0 |

27 |

|

| Cash Collection / Payment Services |

0 |

0% |

13 |

89 |

0 |

0% |

0 |

45 |

|

| IBFT |

0 |

0% |

10 |

116 |

0 |

0% |

24 |

593 |

|

| Others |

0 |

0% |

8 |

75 |

0 |

0% |

0 |

23 |

|

| Total |

58 |

100% |

1,793 |

31 |

10 |

100% |

251 |

26 |

|

| %age of Total |

86% |

88% |

14% |

12% |

|||||

According to SBP’s newsletter (Oct-Dec 2014), the major development during the quarter was the growth in the number of m-wallet transactions – by 22% to 9.7 million compared to 7.9 million during the previous (July-Sept 2014) quarter. The jump in the number of transactions was also reflected in the 26% increase in the value to Rs.25.5 billion ($250 million) compared Rs.20.1 billion ($200 million) in the previous quarter.

The key factor underlying this growth was the increasing trend in mobile to-ups (36%) and for cash deposited into (19%) and withdrawn from (20%) m-wallets. But encouragingly, there was a remarkable increase in m-wallet to m-wallet transfers from just 43,848 transactions of Rs.46 million ($0.45 million) in the July-Sept quarter to 185,023 transactions of Rs.447 million ($4.4 million) during the Oct-Dec 2014 quarter.

|

Mobile Wallet Transactions Trend – Quarter to Quarter 2014 |

|||||||||

| Types of Transactions |

OCT – DEC 2014 |

JUL – SEP 2014 |

|||||||

|

Tranx Count |

% of Total Tranx |

Throughput (Million PKR) |

Throughput (Million $) |

Tranx Count |

% of Total Tranx |

Throughput (Million PKR) |

Throughput (Million $) |

||

| MW to MW Transfers |

185,023 |

2% |

447 |

4.43 |

43,848 |

1% |

47 |

0.46 |

|

| Other FT (In and Out) from MW |

393,475 |

4% |

1,730 |

17.13 |

376,955 |

5% |

1,661 |

16.44 |

|

| G2P / Bulk Payments |

1,291,324 |

13% |

5,845 |

57.87 |

1,285,634 |

16% |

5,803 |

57.46 |

|

| Cash Deposited in MW |

1,856,930 |

19% |

5,921 |

58.63 |

1,484,340 |

19% |

4,755 |

47.08 |

|

| Cash Withdraw from MW |

1,918,634 |

20% |

7,807 |

77.30 |

1,403,289 |

18% |

6,257 |

61.95 |

|

| Utility Bill Payments |

492,183 |

5% |

1,081 |

10.70 |

508,704 |

6% |

1,413 |

13.99 |

|

| Mobile Top-Ups |

3,524,482 |

36% |

183 |

1.81 |

2,808,896 |

35% |

151 |

1.50 |

|

| Loan Repayments |

202 |

0% |

1 |

0.01 |

118 |

0% |

0 |

0.00 |

|

| IBFT |

41,282 |

0% |

2,471 |

24.46 |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0.00 |

|

| Others (Donations/Payments/etc) |

20,966 |

0% |

49 |

0.49 |

29,422 |

0% |

102 |

1.01 |

|

|

TOTAL |

9,724,501 |

100% |

25,535 |

252.82 |

7,941,206 |

100% |

20,189 |

199.90 |

|

In the second part of this blog, “Over the Counter (OTC) in Pakistan: The Challenges and the Way Forward” we examine the challenges the success of OTC has thrown up, the response from the providers and the prospects for the future of branchless banking in Pakistan.

The Government of India is undertaking the most ambitious financial inclusion drive in history. The effort has two key elements: the financial inclusion plan called Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) and direct benefit transfer (DBT) payments from the government into beneficiaries’ bank accounts. The success of these efforts hinges on one factor above all: the quality of the last-mile banking agent (Bank Mitr – “friend of the bank”) networks that will disburse DBT payments and enable customers to access their bank accounts.

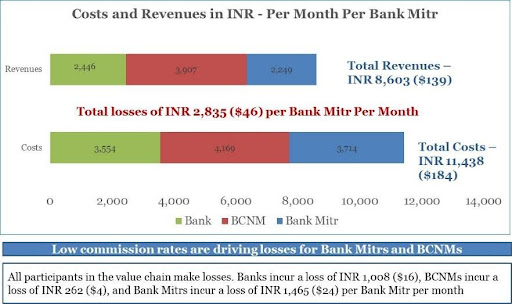

Bank Mitr networks in India have been weak, with a recent study showing an annual attrition rate of 25-35%. A recent MicroSave analysis found that nearly one-third of Bank Mitrs are unavailable at their stated locations. Many have stopped offering services because commission rates for processing government benefit and subsidy payments are too low. Business correspondent network managers (BCNMs) also make losses, but have invested heavily in anticipation of the emergence of a viable model and so are loathe to pull out (but are probably being forced to cut corners on training / quality control). Banks also make losses, but absorb them as this is a government programme in which they (particularly public sector banks) must participate.

Bank Mitr networks in India have been weak, with a recent study showing an annual attrition rate of 25-35%. A recent MicroSave analysis found that nearly one-third of Bank Mitrs are unavailable at their stated locations. Many have stopped offering services because commission rates for processing government benefit and subsidy payments are too low. Business correspondent network managers (BCNMs) also make losses, but have invested heavily in anticipation of the emergence of a viable model and so are loathe to pull out (but are probably being forced to cut corners on training / quality control). Banks also make losses, but absorb them as this is a government programme in which they (particularly public sector banks) must participate.

The Ministry of Finance’s Department of Expenditure released an Office Memorandum (OM) on 16thJanuary 2015 that fixes commissions for banks distributing DBT payments for rural areas at 1% (and even less for urban areas). For Bank Mitrs, this means that, currently, processing DBT payments result in a loss.

With such low commissions, there is no business case for Bank Mitrs to distribute these government subsidy payments. Therefore, the low commissions could potentially derail the entire financial inclusion effort. Indeed, the Task Force on Aadhaar-Enabled Unified Payment Infrastructure estimated in its 2012 report that a 3.14% DBT commission would be needed to ensure a robust rollout of Bank Mitrs.

A new MicroSave costing exercise found that the cost to banks of processing transactions through the agent network is at least 2.63% of each transaction – and (since this is an average) considerably more in remote rural areas.

Banks have been losing money when handling DBT pay-outs. Based on our on-the-ground research and analysis of costing data from the Bank Mitrs and Business Correspondent Network Managers who manage the Bank Mitrs, we concluded that a 3% DBT commission would be needed to ensure a viable distribution channel.

While the cost to the government of paying DBT commissions may seem high, it should be evaluated in light of the significant savings that the government will realise through reduced administrative costs and reduced payment leakages to unintended recipients. A 2011 McKinsey & Company analysis of India’s government payment system, estimated it to be Rs.100,000 ($22.4 billion) annually.

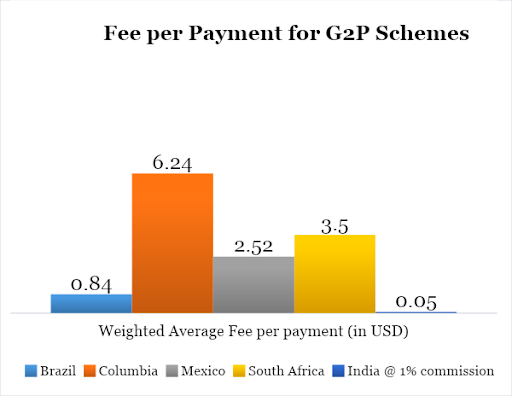

The 1% commission rate is also remarkably low in the international context. We re- analysed data from CGAP’s “Social Cash Transfers and Financial Inclusion: Evidence from Four Countries,” and found that India’s weighted average fee per transaction (basis calculations using MNREGA income support, public distribution system food subsidy and LPG subsidy payments) was just 6% of the next lowest country (Brazil). Of course, this is in part driven by the low value DBTs made in India, but the costs of conducting the transactions, whether large or small, are largely the same.

Another point to consider is that the government need not pay 3% commission to Bank Mitrs in perpetuity. According to MicroSave estimates, as the network of Bank Mitrs expands and more DBT programs flow through these accounts, the cost of processing DBT payments through an agent could potentially fall to as low as 1.4%.

In Policy Brief #12, we recommend that the government set an adequate rural DBT commission rate of at least 3% for the first few years of PMJDY. This would help ensure quality services and build a Bank Mitr network that is more sustainable. Over time, as payment volumes increase and the cost of processing DBT payments decreases, market forces and the bargaining capacity of banks will lead to lower commissions

(The blog was first published on CGAP)

In the first part of this blog, “Over the Counter (OTC) in Pakistan: Why It Works”, we examined the drivers behind the roaring success of OTC-based services in the country. This blog examines the challenges this success has bought, how the providers are responding and the prospects for the future of branchless banking in Pakistan.

4) What are the challenges for Providers?

5) How are providers responding to these challenges?

In the current environment all branchless banking players have failed to respond effectively to these challenges. While the substantial expansion of account opening, an enlarged agent base and the introduction of the biometric verification system (BVS) is laying the foundation for a critical mass of mobile wallets, the industry is unable to convert these acquired wallets into active users.

Different market players are tackling cash management issues through different methods. Agents with high liquidity are being selected and used to provide liquidity support to smaller agents in the same locality and effectively being used as master/liquidity support agents. For MNOs this function is performed by their respective franchises, which are even extended credit on weekends to support agents tagged within their defined boundaries.

6) What is the future for OTC and branchless banking in Pakistan?

Future of OTC in Pakistan looks bright, especially in the money transfer business, which is still growing.

| Money Transfer Tranx and Volume | Million Tranx | Per Quarter (Million $) | Per Month (Million $) |

| 2nd Qtr 2014 | 26 | 1,068 | 356 |

| 3rd Qtr 2014 | 27 | 1,161 | 387 |

| 4th Qtr 2014 | 28 | 1,222 | 407 |

Pakistan has a large and growing population base where the overwhelming majority (86%) of the adult population is unbanked. However, the growth of brick and mortar banking is limited by the high cost of conventional banking as well as lack of awareness, the complexity of documentation required and a host of other factors. Another important element is the role and size of Pakistan’s informal economy which employs a significant portion of the labour force. This segment is largely excluded from conventional banking channels because it cannot meet the extensive documentation required to open an account. Branchless banking can provide the platform that enables this segment of the society to make the first step towards becoming financially included, as it can offer convenience, easy access and reliability to this population. Taking those served by the current OTC offering to the next level to provide them access to savings, insurance and merchant payments will require very significant and concerted effort by branchless banking providers and the government. Some efforts are underway, but we should not underestimate the scale of the challenge.

Mr. Ashraf Mahmood Wathra, Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan, recently announced at the 8th International Mobile Commerce conference in Karachi Pakistan, “The National Financial Inclusion Strategy, recently developed by the State Bank of Pakistan in collaboration with the World Bank envisions that the uptake of m-wallet accounts will cross 50 million over the next five years”

In 2015, additional initiatives have been taken to increase the transactions/penetration on m-wallets, including:

While the initial indications of the results of these initiatives look positive, they are on a modest base. M-wallet to m-wallet transfers increased from 43,848 transactions (of Rs. 46 million [<$0.5 million]) in July-September 2014 to 185,023 transactions (of Rs. 447 million [$4.4 million]) during the October-December 2014 quarter. This represents an important four-fold increase in the number and nine-fold increase in the value of these transactions in one quarter – so an exciting step forward (see a detailed discussion of this in “Over the Counter (OTC) in Pakistan: Why It Works”

Nonetheless, agent-assisted OTC transactions are likely to remain dominant in the Pakistani market until all stakeholders support the unbanked population to open and use accounts by defining real use-cases and products to support them. Stakeholders will then need to increase marketing and communication to drive awareness of m-wallets, and their value of proposition. This must be backed by the provision of easy and convenient user interfaces to facilitate the conduct of m-wallet transactions, and the development of an eco-system across the country. Otherwise mobile wallet transactions will continue to work in different silos and will not achieve the SBP/World Bank’s goal and begin to convert Rs.2.73 trillion [$0.27 trillion] of physical cash into digital money.