The Government of India spends about USD 71 billion every year on various G2P welfare programmes on food, fertiliser, fuel (liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and kerosene), health, pensions, rural employment etc.

Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) in G2P programmes is a major reform initiative launched by the Government of India on 1st January, 2013. Its purpose is mainly to re-engineer the existing benefit-delivery processes and provide digital governance using modern Information and Communication Technology (ICT). In brief, DBT intends to achieve:

(i) Electronic transfer of benefits, minimising the number of levels involved in the flow;

(ii) Reduced delay in payments;

(iii) Accurate targeting of the beneficiary; and

(iv) Curbing pilferage and duplication.

The definition of DBT has also expanded over the years. Today, DBT not only encompasses direct transfer of cash benefits, but also in-kind benefit transfers, and transfers to the service providers/enablers who deliver benefits. Following is an illustration of the architecture of the DBT framework in India.

MicroSave through its Government and Social Impact (GSI) domain provides technical expertise to government ministries, departments, and other agencies. It delivers solutions for the successful implementation and management of multiple initiatives in G2P programme delivery, financial inclusion, and digital governance. During this DBT journey since 2014, several lessons were learnt. This blog highlights key findings on digital governance, G2P programme delivery, and financial inclusion.

Digital Governance Unique identity: India’s unique identity Aadhaar serves as the base for the majority of governance reforms. Linking of bank accounts with Aadhaar for DBT allows efficient tracking and monitoring of benefits transferred.

For example, as part of the end-to-end computerisation of Public Distribution System (PDS), the government uses Aadhaar to digitise and deduplicate the database, and for the distribution of rations using the Biometric Authentication Physical Uptake (BAPU) model. This helps to reduce the diversion of rations and ensures targeted delivery to the intended beneficiaries.

Database integration: Multiple servers host beneficiary data such as bank account, demographic, and other scheme-specific details, which is required for digitisation. These servers are controlled by multiple agencies.

For example, in the case of digitisation of the fertiliser subsidy programme in India, a common belief was that in the beneficiary databases of Aadhaar, soil health and land records are seamlessly integrated. It was in fact, not so, and this at one stage jeopardised the entire programme. The key lesson is to start with a simple scheme and gradually build a more complex multi-faceted system. However, a digitised, dynamic, and integrated database is an important element in the design of any successful Government to Person (G2P) programme. Such a database enables digital subsidy transfer, captures real-time changes, and allows targeting of benefits under one programme to one beneficiary.

Availability of common and transparent payment and settlement backbone: Effective use and management of public finances are essential for any government. An ideal system should provide real-time information on the availability and use of public funds across various G2P programmes, which will ensure transparency and accountability.

For example, the Government of India created PFMS to link the financial networks of the central government, state governments, banks, and other agencies. As of date, PFMS manages the payments of about 783 government schemes and interfaces with 80+ banks.

Use of technology: The use of technology has enabled a positive shift in the G2P ecosystem in the country. Earlier, grains, fertilisers, pensions, and LPG cylinders were distributed manually, without any Know Your Customer (KYC) process or authentication. Thanks to technology, we have now moved to a time when everything is digitised and distributed after proper authentication of the recipients. Technology can significantly increase the efficiency and effectiveness of welfare delivery programmes. But it is essential to move with, and be open to, the evolution of technology.

For example, in the fertiliser distribution system, the government has provided PoS devices to fertiliser retailers. The retailers use these devices to manage fertiliser stock and sell fertiliser to farmers using Aadhaar-based biometric authentication. However, the retailers have started facing issues such as small screen size of the PoS, shortened battery life, and lack of available maintenance and repair services. Moreover, these issues increase as the PoS machines age and become less effective. Based on the assessment of the fertiliser distribution pilot, we recommended the government to develop the PoS application as device agnostic. This would allow the retailers to use various devices at the front-end, such as laptops, desktops, tablets, and smartphones.

Presence of a robust grievance resolution mechanism (GRM):

It is necessary to have a grievance resolution system for every programme so that grievances are resolved promptly and efficiently. Acknowledgment of every registered complaint is important along with the provision of a turnaround time for its resolution. An effective grievance resolution mechanism is one through which the programme can be continuously improved while also bringing inputs into its design.

For example, in the Government of Rajasthan’s Bhamashah scheme, the state government has set up the Rajasthan Sampark Portal, which is an online registration system for grievances related to specific schemes and departments. Beneficiaries can easily go to e-mitras and register their grievances on this portal. However, our assessment of the scheme shows that less than 1% of the households use the portal for registering complaints. Hence, it becomes important to communicate to them, the benefits of using the GRM as well as the ease of using it.

G2P Programme Delivery

Communication: The digitisation of G2P programmes must be accompanied by high-quality communication campaigns that encourage beneficiaries to adopt new modes of subsidy delivery. The campaign should include:

(i) Communication on the enrolment process;

(ii) The amount of transfer;

(iii) The time of receiving the benefit; and

(iv) The process of receiving the benefit, as well as ‘what if’ questions, among others.

In the absence of an effective communication campaign, beneficiaries may often end up submitting documents more than once. For example, for cash transfer in PDS (in Chandigarh, Puducherry, and Dadra and Nagar Haveli), many beneficiaries submitted application forms more than once, as they weren’t sure if their previous application(s) had been accepted or rejected.

Pilot testing and independent assessment: It is important to conduct trial(s) and iterate the G2P programme extensively. In this context, pilot testing helps to understand not only the savings for the government but the convenience and cost implications for beneficiaries.

For example, we assessed cash transfers in PDS pilots in three Indian Union Territories (UTs) – Chandigarh, Puducherry, and Dadra and Nagar Haveli. Based on our assessment, the government of Dadra and Nagar Haveli decided to drop the pilot in rural areas but continued it in urban areas that are better equipped with banking and market infrastructure.

Incentive and commissions for stakeholders: A sustainable incentive and commission structure for players along the length of the entire value chain is essential. This helps motivate everyone in the delivery channel to implement these schemes.

For example, the success of the DBT in fertiliser programme in India is dependent on the support of fertiliser dealers, who sell subsidised fertiliser to the farmers. Prior to digitisation, these retailers used to earn a premium and make a profit by diverting bags of fertiliser. However, DBT has significantly reduced their financial viability. Currently, after paying for unloading costs, a retailer is able to make a profit of only USD 0.05 per bag of urea. Based on our assessment of DBT in Fertiliser, we informed the government that a significant number of fertiliser dealers have given up their licenses to sell fertilisers after the implementation of DBT. It was clear that, in the absence of a viable business model, the attrition of fertiliser retailers could negatively impact fertiliser distribution to farmers. In response, the government has now almost doubled the retailer commission from USD0.14 to USD o.27 per urea bag.

Exception management protocols: It is essential to have a blueprint for fallback options to handle failures and exceptions. Exception management protocols should be an integral part of the design of any G2P digitisation programme, rather than an ex-post facto procedure developed in haste to deal with glitches in implementation.

In the case of the food subsidy programme in India, an exception process kicks in if a beneficiary is unable to pick up his/her monthly quota of food grains due to biometric authentication failure or network connectivity issues. Exception management protocols include:

(i) A four-digit PIN sent to the registered mobile number – used to complete the transaction;

(ii) The Aadhaar number of more than one family member is mapped to the ration card ID, so that anyone can be authenticated; and

(iii) The transaction is processed manually under “no denial policy” and exceptions documented for offline check/audit.

Market marginalisation: International experience shows that wherever governments have intervened in the delivery of goods or services, they have marginalised markets. In the absence of markets, it is difficult to move to cash transfers right away. This has necessitated the intermediate move to digitise while retaining manual delivery.

For example, the Ministry of Food and Civil Supplies, Government of India, wanted to test the feasibility of cash transfer of food subsidy through pilot testing. Soon after they initiated the pilot in three Union Territories, the government had to stop it in rural areas of Dadra and Nagar Haveli due to low penetration into market infrastructure.

Amount sufficiency: When the government replaces in-kind benefits with cash benefits, it must ensure that cash is sufficient and regular. Our assessment of Indian cash transfer pilots in food subsidy shows that the subsidy amount transferred was unmatched to market prices; it was insufficient to purchase the same amount of grain as beneficiaries had received in-kind before the pilot.

For example, this was one of the problems in the case of cash transfer in food subsidy in the three Union Territories (Chandigarh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, and Puducherry). Similarly, we found that unlike regular LPG customers (who are usually from middle- and high-income segments), Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojna (PMUY) customers (who belong to the poorest segment) find it hard to afford an LPG refill with the modest subsidy amount.

Removal of redundant and avoidable intermediaries: An effective way to maximise the impact of government policies and interventions is to remove redundant and avoidable intermediaries from the system.

For example, earlier under the National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP), distribution of pension took place manually through post offices, making beneficiaries dependent on the postmen. Delayed or missed payments would take place when postmen did not visit the village. All these issues were resolved when the government digitised pension delivery and started to pay directly into the bank accounts of the eligible beneficiaries.

Financial Inclusion

Availability of last-mile payment infrastructure: In the absence of an extensive digital payment ecosystem, it is important to have an accessible last-mile network to withdraw cash for DBT programmes to succeed. Under the government’s Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) 316 million new bank accounts were opened, 126,000 Bank Mitras (BM) or bank agents were set up across the country, and 238 million RuPay cards were issued.

NPCI, an umbrella organisation for all retail payment systems in India, has also launched several new payment initiatives. These include Immediate Payment Services (IMPS), Unified Payment Interface (UPI), Bharat QR, RuPay card, Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS)and BHIM-Aadhaar. The objective is to reduce costs and improve the availability of interoperable last-mile digital payment options. (Some of the leanings that we have discussed in the ‘digital governance’ and ‘G2P programme delivery’ sections are also important for financial inclusion programmes.)

MicroSave was involved in India’s DBT journey from its commencement, providing research, advice, and technical assistance, giving us a ringside view of its programmes. We have also seen the success of several well-designed programmes and failures of a few poorly designed ones. It is extremely important that more attention and planning goes into programme design to ensure smooth implementation and reduce teething problems. India’s experience looks daunting, particularly given the huge numbers (of programmes as well as beneficiaries). However, it can provide important lessons and even a road-map for all governments that are preparing to implement digital government initiatives in G2P programmes and financial inclusion.

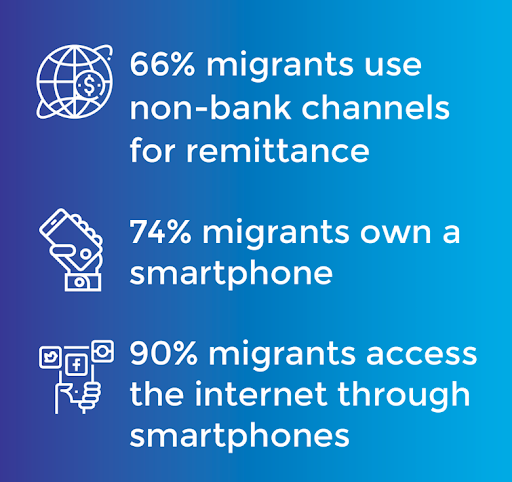

MyCash Online offers easy, secure, and convenient online financial services including domestic and international airtime top-ups, money transfers, airline and bus ticket bookings, bill payments, and e-commerce. MyCash Online offers its mobile and web application in six languages. The language options support the uptake and use of services for migrants from Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, and the Philippines. Since its inception in April, 2016, MyCash Online has served over 65,000 migrant workers and managed over 350,000 transactions valued at MYR 5.43 million (~USD 1.29 million). It has a network of 550 independent Mobile SalesPersons (MSPs)–MyCash agents.

MyCash Online offers easy, secure, and convenient online financial services including domestic and international airtime top-ups, money transfers, airline and bus ticket bookings, bill payments, and e-commerce. MyCash Online offers its mobile and web application in six languages. The language options support the uptake and use of services for migrants from Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, and the Philippines. Since its inception in April, 2016, MyCash Online has served over 65,000 migrant workers and managed over 350,000 transactions valued at MYR 5.43 million (~USD 1.29 million). It has a network of 550 independent Mobile SalesPersons (MSPs)–MyCash agents. For international remittances, MyCash Online has partnered with

For international remittances, MyCash Online has partnered with  [1] This document contains a few hyperlinks and readers are advised to read the document in conjunction with them.

[1] This document contains a few hyperlinks and readers are advised to read the document in conjunction with them.