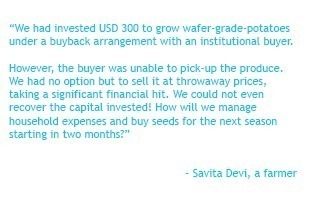

COVID-19 is likely to have a widespread, deep, and prolonged impact on every sector and segment. Farmers and cultivators in countries like India are rapidly starting to bear the brunt of the pandemic, even though restrictions and lockdowns have largely spared agriculture and allied sectors. The disruptions have affected the long value chains between cultivators and consumers. Retail prices have shot-up, wholesale prices continue to fall, while producers struggle to find buyers for their produce. In many areas, farmers lack access to adequate labor or equipment to harvest standing crops.

The impact on the next cycles of cropping is going to worsen as several factors start to play out. These include constrained logistics of input supplies to farmers, an anticipated shortfall in the availability of credit, subdued demand, unpredictable consumer behavior, and reduced buying power. Sadly, the worse may be yet to unfold!

What can players in the ecosystem do amid the gloom? Are there innovative and practical solutions to aid food security? Can we prevent massive wastage or losses and protect the livelihoods of smallholders?

Lessons from innovative ideas and approaches, and their rapid replication

India is known for its frugal and rapid innovations, termed colloquially as jugaad. Agtechs and other stakeholders in agri value chains are trying innovative approaches to reduce the fallout of COVID-19.

Savita Devi, an Indian Farmer

Lessons must be learned quickly, evaluated, and those that work should be scaled up. Governments, private players, investors, and start-ups will need to recognize solutions with high potential and invest in them to expand them rapidly. These are trying times like never before. Yet they also offer opportunities for unprecedented innovation, learning, and evolution of collaboration models.

Let us start at the consumer end. Household demand for staples and perishables is still high. We can say that this demand is reasonably inelastic, especially in urban areas and in the near-term. Closure of restaurants and workplaces has expanded demand somewhat, at the household level. Moreover new demand centers like community and government-sponsored kitchens have surfaced.

Entrepreneurs have developed simple demand aggregation solutions using Google Forms or over WhatsApp messaging. Once logistically feasible demand is generated, for example, a suitable truckload, entrepreneurs are completing fulfillment directly from farm gates. Agri-techs can do this either directly or in collaboration with active farmer cooperatives or producer organizations. Noteworthy examples include Praakritik, Sahyadri Farms, and Loop from Digital Green.

Based on anecdotal evidence, farmers who have been able to connect through these entrepreneurs are harvesting under-ripe fruits and vegetables. Earlier, market intermediaries would undertake the ripening process down the value chain. However, the current trend—and fear of coronavirus—makes consumers store fruits and vegetables for a couple of days before consuming them. This means that ripening is now happening on the shelves of consumers. This is beneficial for farmers as it reduces wastages. Moreover, the farmer has factored the increased time required to get the produce to the consumers with the prevailing lockdown in place.

Governments, such as in Maharashtra, are trying to devise innovative solutions. They have tied-up with leading farmer producer organizations to supply produce directly to households. However, logistics and fulfilment needs considerable strengthening. Getting to scale with such models is the challenge. Agri-techs that have robust farm-to-fork supply chains can provide important lessons.

Governments should collaborate with agri-techs that have the outreach and are capable of scaling up, rather than trying to create impromptu farm-to-fork supply chains.

Governments should collaborate with agri-techs that have the outreach and are capable of scaling up, rather than trying to create impromptu farm-to-fork supply chains.

As we move up the value chains, wholesalers and aggregators are facing a slowdown in demand from retailers and vendors. This is because of a combination of issues related to logistics and the partial closure of retail markets. Overall, wholesale prices are being driven down while the agriculture value chain from farm to fork faces many roadblocks. The friction in the supply chain has multiplied because of the lockdown. Reduced wholesale prices and increasing retail prices reflect the situation—not a happy one for either the farmer or the consumer.

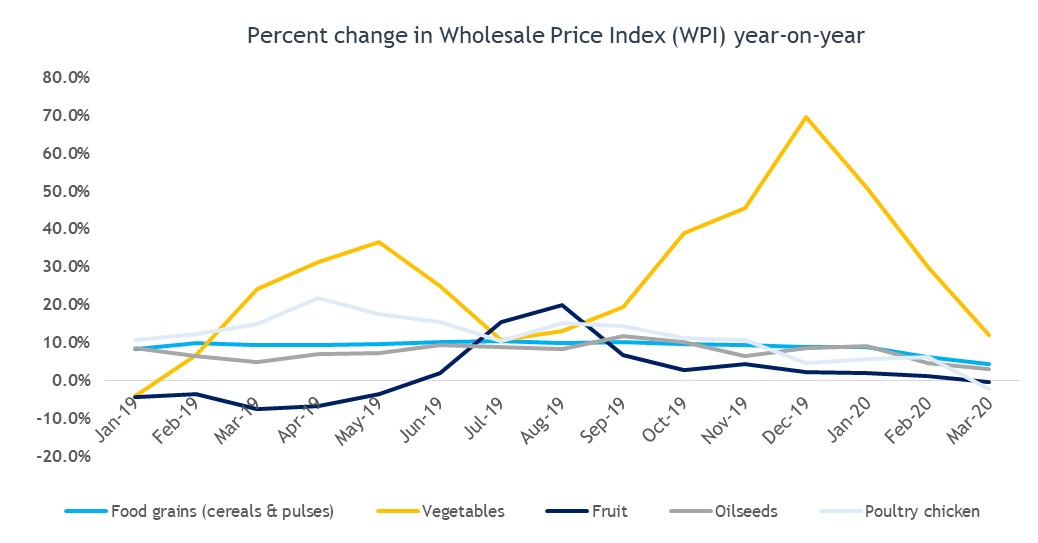

The year-on-year trend in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) for food grains, oilseeds, vegetables, fruit, and poultry exhibits a sharp downward trend. The disruption in retail supply chains of food grains and perishables is causing uncertainty in supplies and fluctuating prices. Meanwhile, panic buying and hoarding by high-income segments have started to create shortages for low-income segments.

Department of Co-operation, Marketing and Textiles, Maharashtra

Percentage in Wholeprice Index

Source: Government of India, MSC analysis

Governments and local bodies need to streamline operations of agri-markets even as they ensure safety. Some states have staggered the working hours in markets, with separate timings for buying fruit and vegetables and longer opening hours throughout the day. Wholesale agri markets are functioning from midnight to early morning in some districts in Uttar Pradesh. This discourages retail buyers from flocking to these markets in search of bargains. Other states are identifying new marketplaces to expand space for agri-transactions while reducing mass gatherings.

The critical role of self-help-groups

Low-income segments receive a significant part of their food supplies through the Public Distribution System (PDS) in India. Women self-help groups (SHGs) can play a vital role in strengthening the distribution of food grains. In the state of Bihar, SHG members undertake distribution of a select basket of food grains for the low-income households. This is managed through a World Bank-supported Food Security Fund (FSF) program.

In the state of Uttarakhand, SHGs and village organizations are actively involved in cleaning, sorting, packaging, and distribution of a basket of food grains. The state government has gone a step further to broaden the food basket to include local millets, which add nutritive value while catalyzing demand from local smallholders—thereby adding to their revenue streams.

SHGs and women cooperatives have proven their agility in this time of crisis. They are actively involved in producing new categories of products that are in demand. These include fabric masks, aprons, sanitizers, and soaps. The state rural livelihood missions (SRLMs) drive most of the SHG programs. State governments need to share lessons across different SRLMs and replicate innovations and best practices to achieve better outcomes.

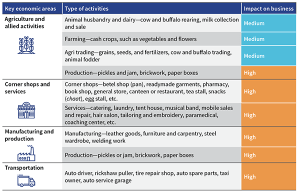

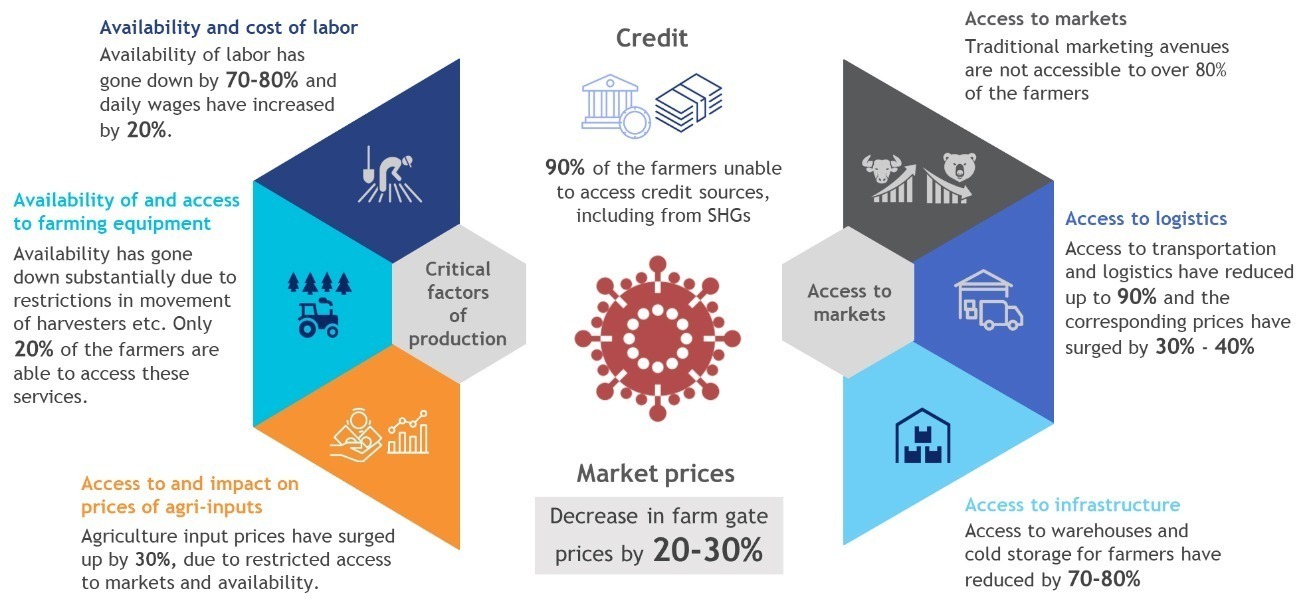

We now analyze how farmers, who are at the top of agri value-chains, are coping. MSC conducted a short research exercise with a few farmers, rural aggregators, and traders. The following exhibit summarizes the situation of the farmers and the distress they face.

Indian Market price and production illustrator

Farmers are suffering substantial economic losses due to disruptions in market access, logistics, and prevailing uncertainty.

They are uncertain and scared of threats and challenges related to their harvest-ready Rabi (winter) crops.

Harvested crops are either being sold at extremely low prices or are being stored in non-conducive conditions. Reports have emerged of farmers burning their standing crops, as the economics of harvesting them and transporting them to markets are not feasible.

Harvested crops are either being sold at extremely low prices or are being stored in non-conducive conditions. Reports have emerged of farmers burning their standing crops, as the economics of harvesting them and transporting them to markets are not feasible.

Burnt crops

Farmers are even more apprehensive of the upcoming Kharif (summer) cropping season. They are uncertain about the crops to plant. The situation of the market and the logistics at the time of harvest are unpredictable. The farmers are also concerned about the unavailability of farm inputs and credit.

Livestock farmers are equally distressed. For example, poultry prices have dropped more than 90% during the past two months. This is partly due to the unfounded belief that coronavirus can be transmitted through poultry.

Potential solutions for farmers

At this point, governments must undertake widespread communication with farmers and MSMEs in agri and allied sector value chains to allay fears, address misperceptions, and outline measures and interventions being taken.

MSC is planning to undertake a research project with farmers, traders, and other intermediaries. This will generate last-mile insights for policymakers and the sector at large, based on ground validated realities. Governments and policymakers should make informed decisions, determine appropriate responses, and calibrate actions to support smallholders and their families.

Under the leadership of JEEViKA and with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, farmer producer companies (FPCs), MSC, DeHaat (Agrevolution), and other partners have been working together to support smallholder farmers in Bihar. One of the interventions is to provide timely offtake and optimal value realization for the harvest-ready maize crops of farmers. DeHaat has an innovative model of continual physical and digital (phygital) engagement with farmers throughout the year by meeting their needs for inputs, advisory, marketing, and credit linkages.

Under the leadership of JEEViKA and with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, farmer producer companies (FPCs), MSC, DeHaat (Agrevolution), and other partners have been working together to support smallholder farmers in Bihar. One of the interventions is to provide timely offtake and optimal value realization for the harvest-ready maize crops of farmers. DeHaat has an innovative model of continual physical and digital (phygital) engagement with farmers throughout the year by meeting their needs for inputs, advisory, marketing, and credit linkages.

MSC is also exploring partnerships with innovators like GrainPro to provide low-cost hermetic storage facilities to farmers and FPCs. Farmers are unable to transport produce to warehouses or to markets. Temporary storage solutions at their farms or homes, therefore, can provide immense value. These will allow farmers to store grains for the short-term without infestation, degradation in quality or moisture levels, and thereby allow them to retain value.

A bag of grains

India has several innovative models similar to those of DeHaat and GrainPro. They include Kamatan, Crofarm, Ninjacart, WayCool, and many others. These institutions work across India on diverse agricultural or horticultural commodities while others like S4S Technologies, OurFood, and Ecozen provide smart and low-cost primary agri processing and storage solutions.

The country now also has a range of custom hiring centers (CHCs), some with Uber-like models. They can meet the shared needs of farm equipment economically and efficiently, particularly when availability is severely constrained.

The current situation provides an opportunity for governments and other stakeholders to collaborate and scale-up outreach that many of these MSME models find it difficult to achieve on their own. Farmer producer organizations and companies too can be important partner institutions in this multi-stakeholder approach, as the country prepares to ensure food security for all and to protect the livelihoods of farmers.

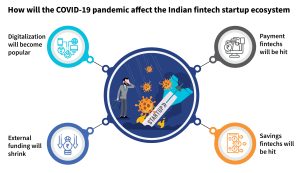

We are having to work out, in a very short amount of time, how we offer humanitarian relief and solutions to these problems, and how we do this from a distance. Most are turning to digital platforms such as DFS (digital financial services) as the answer. Many donor organizations are immediately looking to replicate reactions from elsewhere in the world by organizing massive G2P (government-to-person) payment programs to alleviate missing incomes and are looking to use DFS and mobile money to execute them.

We are having to work out, in a very short amount of time, how we offer humanitarian relief and solutions to these problems, and how we do this from a distance. Most are turning to digital platforms such as DFS (digital financial services) as the answer. Many donor organizations are immediately looking to replicate reactions from elsewhere in the world by organizing massive G2P (government-to-person) payment programs to alleviate missing incomes and are looking to use DFS and mobile money to execute them.