We can probably all agree that “sustainability” is a very tired noun. We use it to describe our wishful hopes for everything from human life on earth to improved supply chain management. And the reason we can’t quite give it up is because our need for a more equitable and enduring ecology, economy, and society remains as urgent as ever.

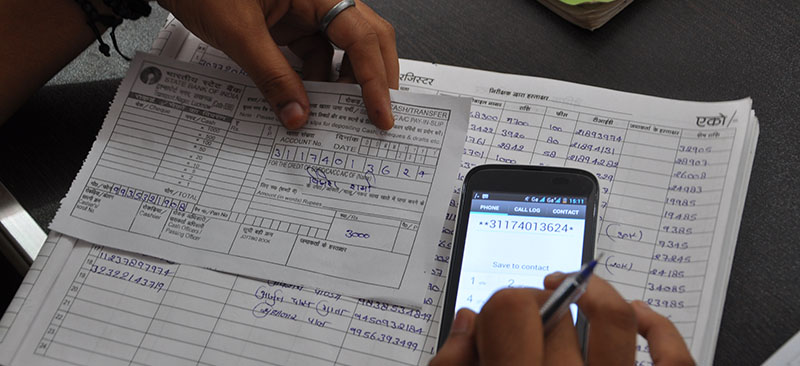

Mobile banking hasn’t really achieved sustainability yet. Everyone talks about it as an almost done deal. Nevertheless, cash still trumps all. Even for the success stories like M-PESA, MTN Mobile Money, Tigo Cash, and Airtel Money. Money seldom resides on any of these phones for very long before it’s cashed out. Small emergency funds and savings don’t last long either for customers whose lives are beset with periodic, expensive crises.

No, it’s not about remittances

Remittances would certainly seem to be the steady drip that turns into reliable revenue streams for mobile operators, bank partners, and other commercial interests involved. But the sending and receiving of a percentage of migrant wages are not the enduring “customer need” on which the truly sustainable business propositions depend.

For both the workers and their beneficiaries, these payments are an emotionally fraught mix of familial duty, leverage, guilt, resentment, and social expectations. They are isolated monthly payments that, over time, can become irregular and even cease altogether. Remittances are closer to dowries and mafia protection money than they are to a utility bill. Consumers also expect, even if they begrudge, the extra fees involved in these highly personal money transfers.

No surprise, while they are acknowledged as a “pain point” (see Removing the Pain from Using Cash: An M-banking Solution?) most people balk at spending one paise or shilling or pesewa more to pay their neutral, impersonal monthly costs—water, electricity, rent, phones—by phone. “Sustainable” in this instance may actually mean giving up on the short-term (and generally minimal) profits for the long-term benefits of full adoption and use of all the services mobile banking can offer. As far back as 2010, at the MMU conference delegates from TrueMoney-Thailand, Grameen Phone-Bangladesh and Telenor-Pakistan discussed why they started with bill payments.

Embedded fees for both remittances and bill payments seem to differ, depending on the country and social norms. In most cases, any payment involving an agent and cash-out also involves an extra charge. If simply cash-in, as is the case with most bill payments, fees are lower ($.07-.35) and often waived by banks, insurance, and credit agencies. In Pakistan, where bills traditionally never include an extra cost, Telenor started off with small fees and then stopped, bowing to competitive and customer pressures.

The idea that the neutral bills—water, electricity, rent, phone—are more integral to full financial inclusion than remittances is not new. MicroSave has been writing about the potential for E-/M-Banking via remittances and ways of effectively graduating customers since 2009. Two years ago, MasterCard published Bill Payment, A Demand-Based Path to Financial Inclusion and a CGAP blog Bank-Led or Mobile-Led Financial Inclusionalso makes a strong case for bill payments as a “pain point” that both banks and telecoms should promote in their mobile service offerings. And, of course, ultimately successful digital financial service solutions need a compelling product mix.

Even so, CGAP’s 2013 year-end roundup reports air-time top-up and P2P (person to person) payments still dwarf bill payments. (The most recent figures available are 18 months old, however, and South Asia’s bill-payment adoption appear to be a full third higher than East Africa. So more current—and more comprehensive—data, including from Bangladesh’s bKash and India’s Eko, would be useful before we reach any final conclusions).

Q—and several As

The real question would seem to be why more utilities, landlords, health clinics, credit and insurance agencies, in South Asia, East Africa, and elsewhere, do not actively encourage the throngs of cash-paying customers in their lobbies every month to pay by phone and save everyone a great deal of time and trouble.

And the real answers include:

- Too many m-pay promoters (banks, mobile operators, technology service providers) still think they can and should make money off convenience and speed—and then find themselves frustrated when m-payment profits fail to quickly materialise;

- Bill payers, even those most bedevilled by cash, generally resist change and/or new technology involving personal finance.

- Accounts Receivable also worries—with good reason—about “suspense accounts” (the e-limbo where questionable receipts, disbursements and discrepancies can reside indefinitely). M-PESA’s suspense accounts are infamous.

A dearth of reliable payment gateways for mobile cash in/out transactions in these markets also poses a significant deterrent. Most readers already know of payment gateways as the online systems that authorise and coordinate e-commerce and point-of-sale credit card-purchases. But as customer adoption rates for mobile payments are less than encouraging (see above), the banks and telcos who generally underwrite and support such gateways hesitate to invest – particularly in poor areas.

Utilities and other potential payees, large and small, also delay and debate m-payment agreements without a burgeoning and eager customer base, and without the relative security and improved efficiencies most payment gateways offers.

Online payment systems had even worse problems at the outset. Sooner or later, probably sooner, either a better technology will come along for the bankers and the largest, most ubiquitous payees. Or the cost of cash for all involved will simply become too onerous.

At that point, some magic number between 16-34 percent on all three sides of the transaction triangle—customers, payees, technical/financial enablers—cross Geoffrey Moore’s notorious chasm.

And then the real benefits begin to emerge. Payment and credit delinquency go down, account activity and customer loyalty go up, grievances usually diminish, and financial capability overall seems to improve. Worthy and possibly even sustainable New Year’s resolutions for 2014.