Blog

Workshop on Digital Transformation of Postal Operators: Massive outreach, opportunities and challenges

MSC (MicroSave Consulting), conducted a workshop on Digital Transformation of Postal Operators: Massive outreach, opportunities and challenges on the 24th of February, 2021.

This webinar was designed to promote thinking and action on the digital transformation of postal operators in order to leverage their outreach to deliver real financial inclusion. It focused on three aspects:

- The opportunities and competitive advantages enjoyed by postal operators;

- The challenges postal operators have faced or are likely to face as they digitize; and

- The various business models for postal operators.

The webinar had an eminent panel comprising CXOs of postal operators, the UPU and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to discuss these opportunities and challenges.

Getting behind the corona statistics: How a small shopkeeper took on the pandemic

Fifty-three-year-old Rezwan Kabir (name changed) is a former bus driver who had changed his profession after 20 years. It was 2007 and he felt he was growing too old to manage the grind of driving long distances. He opened a small daily provisions shop in a village market in central Bangladesh. The business gradually picked up and prospered—until COVID-19 struck Bangladesh.

Rezwan struggled with several challenges like supply issues, falling customer footfall, lockdowns, increased price of items, and the constant fear of infection. His income shrank and he had to withdraw most of his savings and put his plans to grow his business on hold indefinitely. Rezwan’s case is just one among the millions of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that faced unprecedented challenges during the pandemic. Many were closed permanently or forced to change their business, as losses piled up.

What surveys told us about the impact of the pandemic on MSMEs in Bangladesh

We examined two surveys conducted during the pandemic—MSC’s study of 90 MSMEs conducted in May, 2020 and International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) study of 500 MSMEs in June, 2020.[1] The IFC survey covered a wide range of MSME types, including farm based and non-farm enterprises , wholesalers, retailers etc. The MSC survey sample included a smaller proportion of manufacturing businesses and focused on shops and services.

The MSC study found that customer footfall had decreased for 94% of MSMEs in Bangladesh and sales had fallen for 85% of MSMEs. The pandemic had an impact on the supply chain too: 74% reported decreases in the volume, while 58% reported decreases in the value of supplies. 38% reported that suppliers had stopped offering credit and 28% revealed that they were offering less credit than before. The nationwide lockdown was in effect from 26th March, to 31st May, 2020. The survey was done when the lockdown was still in force and therefore captured the situation at its most severe.

The IFC dataset indicates that 83% of firms were making losses and 21% of them had closed temporarily, either by choice or by government mandate. 91% of the firms suffered from decreased cash flow, averaging around 52%. 67% of the firms were affected by shocks like a reduction in hours worked, reduction in demand, and unavailability of financial services. The survey was done in June, after the lockdown was lifted when economic activity had started to recover.[2]

These one-off surveys revealed the situation of the MSMEs at specific points in time. However, we needed to go behind the survey data to understand how the business owners survived the pandemic and know if have they started to recover, among other developments. To answer these questions, we can turn to other research methodologies like the Financial Diaries. The insights that we get from the data in the daily diaries can give us a more nuanced perspective than those derived from a one-off survey.

Arshad’s story: resourcefulness, resilience, and innovation

For the past five years, the Hrishipara Daily Financial Diaries project[3] has used the diary-based research to track 60 low-income households in Hrishipara, a village on the outskirts of a market town in central Bangladesh. In mid-2020, the project added to the sample five corner shops, which are stores for daily provisions. Here, we discuss the case of one such corner shop to understand its situation during the peak of the pandemic and assess if it has managed to recover. The store is owned by Arshad (name changed), who, along with four other corner shop owners, has been volunteering as a “diarist” since the third week of July, 2020.

He told us that his gross income started to decrease when the lockdown was imposed in late March. It reduced to an average of BDT 60,000-70,000 (USD 709-828) a week. This continued for two months and from June onward, Arshad’s gross income slowly started to climb back up but did not return to pre-COVID levels. During the peak of the pandemic between March to June, 2020, he would open his shop early in the morning when mobility was less strictly regulated by the authorities. Customers could come to his shop to buy their daily needs in these early hours and the arrangement worked for both parties.

He told us that his gross income started to decrease when the lockdown was imposed in late March. It reduced to an average of BDT 60,000-70,000 (USD 709-828) a week. This continued for two months and from June onward, Arshad’s gross income slowly started to climb back up but did not return to pre-COVID levels. During the peak of the pandemic between March to June, 2020, he would open his shop early in the morning when mobility was less strictly regulated by the authorities. Customers could come to his shop to buy their daily needs in these early hours and the arrangement worked for both parties.

In our first interview with him, Arshad told us he sells grocery items, cosmetics, and airtime from a shop that he owns and has been running for nine years. His shop is comparatively larger than other shops in his area and is situated in a prominent business location. Arshad estimated his weekly average gross income, that is, sales revenue before COVID-19 at BDT 210,000 (USD 2,483)[4].

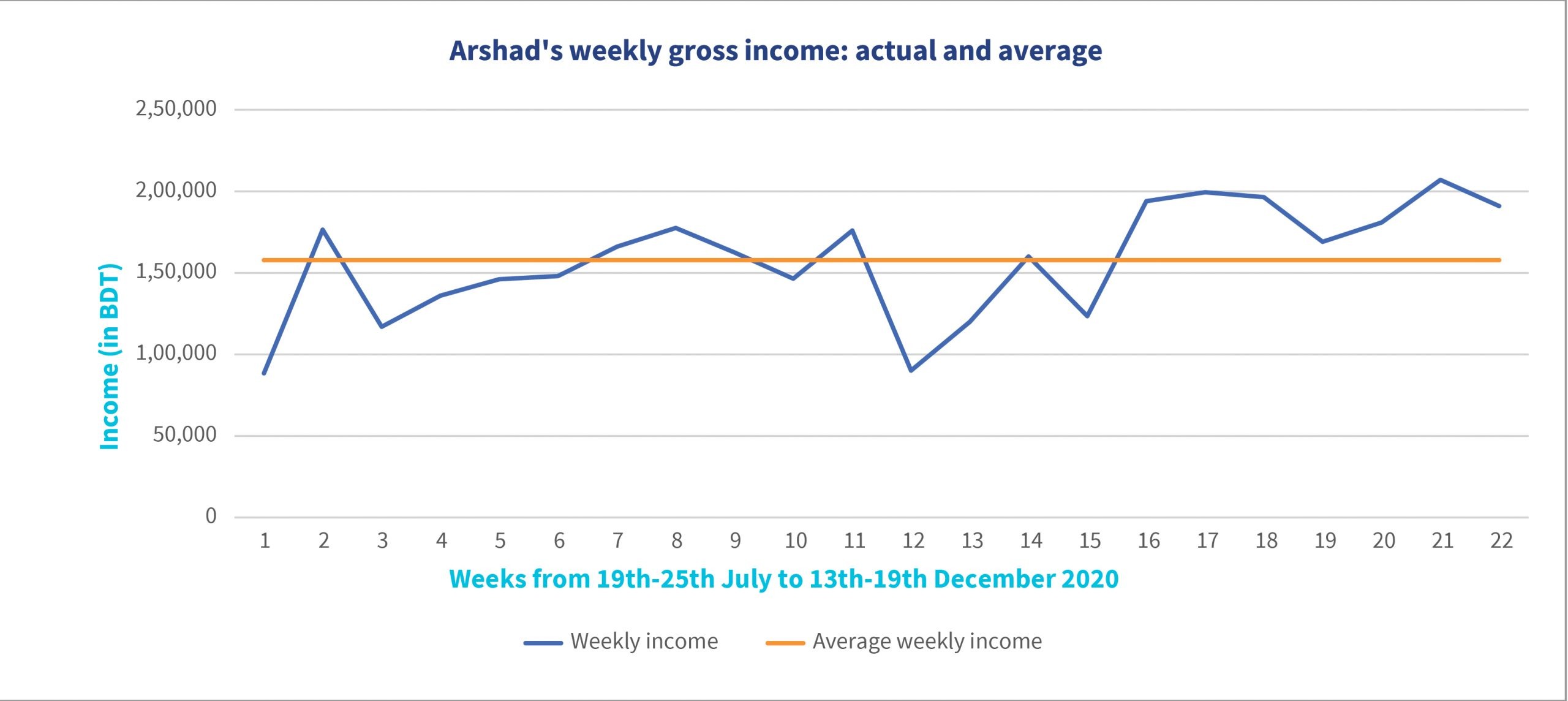

In Graph 1, we see that the weekly gross income in the first week of data collection was BDT 88,400 (USD 1,045) and the highest income was in the second week of December at BDT 207,000 (USD 2,447). The average weekly gross income throughout the period of data collection was BDT 157,805 (USD 1,866), which was still just 75% of the reported average weekly gross income in the time before COVID-19. The data suggests that sales are slowly getting back on track and the recovery process has started.

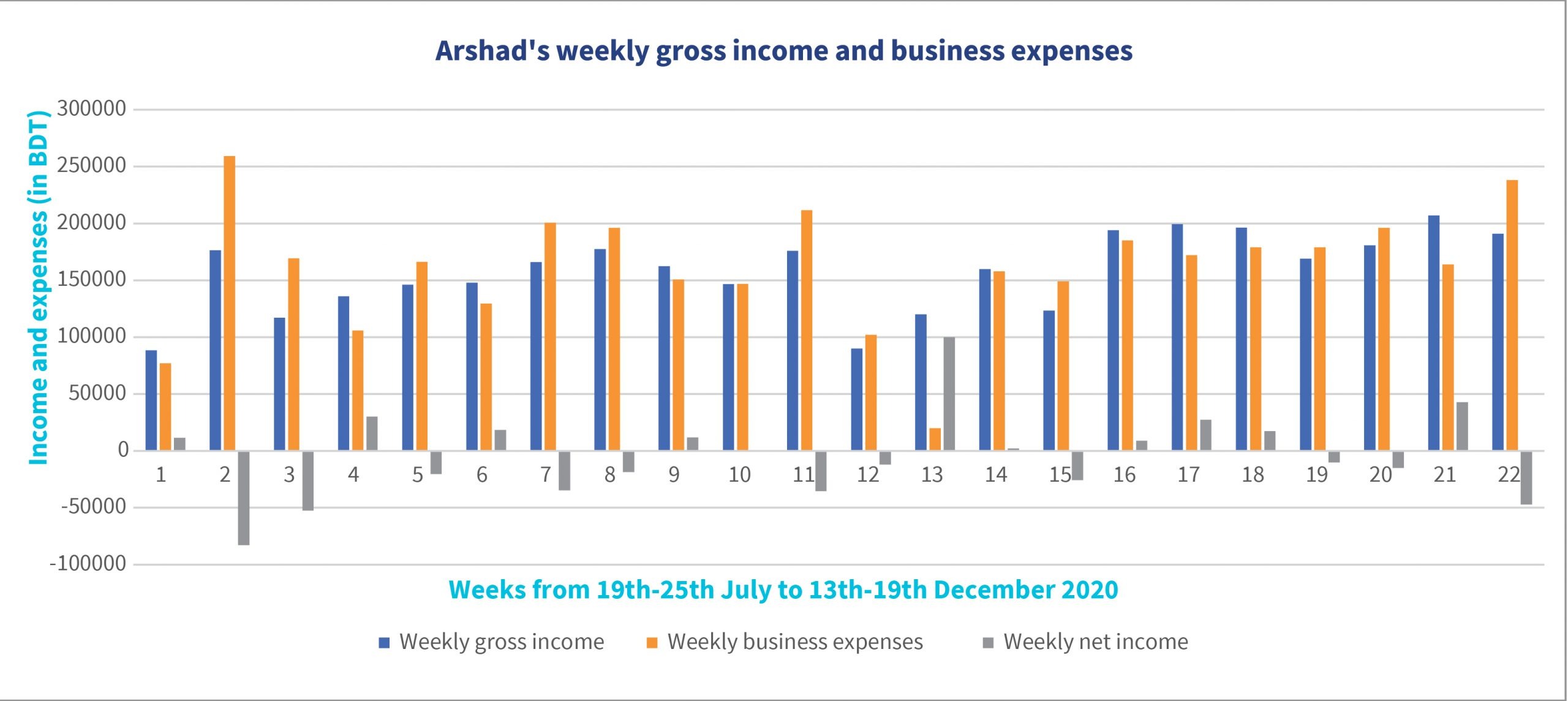

But what do the diaries say? Graph 2 depicts his weekly income, business expenses, and net income. Surprisingly, in more than half of the weeks (12 out of 22 weeks) during data collection, the net income of the week was negative—that is, the business expenses exceeded sales.

However, has he been making a profit? Arshad reported that before COVID-19, his weekly net income was in the range of BDT 14,000-15,000 (USD 165-177). After COVID-19 struck Bangladesh, in the first three months (March to June 2020) he told us that his weekly net income shrank to the range of BDT 6,000-7000 (USD 71-83).

Arshad was fortunate that his household had several regular sources of income, unaffected by the pandemic. This reemphasizes the importance of regular guaranteed income in situations like COVID-19—be it through a secure job or direct cash transfer. Fortunately, both the Government of Bangladesh and BRAC, the largest NGO in Bangladesh, ran cash transfer programs for the poor in the country and these programs helped millions of households to survive the pandemic.

How did he manage his household expenses in these tough times? Like many low-income households, Arshad has more than one stream of income. His wife is a government high school teacher, and her income takes care of some of the family expenses. Arshad’s household is part of a joint family—he lives with his elder brother’s family. One of his nephews works in Singapore and the remittances he sends helped the household during the peak time of COVID-19 and even now.

The pandemic has not changed the way Arshad runs his business. Operating the business in the early morning hours was a temporary coping strategy and Arshad discontinued this once the lockdown was eased. He chose not to digitize his business operations. His customers mostly pay him in cash, and most people in the locality do not have the means to buy digitally.

Among the 60 diarists of the Hrishipara Diaries project, none has a debit card, credit card, or other means to make digital payments. Though some use mobile money services (MFS), they do not use it to purchase goods at shops. In his dealings with suppliers, Arshad rarely uses DFS for payment because the suppliers, who must pay fees to withdraw the payments see it as an expensive option.

So, what do we learn?

- Arshad’s case highlights how bookkeeping and business training could help micro-businesses run more strategically. Not tracking income and expenditure carefully proves to be costly. Digital platforms to train micro-enterprises might help, but need to be complemented by capacity-building and by the adoption of digital systems by the low-income households that constitute Arshad’s customer base.

- A source of regular fixed income, in any form, is immensely important for a household’s financial health, especially in a time of crisis like COVID-19. Direct benefit transfers to the MSMEs (both formal and informal) by the government can help them maintain the financial health of their businesses.

- A continuous flow of nuanced data is needed to inform policy. In this regard, the Financial Diaries approach can be critical to the path toward recovery.

[1] The IFC survey sample was a mix of micro (65%), small (27%) and medium (8%) enterprises. A sample frame was prepared by collating lists of MSMEs from various sources and then sample was drawn using simple random sampling.

[2] See for example, the data on the Hrishipara Diary Project’s coronavirus page at https://sites.google.com/site/hrishiparadailydiaries/home/corona-virus

[3] The project is being funded by L-IFT since 1st June 2019

[4] 1 USD is equivalent to 85 BDT.

The COVID-19 paradox: What made a small corner shop in Uganda, which was allowed to operate during the pandemic, close down?

On one evening in mid-September, 2020, John Katembo (name changed) was visibly upset as he downed the shutters of Bushera Soft Drinks, his five-year-old enterprise, probably for the last time. He had sold the shop to a local businessperson for cash. John, age 26, lives in the Nakivale refugee camp in Uganda with his wife and son. John had to move to Uganda from his homeland in DRC owing to political unrest. Once in the refugee camp, his sole source of income was the regular cash benefit he received from the World Food Programme (WFP).

Understandably, this was far from enough and John had to quickly find a job as a data entry operator. His bachelor’s degree helped in the process. Always enterprising in nature, John was also on the lookout to start a business in the new country once his economic situation stabilized a little—and so Bushera Soft Drinks was born.

Throughout the duration when the Corner Shop Diaries program tracked John’s financial transactions, the shop helped John earn an average weekly amount of UGX 141,560 (USD 38). When COVID-19 struck Uganda in March, 2020, the government shut down almost all services. John’s business was among the few that were permitted to continue operating.

In the first weeks of the pandemic, John earned generous profits and his business boomed due to the high market prices of most products he sold—and the prices continued to increase with time. Yet at the end of September, 2020, he had to close down his business for good. What happened in between? What pushed John to close down the business that he built with his blood and sweat in a completely new country? Before we explain this paradox, let us first try to understand his financial life through data from the diaries.

A complex financial life susceptible to a crisis like COVID-19

At first glance, John’s income looks erratic (Image 1). This is a common phenomenon found in most financial diary studies across the globe. However, we can spot a trend if we classify the income by source. As evident from images 3 and 4, John’s income from sources besides the soft-drinks business remain mostly consistent over time.

Image 1

Image 2

Image 3

Image 4

We have analyzed the data from 2020 (Image 5) separately to understand if COVID-19 added more volatility to the income scenario. In the data from 2019, out of 19 weeks, we observed spikes in the income of six weeks and dips in the income of six weeks. This means that out of 19 weeks, six were spikes, six were dips, and only seven were “normal” or roughly the average. So, “normal” is the exception rather than the norm

Image 5

In the data from 2020, out of 43 weeks, we observed 14 spikes and 10 dips, with a lower proportion of dips (23%) in 2020 compared to 2019 (32%). So, we cannot say that the shop suffered a loss in income during the lockdown and more broadly through the pandemic.

Now let us look at John’s business expenses. In an ideal situation, as the business is well established, the expenses should have been mostly stable. However, the data on expenses for the soft-drinks business shows a decreasing trend overall. As the pandemic progresses in 2020, for the first time (Image 6), we see consecutive weeks (weeks 31-34 and 40-44) without any business expenses. However, toward the end, we see a few weeks when business expenses, related mostly to the purchase of raw material, were comparatively high. Seeking to understand the reason behind this, we learned that the government implemented curfews and closed all borders to prevent the import of the disease. Hence, the imports of commodities were also stopped. This explains the consecutive weeks without any business expenses. Throughout these weeks, during and just after the lockdowns, John could not restock his shop. This led to limited supply and subsequently, a shortage of commodities in the market. Thus, some monopolists started hoarding commodities for future use.

Image 6

This caused high demand, which led to high market prices. John eventually ran out of stock for his shop.

In this kind of situation, those with a savings reserve generally manage to survive, as money can buy stock even at higher prices. However, John had limited savings. He saves money in two ways—through a SACCO (Savings And Credit Cooperative Society), MOBAN (Moral Brotherhood and Neighborhood), and loans to others.

- In the data for 19 weeks in 2019, John’s total savings were 56% of his total income in 2019. Of his total savings in 2019, 65% was saved in the SACCO and 35% through lending.

- In the data for 43 weeks in 2020, John’s savings were just 22% of his total income—a significant drop from 2019. Of his total savings in 2020, 60% was saved in the SACCO and 40% through lending, which is roughly similar to that of 2019.

Image 7

The graph above (Image 7) highlights that John could not save at all for five months in 2020. As his income fell, John withdrew his savings from MOBAN (Image 8) and started saving more at home; however, his rate of saving reduced inevitably, with a greater temptation to spend the money on hand. John’s other savings tool, lending was also no longer feasible as creditors themselves struggled economically and started to default.

Image 8

John’s last hope to save his shop was to make a profit. He could use that money to support his household needs and buy more stock to sustain the shop. However, around May, 2020, the Government of Uganda asked fast-food businesses to not charge customers an inflated price to support the fight against the countrywide breakout of famine. This led to the fall of John’s business, who had finally sourced and bought a large consignment of stock for his business (see image 6 from week 44, that is, July, 2020) at relatively high prices.

John had hoped to make more profit, particularly due to the higher prevailing prices. When the government imposed lower prices, John could no longer sell his stock without making losses. He was forced to use the goods in the shop to feed his family and soon realized that he could not afford to run this business anymore.

Two factors forced John to close his business. Firstly, the decreasing profit from the business due to a shortage of stock in the market resulted in higher prices of stock. Secondly, the government’s directive that imposed lower sales prices. John diverted all the remaining reserves from his shop to a new venture of rearing livestock. And with that, Bushera Soft Drinks was no more.

What could have saved the shop from closing down?

John’s story demonstrates how precarious supply chains are, and how vulnerable small retail businesses are to price fluctuations, both in the prices of stock and the prices for sales.

Regulating the market price of commodities in times of emergency is critical to maintaining a healthy business ecosystem. However, the regulation must include both retailers and their suppliers to ensure that all parties maintain price. Secondly, all businesses–those who were operational and those who were not–needed support as the pandemic disrupted the buying patterns and reduced demand significantly. For others like John to survive, measures like direct cash transfers and credit guarantee for small businesses and loan moratoriums for longer periods could help.

We could unravel this rather complicated story with the help of detailed data from John’s financial diaries. This story and others in the Corner Shop project provide insights that can inform policy of the complexity and fragility of small retail firms in the poorest corners of the world.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs)- Kenya report (round 3)

Across the country, MSMEs were showing signs of recovery once the markets reopened. Yet they are nowhere near their pre-pandemic figures. Entrepreneurs are increasingly concerned about the increased cost of supplies and transportation, and struggle to secure loans. Customers too have limited their spending to essential goods. Read on as we examine the damage done and look at ways in which the government and other private agencies can help the sector recover. Key findings from the third round of a dipstick research funded jointly by MSC and SCBF feed into this report.

Corner shop diaries: A multi-country year-long research project on micro-businesses